|

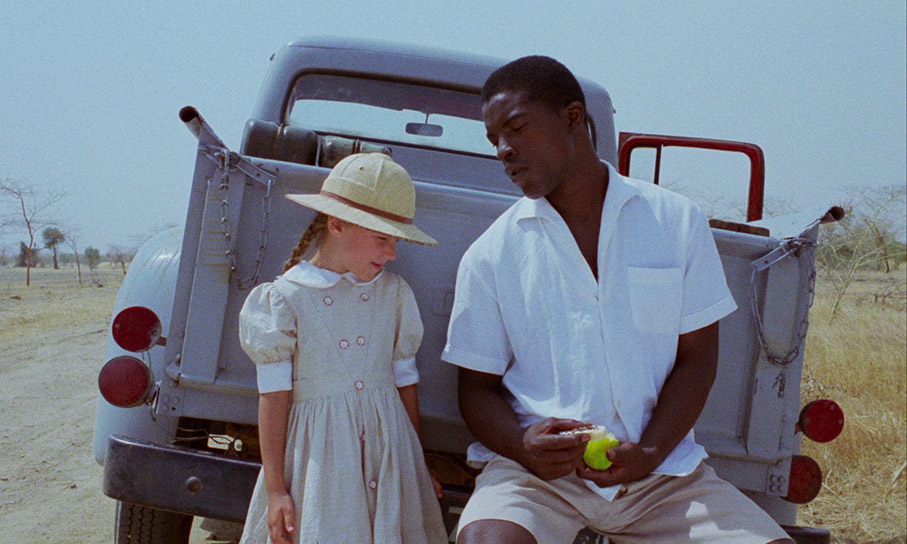

Cameroon, the 1980s. A young woman, France (Mireille Perrier), returns to the country where she grew up. Hitching a lift from a local and his son, she talks to them and at one point takes out an old journal. At that point, we flash back to the 1950s. This is conveyed by a hard cut, though we have a visual jolt due to the visual palette changing, from greens to sunbaked yellows and browns, and I suspect a change of a filter on Robert Alazraki’s camera. A much younger France (Cécile Ducasse) is the only child of regional administrator Marc Dalens (François Cluzet) and his wife Aimée (Giulia Boschi). Left much to her own devices, France befriends the houseboy Protée (Isaach de Bankolé) and observes the interactions of her parents with their servants and the native Africans nearby, including a possible sexual attraction between Aimée and Protée.

It probably doesn’t need saying that Chocolat should not be confused with other films with the same title, such as the 2000 film directed by Lasse Hallström and starring Juliette Binoche and Johnny Depp from the novel by Joanne Harris. Chocolat, made in 1987 and premiering at Cannes in 1988, was Claire Denis’s first feature film as director. She had been working as an assistant director (for Wim Wenders on Paris, Texas and Wings of Desire and for Jim Jarmusch for Down by Law, amongst others) when she began work on the script, which she wrote with her regular collaborator, on ten films to date, Jean-Pol Fargeau. This was the only one of Denis’s films that Robert Alazraki shot, but the camera operator, Agnès Godard, later became Denis’s regular cinematographer.

Chocolat sets a template for much of Denis’s work. It cries out for an autobiographical interpretation: Denis, born in 1946, was the daughter of a French colonial civil servant (though not an only child) and spent her childhood in French West Africa, in the then Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso), Cameroon, the then French Somaliland (now Djibouti) and Senegal. Add to that, the fact that Mireille Perrier physically resembles Denis. However, while the majority of the film’s running time is presented as a flashback framed by the adult France, who is an observer of the action, there’s a sense that the film has France as much at a distance as everyone else, and while we observe her she is often opaque and perhaps Protée is as much at the centre of this film as she is. If you read the film as an allegory of relations between France the coloniser and Cameroon the colonised and soon to become independent, this is played out more between Protée and Aimée rather than her symbolically named daughter.

