|

The expansive opening shot of the intriguingly titled 1956 film Edge of Eternity, which plays under the titles and beyond, does play a little like a statement of intent by its director, Don Siegel. You all know who Don Siegel is, right? Good, that saves me listing the many fine films that he has helmed. The shot in question begins as a slow pan over the geographical magnificence of Arizona’s Grand Canyon – a location that will be both narratively significant and majestically showcased in the course of the following 80 minutes of screen time – that comes to rest on a distantly located dirt road leading down from an unidentified building on the canyon’s edge. Walking down that road is a figure so small on the expansive CinemaScope screen that even the sharpest eyeball would be pushed to discern even what he is wearing (and we have to wait for the next shot to confirm it that he is indeed a man), and when he realises that a car is heading down the road behind him, he darts for cover between some roadside rocks. Despite viewing events from half a kilometre away, we have been clearly informed that this man is either being pursued by the driver of the car or is keen to avoid being found by that person in this location. It’s a sure sign that we are in the hands of a director with a strong grasp of the visually communicative possibilities of his craft. When the camera moves in closer, the white-haired and grey-suited man driving the car driver stops his vehicle and exits, then stands on the cliff edge peering searchingly into the canyon. The younger man in hiding then sneaks over to the vehicle, releases the handbrake, and pushes it silently towards its owner. At the very last second, the startled older man finally hears the noise that the wheels must have been making on the gravel all along and jumps aside, leaving the car to plummet into the canyon below. I’m relieved to say that it doesn’t explode.

As the two men then grapple on the clifftop, expectations are confounded when it’s the younger assailant who falls to his death, leaving the now injured older man to stumble down the road in search of assistance. We learn that he has found it – in a scene that also begins in the widest of shots – when the elderly Eli Jones (Tom Fadden) stops his steaming old jalopy and flags down cheerful police patrolman Les Martin (Cornel Wilde), whom he tries to convince that a man has shown up at his isolated cabin on the canyon’s edge. Having just watched the above-detailed scene, the audience knows immediately to whom old Eli is referring, but our Les is having none of it, having apparently heard this story a few too many times from delusional old Eli. What’s interesting about this exchange is that functions as our introduction to the film’s lead character, and yet our first reaction to him is not engagement or empathy but frustration at his refusal to treat what we know is important information seriously, and instead simply laugh off Eli’s claims. As a result, we’re initially invited to regard the hero of this tale as something of a doofus. The problem is compounded when mine owner’s daughter Janice Kendon (Victoria Shaw) goes haring past them in a bright yellow convertible, and Martin dismisses the still protesting Eli to give chase. Janice is clearly having a whale of a time driving down winding mountain roads at an irresponsible speed, and when officer Martin finally catches up with her, her attempt to charm her way out of a ticket only meets with partial success. Despite this, there can be few watching who do not twig that this is designed as a meet-cute moment for the hero and princess of this particular story.

The unforced folly of Martin’s decision to dismiss Eli’s claims and chase after Janice instead, meanwhile, is made clear when Eli arrives home to find his house trashed and his grey-suited visitor hanging by his neck from the bedroom ceiling with his hands tied securely behind his back. Despite being morally supported by his easy-going boss, Sheriff Edwards (Edgar Buchanan), Martin is gutted that he didn’t listen to Eli and immediately begins an investigation into this as-yet unidentified man’s death. But two murders later, with little progress made, Martin has his competence questioned by a county attorney (Wendell Holmes) who is plotting to replace Edwards with his own man in the upcoming election, and is forced to wrestle with an error of judgement in his past that resulted in him leaving his former job as a Denver City homicide detective.

Edge of Eternity is an intriguing mix of genres and influences, albeit one that for me doesn’t always quite click, but when it does, it makes for involving and at one point nail-bitingly tense viewing. The film’s noir credentials are evident in the development of the plot and the character of patrol officer Les Martin, a former city homicide detective whose fall from grace following a critical mistake triggered by personal tragedy ultimately led to him relocating from Denver to Arizona, where he was offered a position by the non-judgemental Edwards. There’s also a distinct noirish edge to the murders themselves and particularly to Siegel’s handling of them, from the symbolic through-the-banister-bars framing of the hanged man and Eli’s shocked reaction to a third murder filmed from the viewpoint of the unseen killer, as he is invited in and even handed the murder weapon by his tragically unaware victim. There’s even a whiff of the flawed western heroes of Anthony Mann and Budd Boetticher in Martin’s character, a genre influence that the contemporary Arizona setting only helps to bolster, with its dusty canyon roadways and lawmen who have long since traded in their horses for cars, but who still wear gun belts, tin stars and Stetson hats.

