| |

"I think the best thing that can happen with a movie, is it creates debate around a subject. I don't believe movies can change society, fortunately, and I hope not human beings. People must see the movies, read the books and then decide for themselves." |

| |

Director Costa-Gavras* |

Missing is the story of the disappearance of an American journalist in Chile in the early seventies who made the mistake of harbouring left wing sympathies while General Pinochet's far right military coup took over the country and terrorised the populace. Thousands were tortured and killed on the orders of a man who cosied up to our own Margaret Thatcher years later by supporting her Falklands campaign and giving her the impression that his principles were sound after years of human rights violations and the mass slaughter of political opponents. The best light I can shine on this odious pairing is that Thatcher supported the ends if not the means of Pinochet's intervention in Chile and chose to sweep under the carpet his reign of terror in order to admire what Chile eventually became under his rule. Really. That's a big sweep and in no way clean. Thatcher's admiration for the man continued even after he was arrested in 1998 for war crimes. An ex-Tory Policy Advisor said in 2006 that the reign of terror and murders had been overplayed and quoted the steep drop of the inflation rate under Pinochet's rule as proof of the man's worth. Simon Gardner in the Independent countered with "Well he might have brutally tortured and murdered thousands of people, but he had a great grip on economics! It could almost be a mantra for much of the political discourse of the 20th century."

Crucially, what director and co-writer Costa-Gavras does is almost completely avoid identifying the country, the situation and the man responsible and stays with the personal, the effects of Charlie Horman's disappearance on his nearest and dearest. He lets audiences come into this ravaged world and figure things out for themselves. Only the mention of a few Chilean cities identifies the beleaguered country. The events are listed as true (as spoken by Jack Lemmon in the introduction) and it's a testament to the film that the survivors of the extermination of the left wing sympathisers in Chile felt that the film was fair and effective. The fact this superlative work still lives well beyond its relevant time period is a great pat on the back for all those involved. Based on the book by Thomas Hauser, the original title of which I cannot give away without spoilers, was changed to Missing to partner itself with the movie.

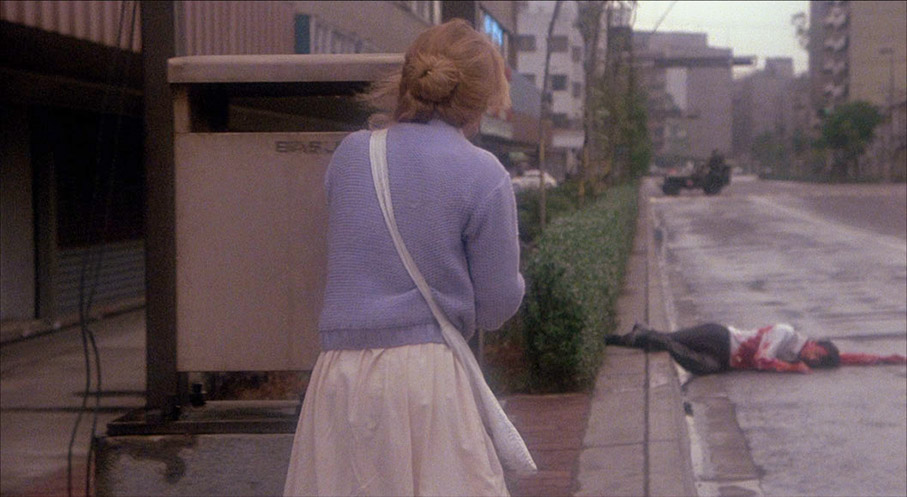

We get to know Charlie a little before his disappearance as he and his friend Terry navigate the streets with a curfew soon descending. A captain in the American Navy gives Charlie and Terry a lift but Charlie doesn't trust him enough to reveal his home address so opts to take a further ride once dropped off. In something of a mild panic, the two are denied taxis and have to stay at an expensive hotel with no way of contacting Charlie's wife Beth. With very few scenes played out, we know the political situation (pretty dire), the liberal outlook of Charlie and his friends, how dangerous it may be to keep a written record of any activity and the fact that Charlie's own countrymen may have something to do with the upheaval. This is a dangerous place where death is something death should never be; casual. The militia run riot at night as if they have been granted ownership of the crepuscular world and the right to unchecked violence and harassment. There is a remarkable pair of shots that shows a white horse (an animal that screams metaphor) throwing up sparks as it gallops wildly through the streets, almost stumbling at one point and after a cut, an Army jeep with gun-firing, testosterone filled men travelling right behind it. Editing is a powerful tool in the filmmaker's arsenal. Had it been one shot, the cruelty to the animal couldn't be reasonably sanctioned. But the cut allows Costa-Gavras one sublime visual in a film that resonates strongly with the terror of violence and its heavy threat at every corner.

