|

– PART 1 –

| |

"If I speak in the tongues of mortals and of angels but do not have love, I am but a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal" |

| |

St Paul to the Corinthians, 1.13 |

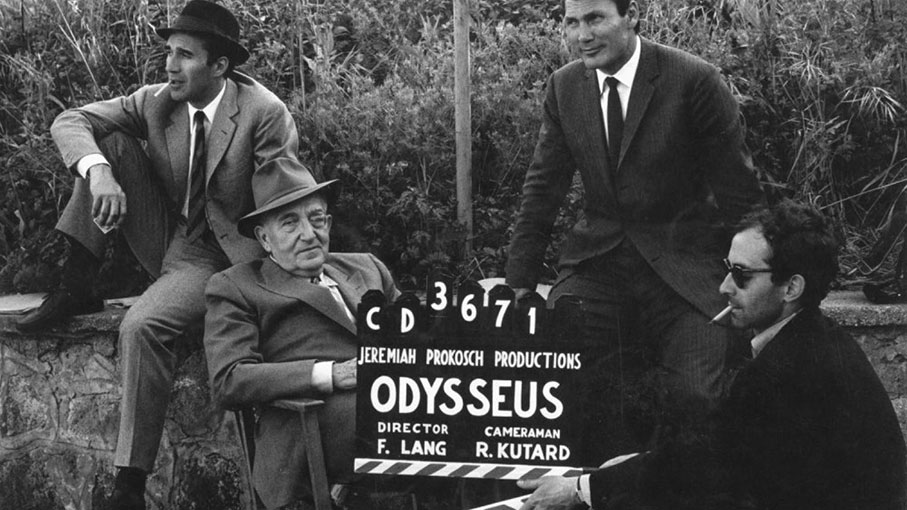

Martin Scorsese rightly describes Le Mépris [Contempt] as 'one of the greatest films ever made about the actual process of film-making.' Writing in Sight & Sound, film producer and scholar Colin McCabe, scorning qualifying adverbs, declared it to be 'the greatest work of art produced in post-war Europe.' Scoff, snort, splutter and disagree with that claim though we might, few who love cinema dispute that Godard was a towering colossus of the seventh art. Fewer still, even among the late director's detractors, would baulk at describing Le Mépris as an imperishable modernist classic. Despite its high-minded riffs on classical mythology and its Brechtian disruption of the conventions of narrative cinema, it is also widely regarded as the most accessible, exquisitely beautiful and emotionally charged of all Godard's films.

Shot in widescreen colour CinemaScope, it is certainly of his most opulent and lustrous. The film shimmers with revitalised luminosity in Studiocanal's 4K UHD multi-format re-release. This new 60th anniversary version represents the culmination of a restoration project begun in 2002 with the able assistance of the film's renowned cinematographer, Raoul Coutard. It dovetails with screenings of the film at BFI Southbank and coincides with 'Michel Piccoli: A Fearless Talent' – the BFI's ongoing retrospective devoted to the man described by season curator Geoff Andrew as 'one of the finest actors of modern times.' Piccoli was never more sure-footed than in his pitch-perfect performance in Le Mépris.

Studiocanal's painstaking restoration work eradicated all physical flaws but appears with the customary warning that the film 'contains historic attitudes that audiences may find outdated and offensive.' An essential feminist re-evaluation of the film's reputation; conducted alongside a wider re-assessment of Godard's inevitably outdated sexual politics; may have dulled the film's lustre slightly lately but, despite that, and despite being made in 1963 and firmly anchored in the sixties, Le Mépris looks, as fresh today as it ever did. It seems astonishing, indeed, that it was temporally wedged, within Godard's astonishingly fecund and prolific career, between Les Carabiniers, in which over-duped greys echo newsreel footage, and the slight, if skippy monochrome delights of Band à part – both of which feel like grainy films of the fifties in comparison. Le Mépris emerges from between those films in a dazzling display of ravishing primary colours, all incandescent blues, reds and yellows. Godard had earlier used colour effectively in Une femme et une femme and would do again to stunning effect in his later video films, but nowhere in his work does it shimmer as vibrantly as it does here.

