| |

“It is true, we shall be monsters, cut off from all the world; but on that account we shall be more attached to one another.” |

| |

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (formerly Mary Godwin) |

To say that the summer of 1816 was a washout would be meteorological understatement of the century. In Europe, the temperatures were the coldest of any summer on record, the result of a volcanic winter caused by the massive eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia the previous year. But for horror fans, this was to be the most important summer in the history of a genre that had yet to be invented, one that gave birth to one of the greatest and most influential of all horror novels, as well as laying the groundwork for a second, equally genre-defining work.

In the May of that year, poet and philosopher Percy Bysshe Shelley took a trip to Lake Geneva to visit fellow poet Lord George Gordon Byron at the stately Villa Diodati, at which Byron was staying with his doctor, John Polidori. Accompanying Shelley on this trip was his 19-year-old lover Mary Godwin, their young son William, and Mary’s stepsister (and Byron’s former lover) Claire Clairmont. A controversial figure in the days when the behaviour of poets could be regarded as scandalous, Byron had left England for Switzerland to escape his creditors and gossip about his recent divorce and his colourful personal life, including a rumoured affair with his half-sister Augusta Leigh, with whom he may or may not have fathered a child. Effectively trapped inside the Villa by constant rain showers, the five took to reading German horror stories, which led to a competition in which they were all encouraged to invent their own, the most celebrated of which was created by Mary and would be published two years later as Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus. Polidori meanwhile, developed a story told by Byron into a novella that was published in 1819 as The Vampyre, which is generally considered to be the birth of the romantic vampire genre and a direct influence on Bram Stoker’s seminal Dracula.

It's speculation on what occurred during this meeting of creative and free-spirited minds that is the basis for Gothic, the first feature script by screenwriter Stephen Volk, and the project that saw director Ken Russell return to the UK after a spell in Hollywood that resulted in to two cult classics in the shape of Altered States and Crimes of Passion. On paper, this might seem like a perfect match of subject matter and director, a chance for Russell to revisit the ensemble period pleasures of the likes of Women in Love, perhaps? But this was the post-Tommy, post-Lisztomania, post-Valentino Russell, who was regularly being criticised for his flamboyant excess, and Volk’s screenplay was no gentle parlour piece, but a fusion of factual drama and existential horror. Was giving this script to this filmmaker at this stage of his career really a good idea? Back on its 1987 UK release, I wasn’t completely sure. Returning to it many years later on the BFI’s sparkling new Blu-ray, it seems like a perfect fit, and I now genuinely cannot imagine this film being made by anyone other than our Ken.

The foundations for a fascinating film are all there in Volk’s carefully crafted screenplay, which compresses the events of several summer evenings into a single wild, intense and drug-fuelled night in which all of the characters are brought face-to-face with their most deeply-held fears. The film begins with a brief bit of scene-setting as a group of scandal-hungry tourists observe the Villa Diodati through a telescope from a distant shore, and Dr. Polidori (Timothy Spall) stands at a window offering a gentle wave to what he and Lord Byron (Gabrielle Byrne) have doubtless become wearily accustomed to. A short while later, a rowing boat reaches the shore carrying the exuberant trio of Percy Shelley (Julian Sands), Mary Godwin (Natasha Richardson) and Claire Clairmont (Myriam Cyr). Crucially, Volk elected not to include William in this scenario, though his existence is acknowledged and his death three years later foreseen in the visions that plague Mary during the course of this fateful night.

