|

Although Romanian cinema has become big arthouse business over the last two decades, thanks to the still ongoing Romanian New Wave, it was practically terra incognita in the so-called West throughout the twentieth century, with only occasional festival outings for the work of Ion Popescu-Gopo and Lucian Pintilie. In particular, the extreme censorship imposed by dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu (who ruled Romania between 1965 and his ousting and execution in 1989) made it all but impossible for a local “new wave” to parallel what was happening in France, the UK, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Poland during the late Fifties and Sixties.

Animation was one of the few areas in which Romanian cinema had any international appeal, thanks initially to the widespread popularity of animated shorts by Popescu-Gopo, which date from 1950. He never made an animated feature (although his effects-heavy live-action films are well worth tracking down), but his international success underpinned the creation and ongoing viability of the Bucharest-based Animafilm studio, which was active from 1964-89 before being compulsorily privatised after the collapse of Communism. During that time, it made 1,260 individual productions, the overwhelming majority being short films and TV episodes, but they also produced seven features, of which Delta Space Mission (Misiunea spaţială Delta, 1984) was the second*. At its height, Animafilm was responsible for 40% of the foreign-currency income generated by Romania’s film industry.

So, what does a mid-Eighties Romanian animated sci-fi feature film look like? And, equally pertinently, sound like? In fact, let’s kick off with its most immediate pleasure, Călin Ioachimescu’s synthtastic prog-rock score – the film may notionally be set in the year 3084, but I can only assume that there was some kind of festival going on to mark the 1100th anniversary of the 1980s. The bleepy electronic sound effects will also sound very familiar to devotees of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop in general and pre-1989 Doctor Who in particular. God knows what present-day kids will make of this, but people like me who came of age back then will have had plenty of nostalgia buttons firmly pushed well before the film has properly started.

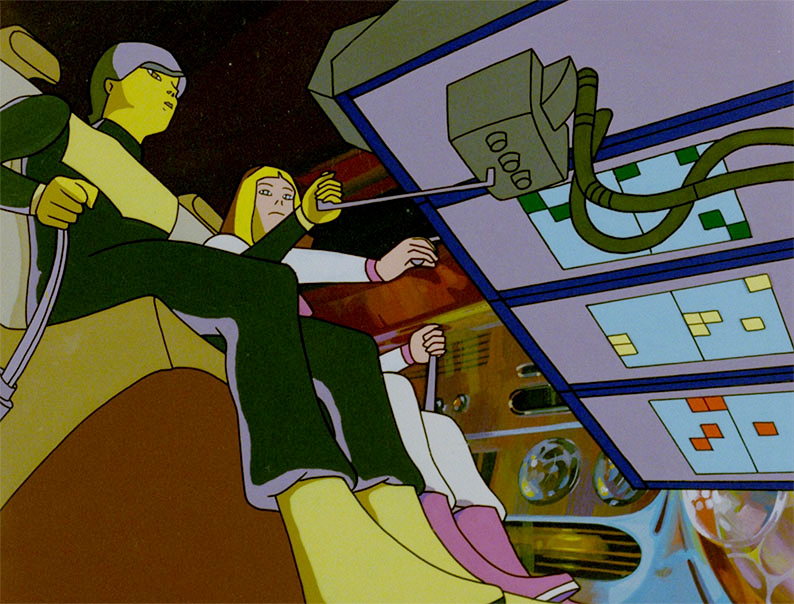

After this promising start, I have to confess that my heart sank during the opening scenes, where a combination of what looked like cost-cuttingly primitive animation (the backgrounds were static paintings, the cel-animated characters so minimally defined that I was largely reliant on the narration to get a sense of who they were) and a near-continuous voiceover spouting all too familiar generic scene-setting sci-fi bollocks made me wonder if I was even going to get through the first few minutes, never mind the whole thing. (“A cosmic vessel is stranded due to an on-board explosion. The ship’s pilot must be saved. Two young astronauts are on a rescue mission. We will follow them, and others, through many unusual events, with the hope that they will become our friends.”)

