| |

"That film, I thought, was one of the very rare American films that I would compare with the serious, intelligent, sensitive writing and filmmaking that you find in the best directors in Europe. It wasn't a success, I don't know why; it should have been. Certainly I thought it as a wonderful film. It seemed to make no compromise to the inner truth of the story, you know, the theme and everything else. Really magnificent." |

| |

Stanley Kubrick, interviewed at home in 1980 by Vicente Molina Foix |

I have been contemplating this review for about eight years now after getting hold of the only incarnation it used to exist on back then, a DVD. Remember those? It was a film I saw in my late teens in the cinema and as it wasn't released theatrically in the UK except for a brief 2021 re-release, I must have seen it on my first trip to California in 1979. I was so struck by it as an 18 year-old that the actors became locked and loaded into my mind and every time any one of the main cast appeared in another movie, I always used to simply smile. Stanley Kubrick was an entrenched Warner Brothers asset and Warners distributed Girlfriends and no doubt a 35mm blow up to Stanley himself. That's a guess but it seems logical. Bless you, extra features. Oh, it's so much better than logical. Director Claudia Weill says in her interview that Kubrick either requested it or it was sent to Stanley by Warner Brothers. The great man then invited her over to meet with him in Childwickbury, Hertfordshire. They spent two days together prompted by Kubrick's admiration of Weill's achievement. Well, I have not seen the film since my DVD viewing eight years ago and I'm not 18 anymore but joy of joys, it was restored on Blu-ray in 2020. Did I miss a news item? I would have pre-ordered and tapped my fingers frustratedly until I could hear my collies bark their hearts out protecting the house from our postman. Well, it drops tomorrow and I cannot wait.

Here are some words that conjure up intense excitement in me; Independent filmmaking, New York, the 1970s. Altogether, they promise potential, evoke rabid enthusiasm and a love for an art form that has clutched me tightly ever since seeing my first movie. I am not going to be able to keep myself out of this review (not that we ever try to at Outsider) but Girlfriends is special partly because I felt at the time like I was the only one who saw it. The reviews were very good but, of all things, there was a newspaper strike in New York City on its release which had director and star handing out fliers advertising the film outside one of the cinemas showing it. Girlfriends never stood a chance. As Father Ted and Dougal might of said, "Up with this sort of thing!" But this little gem got BAFTA recognition, festival awards, accepted into Cannes, Warner Brothers saw enough in it to give it a distribution, the great Stanley Kubrick championed it and to blatantly steal from its Wikipedia page, "In 2019, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant." Amen to that.

A brief synopsis; Susan Weinblatt, a promising professional photographer, shares a small apartment with Annie Munroe, a budding writer in the late 70s in New York. They have a very honest, platonic relationship which is not without its tension and sharp edges. It's suggested, by Annie reading her work to Susan while she's in the bathroom late for work, that Annie doesn't have the talent with words that Susan has with images. Susan makes a meagre living taking bar mitzvah and wedding photographs. Happy to have sold some artistic photos at last, she shares her joy with Annie who then drops a bombshell. She's getting married and she's therefore moving out. Susan's life then spirals from one small setback to another as she tries to find some equilibrium. There are a few dalliances at romance, money worries and relationship woes and resets but the film essentially lives up to its title. This is a woman's movie about women's relationships and probably one of the very first of its kind, which is almost shameful seen from a certain perspective.

Director Weill used to wonder about the perfect heroine's sidekick in movies she was brought up on. She observed that she was usually less attractive than the star (of course) and often 'ethnic' which I'm assuming in this case means Jewish. She desperately wanted to see that girl up on screen and experience her life. So Weill and friend (and writer) Vicki Polon came up with the story and Polon delivered the script. It is an excellent piece of work for what's not said, merely subtly implied but the dialogue is of a particularly high standard too. Just have a look at this. Eric has just been introduced to Susan at a party. Susan is somewhat pre-occupied with Annie gone. Apart from introductions, this is Eric and Susan's first conversation…