That Byron was surprised by Clare’s arrival and intermittently irritated by her presence appears to be true to what we know of that summer, as does his alternatively combinative and almost intimate relationship with Polidori, who clearly has a bit of a thing for this enigmatic poet. Mary’s melancholia and Shelley’s mental fragility at this time are also a matter of record, as is the group’s belief in the notion of free love, and while I’ve not been able to find written confirmation from my casual research, the free availability of the opium-derived drug laudanum at the time makes the film’s suggestion that it was freely ingested an easy concept to swallow (pun sadly unintended). That there was a bond of artistic mutual admiration between Byron and Shelley has been widely acknowledged, and that Mary was haunted by the premature birth and death of her first child by Shelley also appears to have been likely in a woman who suffered regularly from depression, but who nevertheless eagerly soaked up the philosophical and literary discussions that took place in the stormy evenings in the Villa Diodati. So far, so factually sound, but having compressed events into a single evening for dramatic effect, Volk uses this meeting of troubled but creative minds, together with the proposal that they each devise their own horror story, as a catalyst for the creation of a monstrous but ultimately unspecified force that is unleashed within the house. Born of the subconscious fears of its creators, it proceeds to hold up a mirror to their personal terrors, driving each of them to the brink of murderous or suicidal madness.

This is where the very specific talents of director Ken Russell come in. Everything about this scenario plays to his strengths as a filmmaker, from the larger-than-life historical characters to the laudanum-fuelled nightmare of desire and terror into which the characters subsequently descend. Despite Volk’s initial apprehension at the idea that his first screenplay would fall into the hands of a director like Russell, the two seem to be working in true harmony here, as what begins deceivingly as a lively heritage drama gradually mutates into a thematically layered Hammer horror movie where dreams and hallucinations become almost indistinguishable from reality. Hammer is not the only influence here, with the slime that acts as the first signs of the monster that the group has invoked recalling the pool of goo found in the air shaft by Captain Dallas in Alien, while imagery elsewhere recalls a range of genre works from The Exorcist to The Wicker Man. There’s also a direct line here to Gasper Noé’s 2018 Climax, a film in which LSD spiked sangria results in each member of a company of dancers descending into their own private hallucinatory hell. The difference here is that while Noé approached this collective collapse into madness from an observer’s viewpoint, Russell and Volk take a more subjective view, getting inside the heads of this small collective of writers and dramatising their nightmare visions.

It’s here that a little knowledge of the real-world lives of the gathered individuals goes a long way, as what to the untrained eye might seem like random behaviour or recycled horror imagery is almost all directly relevant to the past, present and future fates and phobias of individuals here. It’s worth knowing, for instance, that Byron had a club foot about which he was doubtless a little sensitive, hence his angry response to Claire’s playful claim that he’s the Devil and jokey attempt to take a peek at his ‘cloven hoof’. When Shelley investigates a noise in a nearby barn one stormy night and is thrown into a panic when he falls through rotten floorboards, meanwhile, he is unknowingly prefiguring he own death and burial just a few short years later, an event that Mary later foresees in more explicit clarity and detail. Particularly intriguing is how these visions and the actions of the party often contribute details to the story that Mary will eventually write, from Shelley standing naked on the rooftop during a thunderstorm in an attempt to summon the life-giving power of lightning, to the automatons that Byron keeps as playthings, and the mechanically moving, armour-dressed creature that haunts Mary’s nightmares. Indeed, in the climactic stages it’s Mary who becomes the film’s prime focus, as her reality collapses and she finds herself trapped in black-painted circular room with six doors, each of which offer disturbing and twisted glimpses into her past and future. Russell visually reflects Mary’s panic, confusion and claustrophobia with his shot choices here, an expressionist element emphasised by a use of wide shots and dramatic angles, a technique put to particularly disconcerting use when observing Polidori’s breakdown and a bungled suicide attempt that again acts as a piece of grim foreshadowing.