But, unexpectedly and disarmingly, I found myself very quickly won over. Firstly, although the human characters would never make much of an impression on me (I could only reliably tell them apart because Dan was vaguely Caucasian, Oana female and blonde and Yashiro Dayglo-yellow Japanese), things perked up considerably with the arrival of the pilot of the stranded ship, Alma, self-described “intergalactic reporter from Planet Opp”, complete with “Tin, an alien dog, a mischievous yet loyal friend”.

Despite Alma’s exaggeratedly curvaceous voluptuousness offering a regular reminder that this film’s original target audience was heavily made up of horny teenage boys, she’s also very much her own woman, albeit one whose skin colour is somewhere on the spectrum between blue and green (according to the prevailing lighting) and whose hair is what Peter Strickland’s In Fabric described as “artery red”. Tin is very much the film’s cuteness repository, although he looks and behaves more like a robot amphibian than anything flesh-and-blood canine. He is, however, unquestionably mischievous and loyal, and I strongly suspect that Alma and Tin’s situational if not surface resemblance to Hergé’s immortal Tintin and Snowy wasn’t the least bit accidental.

And Alma needs Tin’s loyalty, because a throwaway comment about how beautiful she finds the Delta space station’s electronic superbrain (which looks like a gigantic diamond with so many coruscating facets that it’s quasi-spherical) causes it to think that Alma has fallen in love with it, and unfortunately it very much feels the same way. A decidedly sinister early touch is that she has a name that’s almost a phonetic dead ringer for “al mea” in Romanian, which translates as “mine”, a possessive attitude that the Delta superbrain will maintain throughout the rest of the film in a fashion that distinctly recalls the premise of Donald Cammell’s Demon Seed (1977) more than anything especially teen-friendly – in the accompanying booklet essay, Stephen Bissette notes that this means that the film has a surprising amount to say to a post-#metoo audience some four decades later.

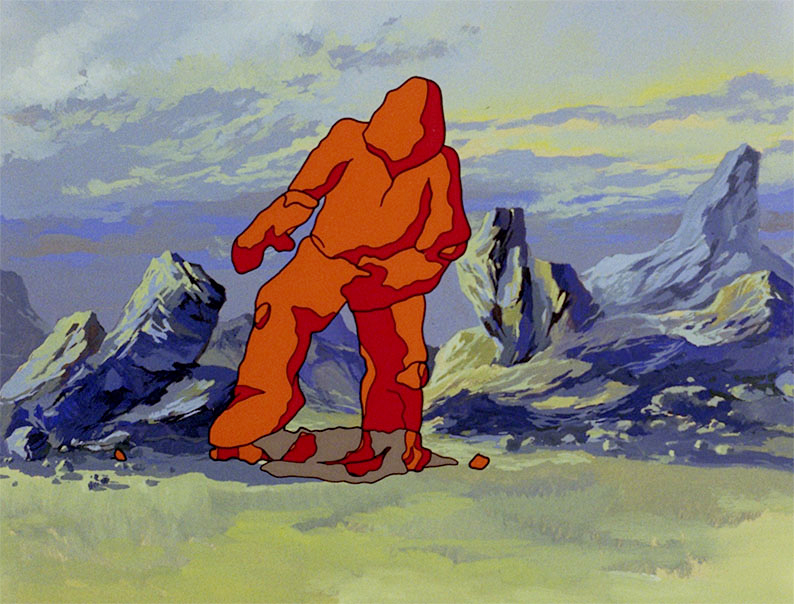

The film’s first sustained action set-piece occurs on Earth, where Alma decides to have a holiday while recovering from her earlier near-death experience. But while Tin is frolicking on a beach without a care in the world, the Delta superbrain tracks Alma down and decides to capture her. Being a mighty electronic superbrain, it doesn’t resort to conventional methods like hiring human kidnappers – instead, it transmits energy beams that successively turn a pile of rocks, an ocean wave and an electricity pylon into gigantic humanoid monstrosities. But after they’re defeated by the collective firepower of Alma’s human friends, she’s free to carry on exploring the cosmos.

