| |

"Georgy Girl was part of the trend in which British cinema shifted the focus from provincial life and back to the metropolis, celebrating new freedoms and social possibilities. Narizzano, influenced by the French New Wave and his chic contemporaries Richard Lester, John Schlesinger and Tony Richardson, explored such "shocking" subjects as abortion, illegitimacy, adultery and sexual promiscuity with a light touch.” |

| |

The Guardian's Obituary for director Silvio Narizzano, 2011* |

My sincere apologies for this way overdue review. My paid work rate suddenly flared up and we ran into Christmas and well, you know. More apologies if the ridiculous title to this review is meaningless to you. Unless you are as old as I feel, you won't know who Mary Quant is and why her clothing designs were as emblematic of the 1960s as the Beatles were. The following lyric is woven throughout my pre-teen life almost as much as the Thunderbirds' 'Dun du-du-duh' main theme. "Hey there, Georgy girl. Swinging down the street so fancy-free. Nobody you meet could ever see the loneliness there inside you…" Written by the Carry On star (and Harry Potter US audio book voice artist) Jim Dale and performed by The Seekers and sung by Judith Durham (a Jennifer Lawrence lookalike in her youth) with a near-as-damnit perfect voice, the song zoomed past 'catchy' over fifty decades ago. This is the king of the ear-worms and if the song wasn't so damn nice and folksy, I'd probably resent it but no. Its movie lyrics (carefully altered for a single release back in the day) are actually pretty dark but that melody could soften an audiobook of Mein Kampf. So it's a thrill to be finally seeing the movie it was written for and a bigger thrill to find that said movie works so well.

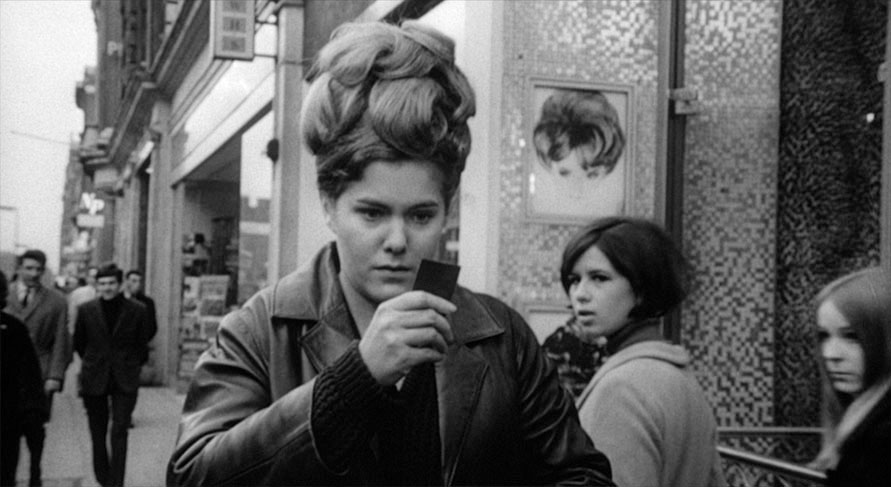

In the mid sixties, as London was starting to swing (whatever in God's name that meant), Georgy is a down dressing, 'plain', slightly overweight and normal young woman. She's hopelessly awkward, spends money on ridiculous hair dos that she then washes out as soon as she can find a public loo with a sink, and returning home, this dowdy Bridget Jones transforms in the company of the right people – children, natural, honest, non-judgemental children. Revelling in creative play and the abandonment of all of her insecurities, she leads a group of pre-teens in many creative exercises. If you see this scene, imagine what it would take to re-educate adults to have as much honest fun as these children are having. I think that Sir Ken Robinson was oh so right when he said that we are educated out of creativity. Google his TED talks and get great insights on education. It's clear that every one in the room is having such a great time. I knew from this early scene that I was on Georgy's side and whatever hurdles she faced, I'd be supporting her. To make matters worse, her father, who is trying hard to make his own daughter live up to his own narrow definition of womanhood, underlines Georgy's outsider status in the family. In an utterly charming and disarming moment, she undercuts his efforts and merrily takes the piss out of him with an extemporaneous medley of different tunes on the piano, a playful soundtrack to her father's pomposity. We then move through her dealings with stunning but stupefyingly selfish flat-mates, flighty boyfriends and sugar daddies until she chooses to accept herself on her own terms and gets her way, of a sort. The ending of the film is somewhat contentious but I won't be spoiling that here even though it's worth a 'sexual politics themed paragraph' all of its own.