So much has been said for and against the film by so many of Godard's admirers and detractors; by so many academics, critics, directors, historians and theorists; that it would be difficult, anyway, to speak of it now, even if Godard's reputation weren't, thankfully, being set right by feminists and, regrettably, eviscerated by assorted reactionaries in lock-step with our reactionary times. It may now be impossible to say anything original about Le Mépris, but I'm more than happy to recycle preceding readings. After all, Godard's collagist work owes as much to William Burrough's cut-up, copy-and-paste techniques as to Eisenstein's theories of the montage of attractions. Although it is superficially the story of a film being made and marriage unravelling, the film's extraordinary complexity, fortunately, ensures that there remains ample room both for observations on earlier observations about it and comment on the claims and counter-claims associated with recent re-evaluations.

Films made over half a century ago will wilt, they'll certainly fade fatally if not restored, but this salutary tale of integrity under duress speaks to our scoundrel times as if from the future. Although I'll touch on certain questions raised by feminists about the film to set it in context, I have no intention of wading in to defend Godard on charges of misogyny. That would require another piece of its own. Rather, I'll take a leaf out of my former tutor Laura Mulvey's book and focus, as she does in Afterimages: On Cinema, Women and Changing Times, on how Le Mépris reflects shifts in the balance of power between European cinema and Hollywood. I'll also celebrate Godard's penchant for quotation, as she does both in that same essay and in her contribution to the London Consortium's Collection on Le Mépris (which she co-edited with Colin McCabe). 'A fabric of quotations', literary quotes, philosophical quotes, quotes on screens, quotes within screens, people as quotes, etc). Primarily, though I'll collate certain details of Godard's personal life that ricochet off and draw out those themes and look at the film's locations. Finally, I'll heed the advice Godard offered in Passion: 'Once in a while, take advantage of the fact the sentence isn't finished to begin speaking and begin living.'

Laura Mulvey, of course, is best known for coining the imperishable phrase 'the male gaze' in her 1975 essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema – which arose from her involvement in the Women's Liberation Movement and was created at a time when John Berger's 1972 Ways of Seeing series continued to inform ideological discourse, particularly around misogyny, the production of images, commercial propaganda and political power. In her more recent film-essay Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power, Nina Menkes speaks to Mulvey about her essay before fanning out to consider the ways the camera-eye has historically objectified women, the implications that has for employment discrimination in Hollywood, and how it feeds into the rape culture highlighted by the #MeToo movement and the tip-of-a-shitheap behaviour of men like Roger Ailes, Andrew Tate and Harvey Weinstein. Menkes makes no mention of John Berger, elides Mulvey's profound psychological insights into scopophilia, and merely hints at the ways pornography has saturated and deformed our culture, but she, like Mulvey and Berger, provide grist for generations of scholars. Attempting to unpack that morass of progressive thought in a review of Le Mépris would be idiotic in the extreme, so a different tack seems sensible.

Setting aside Godard's characteristically combative pronouncement that 'the text is death, images life', with its implicit suggestion that only audio-visual essays like Koganda's or Godard's own would be up to the task of tackling his work, I approach this review with trepidation – partly because I'd scratched the itch to write about Godard in academia and in a piece about Vivre sa vie on this site, but primarily because the unsettling sense of loss I felt after Godard's death by assisted suicide, less than a year ago, still gnaws. And then there is the sheer range and reach of Godard's work and the fact that I am currently labouring under 'long covid'. I apologise, in advance, if I occasionally come across slightly scatter-brained but offer no apologies if I fail in the ensuing attempt to do the film and Godard justice. Who, after all, could? As Colin McCabe also said, 20 years ago, in his invaluable survey Godard: A Portrait of the Artist at 70: 'It would be a fool who thought they had all the necessary competencies to comment fully on [Godard's] extraordinarily rich oeuvre, which is constitutively allusive.'