Where for me, at least on the all-important first viewing, the noir influence falters just a tad – and where I find myself disagreeing just a little with Jason Ney on his excellent commentary track – is in the character of Janice Kendon, and if you’re new to the film and want to go in completely fresh, you might want to skip the rest of this paragraph and the one that follows to avoid what for many will count as spoilers. In Ney’s view, Janice is initially a possible suspect for the killings, at least until her actions strongly indicate otherwise, and maybe it’s just me but I never once even suspected she was involved in the murders in any way. From her very first appearance, tearing down winding roads at a reckless speed with a self-satisfied smile on her face, for me she projects the image of a woman whose sense of entitlement and privilege have resulted in her not taking responsibility of her actions and believes that the rules of society simply do not apply to her. I’m sure you can all draw your own modern day parallels to that one. Full marks to Siegel for communicating this in such a short space of screen time if that was his intention, but it’s safe to say that as a result, my first impression of Janice was not exactly a favourable one. Neither she nor Cornel Wilde exactly set the screen alight in the early scenes, with Wilde not projecting the hoped-for easy charisma as Martin,* and Australian actress Victoria Shaw initially coming across as a cheerfully cosmetic inclusion whose prime purpose was to provide a love interest for the widowed officer.** Many will disagree, but I have to admit to finding their light-hearted scenes together a lot less engaging than the murder mystery that occupies the rest of Martin’s time.

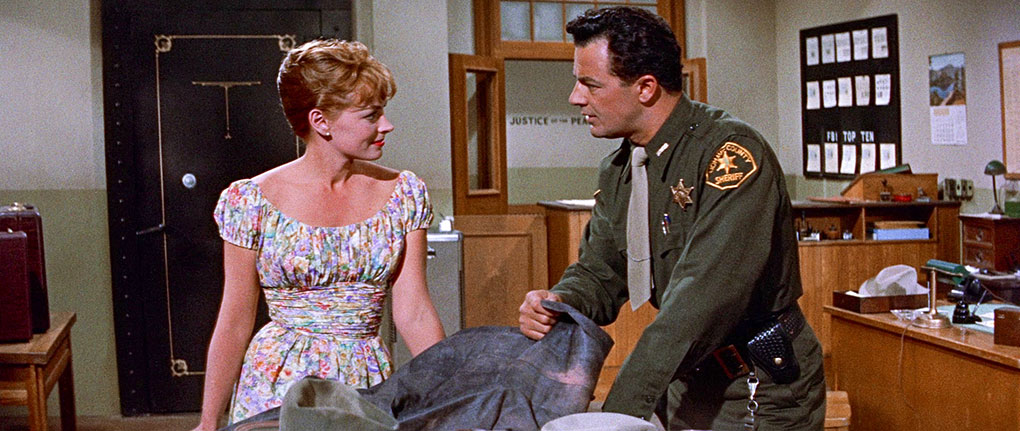

My mild irritation at these romantic interruptions peaks after Martin has been grilled in a coroner’s inquest and is warned of possible resignation pressures by the pleasingly supportive Sheriff Edwards, and he is prodded by the desk officer to respond to an endless stream of unimportant phone messages from Janice, who then swans into the station and smilingly demands that he buy her a hamburger. He’s busy, for heaven’s sake! There are three murders to solve! Then, as the two prepare to nip out for an investigation-pausing lunch, a casual comment from Janice, one she is only able to make because her upmarket background and lifestyle, unexpectedly proves to be the clue for which Martin has been desperately searching. In this moment, the elements of Janice’s character that had previously rankled me suddenly made narrative sense, and from that point forward I was fully on board with everything she and Martin did. I also found myself rethinking my initial judgement of a character I’d initially – and unfairly – believed was little more than a fluffy distraction from what was otherwise an engrossing drama, and better able appreciate just what Shaw and Wilde were bringing to their roles.