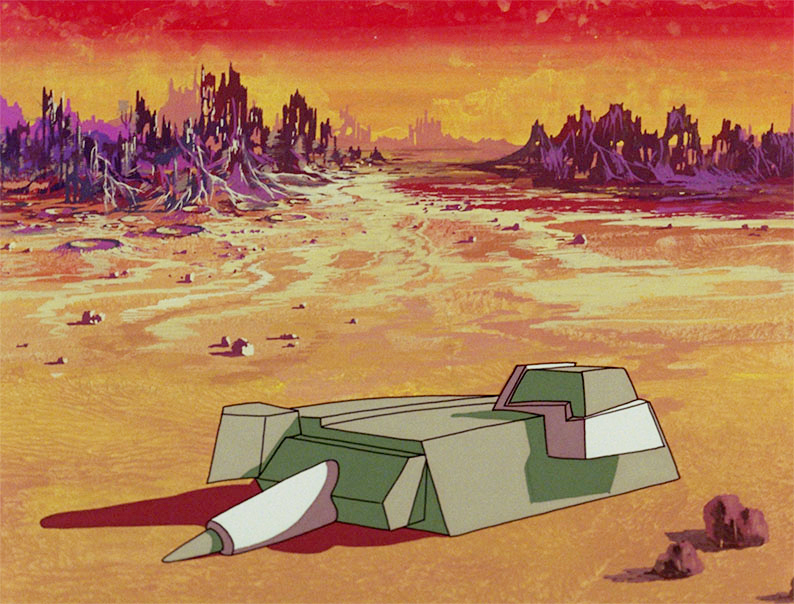

After a very pretty (if logistically baffling) voyage through an asteroid belt, Alma ends up crash-landing on the planet of Acora (the crash, of course, being engineered by the Delta superbrain). Most of the film takes place there, which isn’t remotely a complaint as Acora turns out to be a bizarre wonderland full of the kind of imaginative flora and fauna that wouldn’t look at all out of place in René Laloux’s Fantastic Planet (La planète sauvage, 1973), perhaps the closest direct precursor to this film (and which was also made behind the Iron Curtain, albeit Czechoslovakia in this case). Although there are plenty of chases and battles along the way – at one point the Delta superbrain unleashes an army of robots, many of which look like kitchen white goods turned unexpectedly lethal – it’s the sheer strangeness of the environment that makes the film so enthralling to watch. In fact, I’m far from the first person to suggest watching it without subtitles and just drinking it in; it’s not as if the dialogue and voiceover narration adds very much.

Delta Space Mission was a big-screen spin-off from a sixteen-part animated series that ran on Romanian television from 1980 to 1983. In fact, in a tactic that recalls that used by Buster Keaton in 1923 with his feature debut The Three Ages (which was designed to be shown either as a coherent feature or three discrete short films), it was officially scheduled and budgeted as ten separate episodes, there being an official Animafilm policy against making feature films at that time. And, as co-director Călin Cazan explains in the on-disc interview, the fact that the feature was based on a very well-known TV series (at least locally) turned out to be very much to its advantage when it premiered. But, unlike a lot of feature-film spin-offs from pre-existing telly, no prior knowledge of the latter is required in order to appreciate Delta Space Mission – and there’s a lot to appreciate.

Sourced from a 4K scan of the original 35mm picture and sound elements and restored in-house by Deaf Crocodile’s Craig Rogers, Delta Space Mission looks incredible from start to finish. Any blemishes may well be inherent in the original production, and I’m glad that the restoration didn’t overzealously “correct” aspects such as marks on the original animation cels that betray their positioning relative to the background. Gratifyingly, the transfer also constantly reminds us that this originated on film – presumably very fine grain 35mm, as there’d have been no technical reason to use anything requiring lower-light sensitivity, but said grain is nonetheless reassuringly visible throughout. It’s framed in 1.33:1, which was overwhelmingly the dominant theatrical aspect ratio in eastern Europe until the fall of Communism a few years later, and there’s no compositional evidence that it should have been anything else. Most importantly of all, the colours are as mind-blowingly vivid as they were clearly always intended to be.

The soundtrack is presented as LPCM 2.0, and the music at least appears to be in stereo. Whether or not it was originally released like that in Romanian cinemas is an open question (Dolby Stereo was the then-dominant theatrical stereo system, and the logo doesn’t appear in the credits), but the production year certainly makes a stereo soundtrack a historically credible proposition. There were no issues with it technically – it’s hiss-free and with no other audible glitches or distortions.

