There are some spoilers ahead. If you don't yet know the film, you might want to hop forward to the technical specs. I'm not going to be specific about details but I do discuss the film's trajectory and how it seems likely it will end even if you're watching it for the first time. Another warning will appear when I get to the offending paragraph, which you can skip if you prefer.

There's something potent about urban legends, at least that's what I'm told. Where I grew up there were no such stories, no creepy house in which someone was reputed to have been horribly murdered, no tales of a mythical man-beast lurking in the local woods, no name you should not say out loud after dark when the moon is in its second quarter and there's an R in the month. I was never a superstitious person and from an early age realised such tales were claptrap anyway, and despite living in an area where you'd think they would flourish, even playground chatter never threw up a single supernatural story. Then again, you don't really need fake bogeymen when you live only a few short miles from the government's supposedly 'secret' nuclear bunker, and if the locals all knew about it then it seemed likely that the Russians did to, and we figured that if a third world war kicked off we'd be one of the prime targets. For me, that prospect was scarier than the idea of a shadowy watcher in the woods.

Every bit as sceptical about the authenticity of such urban legends but nonetheless fascinated by them and their origins is Chicago graduate student Helen Lyle, who in the film under discussion here is researching a paper on them. One such local story told to her involves a mystical figure known as Candyman, who legend has it can be summoned by saying his name five times into a mirror, which will prompt him to appear and take human life using a large metal hook embedded in his right arm where his hand used to be. Helen is working late one evening when a cleaner overhears her taped interview on the subject, and she and her colleague tell Helen the story of Ruthie Jean, a resident of the Cabrini-Green housing project whom they claim was killed by Candyman. Further research reveals that over twenty people have been violently murdered in the area over the course of past few years. Despite the Project's reputation as a gang-controlled no-go area, particularly for a middle-class white girl like Helen, she and her fellow student Bernadette decide to follow-up the story and visit the location of Ruthie Jean's murder. The still sceptical Helen, having already tempted fate by reciting the summoning ritual, then finds herself the target of the very subject of her research.

There's a subgenre of the horror movie – and it's here that I get into spoiler territory – that doesn't really have a name and probably doesn't even include enough films to even count as a subgenre at all, one whose downbeat tone makes it clear at an early stage that the central character is effectively doomed. Probably the most widely seen of these is David Cronenberg's 1986 remake of The Fly, whose lead character's fate is sealed from the moment the title creature makes its way into the pod with our lead character during his first experiment in human teleportation. In the 1992 Candyman, this conviction that things will not turn out well for its female lead hit me at a disarmingly early stage, and was confirmed beyond doubt shortly after Candyman puts in his first appearance. Now I realise I'm talking from the perspective of someone who has seen the film a number of times and that my memory has possibly been coloured by now knowing how the story plays out, but watching the film again for this review I was struck by the melancholic tone of even the early scenes and particularly the downbeat opening strains of Philip Glass's haunting score. Yep, Philip Glass. That Philip Glass. How many horror movies can boast a score by the master of modern minimalist music? (Mind you, having delivered the score, Glass apparently hated the film when he first clapped eyes on it, a viewpoint that has since mellowed and he has even become good friends with its director.)

On paper, at least, Candyman has all the signs of a by-the-numbers horror flick of the sort that were ten-a-penny back in the 1980s and even into the early 90s. Think about it for a second. An attractive young woman learns of a deadly urban legend and instead of steering well clear of the location in which it is centred, she heads straight there, putting herself in peril, and does the very thing that the legend warns you should never do. We even have a demonic monster in the shape of Candyman himself, a towering figure with a bloody hook for a hand and a voice so deep and resonant that even his whispers seem to be emanating from the bowls of hell. But Candyman is no cheapjack slasher tale, having originated as a short story titled The Forbidden in the celebrated Books of Blood by British horrormeister Clive Barker and been adapted and directed by his countryman Bernard Rose. Rose, it should be noted, had already made a distinctive mark on the horror genre with the atmospheric and unsettling Paperhouse, an 1988 adaptation of the novel Marianne Dreams by Catherine Storr. I could talk more about this film and why my initial response to it has altered over the years, but that is probably a story for a later Blu-ray release. Sounds like a perfect Arrow title to me.

