|

Paris in the 1950s. Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud) is a young boy living with his mother (Claire Maurier) and stepfather (Albert Rémy). Antoine is at odds with his parents and also his school teachers and is given to playing truant and petty theft.

Some great film directors start slowly, learning their craft over a period of time before making their first major works. One example, a man whose work I’ve reviewed over the last twelve months at this site, would be Ingmar Bergman. However, some land with a splash, with a debut feature that may not ultimately be their greatest work, but is one that they will be forever known by. In the case of François Truffaut, just twenty-six at the start of production, that first film, The 400 Blows (Les quatres cents coups), didn’t just do that to his career when it was released in 1959. Along with Jean-Luc Godard’s own first feature Breathless (A bout de souffle) from the following year, it brought a burgeoning movement amongst younger French filmmakers, known as the New Wave (Nouvelle vague) to international notice. If you regard this film as one of Truffaut’s best or not (I would, though not his very best) and whatever you might make of the ups and downs of his later career, it’s without a doubt a defining work of French cinema.

The New Wave, like many movements in world cinema, had relatively smaller audiences but they were influential. The mass audience at home largely stuck to more traditional and commercial cinema: it wasn’t until The Last Metro (Le dernier Métro) in 1980 that Truffaut, or any other of the major New Wave directors, had a substantial box office hit in France. In the UK and USA, much of the audience for these films were those who might normally go to see subtitled foreign-language films. Yet many of those were themselves filmmakers and the inspiration and influence of the New Wave crossed over into British and American films. You can see several of its innovations in the films made by Woodfall in the early 1960s, for example.

The New Wave was a reaction against traditional French filmmaking, much dominated by staid literary adaptations, which they derisively called “le cinéma du papa”. The key New Wave films are marked by stylistic experiment and iconoclasm, in particular making use of lightweight cameras and faster film stock enabling shooting in the streets. As well as making the reputations of its key directors, the New Wave also helped to establish the careers of like-minded cinematographers such as Raoul Coutard and Henri Decaë.

However, the New Wave was not an especially cohesive group. Some filmmaker contemporaries, such as Louis Malle and Claude Sautet, made use of its innovations, although they were not formally associated with the movement. The New Wave itself was divided into two groups, named after the banks of the River Seine. Those on the “Left Bank” were generally older and had literary backgrounds and a liking for narrative experimentation. Their politics were often in the direction of the bank they were named after. These included Alain Resnais, Chris Marker and Agnès Varda. Also associated with this group were novelists such as Alain Robbe-Grillet and Marguerite Duras, both associated with the “nouveau roman” form, who wrote screenplays and later directed films themselves. The “Right Bank” group had begun their careers as critics, often finding a home in the pages of Cahiers du cinéma. Their key figures included Truffaut and Godard, as well as Claude Chabrol, Jacques Rivette and Eric Rohmer.

François Truffaut, born 1932, was the youngest of these five men, and sadly was to be the shortest-lived. (As I write this, the only major New Wave director still with us is Godard at age ninety-one.) The 400 Blows draws on Truffaut’s childhood, though updated to a contemporary setting rather than the wartime France when Truffaut actually was Antoine’s age. He later played the autobiographical aspect down, after objections by his parents to the content of the film. From an early age, the cinema was an escape for him, sparking a lifelong cinephilia. In 1948 he started a film club and met the critic André Bazin, who became his mentor. After Truffaut had spent time in the French Army, Bazin used his contacts to get him a job at Cahiers du cinéma and for most of the Fifties Truffaut was a critic and later an editor at that magazine. He soon began to make his own films. His first was a short, Une visite in 1955. This was never publicly shown and is now believed lost. His second short was Les mistons (The Mischief-Makers) in 1957, included on this disc as an extra (see below). Then, in 1958 he began work on his first feature, The 400 Blows. Bazin died in 1958 at the age of forty from leukaemia, one day after the start of shooting; Truffaut dedicated the film to him.

Truffaut wrote the script with Marcel Moussy. The title is a French expression, “faire les quatres cents coups”, meaning “to raise hell”, which led the film briefly to be entitled Wild Oats in English before it becoming known under the present title which literally if unidiomatically translates the French. Truffaut by then had met and befriended Jean Renoir, whose films were often seen as predecessors of and influences on the New Wave. Truffaut named his protagonist after Renoir’s assistant Ginette Doinel. Truffaut auditioned several hundred young boys for the role of Antoine, before casting fourteen-year-old Jean-Pierre Léaud, the son of a screenwriter and an actress.