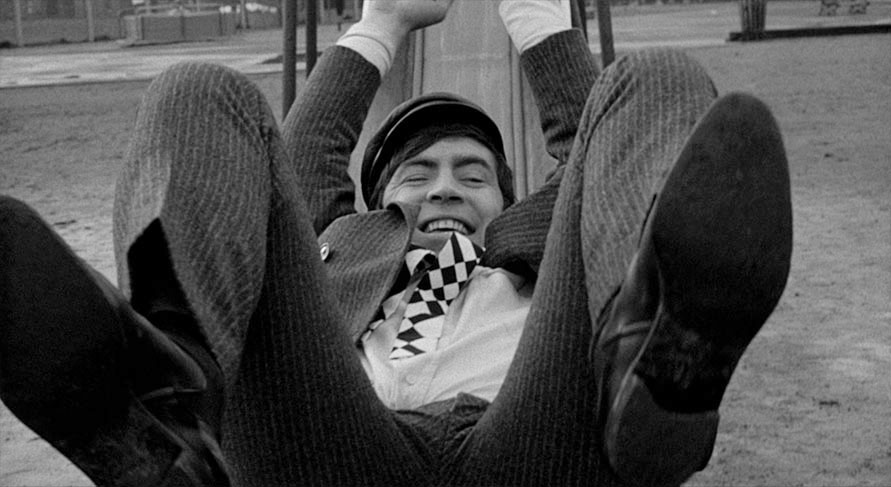

The actors are all having a ball. There is energy in the film that the cutting maintains but with such exuberant performances, it's sometimes necessary to slow things down a bit. Lynn Redgrave winningly plays Georgy in a role that almost defined her entire career. It's a tough ask for any actor to play dowdy. The entire film of The Devil Wears Prada was almost scuppered by asking a rational audience to accept that actress Anne Hathaway was a frumpy, unattractive mess. OK, with a fully coiffured Emily Blunt playing the beauty game next to her, the filmmakers were obviously trying their best but it takes a little more than a grey pullover to mask the evident appeal of this oddly maligned actress. Redgrave, whose more famous sister was first approached to play the role, found herself personally affected by it. In the movie she shares a flat with Meredith played by a frankly stunning Charlotte Rampling (I'm smitten, apologies) in her second credited of four roles thus far in her career. She was twenty-two and again, 60's London iconography would be the poorer without her participation but I'm not sure as a professional violinist she could afford all those Mary Quant designer outfits. She is very much cast as the opposite of Redgrave's Georgy but she's also pretty nasty. A good-time girl who seems over burdened with selfishness and self-regard, she was the perfect 'Heather' of her day. In fact, she could be regarded as the original 'Heather' albeit alone in her 'Heatherness' without obsequious acolytes. In short, she's a cast iron 'not nice' person. The word almost rhymes with 'beach' but I still can't use it with any confidence despite the fact I can label a man behaving badly as a bastard without breaking a sweat. Rampling's Meredith is everything self-serving about great beauty, the absurd idea that you win a genetic lottery and so automatically have carte blanche superiority over other people's feelings and needs. The best you could say about her is that she's always honest. Post birth, she's stunningly vile about her baby and about as unpleasant as a human being can be without committing actual violence. In between the two flat sharers exists a character, Jos, (an attractive if extra-fidgety Alan Bates) whom I uncomfortably recognise as too damn close to someone I know all too well. That constant need to be the centre of attention, that inexhaustible energy and surface charm that sends him to a children's playground briefly in love with the idea of becoming a father, riding a roundabout and then sliding down a slide and as he literally falls to Earth, his reality is sharply emphasised by a short gaze into a future he suddenly re-evaluates in the blink of an eye. He sees a stern man looking on disapprovingly with two young children (expertly cast). That's not the fatherhood he's looking for.

