|

It is, perhaps, a little ironic that the author of some of Japan's most widely known and respected collections of ghost stories is not Japanese at all. Born in Greece of Irish-Greek parentage, Lafcadio Hearn emigrated to America at the age of 19 and worked as a journalist in both Cincinnati and New Orleans. During this time he was sent to Japan as a correspondent and fell in love with the country, its art and its culture, and eventually moved there, married and raised a family. He continued to write on a variety of subjects, some of his most prominent work being the adaptation into prose of several supernaturally-based Japanese folklore tales. These were published as collections such as Shadowings (1900), Kottō: Being Japanese Curios, with Sundry Cobwebs (1902) and Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things (1903). 61 years after Hearn's death, Japanese director Kobayashi Masaki, aided by respected screenwriter Mizuki Yōko, set out to make a film of four stories adapted from the above three volumes. The result was Kwaidan (or Kaidan in Japanese, literally 'Ghost Story'), now rightly regarded as one of the most sublimely realised cinematic tales of the supernatural to emerge from, well, anywhere.

In the first story, The Black Hair, a poverty-stricken samurai divorces his loving and faithful wife and marries the daughter of the Governor of a distant province, in whose service he then finds work. But the marriage proves to be an unhappy one, and ten years later, when the Governor's official term of service is complete and the samurai is freed of his obligations, he returns to Kyōto in the hope reuniting with the woman he realises he was wrong to abandon and whom he has been dreaming of since, but when he arrives all is not what it at first seems.

In Woman of the Snow, old woodcutter Mosaku and his young apprentice Minokichi are caught in a snowstorm on their way home from the forest in which they harvest their wares. Cut off by a river, they take refuge in a broken-down hut, but in the night Minokichi is awakened by the arrival of a white-dressed woman who kills Mosaku with an icy breath. Feeling pity for Minokichi, she spares his life on the condition that he never reveals what happened this night to anyone, not even his most beloved. A year after, Minokichi meets a beautiful girl whom he takes for his wife, and one evening he watches her sew and is reminded of that fateful night...

Hoichi, the Earless tells the story of blind storyteller Hoichi, whose skilled biwa playing and emotive recital of the tale of the great sea battle of Dan-no-ura impresses a priest of the Amidaji temple. The poverty-stricken Hoichi is offered a home there, which he gladly accepts, being required only to occasionally perform his musical and storytelling skills in lieu of rent. Left alone in the temple one evening, he is visited by a samurai who serves a high-ranking lord. Hoichi's recital of the battle of Dan-no-ura has become renowned and he has been summoned to deliver the story to the court which the samurai serves. Hoichi's rendition so impresses the Lord that he is promised a large reward, but only on condition that he returns for the next six nights to repeat his performance and that he tell no-one of his visits. Hoichi is true to his word, but when the temple priests become curious about the nature of his night-time excursions, two of them are ordered to follow him, unaware of the pledge that Hoichi has made.

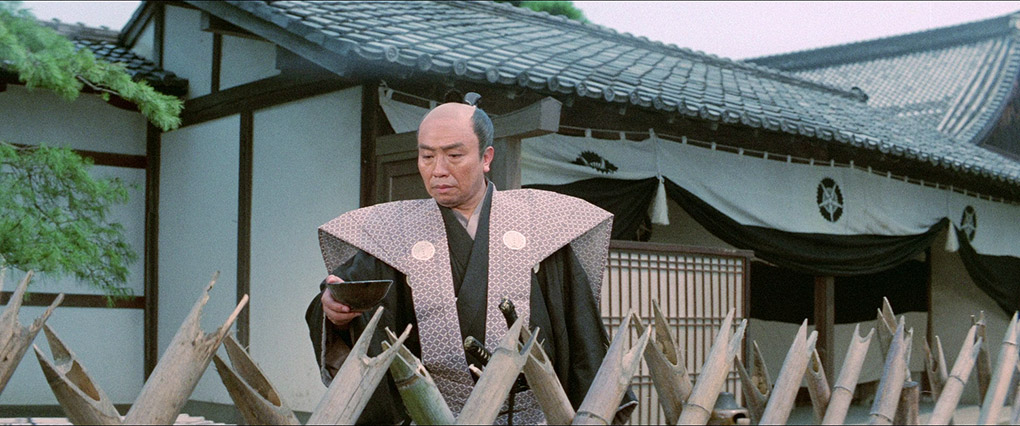

In the final story, In a Cup of Tea, the attendant of a lord who is resting at a tea house fills a large cup with tea in order to quench his thirst. As he raises the cup to his mouth, however, he sees in it the face of a handsome young samurai, and yet there is no-one nearby to cast the reflection he initially believes it to be. Repeatedly the face appears and eventually the thirsty and frustrated attendant drinks the tea regardless. But is it only tea that he has swallowed?