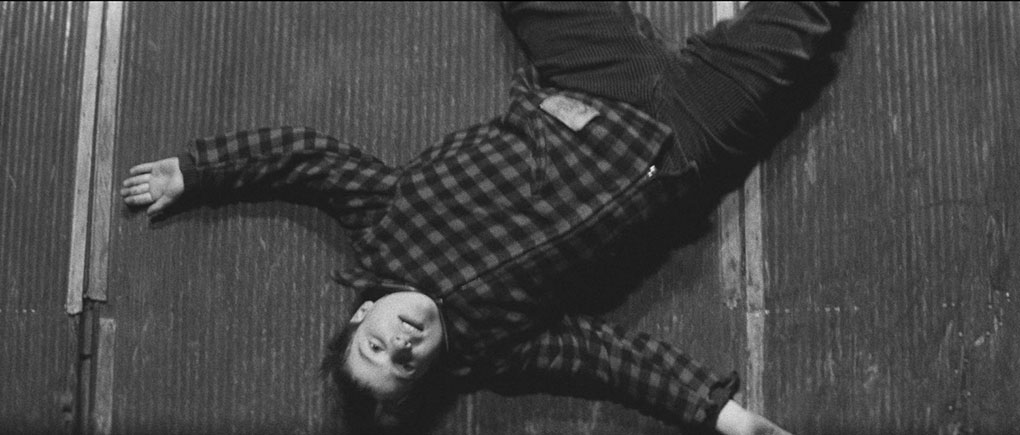

The result is one of the great child performances in cinema, and the start of one of the great director-actor partnerships. Truffaut would return to Antoine four more times, played throughout by Léaud: the short Antoine et Colette (part of the portmanteau feature Love at Twenty, 1962), Stolen Kisses (Baisers volés, 1968), Bed and Board (Domicile conjugal, 1970) and Love on the Run (L’amour en fuite, 1979). Léaud has had a distinguished career away from Doinel and Truffaut, but his debut performance is indelible, the final freeze-frame close-up the perfect closure to it, leaving Antoine on the brink of an uncertain future, but ending on a note of hope.

Several of Truffaut's New Wave colleagues and friends make brief appearances in The 400 Blows: you can briefly glimpse Jean-Claude Brialy and Jeanne Moreau, Jacques Demy, Philippe de Broca (the film's assistant director, later to become a director in his own right) and Truffaut himself. You can also hear the voices of Godard and Jean-Paul Belmondo. It’s often the case that a first-time director has the services of an experienced cinematographer and this was no exception. Henri Decaë was seventeen years older than Truffaut but had entered the film industry via an unconventional route. He had been a photojournalist in World War Two and he had begun his career making documentary shorts, making his feature debut with Le silence de la mer (1949), directed by Jean-Pierre Melville, another predecessor of the Wave who was influential on it. He had worked regularly for Melville and had shot early films by Malle and Chabrol. Because of his experience, he was the highest-paid member of the crew. The 400 Blows was the only film he made with Truffaut, but their collaboration here helped establish a look for the New Wave.