| Eric: |

So, would, would you like to... Dance? |

| Susan: |

No. |

| Eric: |

So, you're of Chinese ancestry, huh? |

| Susan: |

Wrong. Japanese. |

| Eric: |

That's what I meant. Japanese, yeah. |

| Susan: |

Oh. |

| Eric: |

North, right? Northern Japan? |

| Susan: |

No. |

| Eric: |

South. |

| Susan: |

No. |

| Eric: |

North. |

| Susan: |

Yes. |

| Eric: |

Yes. That's what I meant. |

Now, some of you may be scratching your heads wondering why this meandering nonsense is so noteworthy to me. If there is some New York based cultural meme that suggests Chinese girls don't dance which I am unaware of, then I hope my reading still holds. I didn't get it the first time I saw the film or I would have remembered the exchange but my antennae are a little more attuned these days. This is the exchange of two smart and wary people simply having fun. "So, you're of Chinese ancestry, huh?" is, believe it or not, a superior knock on the compatibility door. He's testing the waters, saying something frankly ludicrous to see if Susan will come out to play. The, dare I say 'normal' response would be "What? No. Why would you say that?" and the game is up. Susan is clearly Weill's 'ethnic' character and so obviously has no Chinese genes to speak of. But look at her answer, "Wrong. Japanese." That is the equivalent of opening the door once it'd been knocked on. Now they both know the rule-less game they are playing and the absurdities and contradictions pile up. It's also beautifully played but we'll get into the acting a little later. When a fellow photographer Julie stays at Susan's apartment and Susan returns after an argument with her boyfriend, Julie asks "What's the matter?" Susan replies "Everything," and to her immense credit (and thank you screenwriter Vicky Polon) Julie replies "Is that all?" I'm sorry folks but I am a sucker for smart writing.

The first thing to notice after repeated viewings of the film and the extra features, is Weill's company name… Cyclops Pictures. Given that she was rarely seen on any previous project without a beloved camera pressed to her face, the monocular company name seems foretold. On her Chinese trip filming with Shirley McClane, her Chinese hosts asked her repeatedly to put her 'baby' down and join them… They had a point. Anyone who's been on holiday and agreed to be the unofficial chronicler of said holiday has experienced that odd detachment from the 'present' with a camera attached to your face or an iPhone at arm's length. The second thing that actually shocks you (it also successfully cements the film in to the 70s) is that everyone, or almost everyone, smokes. There're smoke trails snaking north in almost every scene. It's not important but it was a shock given the almost pariah status of smokers in 2023. Oh, and let's hear it for denim. If product placement was a thing, the Levi-Strauss estate would be more than pleased. There is also in this film the most justifiable and natural nudity you will ever see. It's an organic part of the characters' inter-relatedness. If Susan is trying to slip away from a one night stand, there's no self-consciousness in her getting dressed even if nudity is glimpsed while she does so. It's just – to overuse the word – authentic. The hitchhiker who makes very overt passes at Susan is seen naked but it never, ever feels salacious. That’s the male gaze and its tendency to over-sexualise what may be utterly natural to a filmmaker with a different eye and point of view. Director Weill doesn’t exploit her actors, she observes their characters. Both Susan and lover Eric are captured naked in a long shot and there is nothing pornographic about their coupling. It’s a relationship in action not pornographic inaction.

There are many creative aspects of the film worth noting. The 'red wall' transition is justly hailed. Annie moves out and Susan is left with an Annie shaped hole in her life so moving in to her new apartment she starts painting a wall, its vivid colour signposted earlier on. Of course, there's a huge circular crack in it which she valiantly tries to paint over. It's not the most subtle of metaphors but you have to take them when they present themselves. The sound of her best friend's wedding guests is folded over from the photo montage wedding (a cheap and effective way of eliminating the need to shoot a bound to be expensive wedding scene). It's been said many times but often creativity's very best friend is limitation. If you can't afford to do A, do B in some style. One tiny aspect that made me grin also places the film historically. One character gives out their phone number. Big deal, right? Without the bloody '555' that filmmakers were obliged to tack on to any number in case someone called the number and harassed a real person*. The two art gallery characters, Beatrice and her assistant both wear foam neck braces. My first response to that was they may have been in a car accident. Weill states that there was some sexual behaviour that also caused the same injury. I'll leave that one to your imagination because mine drew a blank. Another aspect of Susan, the lead, that bonded me to her was that she developed her own film and printed her own photographs. The present generation have no knowledge of the effort and expense that this took, nor should they. But I remember it all too well and still recall that flush of excitement as an image appeared submerged and gently agitated in the developing fluid in the red glow of a darkroom reeking with chemicals. I can still smell them.