There doesn't seem to be a single genre in which films like Missing, Schindler's List, Apocalypse Now!, Under Fire and Salvador could all comfortably belong but each has one terrifying aspect in common. With no screenwriting gurus extolling the predictable three-act structure at us, the singular context of all five of these films means that death can happen in a heartbeat to any one at any time. It is a daily, hourly even, harsh and horrific reality and as a way of unnerving an audience, it's a belter. Missing is abruptly punctuated mid-scenes with close, automatic gunfire and the actors convincingly flinch every time (I suspect the sounds were played in-scene. You can't 'act' a flinch from a nearby gunshot). It's a masterful way of reminding us of the constant threat and how decency and fairness might be rewarded. In a moment of extreme stress, Charlie's father Ed loses it only to be calmed down by two women who understand the situation and are not going to give a trigger-happy goon permission to kill them. They have enough permission already. In this country, you can die for doing the right thing because some power-crazed fascist bastard requires that opposing views to his own are silenced by torture and bullets. There is a moment in the film where I think I heard a familiar term for the first time... a phrase that became its own cliché awfully fast. Terry says to Charlie, "Be careful." He replies "Don't worry, they can't hurt us. We're Americans!" John Shea actually says "Amuricans!" which makes me think it was a cliché even then. How did Americans of a certain era convince themselves that they were immune to the abrasive nature of the world? Technically, historically speaking in film timeline terms, it was first used by Marion in Raiders of the Lost Ark... "You can't do this to me! I'm an American!" as that movie was based in 1936... I'm sure there are many other examples.

