|

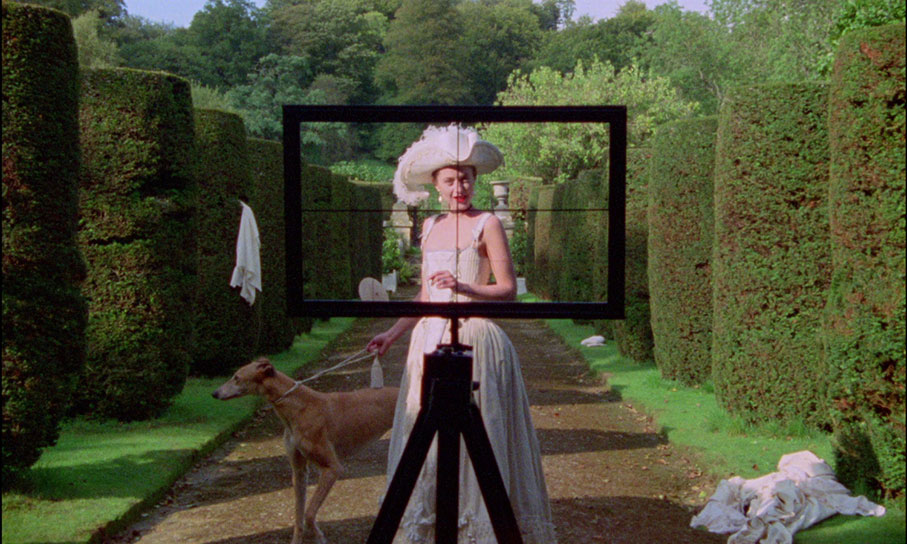

1694. Mrs Herbert's (Janet Suzman) husband is away. She commissions arrogant young artist Mr Neville (Anthony Higgins) to produce twelve drawings of the country house and buildings and estate. Neville agrees with the request that for each completed drawing he has a sexual favour of Mrs Herbert. She agrees, and the drawings commence...but is there more to this than meets the eye?

To many people, the cinema release of The Draughtsman's Contract, in November 1982, drove a stake into the ground of British cinema. Or maybe into its heart, depending on your point of view. It was Peter Greenaway's second feature film, but you could be forgiven for not having caught up with The Falls (1980), a BFI-made non-narrative piece, distributed non-theatrically in 16mm, running three hours. Other than his experimental film work, he made quite a lot of short films as well as documentaries made for the Central Office of Information (COI) where he worked as an editor as well as a director. Before then, his earliest ambition was to be a painter, and it shows. Not the most obvious person to deliver a box office hit...but that's what The Draughtsman's Contract became, certainly in arthouse terms. It came out around the same time as the first productions funded by Channel 4, which launched in November 1982: films intended for cinema release which would then be shown on the television channel. However, there was a backlash, which often happens when what is niche and "arthouse" appears to be mainstream, and questions asked as to why films like this were being made when no one was making anything for a wider audience, with the accompaniment of words like "pretentious" and "elitist". Well, maybe, but The Draughtsman's Contract remains one of Greenaway's most approachable works, standing up very will in this restoration forty years later.

There's a tendency to identify at least two strains of British cinema, with consequent arguments about which might be favoured the most. There's the naturalism and realism, often immersed in socio-political issues, that goes back decades but would include the Woodfall Films of the late 1950s and early 1960s, all the way through to much of the work of Loach and Leigh, Andrea Arnold, Clio Barnard and others. On the other hand, there's a romantic strain of British filmmaking, which includes the work of Roeg, Russell, Jarman, Boorman and Powell and Powell and Pressburger, often responding to the land of this country, its traditions and folklore, often disruptive and certainly not always "respectable".

The Draughtsman's Contract epitomises a third strain: drawing on more experimental models, more formalist, foregrounding structure over characterisation and plot in the usual sense (for example, compare the numerical sequence that structures Drowning by Numbers). Many of those models are European: one of Greenaway's foundational films was Last Year at Marienbad, and through much of the 1980s he had a working relationship with that film's cinematographer Sacha Vierny. Films of this type are often abstruse but one reason why The Draughtsman's Contract was as successful as it was was that Greenaway managed to combine such concerns with a plot – and there is one, with a few surprises which I won't spoil for you. There may also be a bit of Walerian Borowczyk's Blanche in there too – an arthouse hit in London in the mid 1970s, which Greenaway could well have seen at the time – a different story in a different historical setting, but with a striking use of contemporary musical instruments and the almost eerie sound of a countertenor over the opening credits.