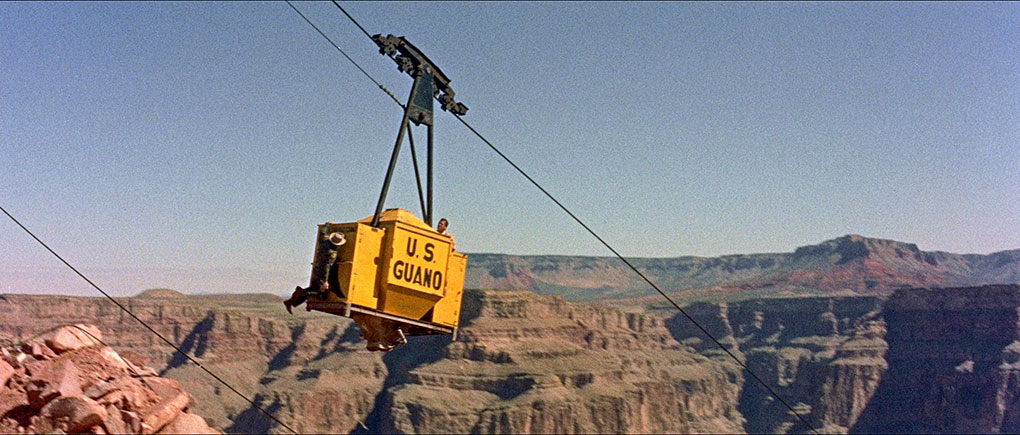

That all said, I still think the supporting characters are more instantly engaging than the leads, thanks in no small part due to some fine performances from a well-chosen cast. Take Janice’s heavy-drinking and father-hating brother Bob, a character that would normally be presented in a strongly negative and even violent light, but as played by Rian Garrick he comes across instead as an easy-going, passive and rather likeable lush. Later revelations cast his alcoholism in a speculative light, leaving me wondering whether he was drinking because of something that he’d done, or was easy to manipulate by selfish others because he was a little too fond of his booze. Mickey Shaughnessy is a lively presence as perennially upbeat bartender Scotty, and Tom Fadden injects just the right amount of character actor eccentricity as old loner Eli. But my favourite performance in the film comes from favourite character actor Jack Elam as aerial bucket tramway operator Bill Ward, a winningly naturalistic portrayal that feels like the flipside of his more colourful later roles, and shows what a fine actor he really was. Oh, and if you smile at the idea of a firm named U.S. Guano (I certainly did), know that this was a very real company at the time of filming, and the featured aerial tramway bearing its name was used to transport mined bat faeces from a huge cave on the far side of the canyon to be sold as organic fertiliser.

The majestic aerial CinemaScope shots of the Grand Canyon, courtesy of second unit cameraman Wilfred Kline, probably worked wonders for the Arizona tourist board and must have looked astonishing (if occasionally stomach-churning) projected on a large cinema screen, but are never superfluous to the scenes in which they appear. Siegel also does a solid job in keeping the investigation on the boil through the pauses for Martin and Janice to get smiley at each other but really comes into his own when the action hots up, warming up with a couple of car chases and hitting a nerve-wracking climactic peak with a precarious battle aboard the aerial bucket tramway. The process work on the close-ups in this scene may not completely convince in these days of digital compositing, but they’re better than many of their ilk and the stunt work on the wide shots is all for real, and at times had me genuinely holding my breath at the risks the stunt performers seemed to be taking. I was comforted to learn that invisible safety measures were in place, but still salute the bravery of the performer who leaps onto the bucket as it departs, then appears to slip and is left dangling by a single hand, and at a point when he had apparently cleared the safety net put in place to catch him if he fell. It makes for a suitably tense and spectacular climax for a film that may have its narrative logic hiccups and untied loose ends but remains an enjoyable and well-crafted blend of crime drama, whodunnit and noir thriller with western overtones, one whose solid lead performances are ultimately outshone by a fine supporting cast and some standout scenes, and the natural splendour of the location in which it is set.

Sourced from a Sony HD remaster of the film, the 2.35:1 transfer on Indicator’s Blu-ray is impressive, boasting strongly defined detail whose crispness is highlighted when Martin first talks to Scotty in his bar, where the difference in sharpness between the two characters is illustrative of how unusually shallow the depth of field was here. There’s an earthy look to the colour in the Grand Canyon scenes that is reflective of the rock face and dirt road surroundings, but there’s an otherwise pleasingly naturalistic look to the palette, and the brighter colours pop without feeling oversaturated. The contrast grading is generally spot-on, with solid black levels, cleanly rendered highlights, and a generous range of tones between. The image is free of dirt and damage and is stable in frame, and a fine film grain is visible throughout.

The original mono soundtrack, which has also been remastered, is presented here in Linear PCM 1.0 and has the expected restrictions in tonal range, but is otherwise clear and free of distortion or obvious signs of damage or wear.

Optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired have been included.