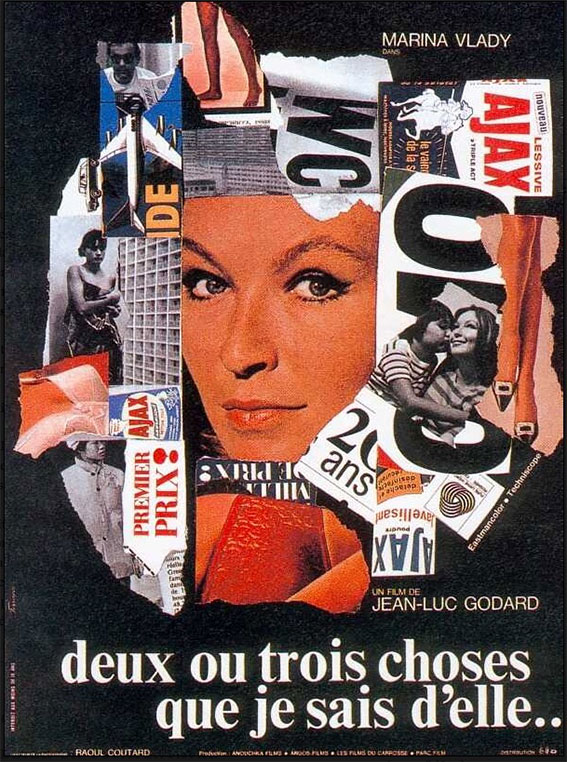

Let's keep it personal then; eschew the words 'legendary', 'seminal' and 'iconic'; and see where we go from there. Like many a frisky young cinephile, I was initially drawn to Godard as much by his anarchic energy and impish humour as by the cinematic brio and bravura invention of his early films. Like many others, I was smitten the moment I first saw À bout de souffle and I remain amazed to this day that Godard had the audacity and stamina to shoot Made in the U.S.A. and Deux ou trois choses que je sais d'elle simultaneously – the former in the morning, the latter in the evening. Soon, though – as I immersed myself in the radical cinema of directors such as Eduardo Coutinho, Thomas Harlan, Chris Marker, Pere Portabella and Yvonne Rainer – I came to prefer the insurrectionary irreverence and subversive of Godard's militant phase, his refusal of restraints and contrarian fury. Godard's argumentative tenacity recalled a comment by the Republican MP Henry Marten about his contemporary 'Freeborn John' Lilburne: 'If the world was emptied of all but John Lilburne, Lilburne would argue with John and John with Lilburne.' I was grateful Godard had crossed to the Left.

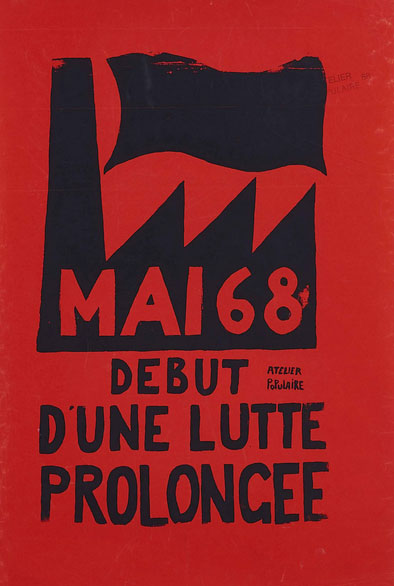

In his recently released book Fassbinder Thousands of Mirrors, Ian Penman described the mighty German maverick as 'an amalgam of Bertolt Brecht, Joe Orton, Daniel Cohn-Bendit, Sid Vicious and Orson Welles'. If we substitute John Lydon for Vicious and John Lilburne for Orton, and then layer in Roberto Rossellini and Walter Benjamin, the description fits Godard perfectly. Godard and Fassbinder responded in different ways to the modernist dilemma described by Robin Wood in his 1969 essay on Weekend (which he calls, 'the most frightening, exciting and challenging film I have ever seen): 'the tendency of works that honestly reflect a fragmentary and disintegrated culture to become themselves fragmentary and disintegrated.' That dilemma was bound up with another, the attendant loss of audience – which Fassbinder addressed by working in television and Godard faced head on by addressing the new audience for revolutionary cinema temporarily created by May '68.

Watching the Ciné-tracts and Vent d'est was a politicising experience akin to Tom Wolfe's of the party that generated his essay 'Radical Chic': 'A Black Panther field marshal rose up beside the north piano (there was also a south piano) in Leonard Bernstein's living room and outlined the Panther's Ten-Point Programme to a roomful of socialites and celebrities, who, giddy with nostalgie de la boue, entertained a vision of the future in which, after the revolution, there would no longer be any such thing as a two-story, thirteen-room apartment on Park Avenue, with twin grand pianos in the living room, for one family.' If my slightly condescending view of Godard's generation of radicals was, like Wolfe's, that they faced what was in front of them with vim and vigour and what they knew then, and we can't ask more of them than that. I also felt I understood the heart at war with the structure of society and what drew Godard, Gorin, and the Panthers to Maoism.