Before we get to the actors, let's acknowledge the more weighty and pertinent themes that the film was taking on. To quote Jack Thorne's superb line of dialogue from Enola Holmes, underlining the idea of white male privilege; Edith, a black female martial arts instructor, chides Sherlock Holmes for being uninterested in politics. She offers a reason for this… "Because you have no interest in changing the world that suits you so well." Well. Said. We can apply that to a majority of men whose world was – and still is to a degree – a man's one. Unique to their sex, women have to make specific choices which affect their lives in profound ways buffeted by an indifferent world. Things have come a long way in certain societies from the woman/wife in the homemaker and baby raiser role and that is as it should be. But up until Girlfriends, Hollywood had never examined female friendships in quite this way.

A small but relevant tangent… Do you remember those fellow kids in school who seemed to have coolness thrust upon their shoulders, charisma by the ton, stars that we mere planets revolved around? Forget school. I have close friends today, two in particular, whose existence outside of our get-togethers live imagined lives of stunning fullness and excitement which I envy. How can anyone envy a life they have themselves imagined for someone else?! Isn't that the essence of stupidity? But I still do it, create a narrative for them and inevitably gift them lives far more urgent and compelling than mine. There's that ache in both friends in Girlfriends that while apart, they are imagining each other being happier in another's company or having success they could not have achieved while softly shackled in their co-habitational friendship. That ache is at the heart of those choices women have to make and to decide crucially when to make them and it's also the very DNA of the movie.

OK, let's get to the extraordinary performances. And trust me. To be this authentic, you have to be extraordinary. Acting is quite the art. You have to worship at the altar of believability while standing out which runs the risk of shaving off layers of believability. You have to not act but be. A classic example of acting you cannot take your eyes off is Heath Ledger in The Dark Knight. But was he believable as a deranged, psychotic criminal mastermind. Well, yes. The mere idea that director Christopher Nolan let Ledger's performance direct his own direction is a testament to the actor's work. But what we have in Girlfriends is total authenticity born from a core of emotional truth teased out by screenwriter Polon and director Weill. Melanie Mayron is a total revelation in this film. Susan is achingly real. We feel everything she feels, perhaps even at a greater intensity than she does because she channels her character so well. It's almost as if no one told her she's being filmed. I suspect she may still not realise there was a camera in front of her. It's also a very deft comic performance. Her irony is honed and sharp and while I wasn't moved to laugh out loud at certain moments, I smiled a great deal watching Mayron respond so honestly to all the travails her life threw at her. When she occasionally wins, it's such a delightful experience until her own cultural upbringing asserts itself and she starts to doubt herself. That's when you just want to hold her and say "It's OK. You are actually allowed to be talented."

The rest of the cast are also noteworthy. Even though Weill doesn't judge her characters, there's no doubt in my mind (other minds are available to offer doubt) that Susan's best friend Annie (Anita Skinner) plays the most unsympathetic character. She's not the greatest writer in the world and very frustrated when her best friend confirms her own insecurities and even in a marriage to a man we assume she loves, she's often shown in a frustrated light. In jest, her husband belittles her and she takes it badly (fair enough). She is writing and yet the crawling horror of an attention seeking baby snatches her focus away from the page. OK. It's her own child but our children can be frustrating at times. Her own honesty often cuts to the quick and despite best friend status, she is quite merciless to Susan when she's at a low ebb. Quick aside… I tried to find out why Anita Skinner moved on from acting. I found a web page listing saying that she moved into real estate, wrote poetry and "her work as a photographer…" Dot, dot, dot… and there the listing was frustratingly incomplete. The web page it pointed to had no more details. But I did enjoy the idea that Anita might have excelled in the job more than her fictitious flatmate was fêted for in their own movie.