First billed is James Mason as the businessman James Leamington with a Rolls Royce and the dubious honour of being the first on screen character to my knowledge who openly grooms a young girl with the blatant ambition of seduction. James is decades older than Georgy. He's aided in this rather sordid desire by his butler who happens to be Georgy's hypercritical father. Played by Bill Owen, a few hundred miles from his most famous character, Compo in BBC TV's comedy flagship Last of the Summer Wine, we get the sense that Georgy's father, who dotes on Mason's character (more than is psychologically good for him) is severely conflicted. He wants Georgy married off but to his older boss? Mason, who took a drop in salary because he loved the story, plays the role with his original northern accent. It's a fairly dark part to play but Mason performs it admirably. There is a sense that he's going to pay for his interest in the younger woman by having to acquiesce to her desire to be a mother to someone else's unwanted child. This is given metaphorical weight by the pram he's forced to push up a staircase, helping Georgy prepare for her new arrival and the hordes of children he tries to navigate through on another staircase as they swarm from Georgy's drama class.

The film is full of small but potent gems. Planned or not, as a funeral line of black vehicles pulls away from the church, a dog on the right of frame sits impassively in the road and despite the roar of engines and close car movement, it stays defiantly put. At a registry office, Alan Bates lets two women in and then promptly walks into the door frame, a bit of business that would have seemed like the character just showing off but it's cut away from so smartly that we might give Bates the benefit of the doubt and think this to be a genuine moment of confusion. At a few minutes over the hour, editor John Bloom experiments with intercutting ever-decreasing timings of big close ups to indicate a spiral of potential intimacy. It's extremely effective, just one of Bloom's many contributions to the film not planned in advance by the director. This is why your editor has to be your best friend if only for the length of post-production.

I recently took delivery of an entire collection of the BFI's Monthly Film Bulletin from 1965 to 1991 so it seems a crime not to look up how this august organ reacted to Georgy Girl at the time. The specific publication, costing all of two shillings (10p at the time of decimalisation) but more like £1.67 in today's value, was December's issue. Listed in the index, the film gets relegated to the 'Shorter Notices' section where a single damning paragraph (with no writer's credit) awaits your attention…

"…It proceeds in triangular** jerks from scene to scene, linked tenuously and loudly by continuous snatches of music to keep the action going. The potentially excellent cast and the promising comedienne talent of Lynn Redgrave can do little in the face of such opposition from both script and direction."

**What? No, me neither.

Nevertheless, I beg, on my humble knees, to differ.

Presented in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio, Georgy Girl looks solid even if its grading is not as strident with the contrast as other black and white restorations. It's also a tiny percentage softer and grainier but this again never detracts from the drama on offer. There are a few night sequences where the shadow detail is still evident, the specifics of which I may have been happy to sacrifice for a more dynamic black and white. I'm a sucker for contrast but again, it hardly mars the film.

The original mono soundtrack is rendered with great fidelity with nothing hard to discern and nothing recorded and mixed inexpertly.

There are new and improved English subtitles for the deaf and hard-of-hearing.

Audio commentary with Diabolique magazine's editor-in-chief Kat Ellinger

This is a terrific commentary with a more rolling political edge, one that does the film proud. Ellinger's early insight that characters are deepened in novels by their revealed inner lives and have a rough ride without that interior voice in movies is a brilliant point as it refers to all filmed books. Meredith (Charlotte Rampling) is the vilest creature despite her heavenly good looks and in the movie, she is vilified rather than understood as she may have been more on a page. It's Cordelia's path through Buffy but stopping short of showing any humanity whatsoever. Apparently, body conscious Lynn (the face of 60's Weightwatchers) wanted to become a comedian to escape her own body. Our so-named civilised society is anything but when it comes to gender expectations. Ellinger also remarks on how subversive and confrontational the film is with the throwaway but devastating line from Meredith to Jos, "Got rid of two of yours already," referring to two abortions, a line that may have slapped the 'X' certificate on the film before a square inch of flesh was revealed. Jos and his new kind of masculinity is mentioned (it was new at the time, a sort of sixties metrosexual). We get a heartfelt appreciation of Dandy Nichols (Elsie Garnett of course from the classic sitcom Til Death Do Us Part). The news that Peter Wyngarde and Alan Bates lived together and may have been lovers was an eye-opener to me. Ellinger mentions that Georgy is far from a victim in the final moments of the film, which I will not spoil and she suggests that she may be manipulating all those concerned to get her own way. An anti-romance romance film just about sums up Ellinger's take at the end of a terrific, lively and informative commentary.