I always bristle and redden when self-righteous contemporaries with little or no knowledge of history (who often, indeed, have little interest in anything or anybody other than themselves) deride soixante huitards for their political naivety. Rich that, coming from those cannot see the connections between, say, the Long March and the 'long march through the institutions', the Vel' d'Hiv roundup and the massacre on Pont Saint Michel, Dien Bien Phu and Mai Lai, the Cinema Rex fire and the Tehran coup of 1953, and so on. This tendency to read history backwards, judge, and smugly assume they'd have known better and acted differently has led to asinine calls for Godard to be struck from the canon and the record.

Whatever mistakes he made personally and politically, whatever you think of Godard's militant phase, regardless of your politics, it remains, at the very least, an invaluable history lesson – to which I return occasionally whenever I find myself forgetting or feel myself softening. Finally, though, realising that the 'Long '68' was long gone and tired of revolutionary daydreams, I decided that late Godard was more interesting – particularly his video and television work with Anne-Marie Miéville after the strategic retreat to Rolle and his magisterial Histoire(s) du cinema. Then something odd happened, I recently returned to Godard's films of the sixties and fell in love with them all over again. As time goes by nostalgia for the things of our youth intensifies and I'm now ready to revisit Le Mépris. What follows below will almost certainly contain traces of the melancholia that pervades the film and is so exquisitely enshrined in 'Camille's Theme', Georges Delerue's haunting perfect accompaniment to Godard's elegiac cine-poem – a piece of music fully the equal of Maurice Jarres' 'Lara's Theme' score in Doctor Zhivago.

Adapted from Alberto Moravia's novel Il disprezzo (Contempt), Le Mépris was a multi-lingual international co-production avant la letter and Godard's first foray into big-budget industrial film-making. Those realities generated a cautionary tale of embattled integrity that portrayed the struggle between a director (Fritz Lang as Himself) and a producer (Jack Palance as Jerry Prokosch) as the clash between commerce and creativity. Film theorist Jacques Aumont described it as 'A giant J'accuse ... which portrays producers as dealers of death.' Godard opened up a can of worms when he secured the services of the film's star turn, Brigitte Bardot – the sex symbol of the era, the woman described by Jean Cocteau as 'the soul of our era' and by Simone de Beauvoir as the 'locomotive of women's history.' He pulled the coup off through his friendship with Bardot's partner, Sami Frey (who would appear in Bande à part), but it helped that he'd written glowingly about Bardot's performance in Et Dieu . . . créa la femme (And God Created Woman) as a neophyte critic on Cahiers du cinéma. It also helped that Bardot was keen to amend her image by borrowing some of Godard's cultural capital. We need not doubt she was also happy to be paid handsomely ('You've got the brains/I've got the looks/Let's make lots of money!'). Although Bardot inadvertently helped Godard persuade producers George de Beauregard, Joseph E. Levine and Carlo Ponti to pour over a million dollars into the project, her fee alone accounted for half the film's budget. A strong supporting cast, including Fritz Lang and Jack Palace swallowed up most of what remained.

Godard learned valuable practical lessons from his chastening encounter with Joe Levine and he would later raise a million dollars for his own film Tout va bien by persuading Jane Fonda and Yves Montand to appear in it. The fraught experience of working with producers left their mark though and further intensified Godard's yearning for freedom from outside intervention. While reviewing Cyril Schäublin's finely calibrated film Unrest last year, I'd been struck by the debt Godard may have owed to the fiercely independent artisan-Swiss-watchmakers of the Jura Federation, who plied their ancient trade near where Godard began and ended his life. Their self-managing artistry was underpinned, as was Godard's Sonimage work with Anne-Marie Miéville in Switzerland, by the essential skills of the petit commerçant – a term he has used to describe himeself since the Dziga Vertov Group folded. In Le Mépris, Paul Javel pointedly tells Prokosch that he wants 'to make films like Griffith and Chaplin. Like in the era of United Artists.' Godard's work could not have happened if he hadn't created the necessary conditions for it himself.

