|

I have a feeling that the most commonly used phrase in my reviews of films that do not conform to the mainstream norm is “it won’t work for everyone.” This is generally me quietly reminding readers that what I have to say is just a personal opinion on a product of a medium in which all works are judged in that court, whatever claims might be made to the contrary. When reviewers claim that this film is great and this one is terrible, what they’re actually saying is that they loved this one but hated that one. There are no scientifically provable ways of defining the quality of a work of art, at least beyond its technical proficiency, and the likes of artists like Man Ray and Jackson Pollock forced a major rethink on even what that could really mean. And when filmmakers play with traditional form and structure, this can sometimes result in works that make for challenging viewing, precisely because they do not conform to long-established rules and expectations. That doesn’t mean I’ll like them, but I’ll certainly give the filmmaker credit for trying something that others might not even have considered. And when I do connect with such a film on any level, I know it’s going to be a tough sell to what a sizeable portion of even our readership. Can you guess where any of this preamble is heading?

In essence, Taiwanese director Tsai Ming-Liang’s 2003 feature, Goodbye, Dragon Inn, is a record of the final screening at a large but run-down Taipei cinema before it permanently shuts its doors. I will admit that this last bit of information is not revealed by the film itself until its final scene, but I can’t see that doing so here is going to act as a spoiler because it’s been stated in every synopsis I’ve seen, including the one on the cover of this Blu-ray release from Second Run. If you’re looking for a Taiwanese take on The Last Picture Show, however, you’ve come to the wrong film, as while there are indeed multiple characters to keep tabs on here, this is no coming-of-age story and there aren’t any real character arcs of note. Some will argue that the same could be said for anything approaching a story, at least in the traditional sense. But does that matter? Well, I’m coming to that.

Then there’s the editing, which doesn’t so much break with convention as completely disregard it and make up rules of its own. This is signalled early on when the audience at a screening of the 1967 King Hu martial arts classic Dragon Inn is observed through fluttering curtains from the rear of the cinema, presumably by one of the cinema’s employees, and the shot continues far beyond the point where it has seemingly served its narrative purpose. It’d get used to this, as it’s a signature aspect of Tsai’s approach here. The film runs for 82 minutes, yet I have a feeling that if the footage was handed to most editors to assemble without guidance from the director then the length would be shortened by about two-thirds. It’s also worth noting that not a lot happens during the course of that running time, at least in terms of on-screen action, and that the first line of dialogue doesn’t occur until just over 40 minutes into the film. A slow and punishingly boring experience then? Ah, well, this is where that opening preamble comes in. For some it definitely will be and indeed has been, at least if the more dismissive and even hostile comments I’ve read online are to be believed. And I’m sure those fervent dissenters will be shaking their heads in disbelief at the news that in a 2012 Sight & Sound poll in which directors were asked for their picks for the greatest films to date, Tsai Ming-Liang put his own film on his list.

If it seems as though I’m dancing around not just my own opinion of the film but what happens within it, you can put this down to the fact that Goodbye, Dragon Inn is not an easy film to start making even close to definitive statements about. I do, you see, get where those who dislike the film are coming from, and even I at times found myself quietly muttering “cut” during some of the longer held static shots. Why, I wondered on occasion, is this image being held on for this length, past when it has not only done its job but underscored it multiple times? Or had it? You see, despite a hesitant start, for me watching Goodbye, Dragon Inn proved an increasingly involving and ultimately seductive experience, as I gradually adjusted to Tsai’s approach and the film’s unhurried pace and found myself oddly intrigued by characters about whom I knew little and situations in which little is explicitly stated. And while I’m still not sure about the length of some of those long-held shots, I also warmed to the idea that there was a very real purpose to many of them.

Tsai clearly had no interest in telling a story per se, but instead focusses on characters and moments that open small windows into lives whose back stories we are then invited to expand upon ourselves. Central to this approach is a young male Japanese tourist (Kiyonobu Mitamura) whose actions and observations weave a connecting tread to some of the other patrons at this poorly attended swansong screening. He seemingly first enters the cinema to shelter from the rain, but once inside his attempt to watch the film is disturbed by the noisy food eating of the couple a few seats down in the row behind him. Here the decision to hold on a static shot of the tourist and the snack eaters serves a dual purpose, not only capturing the essence of a situation that few serious cinemagoers have not found themselves in a number of times, but also by gracing the situation with an unexpected layer of humour. Despite the rustling of plastic bags and comically noisy sucking and chomping, the tourist does his best to try and ignore the noise and watch the film regardless, intermittently turning his head to throw irritated glances that the snacking patrons are not even aware of. By the time he elects to move seats it occurred to me that I’d been watching this unfold in a single shot in real time, and that this was why it felt so familiar to me. I’ve genuinely lost count of the number of times I’ve fought to tolerate such a disturbance, and when my disapproving glares failed to have even the smallest impact I would often move seats to avoid a potentially unpleasant confrontation. Later in the film this moment is recalled and amplified when the ears of the re-seated tourist are berated by a young woman whose almost robotic snack-crunching is almost loud enough be mistaken for gunshots.