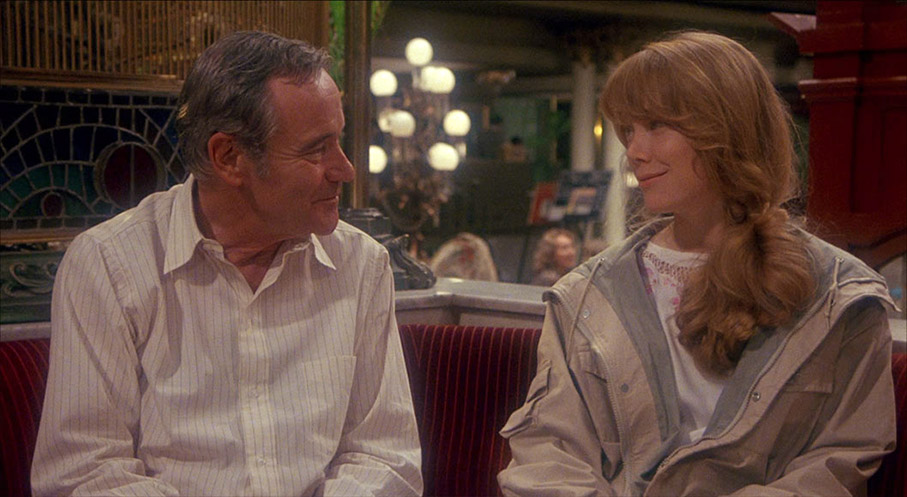

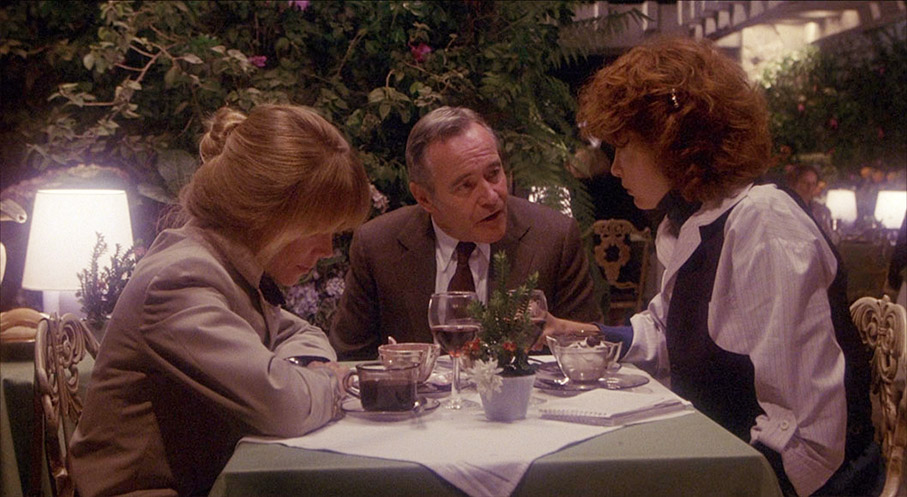

Regulars to this site know how much I admire and appreciate Sally Hawkins. Well, if there is an American equivalent, it's Sissy Spacek. In Missing, her character Beth, Charlie's wife, is vulnerable but strong. Here is a woman whose husband has been taken, perhaps a victim of the worst excesses of far right ideology but she fights to put right what's in her power to do so. Spacek is mesmerising. She's always in the moment, utterly convincing and her Texan accent, something from the male of the species I usually associate with swagger and bravado, comes across as the sound of gentle, loving, feminine sanity in this cauldron of chaos. Spacek can slay you with a look (as she did in The Straight Story) and complements her co-star in such truthful and beautiful ways. The real Edward Horman, who arrives in Chile to find his son, was a staunch Republican and proud of his nation. Subtly and superbly played by Jack Lemmon, who was still navigating out of the comedy straitjacket Hollywood had invited him to slip on, his character perhaps goes on the longest journey in the movie. He has to start testy and judgemental but in time realises that he shares so much more with his son than he previously believed and that Charlie was no gadfly journo mincing in front the sights of a machine gun. He was a decent human being who was probably guilty of no more than trying to stop a thug bundling a man and woman into a car. It was enough of a move to mark him. Lemmon then has to deal with the sharpest and most toxic human emotion, the one that eventually kills you; hope. This isn't the hope of Obama, audacity and all. This is the hope that keeps a loved one alive. Lost in what he has just learned late in the film, Lemmon descends a staircase and utterly inside his own mind, he just starts climbing the one in front of him. This is a broken man and Lemmon's subtlety is a joy. The double act of Lemmon and Spacek is the spine of the film and they make you go through every emotion.

John Shea plays the idealistic Charlie with a real twinkle in his eye. It's never explained why Beth and Charlie are in Chile (the real 'Beth', Joyce Horman explains this is her own extra) but given what happened it almost seems like the worst of bad luck. Pinochet deposed socialist president Allende after decades of democratic stability. It seems that Allende had presided over a fair, balanced socialist society (wow), one which Charlie and Beth were keen to see first hand. They were subsequently engulfed in the coup. Charlie's platonic female friend Terry is played by Melanie Mayron, an actress I loved in Girlfriends (Stanley Kubrick's favourite movie of 1979, just FYI and a film I must review at some point) and one whose work after Missing was mostly on US TV. The cinema misses her profoundly. Those seasoned actors playing the dissembling American power elite are all too credible and the man who gives the two friends a lift, Charles Cioffi as Capt. Ray Tower, ends up in the sexual predator role, drunk and gate-crashing Sissy Spacek's bath time. It's perfectly creepy in a film with threat in its very DNA. The fact that Spacek and Mayron can both laugh at the man's sloshed menace is quite the surprise. Keep that door locked, ladies. The Hormans' friends, winningly played by Joe Regalbuto as the brash Frank and John Doolittle as the more frightened David serve their dramatic purpose horribly well. I'll say no more.