Another person who Greenaway developed a strong working relationship was Michael Nyman, at the time a music critic and a composer very much in the minimalist/serialist vein. In fact, he had begun his collaboration with Greenaway four years earlier, on the short films A Walk through H (see below) and Vertical Features Remake, with The Falls in between. His score for The Draughtsman's Contract, drawing on Purcell, sold a good few soundtrack LPs, though not as many as Nyman's later score for Jane Campion's The Piano.

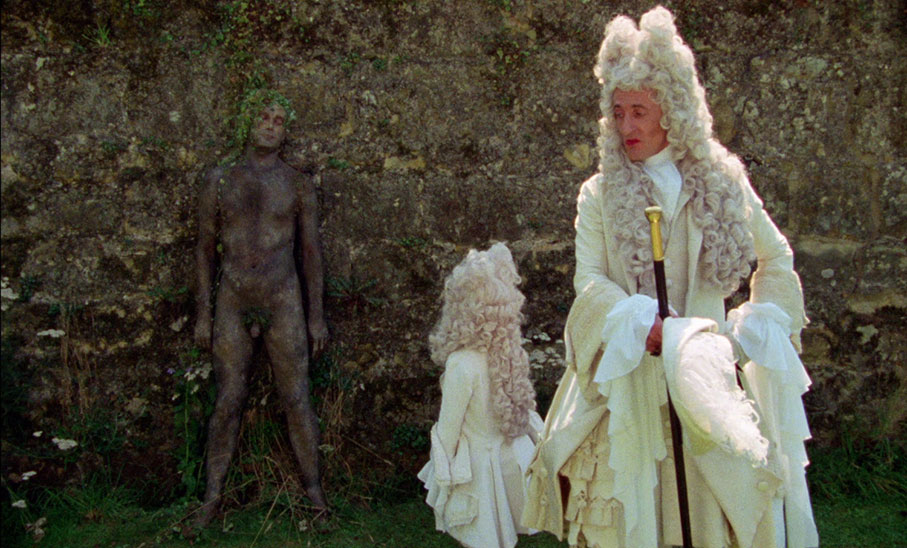

The Draughtsman's Contract was the only collaboration between Greenaway and American-born DP Curtis Clark, shot in Super 16mm, though not that you'd know it. (Greenaway's collaboration with Sacha Vierny began with his next feature, A Zed and Two Noughts.) With hindsight, we can detect flashes of a sometimes scatalogical sense of humour amongst the stylised dialogue, and Greenaway throws in odd touches such as a naked man who turns up, posing as a statue. The ending, and again no spoilers, touches on the grand guignol that Greenaway took to greater lengths in The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover (a major out-of-genre horror film of its time and many people's favourite Greenaway...or many the Greenaway film for those who don't usually like Greenaway films) and The Baby of Mâcon (which went too far for many people to take and possibly damaged his career, commercially at least). For some time, Greenaway's films weren't distributed in his own country (we've yet to see the three-part The Tulse Luper Suitcases on any size screen). Much of his now audience is overseas, as is a lot of his funding, specifically from the Netherlands, where he now lives.

This isn't really an actors' film, but the cast do deliver the dialogue with aplomb. Anne-Louise Lambert splits her cult stardom between this and Picnic at Hanging Rock seven years earlier, and would go on to play Lucrezia Borgia in the BBC's disastrous serial The Borgias.

The Draughtsman's Contract is a two-disc release from the BFI, both Blu-ray discs encoded for Region B only. The film had a AA certificate in 1982, restricting the film to fourteens and over, just before the BBFC revised its age restrictions and replaced the AA with a 15, which this film still has. A Walk Through H, an A certificate in 1979, is now a U, as is H is for House. Zandra Rhodes is a documentary not required to be certified, and it contains nothing untoward.

As it says above, Curtis Clark's cinematography was shot in Super 16mm , though you'd need to look hard, with a practised eye, to tell much difference between this and a 35mm-originated film from this transfer, based on a 4K restoration. The grain is a little more noticeable, but the colours are vivid.