I saw Chocolat in the cinema on its UK release, and my memories are more of an overpowering sense of atmosphere and place than of a storyline. I’d add to that Abdullah Ibrahim’s score. Denis has frequently favoured mood and character nuance over more conventional story dynamics, with narrative progressions sometimes quite elliptically conveyed with what would in other hands be determined plot beats deemphasised. There are hints of events happening offscreen and almost out of sight, and plenty of undercurrents. While the attraction between mother and houseboy is palpable, we don’t know if it remains as tension or is ever consummated. Denis was asked to make this clear and to film such a consummation scene, but refused.

Ivoirian actor de Bankolé became a Denis regular. He played the lead in her next film No Fear No Die (S’en fout la mort, 1990 – shown at the London Film Festival, where I saw it, but never released in the UK as it would almost certainly have to be cut due to the portrayal of its subject matter, illegal cockfighting) and played a key role in Jim Jarmusch’s Night on Earth. Denis and Alazraki’s camera certainly observes him, with Denis’s notable eye for male beauty well in evidence. The film begins with the adult France gazing at the man who is later to give her a lift, bathing in the sea with his son. Much has been written about “gaze” in cinema, in the sense of the camera in the place of the spectator gazing at an object of desire. That gaze is usually assumed to be male and heterosexual, with films like Denis’s later Beau travail (seventh place in Sight & Sound’s 2022 Greatest Films of All Time poll), which gaze at men in this way, often described as homoerotic when they are actually female-heterosexual. Chocolat is a fine evocation of a time and a place, and an auspicious debut for one of the current cinema’s leading directors.

Chocolat is released by the BFI on Blu-ray, a disc encoded for Region B only. The film begins with an advisory notice from the BFI that it contains racist dialogue. Chocolat had a 15 certificate on its cinema release, likely (from memory) because the 12 did not exist at the time. However, on VHS in 1992 it was rated PG. Now, with a resubmission to the BBFC, it is 15 again. The issue is with language, or rather the differing subtitling of it: not just the two racial slurs referred to in the advisory, but one use of “motherfucker”, which is an instant 15 by current BBFC standards. If “salaud” had been more usually translated as “bastard”, the film would be a 12, not that it would likely have any appeal to anyone young enough for that to make a difference. As a documentary, Childhood Memories has been exempted from certification but contains nothing untoward.

The film was shot in 35mm, on now-obsolete Agfa colour stock. The Blu-ray transfer is from a 4K restoration approved by Denis and Alazraki and is in the original aspect ratio of 1.66:1. Denis has declared herself very satisfied with this restoration, and you can see why. It does look like my memories (albeit over thirty-five years) of seeing this on a 35mm print in the cinema in 1989. The transfer is sensitive to the changes of colour palette, which largely come across to the different ecologies of parts of Cameroon, lush greenery here, sunbaked yellows, browns and greys there. Grain is natural and filmlike. I can’t fault this.

The soundtrack is the original mono, rendered as LPCM 2.0. The dialogue, music and sound effects (including ever-present insects) are well-balanced. Optional English subtitles for this mostly French-language film are optionally available. Some dialogue in Hausa and Arabic is intentionally left unsubtitled, but there are no hard-of-hearing subtitles available for a small amount of dialogue in English. Hard-of-hearing subtitles are available for the Q & A and Childhood Memories among the extras.

Commentary by Kate Rennebohm

This is a new commentary by film critic and scholar Rennebohm. It’s detailed and highly scene-specific, but stays the right side of simply describing what is on screen. She does tackle the not-infrequent accusation of political incorrectness that Denis has faced, by being a white woman often dealing with non-white characters, sometimes in African settings. She also points out something that I hadn’t spotted: one of the luggage handlers at the very end is played by Isaach de Bankolé, though Denis did not intend to suggest that he is actually Protée. A useful commentary, but rather too often Rennebohm says that she can’t recall some detail or name offhand, which suggests that this could have been edited to include that information rather than the present moments of vagueness.