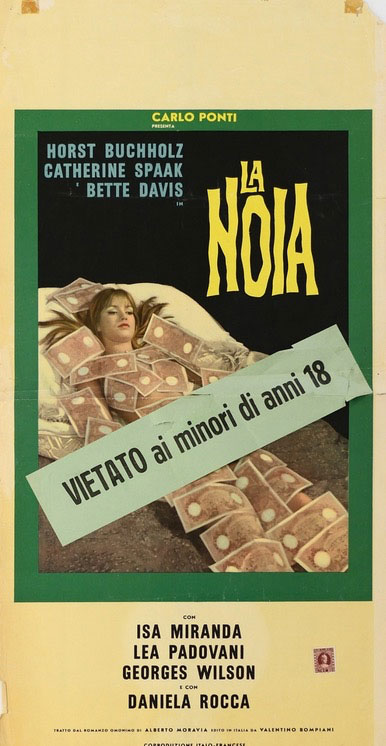

The inevitable problems surrounding the financing of the production are inscribed in the film. They meant that Godard had to improvise far more often than his hefty budget might suggest, indeed the film's riveting central section was created on the hoof to fill screen time. Levine's exploitative ethos and modus operandi is evident in his approach to La Noia [Boredom] – another Moravia adaptation, which Damiano Daminani was busy filming in Rome, with the backing of Ponti and Levine, while Godard was filming Le Mépris nearby. Levine had already secured his big-name stars, Bette Davis and Horst Buchholz, but only revealed his high hopes for French-born unknown Catherine Spaak after the event. While pushing La Noia, Levine told anyone who'd listen that Spaak would be 'the biggest new star of the 1960's. This girl will be the Bardot of her generation. Ten years from now there will be girls billing themselves as the new Catherine Spaak.' Bardot insisted that a body double be used for certain shots in Le Mépris and a cabaret dancer was paid six hundred francs to perform that function or those parts. Spaak had not such qualms or power and the literal 'money shot' in La Noia featured her naked on a bed – being covered with bank notes.

Speaking of money: Charles Bitsch, Godard's Assistant Director on Le Mépris, recalls asking Godard how much the crew should be paid for the re-shoots; pay them double what they ask for, Godard replied, 'If the producers want a supplement then they'll get it.' Revenge can be sweet, even if the producers (all men, of course) still hold the whip hand. Bardot plays Camille Javal, whose husband Paul (Michel Piccoli) is hired by a philistine predatory producer, Jeremiah Prokosch (Palance), to jazz up and sex up a film adaptation of Homer's The Odyssey. The director of this film-within-a-film is Fritz Lang, who plays himself as the embodiment of unimpeachable (European) integrity, the moral centre of the film, or, as Godard said, 'the conscience of the film, the moral hyphen that joins Ulysses's odyssey to that of Camille and Paul.'

Godard gleefully plays himself too as Lang's assistant and directs Raoul Coutard who – guess what? – also plays himself. Palance plays himself too, as always, but also, as money-hungry Prokosch, he effectively plays both Levine and Ponti. When Bardot dons a black bob wig, she plays herself as Anna Karina as Louis Brooks. When Piccoli dons a hat to play Dean Martin in Some Came Running, and again when he shudders at the thought of shoddy commercial compromise, he is playing Godard. What of it? Wasn't that always Godard's way? Didn't Jean-Paul Belmondo play Michel Poiccard playing Bogart in À Bout de souffle? The point is, as Peter Wollen says in Paris Hollywood, Godard never worked with scriptwriters and seldom gave actors traditional directions (to Palance's horror) so 'his films began to turn into documentaries about their actors.'

In a heartfelt lament for Godard published as 'Godard is Perhaps Dead' in Cahiers du cinéma, Scorsese names Le Mépris as his favourite of all Godard's films. He says: 'It is a genuinely tragic experience, a film about real betrayal: the betrayal of a wife by her husband, the betrayal of cinema (personified by Fritz Lang as himself—his spirit also haunts Jacques Rivette's Paris nous appartient/Paris Belongs to Us) by Jack Palance's producer, the betrayal of Homer, of myth, of antiquity. The final moment, when the camera pans away from the film being made to the calm ocean in the distance, over calls for silence, never fails to move me deeply. It's an elegy for cinema, for love, for honour, for Western Civilization itself.' Scorsese might have thrown Homer into his list of elegies for good measure and Godard himself, with a wink to Proust, said Le Mépris might have been called In Search of Homer. The film's references to classical mythology may leave contemporary audiences cold (the era of the liberal Arts & Humanities education having long since been succeeded by the vocational training of Business schools and Capitalist Realism), but the film's melancholic elegiac elegance and compacted mediation on the pathology of modern life continues to resonate.