Optional English subtitles are provided to translate the Romanian dialogue, and I didn’t spot any typos. While I’m not qualified to judge overall translation accuracy, it certainly seemed to fit occasional words that I recognised (“periculos” = “dangerous”) as well as matching the overall speech rhythms. Incidentally, the main title is presented onscreen in multiple languages – Romanian, French, English and Spanish – presumably to facilitate dubbing into these other languages without having to redo the opening titles, although this version only features the original Romanian audio.

Please note that in common with all Deaf Crocodile releases, this has been locked to Region A – and it duly refused to play in a Region B-only player.

Audio Commentary by Kat Ellinger

Like Samm Deighan on The Unknown Man of Shandigor, Kat Ellinger is usually a very safe pair of hands in the commentary department. She kicks off by describing the film as “trip-tastic”, and anyone familiar with her regular preoccupations won’t be too surprised to hear the words “gothic” and “fairytale” uttered early on (she elaborates on both later, citing Alma as an archetypal “maiden in peril”, albeit with rather more agency than most). She reflects on how eastern European animation differs from its western counterparts, tending to be both more adult-oriented and taken more seriously by critics, and although she admits that Delta Space Mission is more overtly child-friendly in a rather Hanna-Barbera way, it also has plenty of surprisingly grown-up elements. She also notes the visible influence of the great Russian animator Lev Atamanov (whose classic 1957 The Snow Queen (Snezhnaya koroleva) is an upcoming Deaf Crocodile release) as well as the inevitable Walt Disney – Tin in particular being a classic “Disney” comic-relief sidekick. She offers a useful potted history of Animafilm and Victor Antonescu’s output, before discussing Delta Space Mission’s relationship to Mihau Eminescu’s 1883 poem The Morning Star (Luceafărul) and analysing the film’s own imagery with lots of spin-off references to everyone from John Milton to Angela Carter to Hayao Miyazaki, whose films also have strong female protagonists – as do Joe d’Amato’s Black Emanuelle films, come to that. A couple of minor quibbles: Romania wasn’t a Soviet satellite when the film was made (it had declared independence two decades earlier), and the late, great animation historian Giannalberto Bendazzi was definitely not female (I’ve met him!) – but neither of these is serious enough to invalidate her arguments elsewhere, and the fact that she’s used Bendazzi as a source is otherwise a plus. And her enthusiasm is, as ever, infectious throughout.

Delta Space Mission TV episodes (14:45)

As mentioned above, Delta Space Mission was made in the wake of a sixteen-part animated television series, two complete episodes of which are included here – the first, Planet of the Oceans (Planeta oceanelor, 1980) and the third, Failed Towing (Recuperare ratată, 1981), both directed by the project’s originator Victor Antonescu. The lack of the original episode two in the middle doesn’t matter; each presents a discrete narrative.

In fact, because the main feature narrative is pretty episodic itself, there’s a lot to be said for watching these episodes alongside the main feature, padding the overall running time out to 85 minutes. It’s not possible to select individual episodes from the menu, but they have been individually chaptered so it’s easy enough to skip to the start of Planet of the Oceans.