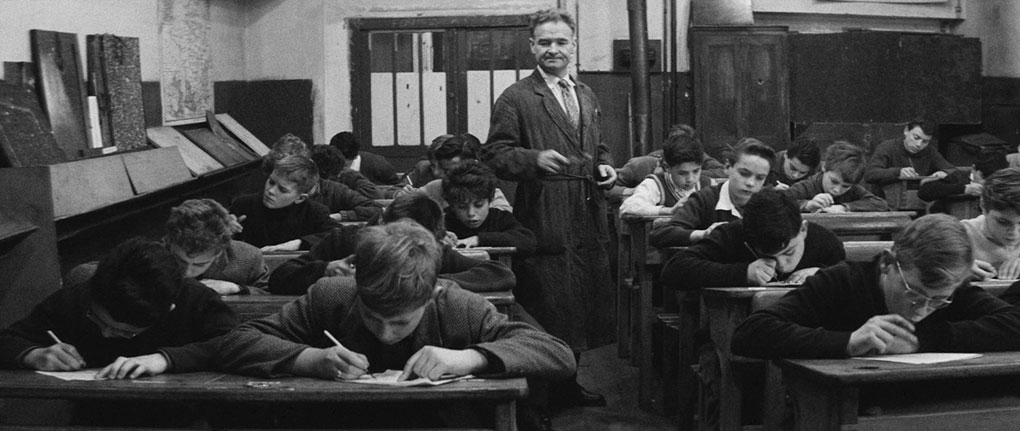

Given how influential this film, and the New Wave, has been, it's hard to recapture the freshness and impact it had at the time. A cinephile to his core, Truffaut was very much alive to the medium’s possibilities. The camerawork is fluid from the opening scene as it moves around a classroom in between the desks. Later in the film, Truffaut and Decaë keeps pace with Antoine running by shooting from a car, a more practical alternative to what would have needed about a mile of dolly tracks. Other than that iconic final freeze-frame, Truffaut's use of cinematic devices, is more restrained, and arguably less self-conscious than it is in the features which immediately followed, Shoot the Pianist (Tirez sur le pianiste, 1960) and Jules et Jim (1962). Given how close to home the subject matter of this film was, The 400 Blows is remarkable for its objectivity and lack of sentimentality. Truffaut certainly didn't always avoid the latter in his later films involving children.

At Cannes in 1959, The 400 Blows won Truffaut the prize for Best Director at Cannes in 1959. It was Oscar-nominated for Best Original Screenplay the following year, along with Hitchcock’s North by Northwest and Bergman's Wild Strawberries. The winner was Pillow Talk, but I doubt posterity agrees. The BAFTAs nominated it for Best Film from Any Source and Léaud as Most Promising Newcomer to Leading Film Roles, but the winners were The Apartment and Albert Finney respectively.

The 400 Blows is one of four Truffaut films to be released by the BFI on Blu-ray, simultaneously with Jules et Jim, with La peau douce and The Last Metro to follow. The disc is encoded for Region B only. There have been previous DVD and Blu-ray releases in the UK and France, and some of the extras on this new edition have been carried over. The film itself carried an A certificate on its original release and is now a PG, and the same applies to the short Les mistons. The remaining extras are documentaries exempted from classification, though the transfer of Metropolitan Railway of Paris begins with the short’s original U certificate.

The 400 Blows was shot in black and white 35mm with anamorphic lenses (Dyaliscope) and the Blu-ray transfer is in the correct ratio of 2.35:1. The transfer is derived from a 4K restoration from the original camera negative. Decaë’s cinematography, making much use of fast stocks and natural light is often quite grainy, particularly in scenes which involved process work (dissolves between scenes, the final freeze-frame). The film is dominated by what was clearly overcast winter weather: it was shot from November 1958 and January 1959, with Christmas decorations in shops and at one point Antoine breaking the ice in a fountain to wash his face. The effect of all of this is that the film is greyscale with hardly any true blacks or whites, but that’s the way it’s always looked.

The soundtrack is the original mono, rendered as LPCM 1.0. The film was almost entirely post-synchronised so audio synch does wonder here and there. The only scene which was shot live was Antoine’s interview by a psychologist at the reform school late in the film, a scene improvised by Léaud. English subtitles, for both the feature, the commentary and the short Les mistons, are optional, so you can play the feature audio with the commentary subtitles or vice versa, or with no subtitles at all if your French is up to it.

Commentary by Robert Lachenay

This was recorded in 2002 and has been carried forward from previous disc editions of The 400 Blows. It’s billed as a solo commentary but it’s actually a two-hander, as Lachenay is interviewed by critic Serge Toubiana. Lachenay, childhood friend of Truffaut’s and assistant unit manager (and uncredited assistant director) on this film and production manager on Les mistons, was the inspiration for Antoine’s schoolfriend René Bigey (played by Patrick Auffay). This track is valuable as it’s an eyewitness account of Truffaut’s life and the making of this film, captured while Lachenay was still alive to put it on record. (He died in 2005.) Lachenay speaks in some detail and is always interesting to listen to. This commentary is in French with optional English subtitles.

Audition footage (6:42)

Also brought forward from previous editions are these screen tests for Léaud solo, Léaud with Auffay, and Richard Kanayan. The latter plays one of Antoine's fellow schoolchildren and also acts in Shoot the Pianist. He ends this item with a rendition of “When the Saints Go Marching In” in heavily-accented English.

Les mistons (The Mischief-Makers) (18:13)

Les mistons is based on a novella, Virginales, by Maurice Pons. Truffaut’s second short was shot in 35mm and Academy Ratio (1.37:1) without direct sound: it has narration by Michel François and a music score by Maurice Le Roux. The story takes place over one summer as an affair between a young woman (Bernadette Lafont) and a young man (Gérard Blain, Lafont’s then husband) is spied upon by a gang of younger boys (the “mischief makers” of the title). In particular, they are infatuated by the woman, trying to catch glimpses of her knickers under her short skirt as she plays tennis with her boyfriend, and no doubt masturbating furiously if the censorship of the time had allowed that to be hinted at. However, there is a tragic ending, underlined by a bittersweet few-years-later epilogue.