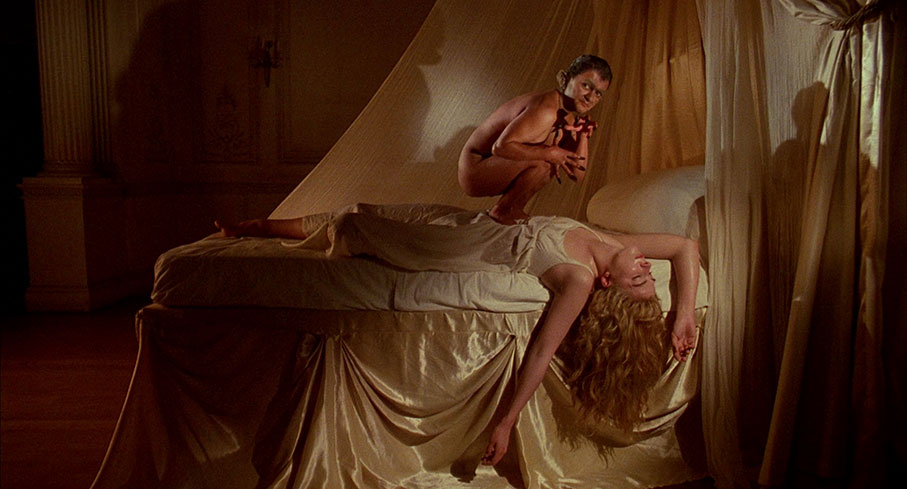

Elsewhere, Russell’s simultaneous embracement of and lingering doubts about Catholicism is woven into the fabric of the film, most prominently in a sequence in which the erotically charged image of Byron going down on the possibly dreaming Claire is intercut with the jealously tortured Polidori lying on his bed in the next room. As Claire cries out in pleasure, Polidori reaches out to a crucifix on the wall above his bed and topples it to floor, then slams his hand against the nail from which it was previously hanging, a punishing act of penance to control his sexual urges that leaves him with a self-inflicted stigmata in his palm. You can read what you like into the fact that when Byron raises his head from between Claire’s legs his lips are bloody – is this menstrual blood that proves Claire was lying about being pregnant with Byron’s child (real world spoiler – she wasn’t), a symbol of the abortion that Byron casually suggests to Mary that even Polidori could perform, or the vampiric inspiration for the story that will later inspire the doctor’s genre-defining novella? Feel free to add your own interpretation here. And when it comes to iconic shots, Russell alone was responsible for the sequence in which Henry Fuseli’s 1781 painting The Nightmare is brought startlingly to life, an image that proved so disturbing that posters on which it featured were promptly banned from the London Underground for breaking its advertising guidelines.

In typical Russell fashion, the casting is spot-on. Gabrielle Byrne makes for a bewitchingly enigmatic and authoritative Byron, a conductor of his own social orchestra who can switch on a dime from misogynistic seducer to tender comforter or furious controller, all of which Byrne radiates with utter conviction from the moment of his Count Dracula-like introduction. Julian Sands copped some unfair flak for what some regarded as an over-the-top portrayal of Percy Shelley, but for me he perfectly captures the poet’s mental fragility, insecurity and passion for his art, which when combined, intermittently take him to the edge, one that Sands nonetheless just pulls back from toppling over. And if you’re talking madness, just watch where Timothy Spall takes Polidori during course of that character’s emotional downward spiral. Myriam Cyr plays Claire as a ball of seductive energy, really letting rip during the sequence in which they summon the creature of their fears, while her ability to bulge her eyes wide makes the factually-based moment when Shelley sees her nipples replaced by human eyes all the more unsettling. Best of all is Natasha Richardson in her first film role as Mary, a sublimely pitched performance that presents her character in a sympathetic light from the off, yet later Richardson is able to take the character to extremes of terror and distress later without ever drifting into the realms of dramatic hysteria.

As was so often the way with Russell’s later works, Gothic was initially dismissed by many critics for whom the Merchant-Ivory model was the baseline of respectable restraint for period dramas. The director’s energy and willingness to cinematically reflect the emotional descent of its characters were once again misread as another example of Russell’s overly flamboyant excess, and his willingness to experiment further evidence of his complete lack of control, a viewpoint I neither share nor understand. Visually, the film is consistently gorgeous, thanks in no small part to the lighting and creative framing of former documentary and TV cameraman Mike Southon (who also lensed Bernard Rose’s visually arresting 1988 horror tale Paperhouse), and the work of production designer Christopher Hobbs and art director Michael Buchanan, both of whom worked on Caravaggio the same year for director Derek Jarman, who designed the extraordinary sets for Russell’s 1971 masterpiece The Devils. Russell regular Michael Bradsell’s editing is consistently sharp and moves the film forward at a sometimes breathless pace, and the air of encroaching and sinister madness is enhanced by a widely varied and intermittently (and most effectively) discordant electronic score by musician Thomas Dolby, who at the time was better known for his hit single Hyperactive and She Blinded Me With Science.