The Guardian Interview with Charlotte Rampling (2001): an archival audio recording of a career-spanning interview conducted by Christopher Cook at London's National Film Theatre (59' 56")

Rampling is erudite, engaging and informative. She's certainly not too talkative, often answering questions with brief answers which allows there to be a few dead patches where the obviously smitten Christopher Cook was expecting a little more detail. Of note from the interview, Rampling talks about learning the art of being still on screen, an art that few actors have perfected. You can then channel your performance through your eyes. She talks about working with a plethora of Europe's finest directors and the best bit of advice from Dirk Bogarde (even if you're exhausted, never show it. You may be asked to do a minute's scene of a shot that will be eternal on film so you always have to be ready to shine). Rampling is not a fan of rehearsals and never done any research. She "…dares to believe it's in me… Hasn't been too bad, has it?" she says of a wonderful career. Cook is outed as a Zardoz fan and Rampling is surprised it's the one film of her career he picks. She represented Woody Allen's 'ideal woman' and found Paul Newman to be an "exquisite human being." She warmed to success indicating that a performance must have made real contact if so many people pitch up and pay for their ticket. Not a garrulous interviewee but a considered one. Swift to laugh and make fun of her image, she is nonetheless very self aware or rather aware of her gifts as an actress and as a corollary comes across as supremely self-confident. But then this could be the result of great acting.

The Tempo of the Time (2018): a new interview with author, playwright and co-screenwriter Peter Nichols (7' 14")

The famed playwright of A Day in the Death of Joe Egg describes how he was brought in to rewrite the original novelist Margaret Forster's first draft. He describes the heady style of filmmaking in the mid to late sixties – fast cutting as typified by commercials and the directors who moved from advertising to features. It was a style in which 'meaning' was a difficult commodity to communicate, fun to watch but the difference between popcorn and a three course meal. Good writers like three course meals... Nichols talks about how Alan Bates and his contemporaries couldn't keep still… "It went on for about ten years, a crazy time!"

A Wonderful Sense of Freedom (2018): editor John Bloom discusses his work on the film (28' 20")

It's always a thrill to hear the editor's point of view, the craftsperson that is crucial to the success of the emotional power of a film. Bloom is of course (or was as the director is alas no longer with us) the film editor of choice of Sir Richard Attenborough and edited his films Magic and Ghandi. Bloom says that the director of Georgy Girl Silvio Narizzano gave him enormous freedom. An older editor chose to take a directing opportunity, a choice that paved the way for 31 year-old Bloom to try his luck. Safe to say that the success of the film didn't do Bloom's career any damage at all. He delineates the almost forced creative marriage that exists between a director and editor and what an extraordinary marriage it can be. Having said that he grew to dislike dissolves or mixes. This is a film editor after my own heart. Bloom takes us through certain scenes and the decisions made on how they were cut. He remembers telling the producer that losing Vanessa Redgrave due to schedules and gaining sister Lynn was a blessing in disguise. I'd never realised (until Kat Ellinger's commentary and this extra) that James Mason was a northerner and could at last, use his original accent in a part. Bloom also underlines Walter Murch's dictum that continuity comes low on the importance of editorial decision-making and that emotion overrules everything. There's a heart-warming Columbia executive story and a nod to the huge technological upheaval that occurred in the late 80s that changed the way we edit forever. On his editing practice, Bloom quotes Lena Horne on her own art and craft… "I just sort of stand there and just sort of do it…" Editing is so hard to get a handle on because you cannot teach instinct. Every movie is a prototype so therefore every editor's job is utterly mysterious and instinctive. You 'feel' what's not right and almost know for certain when something works… God, I love editing.