The main feature and several extras are transferred at 1080p with a speed of twenty-four frames per second. However, the following extras are PAL-format SD (576i) and play at 25 fps: the Peter Greenaway introduction, H is for House, Angela Carter's appreciation, the Michael Nyman interview, behind-the-scenes footage, archival interviews, deleted scenes and outtakes and the 1982 trailer.

The soundtrack is the original mono, rendered as LPCM 2.0. It's mixed on the low side, so you do have to turn it up a little, but the dialogue and music, are clear and well-balanced. English subtitles are available for the hard-of-hearing, on the main feature only. The disc also includes an audio-descriptive soundtrack and a German dub.

Commentary by Peter Greenaway

Recorded in 2003, this is wide-ranging commentary in which Greenaway gives us a thorough overview of the film's inception and production. As you might expect, he spends more time on aesthetic principles than on anecdotes about what the cast did on or off set, but with that in mind he's often fascinating. Near the end, he says that – at the time – if cinema had "all the vowels and consonants", (analogue) video was all consonants, a far more visually limited medium. Now, of course, with the rise of digital video, in many ways cinema can go beyond what is possible even with 35mm film.

Introduction by Peter Greenaway (9:55)

Also recorded in 2003, Greenaway talks of his film and how it came about. Being a Greenaway piece, there are frequent illustrations in small thumbnails to the left and right of Greenaway's head, following on from his experiments with such devices in The Pillow Book and Prospero's Books in particular and also the TV series A TV Dante.

Interviews (4:52)

On-set interviews with Janet Suzman, Anthony Higgins and Greenaway. For Suzman, working with Greenaway was the draw, and she remembers having one of the largest scripts she'd ever seen delivered to her home. Greenaway was apprehensive about working with actors for the first time (at least to this extent) but both Suzman and Higgins think it worked. As all the actors earned the same, they thought there was more of a collaborative element than there might have been.

Behind-the-scenes footage (5:29)

Fly-on-the-wall material that shows how much actually goes on in a film set before you get to actually shooting something.

Deleted scenes and outtakes (10:03)

Six of them, with a Play All option: "Chair" (5:30), "Misadventure"(2:26), "Rain" (1:17), "Watercress" (0:25). "Headshot: Mr Herbert" (0:34) and "Headshot: Mr Neville" (0:18). All of these are in a rather rougher state than the fully-restored feature, and it's not hard to see why they were removed.

Original theatrical trailer (1:39)

2022 reissue trailer (1:22)

A sub-menu from the main extras menu, but without a Play All option. The 1982 version, with its then-unknown writer/director and not-unheard-of-but-not-starry cast, opts to use Nyman's music and dialogue from the film over other shots from it to outline the film's premise. Forty years later, much the same trailer (though different shots from the feature) and now we can include critics' quotes and a caption about the 4K restoration.

Image gallery (4:09)

This begins with the draughtsman's drawings, followed by production and publicity stills in colour, and finally the UK poster.

On to Disc Two.

Visions: A Film Comment by Angela Carter (20:39)

Channel 4 was launched on 2 November 1982, and its first film programme was Visions: Cinema, which tended to be pitched rather higher than Film 82 (from which Barry Norman was taking a year off) on the other side. That said, it did take some notice of what was coming out, and in its first edition gave itself over to award-winning novelist and short-fiction writer, and clearly film buff as well, Angela Carter. (I was watching.) She provides a twenty-minute appreciation of a film she describes as "sensuous, glossy, witty, literate, sensuous and coldly sexy". So there you go. The clips from the film are shown in the correct ratio but heavily windowboxed, which was the practice of this programme. Visions: Cinema ran monthly until 1985.

Michael Nyman interview excerpt (6:38)

Not audio-only as some advertising material has it, this is an extract from a National Film Theatre interview from 2002 with David Thompson, in which he discusses The Draughtsman's Contract and how he came to meet and work with Greenaway. He began as a music critic and musicologist, and says he'd hate to do that job again, given that he'd have to write about himself.

