Note: In order to discuss some aspects of the story, their impact, and the questions they raise, I'm going to have to reveal some plot details that I'd normally avoid mentioning. As many of you will be as unfamiliar with this film as I was until I watched this disc, I'm going to include spoiler warnings at two key points in the review and the ability to skip past them to the relative safety of the final paragraph.

If you're someone who dislikes seeing women violently abused by men – and if you're not, it may be time to get some serious help – then the opening scene of Katō Tai's 1968 I, the Executioner [Minagoroshi no reika] is almost definitely going to prove problematic viewing. It opens on the terrified face of a woman as she slowly backs away from the camera, only to be then knocked unconscious by an open-handed punch to the face. Her unseen male assailant then rips the telephone from its socket, lays the woman down on the floor, tears open her nightdress, then throws it closed again with a contempt that I initially mistook for frustrated disappointment. He then jumps to his feet and grabs a discarded stocking, which he uses to tie the now naked woman's hands behind her back, then drags her into to the en-suite bathroom. With her mouth held open by the telephone cord he has wrapped around her neck and face, he secures her head to the shower tap with a rolled-up towel, and wakes her by spraying her face with water from the shower. He then breaks off a large piece of waste pipe and starts to beat her viciously with it, causing her to cry out repeatedly in pain. He then grabs the woman by the chin and lifts her head to face him and she gives a single slow nod. He then drags her back to the bedroom and slaps a notepad and pen down on the bedside table before her and shoves her aggressively towards it, where she is forced to write down the names of four other women and the cities in which they live. The man then lays the woman down on the bed, pulls her legs apart and rapes her, over which the names and the faces of the four listed women appear in double-exposure. The man then takes out a knife and stabs the woman hard in the chest, in the process inflicting an accidental cut to his hand. After staring at the wound with an expression of bemused anger, he clenches the injury into a fist and furiously beats the now dead woman around the face. He then rips off the notepad page containing the list of names, and as he washes his wounded hand in the bathroom sink, the dark blood clouds the water until it fills the screen, over which the main title then appears.

Despite being well versed in even the darker corners of modern extreme cinema, I was given a serious jolt by this scene. Admittedly, I came to it completely unprepared, but everything about how it plays out seems designed to disturb the viewer. And don't let that 1968 release date mislead you – the worst violence may take place just off screen or be masked by furniture, but the inference is still deeply unpleasant, and there's no music score to soften the soundtrack. There's also an almost clinical aspect to the framing, with almost the entire scene playing out in close-up, primarily on the face of the victim or the hands of her killer. Only when he lifts his wounded hand to examine it do we get to see the murderer's face, and frankly it's not a comforting sight, a tribute to actor Satō Makoto's weather-beaten features and the twisted fury of his expression.

At this point, the attack does feel like the random act of a homicidal madman, a view seemingly confirmed by the killer's hatefully unhinged response to his accidental injury, but there are small suggestions here that not all is as it initially seems. The most significant clue is that list of names that the man tortures the woman into writing. Is he simply seeking the names and locations of some future potential victims, or is their connection to her relevant to his actions and intentions? That she has resisted giving them up until this point can be deduced from the cooperative nod she has to be tortured to give, and when dragged back to the bedroom after the bathroom ordeal, the look she flashes to her assailant is not one of fear but of undisguised hatred. Did the two know each other before this attack?

No clear answers are provided by the police as they investigate the crime scene while the title credits unfold, despite finding that list of names through the old favourite method of rubbing a pencil over the indentations on the notepad caused by the pressure of the pen. Even once back at the office, the lead detective (Matsumura Tatsuo) – whom we meet lying sideways on his desk and wincing with pain from a bad case of piles – and his assistant (Hodaka Minoru) appear to have little to go on. They reveal that the victim was a bar hostess, making reference to a similarly violent murder that occurred ten years earlier, and discover that the first on their list of possible suspects has an iron-clad alibi for the time the woman was killed. In the very next scene, however, a few crucial facts emerge. We learn, for instance, that the murdered woman's name was Yasuda Takako, while the fact that she was close friends with the four women on her list is confirmed by their attendance and conversation at her wake. The late-arriving Misa (Kin Sugai) brusquely lights some incense and angrily complains about the placement of a group photo featuring all five women instead of the traditional solo portrait. "It's an ill omen!" she barks as Misoa (Tōda Junkō) weeps, only to be told by Keiko (Sanae Nakahara) that the police have taken all the portrait photos to assist with their search for suspects. Misa, Keiko and Misao then make work-related excuses to leave, leaving the quieter and more compliant Kyoko to keep the traditional vigil alone.