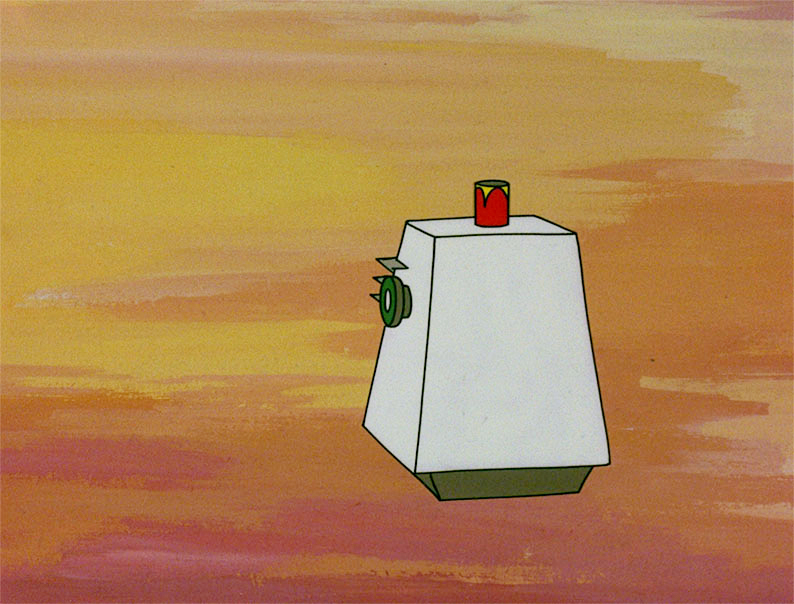

It might seem odd that Failed Towing has been programmed first, but this is presumably because in some ways it plays as a direct sequel to the feature, in that the Delta superbrain is already known to have malfunctioned, with consequences for Dan and Oana that begin with failure to dock with the space station and get worse from there. Fortunately, there’s a nearby planet to land on, a rather more barren and rocky affair than the lush and verdant one in the feature, complete with evidence that it’s already inhabited, thanks to some gigantic footprints – or, more accurately, clawprints. The cute robot sidekick this time is called Roby, a purple R2-D2 variant with a similar vocabulary of bleeps and electronic chirrups, who correctly identifies the footsteps as those of Tyrannosaurus rex – and when Oana encounters a real-life example, she realises that the planet is Earth, but in the Jurassic era, and that there are other dinosaur species out there too, a swooping Pteranodon being just as potentially lethal. But it’s all wrapped up very quickly, to meet the requirements of an eight-minute television episode.

There’s another electronic malfunction in The Planet of the Oceans, this time in the form of an exploration robot that has started to behave erratically, to the point of attacking Dan and Oana’s spaceship and sending it spiralling down to crash on the planet of the title. This time, the design bears a much stronger resemblance to the one in the feature, its oceans populated by amoeba-like creatures that can seemingly eat – or at least break down – anything, perhaps not an ideal position for our intrepid heroes to be in when these creatures are considerably larger than they are. One ingests the spacecraft (including Oana), the other ingests Dan, and while this makes for some highly striking imagery it also puts them at considerable peril, although thankfully for their physical and psychological wellbeing it’s also resolved within the allotted timeslot. As in Failed Towing, the brevity means that there’s not much room for narrative or character development, but Antonescu crams in an impressive number of eye-catching visuals along the way.

To my very pleasant surprise, the episodes were also presented in 1080p and have both been restored to the same technical standards as the main feature. Indeed, the only evidence that they’re not part of the same film is that the rough edges are more visible, a by-product of insanely fast production schedules. The subtitles, too, are fully up to the standards of those accompanying the main feature – I can forgive the unconventional spelling “Tyranosaur” because that’s consistent with the text that appears onscreen as part of the animation artwork.

Interview with Călin Cazan (41:34)