The stories themselves are for the most part simple in structure (a reflection perhaps of their brief literary length), and in common with many works of horror fiction play out in part as straightforward morality tales. After many years of such stories from both eastern and western film and fiction, few nowadays will be startled by the individual outcomes (one is even given away by its title). But like Hoichi's recounting of the battle of Dan-no-ura, the real pleasure of the tales lies in their telling, and it’s Kobayashi's striking skill as a visual and aural cinematic storyteller that has earned Kwaidan its unique place in cinema history. And when I say unique I’m not being in any way hyperbolic – no other film looks quite like it, none I have come across sounds like it, and its seamless blending of theatrical, cinematic and literary elements creates a compelling sense of other-worldliness that at times seems to lift the tales out of their historical context and into an alternate dimension.

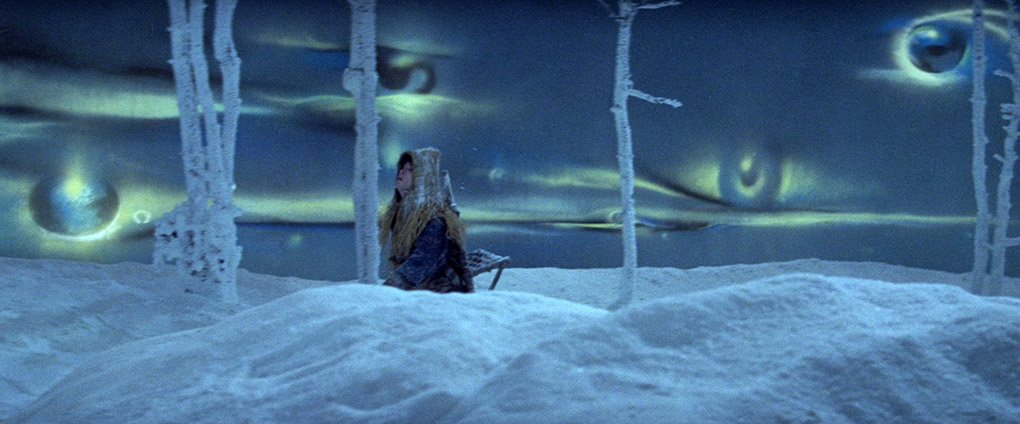

Sometimes surreal in its evocation of a waking dream or nightmare, the film is frequently expressionistic in the externalisation of the mental state of its characters. Visually it is rarely less than stunning, and I'm not talking the chocolate box prettiness of the likes of Memoirs of a Geisha but a beauty that is as haunting as it is breathtakingly imaginative, both in conception and execution. Miyajima Yoshio 's scope cinematography and Toda Shegemasu's art direction are extraordinary throughout but neither is superficially beautiful, always serving the story, the characters and the atmosphere, sometimes in semi-abstract or symbolic manner. This is most vividly realised in the second story, The Woman in the Snow, where red skies are peppered with gigantic watching eyes, the light in a room suddenly shifts to evoke a memory, and the sun is fragmented in the style a cubist painting.