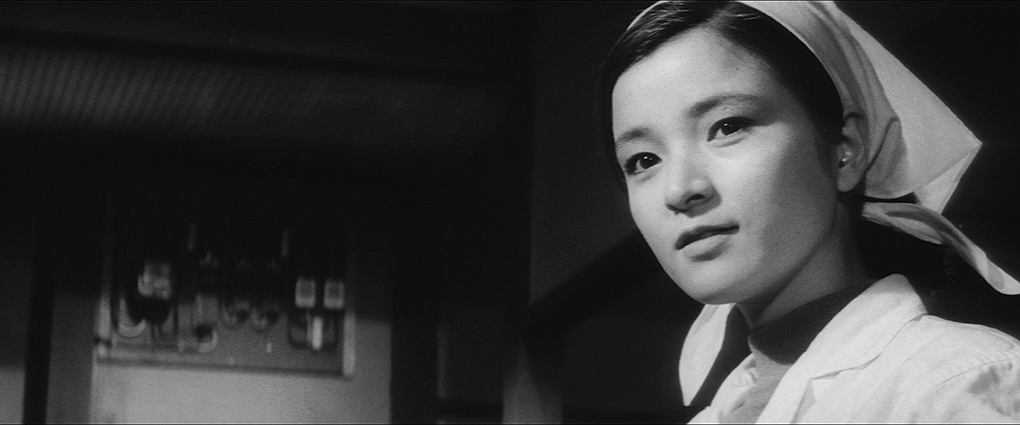

The re-entry of the killer into the story is economically handled, with a ground-level shot showing the feet of a man as he approaches a small restaurant in the pouring rain cutting to a close-up of a bandaged hand holding newspaper over the owner's head as an improvised hat. The restaurant is run by an elderly man and his pretty adult daughter, Haruko (Baishō Chieko), both of whom inform this mysterious figure that the restaurant is now closed. When he sits down regardless and states that "anything will do," I began to get worrying A History of Violence vibes and became instantly nervous for the safety of both restaurateurs. The upbeat Haruko agrees to serve the man – who calls himself Kawashima but whose true name is Shima Isao – as long as he wants something simple. To my considerable surprise, he then sits quietly and tucks into his food, ignoring the kerfuffle in the background caused by the restaurant's young goon of a delivery boy, the nearest the film has to a comedy relief character. As Isao eats, Haruko throws him a curious gaze, and once again I became concerned for her future wellbeing, but as with the opening sexual assault and murder, not everything here is quite what it seems.

And here comes the first of those two spoiler warnings I mentioned above. Whether the details revealed in the following three paragraphs really qualify as spoilers is a matter for debate, as everything covered takes place during the first half of the film, and the main point of discussion is alluded to in the opening scene. But if you think you've heard enough, feel free to hop forward to the final paragraph, or click here to do so automatically.

It is soon confirmed that Isao is not randomly targeting women, and that he has a specific reason for hunting down Takako and her four friends. We're invited to speculate on what that reason might be when it's revealed that a 16-year-old laundry boy named Kobuku Kiyoshi threw himself off the roof of the very apartment block in which Takako lived and in which she was murdered. Any doubts on this score quickly dissolve when Isao visits the laundry at which Kiyoshi worked in order to pay his respects at the butsudan set up in his memory by the talkative female proprietor. It's she who reveals that the boy was saving diligently from his wages in order to start his own store to support his family, hardly the actions of a boy planning to take his own life. The only person to initially suspect a connection between the two incidents is dorky but dedicated police constable Kameoka, but when he takes his suspicions to the detectives in charge of the case he is initially dismissed as a well-meaning timewaster. That link is seemingly confirmed after Keiko is also murdered by Isao, and the now nervous Misao and Kyoko express their concern that the two deaths are related to "that day…the day that we…" It's an unfinished sentence that is curtly dismissed by Misa, but one that hangs in the air for the audience to draw its own conclusions from.