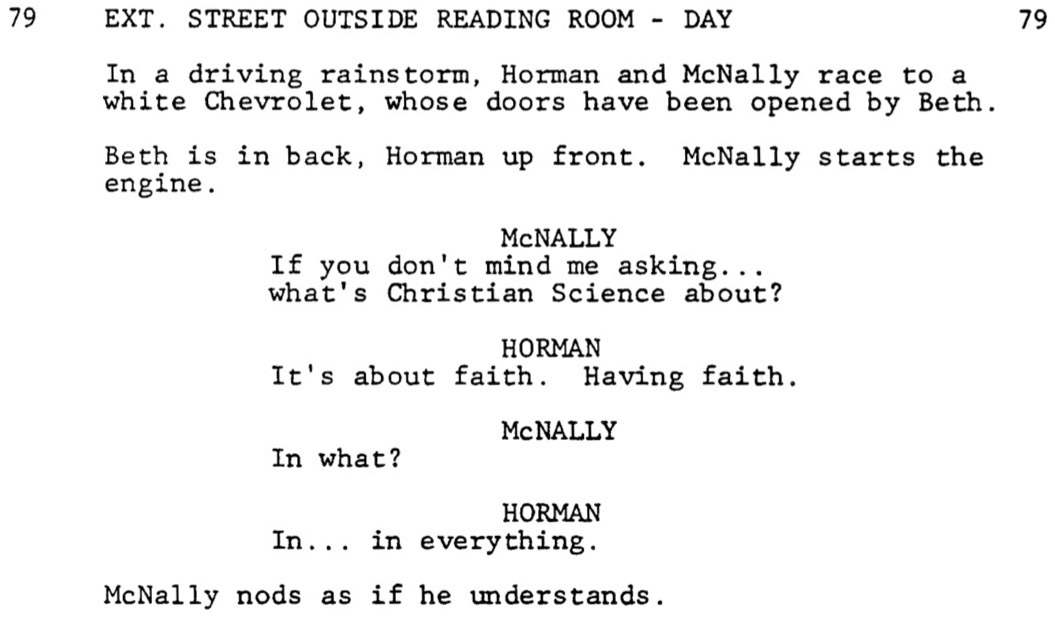

There is a moment when Ed Horman is questioned about his religious faith. We learn early on that he's a Christian Scientist, a prime oxymoron to be sure but a real religion nonetheless. Here's the original screenplay with dialogue as delivered by the cast.

In the most technically clumsy part of the film, Lemmon's words "in everything," is over dubbed with "in truth." It's clearly recorded after the fact and in no way matches Lemmon's mouth movements. I'd love to know why. I mean 'truth' is miles more specific than the woolly 'everything' but I'm still curious.

Let's identify the elephant in the room that has often cropped up in criticism of this movie (I recall the argument from reviews at the time of its release). At first reading it may seem like a fair argument, a question of addressing an imbalance. It is this; why should we care about the fate of a single American when thousands of radicals and critics were killed not to mention the tens of thousands tortured and imprisoned. The glib answer of course is that the film was funded by Universal (American) and Polygram Filmed Entertainment (British at the time) and would balk at trying the cover the whole story in a single film. Movies do this all the time, focus world events through a handful of characters. It's enough that this nasty piece of political history was put in front of a lens in the first place. If you care about the missing husband's family and how they suffered then perhaps you can magnify your concern to embrace the many more who suffered similar fates. Not to bring down the conversation with a pop culture quote but after Mr. Spock 'felt' the deaths of hundreds of Vulcans telepathically. McCoy is disbelieving and misquotes Scripture. "Suffer the death of thy neighbour, eh Spock?" The Vulcan's cool reply says it all. "It would have rendered your history a little less bloody." It didn't get much bloodier than Chile in 1973.

Finally there is the film's composer at the height of his creative powers. To give him his full name, Evángelos Odysséas Papathanassíou, also known as the less unwieldy 'Vangelis', this man was creatively on fire in the early 80s. His score that same year for Blade Runner will pass into film music history as a serious benchmark. There are very few cues in Missing but the love theme is teased early on but in full, it accompanies Jack Lemmon and Sissy Spacek down a airport corridor at the end of the movie, a shot that incidentally features a very subtle zoom/track which distorts the frame. When the cue's bass line heaves into full force as the end credits start, it almost has me hurling tears from my eye ducts. His love theme for this film is one of the most emotional and potent tunes ever written for the moving image and I do not care that the instrumentation is electronic. All I care about is the emotional connection. It pains me to say that advertisers may have diluted its power over the years but for me, it's still Vangelis at his very best.

Missing is a film that reminds us what happens when dark men poison enlightened societies so is more relevant today than it may have been in 1982... But as a superbly acted political drama, it's also well worth your time.

The 1.85:1 picture looks good with celluloid's inherently pleasing softness. Grain isn't an issue (if you really want to find it, it's there) and contrast levels are solid. There are no cinematographic bells or whistles and every shot is artfully lit as natural as filmed reality can be. Camera movement is organic to the actors and never calls attention to itself.

Missing was made five years after Star Wars introduced Dolby Stereo but I guess its talkative nature was well served with a simple mono soundtrack. Again, no fuss just a perfectly pitched soundtrack with those explosive gunfire bursts enough to make you jump along with the characters.

There are English subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing.

Audio commentary with actor John Shea and critic Jim Hemphill

This extra has been listed on most of the review sites but alas, it is 'ahem,' missing.