Georgy's Geography (2018): a new interview with art director Tony Woollard (3' 02")

Just a short catch up chat with Georgy Girl's BAFTA nominated art director. Woollard describes the slightly different craft of designing for a black and white or colour film and points out that his director was great to work with. This is obviously a small extract from a much longer interview presumably to be used as an extra on whatever movie Woollard worked on that's getting a Blu-ray release.

Going for a Song (2018): lyricist Jim Dale and editor John Bloom reveal the origins of Georgy Girl's famous theme song (5' 10")

Editor and lyricist take us through the evolution of the king of the earworms, the main theme to Georgy Girl. It's fascinating to hear that editor John Bloom laid the main theme to Funny Girl as a temp. That main theme, mood-wise could not be further than the happy-go-lucky, whistley folk smash hit that ended up in its place. For Bloom, this must have gone from a T-bone steak to a marshmallow. But he got over his initial reluctance and was beaten into submission by its energy and outstanding popularity.

Original radio spot (00' 31")

A straightforward US 30 second radio ad for the movie… "This year's Darling…" referencing the film that came a year earlier starring Julie Christie.

Original theatrical trailer (2' 32")

This one's a real curio… salacious, saucy (as we Brits say) and with more than a tad of misrepresentation. Focussing on Redgrave, we fly through the film as if she was picking up and discarding partners over the trailer's running time. Charlotte Rampling gets pasted as a bad girl the moment we clap eyes on her and Alan Bates reveals his playful side stripping as he pursues Georgy through the streets and underpasses of London. I have no clue what the average punter thinks they'd be getting but the music edits in the last ten seconds are rather alarming including a lyrical spoiler of a sort.

Image gallery: promotional photography and publicity material

Here we find 17 black and white production stills and 2 (shown on one screen) publicity shots of Alan Bates. Then on one screen are two posters, an Italian version and a US 'quote' poster featuring pertinent lines from all sorts of glowing reviews. Finally we get the US release poster with the image of the carefree girl (I've not been able to find a photographic model of the artwork and I submit that this is not a faithful rendition of Lynn Redgrave in the part). There's a Frances Ha poster feel to the image, which I like but while Greta Gerwig just happened to be photographed in that striking pose, right arm high, left hand in skirt pocket, hair wild and right leg straining against a pencil skirt with both feet off the ground, the coloured artwork on Georgy Girl has the right mood but is it supposed to be Lynn Redgrave?

Limited edition exclusive 40-page booklet with a new essay by Leanne Weston, Howard Maxford on the film's making, an overview of contemporary critical responses, and film credits

It is with a huge smile that I find our once ace Cineoutsider reviewer Leanne Weston now contributing to the booklets of films she would have loved to have reviewed while still with Outsider. And her essay – Good Girl. Bad Luck: Gender, Morality and Performance in Georgy Girl – is a fine one. Leanne gives the context in which the film was made and puts forward the idea that Georgy and Meredith represent two extreme examples of womanhood at the time, the 'it' girl with all the social choices available to her and her dowdy flatmate destined to pick up the leftover crumbs. Leanne says that "Thematically and tonally speaking, it perhaps hasn't aged well." But I think it's been directed so artfully that those elements didn't bother me at all. Dare I say from a woman's perspective, the lens may be very different from my own. Making Georgy Girl by Howard Maxford is a deft selection of quotations from those involved in the making of the film collected in 1996 by Maxford himself. The idea that at an early screening there were no comments at all and Redgrave and Bates just left for a downcast meal is oddly touching. There are extracts from the critical response at the time and as ever, they make for hugely entertaining reading. A great booklet.

A light-hearted and intelligent examination of significant human issues capturing an era that promised so much, Georgy Girl is a superior slice of sixties entertainment. There are vibrant and engaging performances with Lynn Redgrave's awkward heroine front and centre in a film that manages to air some contentious concerns that still divide people today. But it's all done so skilfully that you never get any impression that 'issues' are being raised. It's certainly one of the best of the sixties' crop. Warmly recommended.

|