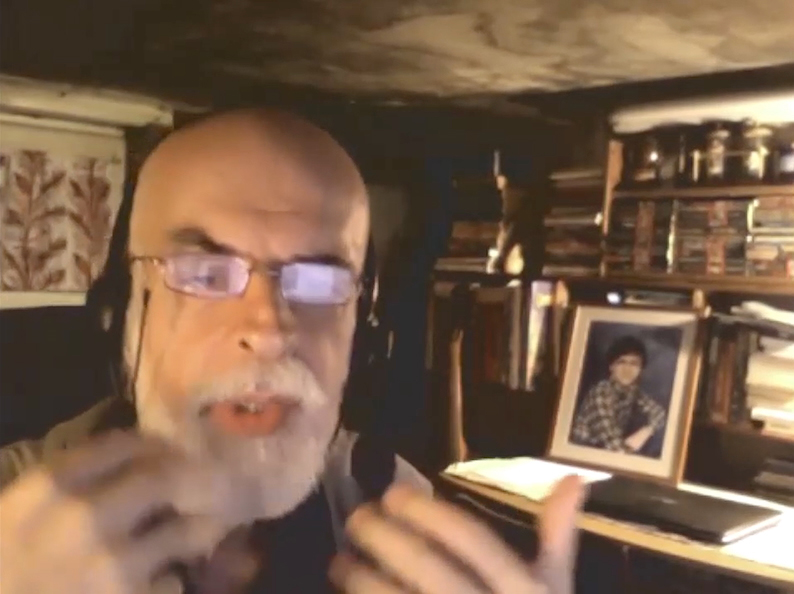

Given that boutique video labels – especially niche-audience ones like Deaf Crocodile – are usually labour-of-love shoestring operations, the availability of cheap high-definition cameras and editing tools has been a godsend when it comes to producing surprisingly high-quality extras on comparatively tiny budgets. But things changed abruptly in early 2020, when for health’n’safety reasons that could hardly have been more fundamental, interviewing people in situ became near-impossible (especially if they were elderly), and the most effective workaround was to do it over Zoom, Skype or a similar video-telephony service. Unsurprisingly, this led to a marked drop in technical quality (even if the interviewee had a 4K webcam and a fast broadband connection), but people accepted this because the only alternative was no video interview at all. Happily, this widespread acceptance also opened up the possibility of being able to directly interview people based on the other side of the planet without going to the usual lengths of flying to them (at considerable expense) or hiring a local camera crew and giving them a list of questions (at lesser but still noteworthy cost), which is why Deaf Crocodile’s much more recent post-lockdown releases are still doing it.

Delta Space Mission co-writer/director and lead animator Călin Cazan

Which lengthy preamble is to explain why this fascinating conversation between Deaf Crocodile co-founder Dennis Bartok (based in Los Angeles) and Delta Space Mission co-writer/director and lead animator Călin Cazan (based in Bucharest) is decidedly low-resolution on both the video and audio front. But I had no problem tuning this out – Cazan speaks excellent English, and he’s always perfectly easy to follow. In terms of his primary influences, it’s always interesting hearing about what was available behind the old Iron Curtain (in Cazan’s case, Chaplin, Disney and Hanna-Barbera as well as Russian and Bulgarian animation), and no less so hearing about how difficult it was to get an animated feature off the ground at a time when such things were genuine rarities thanks to the unavoidable time and expense needed.

He also discusses direct inspirations for the film (2001: A Space Odyssey, the above-mentioned Romanian poem The Morning Star), production and design logistics from initial sketches to storyboards to fully filled-in cels, and the way that Cazan and his late co-director Mircea Toia’s backgrounds helpfully complemented each other (Toia’s being in cinematography) – and he devotes several minutes to discussing the music. Cazan also steps back to discuss working at Animafilm in general, saying that working under Communism made little apparent difference to him personally (“maybe the salary”), mainly because studio head Lucia Olteanu fought any necessary political battles on their behalf, shielding them as much as possible. He also talks about his post-Communist experience of briefly working in the US – his dream was to work for Disney, but he didn’t know who to contact – but back in Romania he branched out into animating for videogames, which increasingly became his speciality, adjusting medium (PC, console, iPhone) where necessary. And he is, unsurprisingly, delighted about the film’s restoration and revival four decades later.

Booklet

The 8-page booklet mostly comprises the essay ‘Delta Dawn: The Launch and Trajectory of Delta Space Mission’ by writer, comic-book artist and regular Deaf Crocodile contributor Stephen R. Bissette. He delves into the film’s production history, and includes the interesting revelation that Animafilm founder Victor Antonescu was more of an old-school animator than his colleagues, and wasn’t a fan of the film’s ultimate “trippy, Yellow Submarine vibe” – although Bissette is surely right to suggest that this is a key aspect of its present-day international appeal.

As with Deaf Crocodile’s first release, The Unknown Man of Shandigor, a superlative presentation of a fascinatingly unusual main feature has been accompanied by intelligent quality-over-quantity extras that cast valuable light on areas barely touched on by English-speaking commentators in the past. While Fantastic Planet and Yellow Submarine remain the defining examples of psychedelic European feature-length animation, it’s far more likely that fans of those will enjoy Delta Space Mission than otherwise. Terrific stuff – and I note with keen anticipation that Deaf Crocodile has since released another Călin Cazan/Mircea Toia feature, The Son of the Stars (Fiul stelelor, 1988), which I’ll be reviewing here in due course.

|