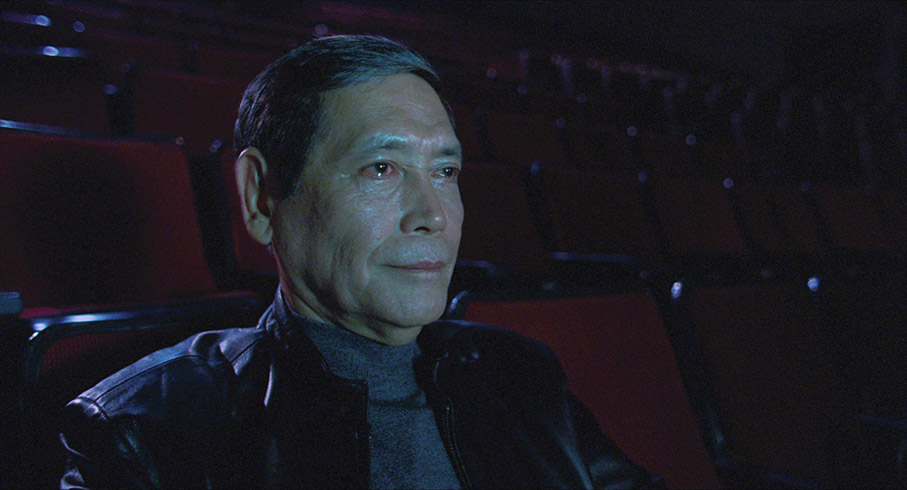

I knew little about the content of this film before sitting sown to watch it, but something about the timing of the men who slip out of the side door and return a short while later made it subtly evident that they’d not all drunk too much coffee before the screening and that the cinema had become a location for gay men to meet for casual sex. The interest shown by the Japanese tourist in this back-and-forth a few rows down from where he is seated also subtly suggests that he may have come here in search of such an encounter. This gives rise to an amusingly peculiar moment when the tourist, after repeatedly glancing at a middle-aged man a couple of rows down, moves and sits next to him, then turns to curiously scrutinise his face, an oddly rude inspection that the man elects to ignore until the tourist gives up and departs. There is, it turns out, a logical explanation for this (though not for how close the tourist gets to the man, which seems to be played more for comic effect) that is revealed only in the film’s touching final scenes. When the tourist does elect to venture through the side door through which he has seen other men pass, the almost labyrinthine collection of corridors and storerooms in which he finds himself has a disorientating, other-dimensional quality.