| Commodified Nudity and The Male Gaze |

|

Essentially a triptych or, better say, a three-act tragedy, the film opens at the Cinecittà studios outside Rome. Godard immediately establishes a self-reflexive tone. As Godard reads the opening credits (pointedly acknowledging Beauregard and Ponti but leaving out Levine), Raoul Coutard's camera tracks forward, like the Lumière brothers' train at La Ciotat, before turning its gaze upon us. There follows the controversial prologue featuring Bardot naked, which was actually shot during the post-production process to pacify Levine and Ponti (or 'King Kong' and 'Mussolini' as Godard preferred to call them) who felt they'd paid up front for Bardot's behind and hadn't got what they paid for. The dynamics of the violent clash of competing values between Godard and Levine are evident in the scene in which Prokosch, as Levine, tells Lang that he hasn't given him what he paid for: 'You've cheated me Fritz, that's not what's in the script'. Godard made films with whatever was to hand.

Godard's use of female nudity has led to charges of exploitation, and commodification not unlike the charges levelled by him at the pimps of prostitution, the promoters of the beauty myth and other forms of sexual trafficking – which is to say, those who profit from exploiting women's bodies. Godard's tendency to represent the body in fractured terms makes him a suitable subject for Nina Menkes. As he does with Bardot in Le Mépris, he consistently deploys images to represent bodies as collections of separate part-objects rather than coherent wholes attached to complete human beings. In his book The Films of Jean-Luc Godard: Seeing the Invisible, David Serritt says, 'It is incontestable that Godard's rebellion again the commercial film establishment [missed] a beat or two when it comes to the subject of commodified nudity.' Is it? Did it?

In Ways of Seeing, John Berger delineated the way the Western Art tradition of the nude established the male gaze, the way it seeped into advertising, and then worked its way out into the wider culture. Godard and Bardot were embedded in that tradition and complicit in the nude shots, but those were their times and that was then. In the year of Le Mépris, nudity in the cinema was still comparatively rare and controversial, city centre cinemas still existed like that showed and billed Vivre sa vie as a sex romp. And let's not forget Philip Larkin's tongue-in-cheek claim that, '1963 was the year sexual intercourse began' (which, I confess, reminds me of a joke that amused me in boyhood: in Franc Roddam's Auf Widersehen, Pet, Jimmy Nail's Oz visits a German brothel and says to one of his colleagues: 'I tell ya mate, sex is in its infancy in Gateshead). Jonathan Miller suggested that 'England was stuck in the Thirties until the Sixties' but he didn't specify a year. Certainly, this was the shockingly repressed era of European films as serious art and soft porn, when critical attention to 'continental films' in magazines like Continental Review Magazine clothed sexist titillation in an intellectual cloak (as some say Godard did).

Once, while researching the wave of cinema closures in the 50s and 60s, I came across a story that chimes with that observation about the salacious connotation of the word 'continental' back then. The Woolwich Empire stopped showing films in the late 50s and turned to 'Nude Revues', like the one in Jacques Demy's Max Ophȕl's homage Lola and Godard's Une femme est une femme (Godard's first film in colour CinemaScope). In an attempt to reverse the downward trend in box office takings, The Empire cinema in South London advertised itself variously as 'London's New Girlie Theatre', 'The Windmill of Woolwich', and 'The Most Sexational Show in London.' Not even twelve dancers a day, working from twelve noon to twelve midnight could save the Empire, which closed in 1958. A long-standing barmaid at the theatre told the local paper: "Nudes. That's what killed the business. Who wants to take their children to see girls undressing?" Indeed.

This was the era of the Profumo affair and Lewis Morley's 'nude' image of Christine Keeler sitting astride a wooden chair. That image turned fifty just before John Schlesinger's harbinger of the Swinging Sixties Billy Liar. Taken in a studio above the Establishment Club in May 1963, Morley's image is saturated in ambivalence. The chair itself is 'a fake', a mass-market imitation of Arne Jacobsen's original design, and the image is equally compromised. Keeler was reluctant to be photographed naked and the chair was Morley's persuasive means of holding her to a contractual agreement to do so. Keeler's Bardoesque 'sex kitten' pose, then, is not the bold statement of sexual self-confidence it seems to be, and the chair behind which she sits is both a screen and a screen upon which double standards were projected. Julie Christie's performance in Billy Liar provides a more honest and potent symbol of the 'permissive society', just as Bardot's performance in Le Mépris does.