Audio Commentary with Jason A Ney

Professor and film scholar Jason A Ney is clearly an enthusiastic fan of the film and an absolute fountain of knowledge on its making and background, and has plenty to say about it, its makers, and specific shots and scenes. It’s a compelling listen, and while we may have our minor differences of opinion when it comes to the lead characters, I still found this a fascinating and hugely educational listen. Ney identifies locations used and even the models of vehicles being driven and flown, and talks about the lead actors and their characters, Siegel’s role in the development of screen violence, the film’s noir elements, the range of pre-release alternative titles, and quotes director Siegel and producer Kendrick Sweet on the origins, development and production of the film. We get detailed histories of the U.S. Guano company, the famously pseudonymous credit, “An Alan Smithee film,” and Charlie Hing Lum, the Chinese immigrant who started the Jade Café in which one of the scenes of the film is set. Ney is not above highlighting the elements that don’t quite click, including the back-projected studio driving shots in which Cornel Wilde is seen constantly rotating the streeting wheel back and forth as if weaving in and out of a line of bollards, but concludes by describing the film as “a tightly paced, professionally executed mix of genres, with solid directing and good acting.” No argument here.

Into the Canyon: José Arroyo on Don Siegel (16:49)

Writer and academic José Arroyo clearly knows his Siegel, and here delivers an informative and always interesting overview of the director’s early career, from his early days as head of montage at Warners through several of his key early films, including The Big Steal (1949), Riot in Cell Block 11 (1954), Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) and The Lineup (1958). He reveals that the first retrospective of Siegel’s films was held at London’s National Film Theatre in 1968 – which predated most of the films for which he is most famous today – proposes that the most characteristic element of his films is the sense of characters at odds with or apart from a corrupt and unjust society, and suggests that his early collaborations with Clint Eastwood became a template for action movies in the 1980s.

Closer to the Edge: José Arroyo on ‘Edge of Eternity’ (30:01)

Here, Arroyo focusses exclusively on Edge of Eternity, examining and deconstructing specific scenes in more detail than regular commentaries would normally allow by letting some sequences play uninterrupted and then pausing the film to elaborate on points that would otherwise have to be truncated by the time available. Several of his observations directly echoed my own (prompting the usual groan from a writer whose review was already complete by this point and who winces at even a suggestion of plagiarism), but there are still plenty of points made here that hadn’t occurred to me, and Arroyo’s theories about the meaning behind the film’s use of the colours yellow and red made me want to immediately rewatch it with this in mind.

An Australian Cinderella: Stephen Morgan on Victoria Shaw (16:40)

Academic Stephen Morgan examines the career of Australian actor Victoria Shaw, relating the most plausible of several stories about how she became a contract player at Columbia, and providing details of her marriage to fellow actor (and later producer) Roger Smith, and how repeatedly putting her career on hold to have children may have prevented her from hitting the heights of stardom that she deserved. He praises Shaw’s performance in Edge of Eternity, proposing that the small imperfections in her delivery the second time that Janice and Martin meet were intentional and make her character feel more real.

Image Gallery

34 screens of promotional imagery, including production stills, lobby cards, and a generous selection of posters.

Booklet

Leading the way here is a new essay by prolific film writer Peter Cowie, who praises the film and highlights how Don Siegel’s direction contributes to its success, as well as providing concise overviews of the careers of Siegel and lead players Cornel Wilde and Victoria Shaw. Cowie also reveals that the climactic and seemingly death-defying stunt work on the aerial tramway was performed by professional aerialists, a fact then confirmed in an article written for the December 1959 edition of American Cinematographer by the film’s producer, Kendrick Sweet. Here, Sweet recalls the initial inspiration for the film and the process of getting it into production, including the commissioning of the screenplay, the decision to shoot in CinemaScope, and the selection of the director and cinematographers. He then goes into considerable detail about the technical aspects of the shoot, which should come as no surprise to readers of the journal in question and had me glued to the page. This is followed by an entertaining extract from Don Siegel’s posthumously published autobiography, A Siegel Film, in which he shares a few memories of the production, including the revelation that Kendrick Sweet wanted Jack Elam to play the lead, an idea rejected by the studios because of the actor’s lack of star power. Frankly, that’s a version of the film I’d really like to have seen. Also included are credits for the film, and the booklet is nicely illustrated with production stills and artwork.

A solid mix of genres that it took me a while to get into but that I really warmed to on a second viewing. I still feel that the supporting players tend to outshine the leads, despite solid work from Cornel Wilde and Victoria Shaw, but it’s in the central investigation and the action scenes that the film really shines. Another excellent transfer from Indicator is backed by some very good special features on a typically excellent Blu-ray. Warmly recommended.

** This is, of course, another example of a hugely popular movie trope, one doubtless born of a more censorious time when even extramarital attraction was deemed as unacceptable on screen, where two attractive and popular individuals, both of whom would have no trouble whatsoever finding partners in the real world, are mysteriously single at the same time and are not only mutually attracted but turn out to be just perfect for each other.

|