By far the biggest name in the cast list was Eli Wallach as Rabbi Aaron Gold. I'm so used to associating him as the 'ugly' in the Sergio Leone classic, The Good, The Bad and the Ugly that I'd forgotten what defines a good actor, the ability to be believable in many diverse roles. Wallach here is not a broken man but one who yearns for something beyond his home life and finds it in a girl who, perhaps not entirely seriously, wanted to be a rabbi herself and someone who values his loving attention. Apparently Wallach was thrilled to be a romantic character whose feelings for Susan were very real until his commitment to his family doused those flames. 6 years before This is Spinal Tap and 9 before his villainous turn in The Princess Bride, Christopher Guest was, presumably a jobbing New York actor. He caught Weill's attention for "not giving a shit" and answering her question "Are you SAG?" – the Screen Actors Guild currently still on strike – with the disarming reply "No. I'm quite happy actually." He was cast on the spot. His scenes with Mayron are a delight, a micro-glimpse into how males and females can set up and set off the most ridiculous arguments that at the time are mere steam from cracks created by other psychological catalysts ungraspable to those that experience them.

And then there was an actor who had privileged me with a behind the scenes look at a film that had affected me profoundly, Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Bob Balaban as Martin, the man who lured Annie away from Susan, published his diary on the making the of the Spielberg film and so had bonded me to him and his work. An actor of rare sensitivity (and a director with a terrific but little known domestic horror to his name, Parents) who in Girlfriends is presented without judgement but is regarded as a bad guy of sorts for splitting up a perfectly good friendship, he redeems himself continually by confounding expectations. His efforts at learning Italian turn the character around in the eyes of the audience (or this audience for one). His turn in Altered States still impresses mightily. Finally, I must mention the hitchhiker, Amy Wright as Ciel (aka Cecilia). I had to reach into my furthest memory caches to suddenly twig where I'd known this actress from my film going. In the utterly wonderful coming of age tale, Breaking Away, she was of course, Moocher's girlfriend and wife to be Nancy who had to split the cost of the marriage certificate with her young prospective hubby-to-be. That was in itself an unforgettable performance, so natural and easy. She's just as good here.

Fred Murphy's cinematography is unfussy and presumably complements Weill's own style. If you are a cameraperson, with quite a few years of experience behind you, and you migrate to direction, are you open to collaboration with your cinematographer? I can't imagine Weill being uncollaborative. Spend five minutes in her company via the extra features and you'll know she couldn't possibly be. There are expressive angles mitigated one assumes by literal tight spots but that's what gives the film part of its identity. I'm assuming everything was shot in real locations which gives some of the interiors a slightly murky feel with 70s' film stocks not really as sensitive as they are today but that's never an issue. Michael Small's sparse score nails its ethnic colours to the mast over the photo booth opening titles. But there are few cues included that don't specify the religious identity of the protagonist but instead underscore the emotion. It's an understated musical score but very effective.

Oh, hell. I cannot be remotely detached from this extraordinary film. It's imperfect in many ways which just adds, paradoxically, to its honesty. Stanley got it right and, oh boy, so did Claudia, Vicky and Melanie. Bravo.

The difference between the DVD and the Blu-ray is astounding. Most of the dirt, dust and scratch damage has been smartly erased. Presented in the 1.66:1 aspect ratio, giving you thin black bars either side of a 16:9 TV, the one aspect of the film that the restoration could do little about is inherent in the recording medium, 16mm film. Wonderful, gloriously grainy 16mm film. I have a soft spot for the stuff having joined the industry before computers muscled into post production in the early 90s and 16mm was ubiquitous in BBC Film Units across the country. In the booklet it does mention 'noise management' which in film terms means grain. Film stocks got significantly better over the years but 16mm stock in the 70s guarantees grain that a higher resolution presentation format would show off effectively. And this is from a 4K scan presented in HD. And here it is, unashamed in all its glory. There are focus issues in one of two spots (independent filmmaking, remember?) but we don't need to worry about those. But the rule is, the darker the environment, the grainier it gets. Young people may not realise how many lights film required 45 years ago, having phones in their pockets that can shoot without lights and still get pleasing results.