Godard's female leads are seldom objectified though, his nudes tend to turn their backs to the camera, and his images of women were often radically empowering – particularly after his partnership with Anne-Marie Miéville began. Take the sequence in the Numéro deux in which the grandmother (Rachel Stefanopoli) is shown conducting domestic chores or 'women's work' (c.f. Chantal Akerman's Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce). The stereotype is undercut by the accompanying voiceover – from embattled Germaine Greer's pioneering polemic The Female Eunuch. 'Women don't realise how much men hate them. She is punished as an object of hatred, fear and disgust . . .' As the voiceover continues, images of domestic labour are replaced with those of the elderly woman naked before a bathroom mirror. In Godard's film, commercial cinema's notions of visual pleasure and conventionally 'beautiful' bodies' are overturned. Rachel Stefanopoli's disrobing, like Emma Thompson's in Good Luck to You, Rio Grande, empowers. In both films, a woman's unembarrassed, self-confident exposure of her body challenges the mass-market commodity culture that rigidly excludes them in favour of conventional-conformist 'glamour'.

Godard interrogates the idea of the gaze at oneself or Self Gaze which suggests that visual pleasure can be found by distinguishing between two ways of seeing and by choosing the one most often overlooked. Again, as Rachel Stefanopoli washes herself, the voiceover proceeds with the grandmother's own reading from Greer, which might have been written, perhaps was written with Bardot and Le Mépris in mind: 'The sun only shines to gild her skin and hair; the wind blows only to whip up the colour of her cheeks; the sea strives to bath her; flowers die gladly so her skin may luxuriate in their essence. She is the crown of creation, the masterpiece (sic). The depths of the sea are ransacked for pearl and coral to deck her . . . baby seals are battered with staves, unborn lambs ripped from their mothers' wombs, millions of moles . . . and other small and lovely creatures die untimely deaths that she might have furs.'

If Godard flip-flops between critique of (North American) consumer capitalism and delighted fascination with it, critique of the Male Gaze and perpetuation of it, so do his images, but don't we all oscillate? We live within Capitalism but Capitalism lives within us and the fine line between contestation and complicity gets finer by the day. And anyway, as Peter Wollen pointed out, the dominance of politics, the male voice, and the 'master text' in Godard's work started to dissolve after the breakup of the Dziga Vertov Group was precipitated by his accident in 1971. 'A new tentativeness began to be felt.' Godard's moves from Paris to Grenoble and from there to Rolle marked the beginning of his domestic and artistic partnership with Anne-Marie Miéville and 'Godard now began to be interested in video as a populist form, as people are interested in the internet today. His view of politics had changed in the wake of feminism, and he now tried to explore the ways in which the 'personal' was intertwined with the 'political'.' Anne-Marie Miéville, having nursed Godard back to physical health over several years, simultaneously introduced healthier ideas into his life, and we should be forever grateful for that. Je vous salue, Anne-Marie!

It is often noted that Miéville merits more attention in her own right, but, like analysis of Godard's misogyny, that must wait as we must now return to Le Mépris and its prologue. Camille/Bardot lies naked (before us) while she invites her husband (and us) to approve her anatomy, bit by bit. Paul brings the scene to a close by reassuring Camille that he loves her 'totally, tenderly, tragically.' Just in case Paul's concluding adjective weren't enough to insinuate unease and hint at matrimonial trouble ahead, Godard drives the point home graphically at the start of the following scene, set back at Cinecittà, when Prokosch cuts between the couple in his red Alpha Romeo as they approach each other to embrace. Godard keeps us guessing what Camille's thoughts are when Prokosch crudely comes on to her, but the suggestion that Paul is, to all intents and purposes, pimping her to feather his nest. In both Vivre sa vie and Deux ou trois choses que je sais d'elle the processes of commodification integral to consumer capitalism are, as it were, laid bare: the young women played by Karina and Vlady must sell themselves as objects in order to afford other objects. They work for the industries of the day, clock off, and work for the industries of the night. In Vivre sa vie Godard uses prostitution as a metaphor for the dehumanization he increasingly associates with industrialized consumer society. In Le Mépris, too, money and sex, the profit motive and prostitution are inseparably interlinked, as so often in Godard's work.