Isao's growing friendship with Haruko, meanwhile, appears to be completely and unexpectedly genuine, and starts to reveal an altogether different and even softer side to his initially ice-cold personality. She is even able to put a smile on his face when she talks about wanting to lead a short but full life rather than a long and empty existence, a smile that sharply vanishes when she attempts to reads his palm and suggests that his lifeline indicates that he will soon die. "Or perhaps you're already dead," she quips, prompting him to slam his water glass down so sharply that it showers them both with its contents. For Isao, Haruko represents an unexpected potential for redemptive transformation, in much the same way that Reba McClane later would for serial killer Francis Dolarhyde in Thomas Harris's 1981 novel, Red Dragon. The parallels between these two otherwise very different works extend to a peculiar desire on our part to see Isao turn his back on his grim quest and walk into the light, despite knowing in our gut that fate has something altogether different in store.

Only in retrospect was I able to appreciate the purpose and economy of Katō Tai's direction of even the most uncomfortable scenes. Deliberately confrontational and startling though the opening murder most definitely is, by shooting it almost exclusively in restrictive close-up, Katō forces us to focus on the suffering of the victim whiles avoiding any hint of violence glorification. He also understands that we only need to see an assault portrayed in such detail once for its impact to register. The second rape and murder – once again shot as a series of close-ups of the victim – is still unpleasant, but less jarringly violent than the first, and the third is not shown at all, cutting instead from the unwary victim kissing and dancing drunkenly with a repulsed Isao in a dockside bar to a shot of her naked and lifeless body floating in the water nearby.

And now it's time for that second spoiler warning, as I'm about to reveal a key plot point from the film's second half, and am only doing so at all because it raises a couple of questions that I really feel the need to address, if inconclusively. Thus, if you want to avoid finding out what happens later, skip the next two paragraphs or click here to do so automatically.

It's only when the pieces start to fall into place later that the most intellectually intriguing aspect of the film becomes clear. It emerges that the teenage Kiyoshi was driven to suicide after being effectively gang-raped by the five women that Isao is hunting down and killing. It's a revelation that gender-inverts the central premise of the rape-revenge subgenre-to-be*, one that forces us to question the morality of actions that that traditionally deliver dark cathartic pleasures. This moral quandary is even addressed by characters within the film itself when two of the investigating detectives are debating the case. One of them suggests that if his partner was raped by five women then he'd enjoy the experience, but that it would be a different story if his own sister was raped by five men, on each of whom he would take revenge. "I mean," he says, "for a man, the conditions are a lot different." This is emphasised by his partner's belief that what the women did would not constitute a crime under Japanese law of the day.

This raises a still-pertinent real-world issue in which sexual assault – at least with adults – tends to be seen as a one-way street, as a crime that simply cannot be inflicted on men by women. Yet as the high-contrast flashbacks here reveal, the innocent young Kiyoshi was not a willing participant in what the women clearly regarded as a bit of saucy fun, and he was left deeply traumatised by the experience. As the detective infers, had the boy been raped by five men we would doubtless be on Isao's team from the off. But if the killing of male rapists is justified within the context of the story, should the same punishment not also stand if the attackers are female? More to the point, if we recoil at the idea of this man murdering women for this crime, should we not feel the same if he was executing men for the same? We should, but we don't, and usually with good reason, and by forcing us to confront the full implications of that question, the film provides plenty of discomforting food for thought. Without getting even more specific about how things play out, Isao's situation is complicated further by his discovery that he and Haruko have more in common than first impressions might suggest. It's something that's delicately and touchingly danced around in a beautifully performed and gorgeously shot riverside conversation between the two that – pictorially, at least – looks almost as if it could have been lifted from F.W. Murnau's Sunrise. Then, just as we move into the climactic scene, the film executes an unexpected rug-pull that in some ways flips what has become a gender-inverted rape-revenge story almost back to where it first seemed to have begun.

I'll admit that until I watched the special features on this disc, I was unaware that I, the Executioner was one of a whole string of Japanese films built around true life and fictional serial killers, despite being a confirmed fan of one of the most famous, Imamura Shohei's 1979 Vengeance is Mine [Fukushū suruwa warenai]. That's certainly the work that most readily came to mind when watching Katō's film for the first time, despite their differences in plot and character and directorial style. Both make for often uncomfortable viewing, and both are built around compelling central characters whose fate I found myself invested in despite being appalled by their actions. Yet as with Imamura's film, I, the Executioner is also a carefully constructed and ultimately rewarding work. The foundations are laid in the precision-structured screenplay by Mimura Haruhiko, Yamada Yōji and director Katō, from a story by Hiromi Tadashi, in which I gather the killer was female. Every character here is quickly and economically defined, with an excellent cast bringing personality and a hint of backstory to even the smallest role, while Katō's direction is impeccable throughout, particularly his expressive use of facial close-ups and the narratively purposeful use he makes of cinematographer Maruyama Keiji's scope compositions. About Kaburagi Hajime's cocktail lounge music score I was a little less certain, at least until I heard filmmaker Fukusaku Kenta in the special features commenting on the appropriateness of the score around a chorus of female voices. The result is not the most comfortable or upbeat watch, but is a consistently gripping, commandingly performed, and arrestingly directed work nonetheless, one that may openly confront and challenge the viewer, but in a manner seemingly designed to provoke debate and a rethink of the way we view and respond to such cinematic tales.