In an age of committee filmmaking, a film as stylistically distinctive and adventurous as Gothic has, for me at least, aged like a particularly exciting wine. It’s an arresting, breathless and hugely imaginative speculation of a short and intense period of rebellious creativity whose impact can be still felt on the horror genre over two centuries later, and while Russell may be working on a smaller canvas here than those of his then recent American projects, it still serves as a welcome reminder of how well and how creatively this man could paint.

A clean, robust 1080p transfer from what I presume is an MGM restoration in the film’s original 1.85:1 ratio, with well-defined detail, nicely balanced contrast, solid black levels, and an attractive reproduction of the warmly toned interiors and cool night-time exteriors of the film’s colour palette. A fine film grain is visible and remains consistent throughout.

The film’s soundtrack is presented here in Linear PCM 1.0 mono, and has an impressive tonal range for a mono track, with always clear dialogue and strong presentation of ambient sound and Thomas Dolby’s score. Despite indications to the contrary, however, there is more.

Tucked away on the fourth audio track (tracks 2 and 3 are devoted to the commentary and the Guardian lecture detailed below) and not mentioned at all on either the packaging or the disc menu, is a second soundtrack, and this one's in Dolby 2.0 stereo and frankly leaves the mono track standing. Boasting an even more sprightly tonal range, with crisper treble and punchier bass, it's louder than the mono track and boasts very distinct stereo separation throughout

which really bringing the music and especially the ambient sound effects to life, particularly during storms and the climactic descent into madness. I'm going to tip my hat to fellow reviewer Gary Couzens for alerting me to the presence of this track, and to the Facebook post by the BFI's Ben Stoddart that states, "The US (and I think German) release only has mono audio. We thought we'd include a stereo track after some colleagues investigated it and then contacted MGM, but the artwork had already gone to print." Although not accessible from the main menu, you should be able to access it by cycling through the audio tracks using your player remote. It's an excellent track and definitely the one to go for.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are available. The disc is encoded as region B.

Feature Commentary by Matthew J Melia and Lisi Russell

Previously featured on the 2018 Vestron Collector’s Edition Blu-ray, this commentary by film historian Matthew J. Melia and Elize – aka Lisi – Russell, is essential listening for anyone interested in this film or in Russell’s work in general. A key reason, of course, is the fact that Lisi was not only Russell’s fourth wife, but was around for the filming of Gothic, and is thus able to provide the sort of background detail on the production that you just can’t get from even the most learned expert commentaries. She’s well teamed with Melia, a clear fan of the film whose thoughtful analysis of individual scenes, coupled with the connections he finds to other films repeatedly surprises Lisis She’s also the source of some fascinating information, including the news that Russell had previously wanted to make a film about Byron and Shelley with David Bowie and Marc Bolan in the lead roles, the fact that had he really enjoyed making this film, and the surprising revelation that when it came to genre movies he was a big fan of John Carpenter’s Halloween, Wes Craven’s Scream and David Cronenberg’s The Fly. There’s also a fun story about Stanley Kubrick calling him to ask how he found such great houses for locations and pausing the call to chase a distracting fly, and I learned here for the first time that Russell’s two favourite film people were Nicolas Roeg and John Boorman. A terrific inclusion.

A Haunted Evening (34:30)

A new and hugely engaging and informative interview with screenwriter Stephen Volk, whose first produced feature script this was and whose subsequent horror screenplays include the 1992 BBC mockumentary classic, Ghostwatch. He provides some welcome details on his journey from young horror fan to advertising copywriter writing scripts in his spare time, and talks about his inspirations, his fascination with a summer that gave birth to two of horror’s greatest icons, and takes us on a detailed journey through the process of actually getting the film off the ground. He admits to initially thinking that Russell was the director you least wanted attached to your first feature screenplay, and reveals that this saw his original opening and closing scenes – which he outlines – quickly jettisoned in favour of what we now see on screen. That said, he does seem to have got on well with the director, describing him as a teddy bear of gentleness, friendliness and support, and noting that his favourite moment in the film is one of Russell’s invention. He also admits to being unsure what he thought of the film on its release, but was gratified to see it years later and really like it. There’s lots more on great interest here.