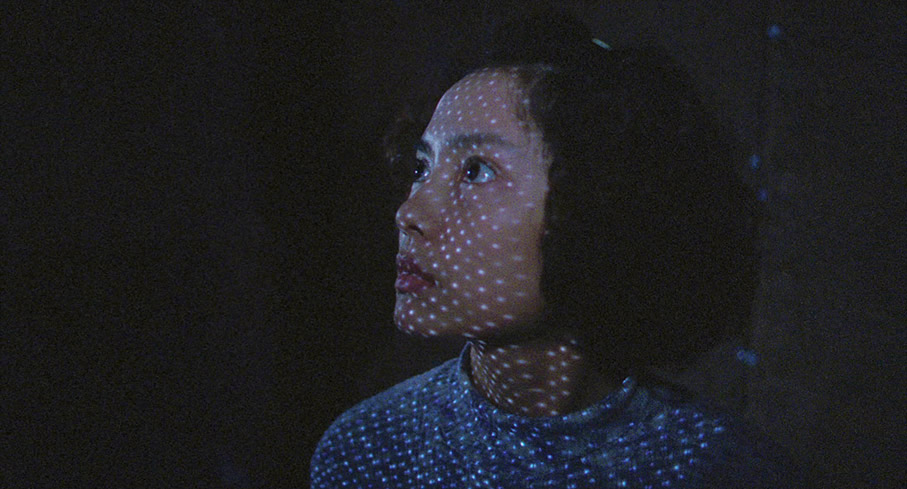

Similarly featured is the handicapped box office cashier (Chen Hsiang-Chyi), who is first seen as her other duties cause her to just miss the arrival of the Japanese tourist and is then observed at length tucking into a sizeable steamed rice bun, a piece of which she decides to give to the projectionist (Tsai regular Lee Kang-Sheng). For me, it’s here that the purpose of the lingering shots first really started to click. As we watch the cashier, her right leg supported by a metal brace, slowly limp her way in real time down long corridors and up stairways into what almost feels like the top of the world in the hope of being noticed by a man who seems barely aware of her existence, the impact of her handicap on her work and her personal life really hit home. As someone for whom walking has become a problem in recent years, I am perhaps more sensitive to this aspect and really felt for the cashier when her shyness keeps her from handing the cake to a man to whom she is clearly attracted. Instead she places it quietly in the entrance to the projection booth for him to hopefully find and gratefully consume, then slowly makes her way back to ground level. This extended sequence reminded me of Shindō Kaneto’s The Naked Island, whose wordless opening half-hour consists solely of a husband and wife carrying water from the mainland to the island on which they have made a home and up difficult pathways to the fields in which their crops grow. We only watch a single task being performed in real time during the course of the entire first third of this film, but it not only makes compellingly clear – in a way that no short montage could – how crucial the role of fresh water is to the couple’s existence, but vividly illustrates the hard work and dedication that is required to keep the crops that are their life and livelihood watered. There is one notable exception to Tsai’s meditative approach. In the only fast cut sequence in the film, the cashier is momentarily mesmerised by the fighting skills of the on-screen movie’s female action star Shangguan Lingfeng, the rapid back-and-forth cutting between the two hinting at the cashier’s dreams for life that fate has denied her.

It’s not hard to see parallels with the cinema of Béla Tarr, another filmmaker who favours lingering on images for far longer than conventional wisdom dictates, a technique that peaked in the seven-hour Sátántangó. I’ve no doubt that an argument has been made that if that film was re-edited to bring the shot length down to a functional norm then it would probably run for only a couple of hours. But then it would no longer be Sátántangó, just as doing likewise to Goodbye, Dragon Inn would effectively rob the film of its identity. If you watched it and felt nothing but exasperation, as some definitely have, then you’re probably thinking that this would be a good thing. I certainly experienced an initial uncertainty about whether I was going to be able to engage with a film that was unfolding as a series of long-held and only slightly animated tableaux, but just as I did with Sátántangó, once I adjusted to the pace and rhythm of Tsai’s approach I became completely absorbed in the small details and the half-told stories that are gently teased by the static camera’s unblinking gaze.

Goodbye, Dragon Inn feels in some ways like a tapestry of half-recalled memories triggered by the loss of the sort of movie palaces that some of us remember from our younger days, and yes, I’m including myself in that category. I’m old enough now to recall when even local cinemas were huge auditoriums with imposing screens, the majority of which were later subdivided into two or three smaller and altogether less impressive venues that offered more choice, but on a smaller scale. And while it could be argued that while up until the current pandemic put many of them at risk of permanent closure, cinemas in the UK were still attracting sizeable audiences, venues like the one in Goodbye, Dragon Inn (which was shot in a real cinema that was was on the verge of closure) that screen older movies for a specialist audience have become altogether rarer, at least outside of major cities. Watching the cashier make her way slowly up the steps of this cathedral of a cinema with its decaying walls and water-stained floors really does have a sense of sad finality to it, with the water that drips steadily through its leaking roof having the metaphoric feel of tears being shed by the venue for its imminent demise.

A final thought. As the cinema in the film closed its doors for the last time I was reminded of a trip I made to the district of Nakano in Tokyo in 2004, where a Japanese friend had booked me into a reasonably priced hotel that was located directly above a basement cinema that specialised in screening older movies. While there, I just had to pay this venue a visit and saw Fukasaku Kinji’s 1966 Hokkaido no Abare-Ryu – without the aid of English subtitles, no less – and was seriously impressed by the whole experience. There weren’t many of us in attendance, but the cinema was immaculately kept, the seats were comfortable, the screen was a good size and the condition of the print being screened was close to miraculous. As I emerged, I remarked to my friend what a wonderful resource this was to have so close to his home, to which he sadly responded, “I know, I love to come here, but not enough other people do nowadays and so it’s closing next month.” This is where the lingering shot at the end of Goodbye, Dragon Inn of the empty auditorium really hit home, acting as it did as a reminder that sometimes you really don’t fully appreciate what you’ve got until it’s gone.