In the central section of the film, we move indoors with the bickering Javals and find ourselves confined in their half-furnished flat and half-dead marriage for a coruscating (and cost-effective) half-hour sequence that testifies to the conspicuous talents of Bardot and Piccoli, the technical prowess of Coutard, and the preternatural gifts of Godard. We watch as the couple circle one another in an impeccably choreographed dance, part, and engage again. The film closes at Casa Malaparte, the architectural marvel on Capri's eastern seaboard, where the Javals' relationship deteriorates further, before buckling under the weight of their mutual incomprehension, Paul's indecision and indifference, and Camille's consequent contemp. Shooting on the film Fritz Lang will never make continues as Godard orders 'silence' on the set, Delerue's lush cadences trill one last time, and Coutard's camera sweeps out to sea – lingering over the boundless, timeless beauty of the Mediterranean and leaving us to contemplate the fragility of love and transience of human existence.

Lang's appearance in Le Mépris is significant and symbolic. He willingly agreed to appear in the film as he admired Godard, but only on the condition that he worked exclusively as an actor. In his book Fritz Lang in America, Peter Bogdanovich quotes Lang on Godard's style and contempt for Levine: 'Godard improvised a lot . . . I was very amused by one thing: he wrote in sequences and, let's say in sequence seven – after he'd told them what happened in terms of the whole story – he wrote, 'Now, dear producer, I couldn't tell you exactly how I'll shoot this scene or what will happen in it. How can I know, now, how the furniture will be in the room or how Brigitte Bardot will step into the bathtub? But, dear producer, after I've seen how Brigitte does this and this, I can tell you." I was very amused: three or four times "dear producer" and he never told them anything really. Much of the dialogue was improvised, but there was not one bit of it of which Godard did not approve.'

'The artist must always bite the hand that feeds' insisted Lindsay Anderson, 'must always aim beyond the limits of tolerance.' While Lang's anecdote reveals much about Godard's adversarial relations with Levine, it is also instructive as a reminder of his improvisatory style. Jean-Pierre Melville's argued that Godard's films were 'anything shot anyhow', but there was always cinematic method in his madness. Far too much has been made the presence of a script and schedule for Le Mépris. Godard did work from scripts, notably in his 'comeback' films of the 80s, but restless invention always outbid plodding planning for him. John Steinbeck said, 'Ideas are like rabbits. You get a couple, learn how to handle them, and pretty soon you have a dozen.' Godard had plenty.

Caroline Champetier, who worked with Godard on Détective and Hélas pour moi, bears out Lang's comments about Godard's meticulous but instinctive hands-on approach. In her Observer obituary of Godard, she stresses his all-consuming commitment to cinema, even revealing that while filming he began the day with an apple and seemed to survive on beer and omelettes. She says, 'I was struck by how physical Godard was. He attached so much value and importance to props, placing them carefully on the set. To me, he looked like a painter, overseeing the composition of a still life. I told him I thought he was a manual worker rather than an intellectual. He smiled. I think he liked that.' I bet he did. Georgia Moll, too, offers evidence of Godard's improvisatory style when she recalled how little direction he would give: JLG: 'You come down the stairs and you cry'. GM: 'Why do I cry?' JLG: 'I don't know'!

Godard lived and breathed cinema. He loved and lived it. His intense commitment to the medium combined with his wired-up energy to intensify the crackling tensions that often erupted on his sets and exacerbated his reputation as a difficult man to work with. 'A good artist should always be isolated,' said Orson Welles, 'If he isn't isolated something is wrong.' Although seldom cruel, generally diffident, surprisingly softly spoken, Godard had a talent for making the right enemies. He let nothing stand in his way. Woe betide anyone who came between him and his cinematic vision. Scores of those he worked with describe him as an intimidating presence. That may have been as much due to his cultural aura as his poor personal behaviour, but he was undoubtedly brusque, often rude in his dealing with others. His combative personality and outspoken views spared nobody. What of it? Sam Mendes is as charming as he is mediocre. As George Bernard Shaw said, reasonable people adapt to the world, unreasonable ones adapt the world to themselves, ergo progress depends upon the unreasonable ones.

PART 2 >>

|