The original Mono soundtrack has been restored and there's no problem with understanding all the dialogue. The hiss is minimal as in my two recent viewings, I didn't notice it at all. There are subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing.

Claudia Weill (26' 46")

"Making films is reaching out to other people in the world. And it's a great adventure." This is the best filmmaker interview I think I've ever seen. Weill is wise, erudite and, in her seventies, still utterly in love with filmmaking and it radiates from her like a veil of enveloping warmth. There is not an aspect of her life she describes that isn't vital, hugely absorbing and utterly compelling. I'd sacrifice quite a bit to cut a film directed by Claudia Weill. Her insights into documentary filmmaking are so on the nose, you can breathe them in with no effort and she's not shy about serendipity and taking full advantage of those lovely happy accidents. Of the red wall I mentioned in the review, she says "Metaphors kinda appear in front of you." Being accepted at the Avant Garde Film Festival in Rotterdam, she says "2,000 people in the audience! And they're Dutch! And they're laughing!" She mentions her teaching career and drops the most wonderful insight by turning the experience on its head; "…because I learned so much!" she said. This is a glorious filmmaker still fizzing with all the zeal of youth, a role model for women to be sure but also very, very human. Bravo.

Girlfriends: A Look Back (16' 00")

Deep in Covid time, three of Girlfriends' principals and the director share a Zoom call. Weill chats with Melanie Mayron, Chris Guest and Bob Balaban. I would imagine the call would have gone on a little longer than what we're offered but it is a lovely thing to see all four of them together. I'll not spoil the content because it's nicer if you go in cold. Bob Balaban doesn't get a lot to say but I think it's safe to say he was glad to be in everyone's company as was I. The film was a special experience for all concerned. Just to add a tiny detail… There's the old canard that says the three things you should spend most of your money on are shoes, a chair and a bed because you spend your entire life in each of them. And I have to say Weill has exquisite taste in chairs. The most comfortable I've ever sat on I discovered while doing a job in London decades ago. It was a revelation as I suffered then from tension-knotted shoulders. Two or three days later, working while sitting in a Hermann Miller Aeron chair, that tension eased off. When I discovered the price the tension came flooding back… But if you can afford one, they are immensely kind to your posture.

Vicky Polon (12' 32")

Polon started working recording sound with Weill on camera. There was an itch to direct a feature. The two started working in what she calls a 'net' and the world didn't exist. The modern term is 'bubble'. I know what that's like. Emotional truth was the highest priority. Polon actually speaks out her dialogue, inhabiting multiple personalities performing the characters. She offers the axiom "cut out early and come in late…" something screenwriter William Goldman espoused often in his classic Adventures in the Screentrade. She channels Orson Welles' story about starting his career figuratively walking along the edge of a cliff. His ignorance about the industry (the metaphorical risk of falling) meant that anything was possible. Orson's 'anything' was Citizen Kane made at the ridiculous age of twenty-five. Polon admits that now she knows making independent films is impossible (!) but when you don't know that, anything is possible. She is astounded that the film has lasted and credits its emotional honesty for that outcome. Polon is a terrific interview subject and it's not that hard to see how Weill and Polon became friends and creative partners.

Claudia Weill and Joey Soloway (22' 13")

This is two generations coming together with the connective tissue being Girlfriends. Joey Soloway produced the rather brilliant Six Feet Under and the Amazon series Transparent which netted her two Emmys. It's another Zoom conversation, lively, revealing and entertaining. Jean Luc Godard is namechecked as an influence on Weill, the risks and creativity of the now late French filmmaker inspired her to be free and not to conform to what movies up until that point were supposed to be. They chat about serendipity and subconscious creativity. They touch on the Jewish connection, dismissing the stereotypes. There is a lovely story about Weill showing her orthodox Jewish grandmother the film and she complained (kvetched?) that the subject should be Annie not Susan, the Jewish character… Even within the faith, Jews 'other' each other. Fascinating. We get the skinny on Weill's experience with Ray Stark – not great – and how the rules were so different for women in the 70s. Weill is as full of wisdom here as she is in her standalone interview and Soloway is appreciative and herself enlightening. This is a great chat not only about filmmaking but life if I can be (as they are) so bold.