Despite the obvious tiny budget, Truffaut’s confidence as a filmmaker is obvious this early on. His affinity with the children (all boys, no girls) is clear and he films them almost documentary-style. He’s if anything more interested in them than in the love affair which is the film’s plot motor. However, he had the services of a star in the making: Bernadette Lafont, who was at the start of a distinguished career, working with many of the major New Wave directors, with Claude Chabrol several times but also with Jacques Rivette, Louis Malle and later Jean Eustache, Nelly Kaplan and Claude Miller. She worked with Truffaut only once more, on Une belle fille comme moi (various English titles, but most recently released on a British disc as A Gorgeous Girl Like Me, 1972), which is a misfire for both her and Truffaut. Les mistons had an effect on her marriage, as Blain was uncomfortable with the attention she was receivng. They were divorced two years later.

Truffaut, Bazin, Renoir: A Love Story (19:41)

This item is new to this disc and is a recording from a Truffaut study day at the BFI Southbank on 29 January 2022. As Truffaut’s films and Renoir’s before him often involve love triangles, Dr Catherine Wheatley delineates a real-life platonic triangle between three men: between Truffaut and his mentor André Bazin and via Bazin Jean Renoir, whose films and aesthetic had been championed by the critic. Wheatley also asks us to compare and contrast two sequences – the famous 360° pan (or not – opinion varies) in Renoir’s Le crime de Monsieur Lange (1936) and the final sequence of The 400 Blows. Unfortunately, the BFI have removed the former clip for licensing reasons, which makes the comparison difficult if you’re not familiar with the film.

Images of Paris

It wouldn’t be a BFI disc if you didn’t have short items like these, from the archive, not specific to the main feature but tangential to it. In this case, three looks at Paris, with a Play All option.

Panorama Around the Eiffel Tower (1:14)

Shot in 1900, this film is made up of four panning shots forming a circle, which take in the feet of the Tower itself, as the emphasis is more on the sights of that year’s World Fair. This was a British production: the Warwick Trading Company specialised in actualities shot around the world, a draw to audiences for whom international travel was out of reach.

Lunch on the Eiffel Tower (1:06)

From a Topical Budget newsreel from 1914, this not only shows us a sight out of reach for most, it shows us visiting dignitaries sitting down to a dinner out of most people’s price range as well. This also takes the opportunity to let the camera move, as it takes a lift journey down the side of the Tower.

Metropolitan Railway of Paris (5:34)

A driver’s eye view of the Paris Métro, whose first line opened during the 1900 World’s Fair, while an unknown cameraman was shooting around the Eiffel Tower. By this time, 1913, the network was eighty-five miles long. Intertitles convey the necessary information, with plenty of shots of a big bustling city a year before War broke out. A couple of shots look very similar to the stock footage of Paris that Truffaut includes in Jules et Jim and may indeed be the same footage.

Original trailer (3:57)

While The 400 Blows was an instant classic from the moment it premiered in Cannes, it’s clear that its French distributors weren’t sure how to sell it to a more general audience when it opened commercially two months later. Hence this lengthy trailer, which is heavy on quotes from critics and a few established filmmaking names (Henri-Georges Clouzot, Jean Cocteau), clearly positioning this film as a work of art, which it is. It’s not quite “miss this film at peril of your soul” but it’s on the way there.

2022 reissue trailer (1:35)

Made for the BFI’s cinema reissue which preceded this disc. More than sixty years later, the likely audience for this film is known, and the BFI’s trailer is much shorter, though it does still contain some critics’ quotes, which are in yellow over the extracts from the black and white film.

Image gallery (1:08)

A self-navigating gallery of production stills, all black and white, and an original French poster, which is in colour.

Booklet

The BFI’s booklet, available in the first pressing only, runs to twenty-four pages. The main essay is “‘The Greatest Film Ever Made About Childhood’” by Ellen Cheshire. She gives an overview of Truffaut’s life up to the point when the film was made, in particularly his meeting with and work for André Bazin, mentor and almost surrogate father. As well as the influence of Renoir, Cheshire picks up on that of Rossellini as well, in particular Germany Year Zero, a favourite of Truffaut’s in particular due to its centring on a child. Cheshire deals with the film itself and its aftermath, with maybe a nod by Truffaut in Bed and Board that maybe he had been too harsh on his real-life parents. This is followed by a six-page biography of Truffaut by Kieron McCormick, film credits, and notes on and credits for the extras.

You can argue if The 400 Blows is Truffaut's best or not – there are other candidates – but it remains one of the cinema's most auspicious debut films and is well served by this BFI Blu-ray.

|