The Fall of the Louse of Usher (82:39)

Shot in 2002 on mini-DV on which was doubtless a miniscule budget, this self-financed work is described in an unattributed quote on a previous DVD cover as “the ultimate home movie” and carries the tagline “Murder, Madness, Mayhem,” both of which are completely apt but only give the smallest flavour of what unfolds here. With no financial backers to comply with, Russell clearly revelled in the lack of external pressure and let his imagination run riot, clearly unconcerned about possible audience reaction or accusations of tastelessness or excess. The standard definition DV aesthetic certainly lends the film a home or even student movie feel, which is enhanced by some suspect Southern American accents and Russell’s own comically colourful portrayal of German psychiatrist Dr. Calahari.

The title clues you in to the inspiration, but The Fall of the House of Usher is just one of a string of Poe stories and poems that worm their way into the fabric a film in which plot plays second fiddle to the playfully absurd. Roderick Usher (James Johnston) is the former Dave Vinian-like lead singer of the rock band House of Usher, and as the film begins he’s on the run for the murder of his wife, Annabelle Lee (Emma Millions). When captured, he’s shipped to a psychiatric hospital run by the aforementioned Dr. Calahari with the assistance of seductive Nurse ABC Smith (Marie Findley). Initially absent from the picture is Roderick’s sister Madeline (Elize Tribble Russell), whom Calahari suspects may be involved in the crime and to whom Roderick appears to be more devoted to than he was to his wife.

To attempt further description of what plot there is would a fruitless exercise for what is essentially a work of comically surrealistic avant-garde. You get a sense that if an idea or an image popped into Russell’s head when writing or shooting the film, then he’d include it because, well, why the hell not? Thus, Dr. Calahari is assisted by a white masked Igor, a middle-aged mystic, and an Egyptian mummy; Nurse Smith secures Roderick’s cooperation by chaining him to a Poe-inspired pendulum that lowers a large kitchen knife towards his genitals after feeding him Viagra; and two of Calahari’s patients turn out to be female wrestlers with a long-standing rivalry, which they attempt to settle by fighting it out in the hospital conservatory as the camera-wielding doctor watches eagerly on. Not a scene or, at times, a shot goes by in which Russell’s sense of invention and delight in pushing the boundaries aren’t on display, and there’s even a garden party that feels almost like it’s riffing on Monty Python’s Ken Russell’s Salad Days sketch, a parody of a send-up of his own earlier work. Cheap as chips it may look at times and even a little wince-inducing in places, but I watched the whole thing with a wide if occasionally disbelieving smile on my face, and despite the cheerfully enthusiastic amateurism of some the performances, I thought musician James Johnston – who also composed the film’s Poe-themed songs – was pretty darned good as Roderick Usher.

Amelia and the Angel (26:49)

A young girl cast to play an angel in a school play ignores the orders of her drama teacher and sneaks back after the last rehearsal to borrow the angel wings that she wears in the role to show to her mother, only to have them stolen and destroyed by her brattish brother. Having been warned by her teacher that they are irreplaceable, she nonetheless heads out in search of substitute wings, which leads her on a series of unusual encounters that build to a meeting with a Jesus-like painter. Shot silent on (I think) 16mm black-and-white film with a score and narration added in post, this 1958 short from Ken Russell is a gently bewitching gem that showcases the skill and inventiveness he was demonstrating as a filmmaker from an early stage, particularly in his use of handheld camera and POV and dolly shots. The print is not in the greatest of shape, with snowstorms of dust in places and some minor damage here and there, but that’s absolutely worth living with that for the film itself. A lovely inclusion.