Framed in its theatrical aspect ratio of 1.85:1, the director-approved 1080p transfer on this Blu-ray has been sourced from a new 4K restoration, and the results are rather splendid, with a nicely balanced contrast range and solid black levels that only soften a tad in some darkest scenes so as not to crush the shadow detail. Gven how much of the film takes place in the dark, the clarity of the picture and detail is really impressive. Colours are clearly rendered and detail is strong, and the image is clean of any dust or wear.

A Linear PCM 2.0 stereo soundtrack that I’m assuming is the truest to how the film originally played is partnered with a DTS-HD 5.1 surround remix. Both are in fine shape with a strong dynamic range and excellent clarity, but the DTS surround track most definitely has the edge, having a fuller and more expansive feel that really showcases the film’s layered sound design and making inclusive use of the full sound stage.

Optional English subtitles kick in by default.

Interview with Tsai Ming-Liang (35:37)

Conducted in Taipei City in 2020, this hugely informative and engaging interview with director Tsai Ming-Liang is a first-rate companion to the film itself. Tsai talks about the genesis of the project, the real-life cinema that both inspired the film and became the location in which it was shot, his childhood of cinema-going and first exposure to the films of King Hu, the film’s cinematography and sound design, the Japanese fan of his work who ended up playing the young tourist in this film, how he revised Chen Hsiang-Chyi’s interpretation of her role at the cashier, and a good deal more. He reveals that he set out to make a work of slow cinema and that it knowingly explores the concept of ‘the gaze’. He’s also not afraid to admit that his films tend to provoke critical debate about his talent, and even references a newspaper cartoon that mocked this film’s lack of commercial potential. This is an excellent extra that genuinely expanded my appreciation of the film itself, though it should be noted that the interview was shot outside and occasionally does battle with wind noise.

Pearly Chua in Madam Butterfly

Madam Butterfly (36:41)

An expansion Tsai Ming-Laing’s contribution to a project launched at the 2008 Lucca Film Festival in Tuscany in which twenty ‘experimental’ filmmakers were invited to make five-minute shorts to mark 150th anniversary of Giacomo Puccini. Using the composer’s most famous opera as its kicking-off point, the film is set primarily in a busy metropolitan bus station and focuses on a woman who is trying to get home but doesn’t quite have enough money for a ticket. Comprised of just three hand-held shots and only hinting at the narrative that led to her current situation (she has been away with a boyfriend who has gone home without her and left her to take care of the hotel and minibar bill), it was shot guerilla-style on what was likely a small HD camcorder. Its lack of narrative and home video aesthetic is likely to infuriate as many as it intrigues, but while I understand how easily it might frustrate, I nonetheless had no problem sticking with it and found myself speculating not just on the possible backstory for the the woman’s current situation, but on the very making of the film itself. When the woman approaches the ticket office, for instance, the angle chosen suggests the ticket seller was not in on the gag and was thus expected not to sell the woman a ticket because she is just short of the required fare, but when seller is encouraged by others to accept this lower payment she agrees, and a reason for declining this offer then has to be quickly manufactured, or at least that’s the way it seems. Interestingly, it’s also nigh-on impossible to watch the sequence in which the woman starts uncontrollably coughing in this busy bus terminal in the current climate without seeing it as an albeit unintended trigger moment for a story about how easily Covid-19 can spread in a public place from a single carrier. This film has fixed English subtitles.

Also included is a Booklet that features a fascinating essay on the film and its director by Tony Rayns, who also provides some useful background information (that I have cribbed from above) and assessment of Madam Butterfly, plus an appreciation of Goodbye, Dragon Inn by acclaimed filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul.

The very definition of a film that will starkly divide opinion, Goodbye, Dragon Inn is likely to prove frustrating and unsatisfying viewing for some, but if you can adjust to its slow pace and fascination with stillness and small moments, then there’s a good chance it will really work for you. Given my initial uncertainty, I was surprised how involved I became in it and ultimately how much I gleaned from what is only suggested by what occurs on screen, and was certainly caught out by its poetic evocation of childhood memories, its moments of almost absurdist humour and its touching final moments. Nostalgia for the cinemagoing days of my youth certainly played its part here, but if the film also works for you then the quality of the restoration and transfer and the Tsai Ming-Laing interview make this Second Run Blu-ray an easy recommend.

|