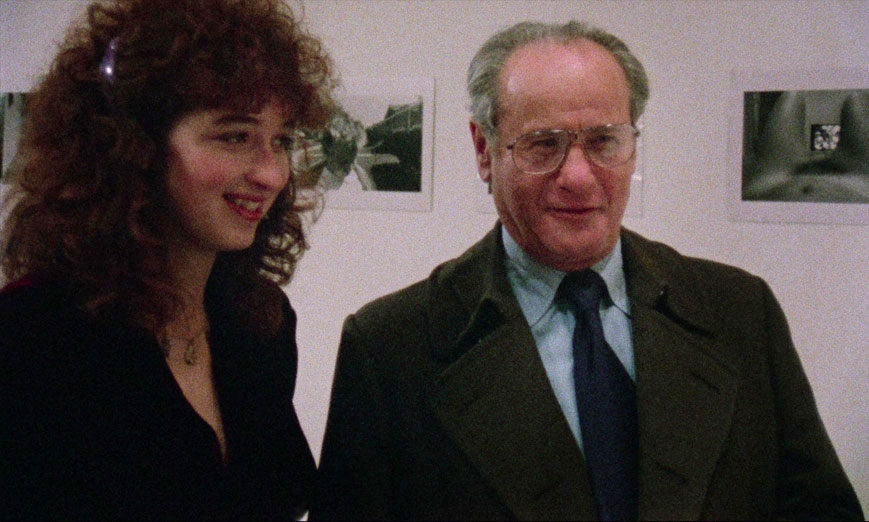

City Lights (19' 49")

This is an edited down 1978 Canadian talk show, hosted by Brian Linehan and features director Weill and star Mayron. Whether this was because it was edited this way or not but oddly, we never see Linehan's face. He's always presented from behind on the left and you're lucky if you get a glimpse at the tip of his nose. But he's not the focus here. Melanie Mayron seems a little nervous but Claudia Weill is (as expected from seeing the other extras) intelligent, focussed, confident and honest. The most startling revelation for me was Melanie Mayron admitting that no one had sent her any scripts after Girlfriends was released which stunned me given the strength of her performance. All I can conclude is that there was such a dearth of strong female characters being written at the time or that too few people had actually seen the movie. Both speak of it as if it was successful. I can find no box office figures from its original distribution and I accept it was noticed, won awards and got critical acclaim but it didn't break out. It's disheartening to realise what might have been the abyss-like depth of indifference to one half of the human population. I'm not going so far to say that anyone who didn't see Girlfriends is a misogynist. But women were second class citizens in the 70s and it's depressing that the separate feminist waves are still hitting the same patriarchal rocks in the extremely sensitive culture we find ourselves in today.

Joyce at 34, a 1972 short film by Weill and Joyce Chopra (27' 49")

A very intimate portrait of a woman seemingly held to ransom by her pregnancy, a condition that stops her from going to work as a filmmaker. Weill covers the birth from the most intimate angle – full on - but the emotions on display are so genuine that the gore covered baby's emergence is not too difficult to watch. I particularly liked Joyce touching the arm of one of the doctors present. I suspect in hindsight that he was probably her husband all kitted up. It's quite something to see on a 4K TV, about as in your face as it can be. This is Weill in her comfort zone, chronicling the female experience. It's very moving and can conjure up even this male's memories and emotions at the birth of his own son. The voice over and sync are a little muffled, to be expected I guess but the 16mm film holds up very well. There's a charming flashback to a dance when Joyce was sixteen years old. In the 50s in the US, home movies were shot on 16mm. Despite its age, even those flashbacks are vibrant and alive. We get the family history and during a vigorous exchange of views on being a woman in the 30s and 40s, we get the impression that again, Weill was at the right place to document these histories.