Guardian Interview with Costa-Gavras moderated by Derek Malcolm, 1984 (1 hr 24' 58")

This plays under the movie as a 2nd audio track. Costa-Gavras confirms himself as a Greek by birth but at 18 he moved to Paris taking advantage of the rich French film tradition. As with most life stories, luck plays its part. There are a few moments of humour that I didn't catch, a double-whammy of a Greek-French accent speaking English and the bass heavy condition of an old recording. The director gives a detailed explanation of his involvement with Missing. Politics comes up (duh) and Costa-Gavras refuses to be politically categorised making a great point about the shifts in the meaning of the word 'socialist'. The audience Q & A is a little frustrating despite Malcolm's attempts at repeating the question asked off-mic. The general muffled quality of the recording really requires some concentration. The director notes that five-year-old children in the US have marked Native Americans as bad people via exposure to westerns on TV – all movies are political. Costa-Gavras gets lively and full-blooded once asked why the murderer in Z was gay and so he should. It was an historical fact, one no honest filmmaker could steer away from. He is asked about his own movie tastes and among the list of directors and titles he reels off, I swear one was "Ford's Graps of Wraith (sic)," an interesting pronunciation of Grapes of Wrath! This is a solid and instructive extra despite some technical issues.

The Guardian Interview with Jack Lemmon and Jonathan Miller (1986): archival audio recording of an interview conducted at London's National Film Theatre (1 hr 55' 50")

This interview also plays under the movie on the third audio track. Jonathan Miller (one of my heroes incidentally) is clearly enamoured of the 'myth' that is Jack Lemmon. It was an odd choice of word. I would have used 'legend'. The recording quality is miles better than the Costa-Gavras one (with a caveat, see later). Lemmon is charming as ever and starts his interview with the delightful story of how he fell in love with being a comic actor. Subjects touched upon are method acting, relying on co-actors to round out your own performance, playing a woman (and how to walk like one) and how actors really need to be fearless in their pursuit of character. On Missing, Lemmon found that his hat 'contained' him and was never without it during the shoot. Inevitably Marilyn Monroe comes up and the absolute compliance to the written word working with Billy Wilder.

At about 8 minutes past the hour, you get a sense that Lemmon's voice is battling to be heard against another's – his own. I think this is what's known as 'bleed', the quarter inch tape suffering from age that causes other parts of the tape to 'rub off' or bleed into the primary audio. It's hard gong for a little while but the Lemmon answers are well worth persevering for. It's actually quite impossible to make out any words at about 13 minutes past the hour. Lemmon denounces one critic as psychotic – I believe he was talking about John Simon. We're not able to make out what's being said again at 1 hour, 22' 56" with more bleed and you really can't make anything out until 1 hour 31' 25" but even then the punch line of the Walter Matthau story is hard to discern. The final 24 minutes is clear with stories about his theatrical work, and his regrets not taking on a Shakespearean role.

Archival interviews with director Costa-Gavras (37' 33" in total and each in French with optional English subtitles)

Cannes Film Festival (3' 08"): In 1982, Missing was well received at Cannes. Jack Lemmon got the main acting gong and the film won the Palm D'Or. In this short interview on La Croisette, Costa-Gavras is asked about the white horse and his earlier work as well as the conflict between the Americans who funded the project, a film which then criticises American involvement in foreign politics.

Journal Antenne 2 Intv. (3' 28"): Shot in 1982 on the publicity trail, in a news TV studio environment, the director talks about how the film is an American one and how much support it received from American senators.

Many Americas (30' 57"): Recorded in 2006, this is a more reflective interview covering the entire filmmaking process with loads of great titbits of information on the production. My favourite was the director's idea that Ed Asner, who was very keen to play Ed Horman, would not be convincing in one particular scene when hurt vulnerability was needed, something Lemmon does expertly. Costa-Gavras says that Ed Asner would just punch the guy who insulted his son! Perhaps he had a point. The other gem is what gave rise to the title of this extra, Costa-Gavras' observation that there are many Americas. These days it seems like there are only two...