The Soul of Shelley (17:53)

Aw man... Shot back in 2017 for an earlier Blu-ray release (Lion’s Gate is credited, but research suggests Vestron), a sad pall can’t help but hang over this interview with actor Julian Sands due to his untimely death earlier this year whilst on a hiking trip. This is at its most discomforting when Sands talks about the difficulty of putting himself in the mindset to act dead for the scenes in which Shelley’s drowning and burial are foretold in one of Mary’s visions. And Sands is so full of life here as he looks back at how he landed what in some ways was a perfect role for him, having been fascinated by Shelley from an early age and even visited his grave whilst travelling in Europe, as well as being a fan of Ken Russell’s early cinema. He recalls the experience of making the film as a very positive one, and provides some interesting specifics about its making, his respect for Russell nicely summed up by his assurance that he wouldn’t have stood naked on a rooftop being battered by rain and wind for anyone but him. Intriguingly, he believes that there should have been more nudity and sexual activity in the film to more accurately reflect what happened during that summer, and when he saw the finished work, he admits to being blown away how emotionally visceral it felt. A valuable and frankly enthralling inclusion.

The Guardian Lecture: Ken Rus sell in Conversation with Derek Malcom (87:32)

Oh, is this a treat. Having had the pleasure of once conversing with Russell, I know what an entertaining and witty storyteller he can be, and in this onstage chat with critic Derek Malcolm (whom I also had the chance to chat to several years ago, while I’m dropping names) sees the filmmaker on excellent form. Malcolm’s introduction references Russell’s famous altercation with unsympathetic critic Alexander Walker, whom he hit on live TV with a rolled-up copy of his negative review of The Devils, and he proves adept at prodding the director for revealing and often amusing responses. A lot of ground is covered here, including the differences between British and American film crews and how this was changing, the initially disastrous preview screening of Altered States and how a better targeted second screening changed its fortune, problems with censorship and Crimes of Passion (“The nightstick going up the anus, you can’t have it twelve times you can have it seven”), being blown away as a young man by Michael Powell’s The Red Shoes and again later by Peeping Tom, the banning of his BBC Strauss film The Dance of the Seven Veils, and much more. Every bit as lively are his responses to audience questions that you’ll have to strain your ears to hear but that Malcolm handily often repeats. Included here are the details of an opera he directed in Italy that resulted in him needing a police guard, the problematic but changing issues of music copyright, choosing first-time composer John Corigliano for the Altered States score, and more. He reveals that he is a huge fan of F.W. Murnau, Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane, and the revered Jean Vigo double of L'Atalante and Zero de Conduite. When asked to name a modern film that he admires, my fellow scribe Camus will doubtless be delighted that he picks Richard Rush’s The Stunt Man as a rare work that he believes was made by a true filmmaker rather than a radio director.

Original Trailer (2:42)

A slightly misleading trailer that sells the film as an all-out, incident-packed Hammer-style horror movie.

Booklet

Leading the way here is an excellent essay on the film, its making, and its aftermath by film writer and lecturer, Ellen Cheshire, that takes its amusing title from a quote about the film by Natasha Richardson, Gothic? It Might Not Be Your Cup of Tea... Next up is a piece on Russell’s film work in the 1980s by film and TV writer Jon Dear, which should prove interesting to those not familiar with the director’s work during this period. When it comes to his curt dismissal of Altered States, however – a film that I and a good many others regard as one of the genuinely great works of science fiction cinema and one of Russell’s best – I personally think he is talking absolute tosh. Full credits are provided for the film (well, except the year of production and the running time), and credits and write-ups are provided for all of the key special features. I was also touched to find in the credits for this Blu-ray release that it has been dedicated to Julian Sands and Derek Malcolm, both of whom passed away earlier this year.

Coming back to Gothic was a hugely enjoyable revelation, reminding me again just how good a director Russell could be when he was paired with the right material, and Volk’s multi-layered script is certainly that. The BFI’s welcome Blu-ray release features a first-rate transfer, and is backed up by a frankly terrific collection of top quality special features. As Natasha Richardson says, it might well not be your cup of tea, but for fans of the film or Russell’s cinema in general, this comes warmly recommended.

|