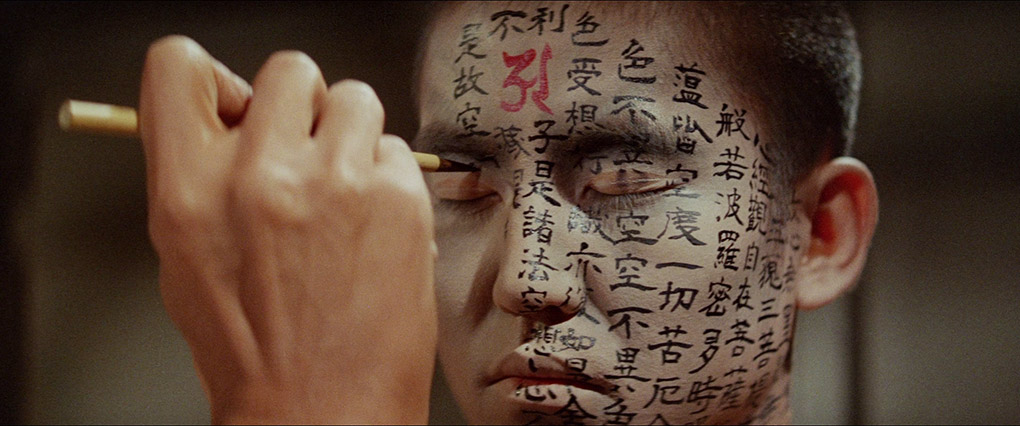

The film draws heavily on Japanese theatre, with the influence of Noh plays – in the sets, the lighting, and the movement of characters – being repeatedly evident and mesmerizingly realised. And yet the drifting camera and sometimes unexpected angles and movements occasionally recall the work of Kobayashi's cinematic predecessors, notably Mizoguchi Kenji, whose landmark supernatural tale Ugetsu monogatari appears to have been a partial inspiration here. This is particularly evident in the sequence in which spells are written all over Hoichi's body to protect him from evil, a vivid image that would also prove to be a crucial component of Peter Greenaway’s Japan-set The Pillow Book. Every bit as striking as the imagery is the haunting soundtrack, where natural sounds are often completely removed and action plays out either in silence or to the accompaniment of Takemitsu Tōru's almost avant-garde score. The sometimes stark use of traditional instrumentation blended with strangely altered sound effects (the climax of The Black Hair, for example, is peppered with the electronically treated sounds of breaking wood that are sometimes deliberately out of sync with the image) proves genuinely unnerving, emphasising the theatrical link and perfectly complimenting the film's bold and beautiful visual stylistics.

Of the stories themselves, Hoichi, the Earless is often singled out for the highest praise and it's not hard to see why, being as the most substantial of the four (reflecting the longer length of the original story when compared to the others adapted here) and without question the most structurally complex, the stylised visualisation of Hoichi's battle tale at first seeming like a splendidly realised but largely cosmetic inclusion – only later do we realise just why we were shown it in such detail. But this should in no way reflect negatively on the other three stories, all of which, although shorter and more straightforward in their storytelling, are every bit as compelling and rich in their detail. Some of this may fly over the heads of a non-Japanese audience or at least those unfamiliar with Japanese history and customs (I’ll freely admit that I needed help from my Japanese partner on this score). The significance of the title of the first story, for instance, relates in part to, a traditional Japanese ghostly figure known as a yūrei, one that has the appearance of a white-dressed woman with long black hair, something western audiences have since become familiar with thanks to the international success of horror works such as Ringu and Ju-on. The Snow Woman, meanwhile, would likely be instantly recognised in Japan as ghostly because her white kimono is identical to the ones in which the bodies of the recently departed are dressed for funeral services, and following his encounter with her Minokichi meets and marries a woman named Yuki, the Japanese word for snow. The fireballs that glide through the air as Hoichi is led to his new assignment are a traditional Japanese representation of the spirits of the dead, and while not as significant, it’s still worth noting that older marriage rites required the bride to blacken her front teeth for the wedding, something that here could be mistaken for a toothless smile. But the film never relies on our knowledge of such details, and the underlying themes and morals of the tales themselves are universal enough to be easily understood and appreciated by any receptive audience.

Although the four stories are in no way connected and indeed have distinct stylistic differences to each other, there are still thematic and narrative links that bind them into a cogent whole. The importance of agreements is central to the first three stories and the breaking of them, for whatever reason, is shown to have serious consequences for willing and unwilling transgressors alike. The fact that women are twice wronged by men, meanwhile – whether it be a promise or a declaration of marriage – who then suffer the consequences of their actions is a common element in Japanese ghost stories and films. Most vividly, though, the film creates the sense that the spirit world does not consist of a few ghosts trapped in limbo, but is a very tangible and populous place that co-exists with the land of the living and whose inhabitants are more powerful than even the most ferocious warrior. One thing is very clear – if you enter into an agreement with a spiritual being, break your word at your peril, and if you are going to protect yourself, then in the name of the gods, do a proper job of it.

As I've already said but is worth repeating, it's not so much the stories themselves but the spellbinding manner in which they are told makes Kwaidan such a magnificent and widely praised work of cinema. It combines the majesty of grand opera, the unhurried and almost abstract minimalism of Noh theatre and the visual poetry of painting into a work that is intensely cinematic whilst remaining true to its literary roots. A beautiful, compelling and genuinely chilling masterwork of film storytelling, Kwaidan imbues the poetic simplicity of Hearn's original tales with an almost Shakespearean grandeur, and in a manner that manages to be artistically thrilling even as it sends serious shivers down your spine.