I don't have many details about the source for the 1080p transfer on this Radiance Blu-ray, other than the fact that it was carried out by the film's production studio, Shochiku, but it's clearly undergone an HD restoration, though whether that was from the original negative is uncertain. Framed in the original scope aspect ratio of 2.40:1, the monochrome image here is crisp, with a pleasing, sometimes almost silvery contrast range, and while the black levels are just a whisper short of rock true black (having pitch-black borders above and below the image does tend to highlight this) and do swallow a little of the shadow detail it places, they are at a consistent level throughout the transfer. The picture is also largely clean with only a small number of dust spots on the occasional shot, and a fine film grain is visible throughout, and while there is some very mild brightness pulsing on a couple of scenes, this is only likely to be noticed by the more critical eye. On the whole, it's a really fine job that really showcases the strengths of Maruyama Keiji's cinematography, particularly his use of light on facial close-ups and that lovely riverside conversation scene.

The original Japanese mono soundtrack is presented here as Linear PCM 2.0, and despite an unsurprisingly narrow tonal range, the dialogue, effects (check out Haruko's scratching of a particularly relevant piece of paper during the riverside scene) and music are all decently clear. There are traces of minor background fluff and crackle if you crank up the volume, but this is never loud enough to be distracting.

Optional English subtitles are available and are activated by default.

A Serial History (16:07)

A hugely useful visual essay, narrated by Tom Mes and written by Mes and Jim Harper, that traces the history of Japanese serial killer films, which astonishingly began back in 1899, just three years after cinema came into being. A sprinkling of my personal favourites are touched upon and sometimes examined in more detail, including the above mentioned Vengeance is Mine (Fukushû suruwa warenai, 1979) and Kurosawa Kiyoshi's haunting Cure (1997), but there were also plenty of titles I've never seen, providing me with a useful shopping list for future viewing. The essay is illustrated with a mixture of film clips and stills from the films and filmmakers under discussion.

Appreciation by filmmaker Fukusaku Kenta (19:45)

Fukusaku Kenta, probably most famous outside of Japan for co-writing Battle Royale (2000) and Battle Royale II (2003), and for taking over the direction of the second film following the death of his father, Fukusaku Kinji, the veteran original director of both works. Here, he expresses his admiration for the cinema of Katō Tai, his directorial style, and his preference for characters that are true to life. He touches on the leftist politics of Katō's work and his collaboration with screenplay co-writer Yamada Yōji, and describes I, the Executioner as Katō's "most hellish film." He also proves to be a man after my own heart when he states categorically, "I can't imagine what my life would be like without films." Absolutely.

Trailer (3:55)

An ever-so-slightly sensationalist trailer peppered with captions like "Frenzy at noon" "Dripping with fresh blood," and "So lurid you can't bear to look." Another caption that begins with "Taking care of…" has not aged well at all. There are also some serious spoilers here, so it's worth avoiding this until after you've seen the film itself.

The release disc also includes a Limited Edition Booklet featuring new writing by Tony Rayns and a new translation of archival writing on the film, which I'm keen to read but which I did not have access to at present.

As is often the way with Radiance releases, I, the Executioner is a film with which I was previously unfamiliar, and the paucity of reviews on its IMDb page and the complete absence of a Wikipedia page suggests that I am probably not alone here. It's a confrontational work, no question about that, but also an intelligent, smartly made, convincingly performed and unexpectedly moving one that is absolutely worth toughing out that opening scene to appreciate. The presentation on the Radiance Blu-ray is top notch, and as with the label's simultaneously released Death Occurred Last Night, the special features may be limited in number but are still excellent and informative companions to the film. This won't be for everyone, but for those willing to embrace the darkness, it comes highly recommended.

The Japanese convention of family name first has been used for all Japanese names in this review.

|