Claire Denis à propos de Chocolat (18:10)

Recorded in 2023, Denis, seemingly in her own kitchen, talks about her debut film. Her addresses to camera alternate with extracts from Chocolat. This item is divided into sections which have titles such as The Sensoriality of Landscapes in the Direction, but as another section is called The Story of the Ant Toast, it’s by no means as high-flown as that might sounds. Denis covers most bases, beginning with her work as an assistant director. She is clearly fond of the part of Cameroon where she grew up and where the film was shot, though nowadays it’s Boko Haram territory so a no-go area. She also gives an explanation of the title, which she says refers to a sense of being fooled and taken advantage of, so as likely a reference to Protée as much as anyone else, and not just to the colour of his skin. She also talks about the present 4K restoration.

Claire Denis in Conversation (48:47)

This took place in May 2019 at the BFI Southbank as part of a Claire Denis retrospective. The interviewer is Tricia Tuttle. Largely a career overview on Denis’s part, this begins with her breaking into the film industry as an assistant director, which enabled her to meet directors she later worked with, such as Jacques Rivette. She also appeared as an extra in a Robert Bresson film (she doesn’t name it, but it was Four Nights of a Dreamer from 1971). As an assistant director, she was often seen as a combination of American and European styles in that role: being a strict set-runner on one hand but an artistic collaborator with the director on the other. Denis does spend some time discussing Chocolat among her other films and, given the use of music in many of her films, is asked about her Spotify playlist. Music comes to the fore as she discusses her collaborations with the band Tindersticks, beginning with Nénette and Boni (1996). As usual with these Q&As, clips from films (here, Chocolat, 35 Shots of Rum and Trouble Every Day) are edited out and questions from the audience appear on screen as captions.

Trailers (3:15)

There are two, the 1988 original (1:37) and the restoration reissue (1:38). The former, very soft, is overtly impressionist with much use of superimpositions not actually in the film itself. The latter, with Denis’s stature long established, makes much of her previous distinguished work.

Childhood Memories (4:09)

Directed in 2018 for the BBC and the BFI by Mary Martins, who grew up in Lagos, this is an account of visiting her grandmother’s house, conveyed by means of stock footage, stop-motion and 2D animation. Engaging if very short, it’s an apposite companion piece for the main feature on this disc.

Booklet

The BFI’s booklet, available for the first pressing only, runs to twenty-eight pages. Following a spoiler warning, this kicks off with “The Shared Scar of Colonialism” by Cornelia Ruhe, which begins by placing the human body as central to Denis’s work. She also distinguishes between nostalgia for a colonial childhood and nostalgia for a colonial rule – the former may apply to this film but the latter does not. Both France and Protée bear a scar in the same place – we see this happen late in the film. This essay looks at Denis’s film through a colonial, and postcolonial, lens.

After a cast and crew listing, Catherine Bray is up with “The Magic of ‘The Meanest’”, the words in quotes being Denis’s own description of how she runs her set. Bray rightly sees Chocolat as setting out many of the themes and techniques of her work, and initiating many of her major collaborations, and continues with an overview of Denis’s career up to 2022’s Stars at Noon, her second English-language film (after High Life, 2018). Kevin Le Gendre follows with “A Solo Journey to Mindif”, which begins as an appreciation of Chocolat before concentrating on Abdullah Ibrahim’s score, which was released on a soundtrack album called Mindif. Ibrahim is a leading figure in contemporary jazz and Le Gendre pays much attention to his musical influences and instrumentation in Chocolat.

The booklet concludes with notes on and credits for the extras, including a piece by Mary Martins on her own film Childhood Memories.

Chocolat was an auspicious feature debut for someone who has worked prolifically since, proving herself one of the most distinguished filmmakers currently active. It is presented well on this BFI Blu-ray.

|