The Greenaway Alphabet (60:25)

Made in 2017, when Greenaway was seventy-five, this is a portrait of the man by his wife, Saskia Boddeke, a multimedia artist, as he spends time with their sixteen-year-old daughter Pip. Ideas flow back and forth, father and daughter being equals in this respect. You can see a side of him that in his heyday had him condemned as pretentious, arrogant and elitist but maybe in later life he has mellowed. Given his emphasis on ideas rather than the people in his films, Pip wonders if he is on the autism/Asperger's spectrum. He does mention his often-quoted comment that he would kill himself when he reached eighty, but he is of that age and as I write still with us.

H is for House (8:48)

We now go back for three items from Greenaway's back catalogue. Made in 1974, H is for House...and lots of other things beginning with the same letter, in Colin Cantlie's detached narration. Meanwhile, a young child (the voice of Greenaway's daughter Hannah) calls out words beginning with other letters, from which Cantlie's voiceover takes us off on multiple digressions, accompanied by low-key, often grainy 16mm camerawork. All the camerawork and editing was Greenaway's work and you can hear his voice on the soundtrack.

A Walk Through H: The Reincarnation of an Ornithologist (42:13)

Made two years later, A Walk Through H is on a larger scale, its running time pushing that of a short feature. Again there is a narrator (Colin Cantlie again) and the film asks us to make correspondences between voice and image (Greenaway not behind the camera this time, the cinematographers being John Rosenberg, with rostrum work by Bert Walker). By now, Michael Nyman has arrived in Greenaway's universe. And the attachment to the eighth letter of the alphabet continues, though this time H is a mysterious country our narrator travels through by means of ninety-two maps. Tulse Luper turns up again, as our narrator's facilitator and the supplier of said maps. Or maybe not… "perhaps the country only existed in its maps, in which case the traveller created the territory as he walked through it." The film also overlaps with The Falls, two years later. A Walk Through H had a small cinema release with another long short of about the same length, .

Insight: Zandra Rhodes (14:39)

Made in 1981 for the COI, this documentary may come as a surprise. It's unfair to call it work for hire, but that is what it is – a brief portrait of the fashion designer, made up of interview material and fly-on-the-wall footage. Needless to say, it's the least personal and most conventional of all of the films included here, but Greenaway takes the opportunity to play with colour, and the film is a portrait of an unconventional artist by another unconventional artist.

Booklet

The BFI's booklet, in the first pressing only, runs to thirty-eight pages. It begins with a statement by Greenaway from Summer 2022, recalling both the success of the film in 1982 and the backlash against it. But he has happy memories of making the film without which, you could well argue, he would not have the career he has had.

That backlash is summed up by the title of Simon Barker's essay ' We Could Have a Cinema of painters instead of a cinema of writers!" He describes what is one of his favourite films, seen during its original cinema run at the Screen on the Hill in Islington, London. Barker pays great attention to the film's intentional artificiality. Nyman's music, the intentional symmetrical compositions of the cinematography, the colour-coding of the costumes, all play their part. He also describes how Neville's drawings – twelve of them, but there are only eleven shown on screen – Greenaway got bored, apparently. However, the drawings give the film its structure, subdividing it into sections. Barker points out a few other "frames" throughout the film.

Finally, he talks about Greenaway's wish for a cinema based on the visual rather than the literary (though there's plenty of the latter in his script). Greenaway takes this up in a short piece from 2004, where he says that he was challenged to make a film where characters spoke to each other rather than to camera, and this was the result. Greenaway also points out the significance of the year 1694 to the story: without any spoilers, the Married Women's Property Act was passed, so women could own their own property.

Next up is "A Contemporary Production Report: New Directions in British Filmmaking?" by Robert Brown, which covers both The Draughtsman's Contract and also The Falls. "Gathering Greenaway" by William Fowler goes into more depth about Greenaway's earlier work, tracing their influence on later filmmakers such as Andrew Kötting and Patrick Keiller. Charlie Brigden contributes "The Composer's Contract" on Michael Nyman's score, in particular his use of motifs from Henry Purcell.

Finally there are notes and credits on some of the extras, namely the short films. Unusually for a BFI release, there's nothing on the other extras, at least not in the PDF copy supplied for review.

The Draughtsman's Contract was a significant film in many ways, not least for changing the path of an avowedly experimental filmmaker into one with a larger, more commercial (relatively) audience. Needless to say, the film, and Greenaway have had their detractors since. Restored for its fortieth anniversary, the film looks glorious and is well served on this BFI Blu-ray.

|