"Whatever I do will be wrong," bemoans one of the women faced with the choice of staying at home looking after the baby (bored mum, not good for the baby) or going to work (coming home tired, also not good for the baby). The man's role is not ignored as we get a short interview with Joyce's husband and how his role changed after the birth. And, is that director Irvin Kershner with the pencil? This would be a director in a meeting with his writer, Joyce's husband, who's tending to the baby at the same time. "If I don't have her with me then I can be a person again…" is a very telling line from Joyce. Men rarely have such considerations to tie themselves in knots over. There is an image that sums up the idea being addressed here. How do you have a career in film (or any career) with a baby to look after? It's so difficult. On Joyce's lap at the Steenbeck (a 16mm editing table) baby Sarah has to taste the machine. What is it with babies experiencing everything with their mouths? Joyce comes to the conclusion that if her mother loved her as much as she loves her own child then her mother must have suffered a lot. Joyce at 34 is a revealing and illuminating light shone in the darker corners of the 'joys' of motherhood and it is very effective and emotive work. Oh, and I do actually miss hairs in the gate.

Commuters, a 1973 short film by Weill (3' 41")

A rather smartly edited short, presumably shot on colour stock though you'd be forgiven for thinking there'd been a sepia filter applied, this film looks at the arrival of New York's white male workforce at a suburban train station, jostling for platform position and getting on the train presumably bound for Manhattan. In one long shot the music changes from a kitsch 50's string-led instrumental which gives the men a jaunty air to a heavier guitar blues vibe as another train arrives from the opposite direction from which black women wearily step off, climb the stairs and go out presumably to work in the unforgiving New York winter. On first watch, I thought it was one shot but there's a sneaky dissolve at about 2' 05" in. I'm sure there's a strong political point to be made here but I'll let you decide what that might be.

Booklet

After a double page of the principal cast and crew credits, we come to "Second Births" by Molly Haskell. She introduces the idea that second wave feminism granted women choice over their lives, eschewing the path well-trod of courting, marriage, motherhood and subservience to a man. She examines Weill's past work leading up to Girlfriends and throws out many other women filmmakers' names that I am not happy to reveal that I've not heard of. She charts Susan's journey with many more (and more pertinent) insights that I've gathered together in this bulging review but then her lens is cleaner and leaner than mine. Mine is clouded with empathy without real understanding. It's a beautiful essay packed full of wisdom and an absolute pleasure to take in.

"Fantastic Light" by Carol Gilligan is another eye opener. With just the first two lines of dialogue in the movie, she's attached Shakespeare and The Tempest and has comparisons to Miranda asking Prospero what he's doing and being told to essentially go back to sleep. If Gilligan came upon this glorious reference because of her own education, then bravo. I'd love to get scriptwriter Vicky Polon's take on it and even it's a coincidence, it's a sublime one. The idea that Weill has managed to shine a light on areas of female relationships that precious few in the visual arts had managed or alluded to before is striking. The examination of female motivation in this essay is reassuringly contradictory. Again, I am not genetically qualified to speak authoritatively on these issues but I do love reading about them. Girlfriends, without me being aware of it, has opened my eyes to the female experience and how complex certain aspects of being a woman are. If the movie, in this lovingly curated Blu-ray does nothing else, it should educate men and comfort women with the idea that there's at least one filmmaker out there who can communicate the very essence of what concerns her own sex. Long may her work illuminate all our understanding.

Girlfriends impressed me enormously when I was 18 but then I was probably too inexperienced to understand why. When I caught up with it again on DVD at the advanced age of 54 after many VHS viewings, it still impressed. Eight years on, the work still glows in my library of film as art, film as emotional truth, film as enlightenment. Hats off to director Claudia Weill, whose wisdom and engagement I could learn from forever, screenwriter Vicky Polon and actress Melanie Mayron who became famous for her work subsequent to this landmark film but gave a performance of such raw authenticity and honesty that I am still moved by it to this day. If you have anything close to my own sensitivities and taste, then this is a movie for you. Hugely recommended.

|