Back when I reviewed the Masters of Cinema DVD release of Kwaidan in 2006, I was particularly impressed with how good it looked on that disc. Of course, a lot has changed in the 14 years since that edition hit the shelves, and the baseline for what constitutes a top-notch transfer has evolved with the switch from widescreen CRT TVs to 1080p HD flat screen monitors and the arrival of Blu-ray as a delivery medium. And while the 2006 Kwaidan DVD still looks good for a standard definition anamorphic transfer of the film, it just can’t compete with a decent HD restoration of a film from any era. Enter the 2K restoration carried out by the Criterion Collection that was the source for the 1080p transfer on this Blu-ray, which is everything you’d seriously want of such an upgrade. The detail is considerably more distinct and sharply rendered here, the colours even richer and the contrast has a little more finesse than the already impressive range on Eureka’s DVD. There is also a complete absence of compression artefacts on clear blue skies, something just visible on the DVD transfer when viewed on a large screen HD monitor. Honestly, the film looks utterly gorgeous here, beautifully showcasing the film’s striking scope cinematography, art direction and distinctive use of colour and shading. Only in the first close-up of Hoichi did I spot obvious signs of any former damage.

One area where the Eureka DVD lost out to its Criterion equivalent was the mono soundtrack, which unlike the cleaned-up Criterion one displayed some audible wear and tear in the shape of low level background crackle, not ideal for a film which makes such expressive and disconcerting use of silence. Given that this transfer was sourced from Criterion, it’s no surprise that the Linear PCM 1.0 mono track here is devoid of any such issues boasting clear reproduction of dialogue and especially sound effects and music.

Optional English subtitles have been included and switch on by default.

Shadowings: A Video Essay by David Cairns (35:45)

Despite the above title that appears on the Special Features menu, this video essay is by David Cairns and Fiona Watson, and it’s a damned good one, so both deserve full credit here. Alternating the duties of narration, Cairns and Watson deliver a thoroughly researched and thoughtful examination of what Watson describes up front as “one of the most outrageously beautiful films ever made,” exploring the background to its making before analysing each of the four stories in fascinating detail. Obviously not one to watch before seeing the film for the first time, but an educational visit after you have.

Kim Newman Interview (24:24)

Writer, critic and horror devotee Kim Newman takes a typically engaging look at what for many years was the highest profile Japanese supernatural-themed movie outside of its native land. Newman notes how faithful the adaptations are, how the archetypal characters could almost have been plucked from fairy tales, suggests the stories have a film noir element to them, and speculates on why of all the Japanese ghost story films of the era, this was the one to break through internationally. In common with Cairns and Watson above, he examines each of the stories in detail, though from a largely different perspective, which ensures there is little crossover between these two extras. He also intriguingly remarks that the full-length version (that’s the one on this disc) somehow feels shorter than the cut-down one that was originally released in the west and concludes by noting that the film “is indeed a masterpiece.” No argument here.

Three original Japanese Trailers have been included and all are in surprisingly good shape, given their age. The B+W Japanese Teaser (1:07) kicks off a tad ironically by announcing that the film is in colour, then makes great play of its cast and its director, includes a couple of shots of behind-the-scenes action and concludes with the announcement that “Filming is going smoothly!” Presumably that was before the money ran out and director Kobayashi had to sell his house and his golf club memberships to raise the money needed to complete it. The Colour Japanese Teaser (1:25) is a fascinating concoction that makes the film look as avant-garde as the unsettling strains of Takemitsu Tōru's score that it is set to. Finally, the Japanese Trailer (3:58) gives a clearer idea of the content and style of the film as a whole and concludes by describing it, rather wonderfully, as, “A drama of human passions grappling with demons and obsessions – a work of fantasy and lyricism.”

Booklet

I was convinced I’d been sent a PDF of the booklet that accompanies this release, but despite searching my inbox repeatedly I could find no trace of it. Never mind. From the description in the press release – ‘a 100-page perfect bound illustrated Collector’s book featuring reprints of Lafcadio Hearn’s original ghost stories; a survey of the life and career of Masaki Kobayashi by Linda Hoaglund; and a wide-ranging final interview with the film maker’ – it would appear to be very similar in content to the one that accompanied Eureka’s 2006 DVD release, and that was excellent, so I have similarly high expectations for this.

My disc library is littered with HD upgrades of films I already own on DVD, and while picture and sound improves are the usual prime motivations for such a purchase, we always kind of hope any new edition will be supported by some previously unseen special features as well. So gorgeous are the visuals of this extraordinary film and so important the soundtrack that here the sound and picture upgrade would justify the purchase of this Blu-ray alone, but the two new special features are both first-rate. A lovely release from Masters of Cinema that comes highly recommended.

This review has been updated from our 2006 review of the Masters of Cinema DVD release.

The Japanese convention of surname first has been used for all Japanese names in this review.

|