Freedom of Information – Joyce Horman on her experiences and the movie's shelf life (27' 19")

Also recorded in 2006 for the French DVD release, this is a cracking interview. Joyce Horman is Charlie's wife as played by Sissy Spacek and it's a delight to hear the real person behind the events. Working with Costa-Gavras became a great experience, a director sensitive enough to listen to advice from those that lived through the coup but tough enough to present this story emotionally and truthfully in as much as a two hour movie can achieve this. Joyce's story about the real Ed Horman meeting Lemmon is priceless and I also got a kick out of seeing the autographed photos from the cast. You got a sense that the actors were also politically engaged with this story. Joyce was invited to Cannes to bask in the success of the story of her life but it's also important to understand that Joyce didn't stop her political involvement and it's still official that the US had nothing to do with the coup in Chile. This was recorded before Pinochet died and it's clear that Joyce still had the dictator in her own sights. George W. Bush was president at the time of the interview so the abusive treatment of Iraqi prisoners is still reverberating around the world, something Joyce refers to. I would very much welcome her thoughts on the current administration... She describes the Truth Project, an event in New York that celebrated the film in 2002. I know of very few films that could be celebrated this way and it warms me just thinking about it. It's a win for decency and in this world at this time, that's a big win.

Politically Personal - Keith Gordon on 'Missing' (2018): a new filmed appreciation by the filmmaker and actor (24' 11")

Gordon is vivid in my mind for a series of youthful acting roles but his career blossomed as a director of quality TV. He's instantly recognisable as a 57 year old and has come a long way from Jaws 2. His enthusiasm for the film mirrors my own. An insight worth repeating is that Missing appealed to those people without any real political interest and spoke emotionally to audiences. That they would leave the cinema accidentally more enlightened about what their own country got up to outside of its borders was something of a plus. Gordon champions Lemmon's performance asking us to look at his eyes when he's merely a passive observer. It takes Lemmon's work to a new level. Gordon believes Missing gave birth to the term 'docu-drama' and therefore was protected against certain legal action. I'll end my appreciation of this extra with Gordon's own last words, which are spot on from my perspective... "Movies make you think and when you think, your politics evolve because you consider things from new angles and that's an important part of being a human being..." High five.

Original theatrical trailer (2' 56")

I'm sold... Using Vangelis' pulsing danger cue, this trailer hits almost every story beat and gives you almost the whole film in a perfect miniature (not that you would know that going in). Please note that my comment is not that 'they put too much in the trailer' but that what they did include is a supremely accurate indication of what the film holds in store. It's also classy with no voice of God just well chosen clips cut together with some sensitivity.

Image gallery: promotional photography and publicity material

This includes four black and white stills, eighteen colour and four poster examples with the Polish one being the most striking; a surrealist depiction of the mark of a corpse with an 'X' for a face and blood spots where the bullets went in. It is striking in the way that the US posters were certainly not.

Limited edition exclusive booklet with a new essay by Michael Pattison, an overview of contemporary critical responses and historic articles on the film

Pattison's piece is a thoughtful and sensitive defence of a film that had to walk on eggs in terms of what it said, alluded to and implied. He ends the essay with the Lemmon staircase moment I spoke about earlier. I swear, I always read the booklets last because I want to get my own thoughts down first. But then certain ideas are always going to coincide and the staircase moment is a notable one. Then there is a 1982 interview with Costa-Gavras in which he praises a writer's work (John Nichols) but was furious at not being able to credit him in any capacity because of the rules of credit arbitration. It's also heartening to find that Universal supported their director one hundred per cent... The Missing Dossier: An Interview with Thomas Hauser is a treat seeing things from the original writer's perspective. Then there is The New York Times' foreign correspondent Flora Lewis who took exception to the 'inaccuracies and speculation', all of which could have been cleared up if she had read the book according to the author. Taking parts of other articles on the film, this piece sums up the most contentious issues and edits them together.

Finally, apart from knowing that all the tanks in the film were made of wood, something else shocked me that I did not know at the time of my first viewing in 1982, nor could I have known mostly because the technology wasn't in place. But there is a spoiler listed at the end of this page that staggered me when I read it a few hours ago.

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0084335/trivia

Please see the film first. It's a small detail but enormously poignant.

This is a superbly but quietly directed, highly charged political film that shines its spotlight on the ugliest and most despicable treatment that the far right can dish out in pursuit of power. Lemmon and Spacek are mesmerising as their hopes grind them down searching for Charlie. The threat hangs over the movie like fog and there are scenes of undeniable visual power that make you ask the same question over and over. Why do people do these things they do? Or is it more pertinent, given human nature, to ask why most of us don't? Missing is an accessible film about heartache and loss which also packs a hard political punch. Highly recommended.

|