But I digress. We're clued in from the classy opening titles – which mechanically drift in and out of frame over a top-down view of Chicago streets and buildings that could almost have found a place in Godfrey Reggio's Koyaanisqatsi – which was also distinctively scored by Philip Glass, of course – that this is not going to be a run-of-the-mill genre movie. This is emphasised by the fact Helen is an adult graduate student rather than the usual reckless teen, one whose educator husband Trevor appears to be tolerant rather than supportive of her work and who is having a not-too-subtle affair with one of his younger female students. The decisions Helen makes are all contextually plausible, driven as they are by her intense interest in her chosen subject and a determination to deliver a thesis that will exceed the expectations of her smug professor. When she proposes a visit to Cabrini-Green estate, a real-world housing project with a fearsome history of violent crime and extreme poverty, Bernadette rightly questions the wisdom of doing so, but Helen's counterarguments are equally persuasive, as she attempts to downplay the risk by advising her friend to "dress conservatively" in the hope that they will be mistaken for police and allowed to go about their business unmolested.

The best horror films usually have a socio-political subtext and in Candyman it's not only interwoven into the narrative but grounds the fantasy elements in a tangible reality, which in turn brings a very real tension to scenes that might otherwise feel too abstracted from our own experience to build the necessary tension. Thus, while Candyman's lair is as gloomy and ominously decorated as a vampire's cave, locating it in an abandoned apartment in a run-down, graffiti-plastered tower block patrolled by gangs gives it an air of tangible danger that most of us can relate to. As Helen and Bernadette make their way into the building in question and are approached verbally hassled by a group of youths, it's easy to empathise with their discomfort, and when Helen leaves Bernadette alone in the remains of Ruthie Jean's apartment to go exploring, the tension created comes not from worrying about the prospect of Candyman putting in an appearance but the fear that the women will be jumped by the gang on whose territory they are precariously trespassing. These two elements later collide when Helen returns to Cabrini Green to investigate further and is confronted by a gang leader who trades on local belief in the Candyman legend by adopting his moniker and brandishing a longshoreman's hook, which he uses to violently beat Helen around the face in the Chicago equivalent of Trainspotting's Worst Toilet in Scotland.

As Helen soon discovers, however, Candyman is not a superstition onto which the poor and disenfranchised project the horrors of their daily lives as she earlier speculates, but a genuine supernatural entity, one that can indeed be summoned in the manner prescribed by the legend. We're well into the film before Candyman appears, and when he does so he kicks against tradition by doing so in daylight, and instead of slaughtering Helen as expected he sets about utterly destroying her life. This is instigated by this film's fly-in-the-teleportation-pod moment, when Helen wakes, covered in blood, from her hypnotic first encounter with Candyman in the apartment of kindly Cabrini-Green resident Anne-Marie McCoy, to the sound of Anne-Marie's traumatised screams. Anne-Marie's dog has been decapitated and her baby missing and its crib splattered with blood. The distraught Anne-Marie is convinced that Helen is the perpetrator, a view shared by the police when they burst in to find Helen defending herself from Anne-Marie's fury with the meat cleaver we can presume was used to slaughter the dog. Watch this scene once and the implication is clear, that Candyman has killed the animal and taken the baby and left Helen in the apartment to take the blame and face the terrible consequences. But watch it again and an alternative reading presents itself, that Candyman is a figment of Helen's delusion and that she did indeed commit the crime in question, and that she doesn't wake but emerges from a psychotic trance. Working in favour of this reading is the fact that we are not witnesses to the crimes in question, just their bloody aftermath, and that Anne-Marie seems so certain that Helen is the perpetrator and not a near-victim of heinous acts committed on a housing project with a reputation for violent crime. This is underscored later when Candyman appears to Helen but is not present on a video recording of the encounter, but doubt is then cast on this reading when Helen summons him again and he frees her by tearing her guardian apart and undoing restraints that she would have been unable to loosen herself. Speaking personally, I find the prospect that Candyman exists and develops a strange bond with Helen a lot more appealing than the "it's all in her mind" alternative, so I'm going with that.

The racial subtext that Rose bought to the film in his adaptation is clearly evident without being overstated, though can feel a little undercooked and just a tad white-centric when compared a more recent work like Get Out. Here, white, well educated, middle-class Helen takes an academic interest in legends born in a world of extreme poverty and superstition populated exclusively by people of colour, where she sticks out like a sore thumb, is assaulted by a black gang and is terrorised and even seduced by an imposing black monster. Some balance is provided by Anne-Marie, who though trapped by poverty in Cabrini Green has contempt for the gangs and is steadfast in her refusal to be dragged down to their level and her determination to do right by her young child. Bernadette, meanwhile, serves to remind us that societal divisions are fuelled as much by class as race, as despite her dark skin is as painfully out-of-place at the Cabrini Green project as Helen. None of this, however, is superficial decoration, as race and the consequences of racial hatred prove to be central to both Candyman's backstory and why he toys with and even romances Helen instead of mutilating her as he is reputed to have done with others.

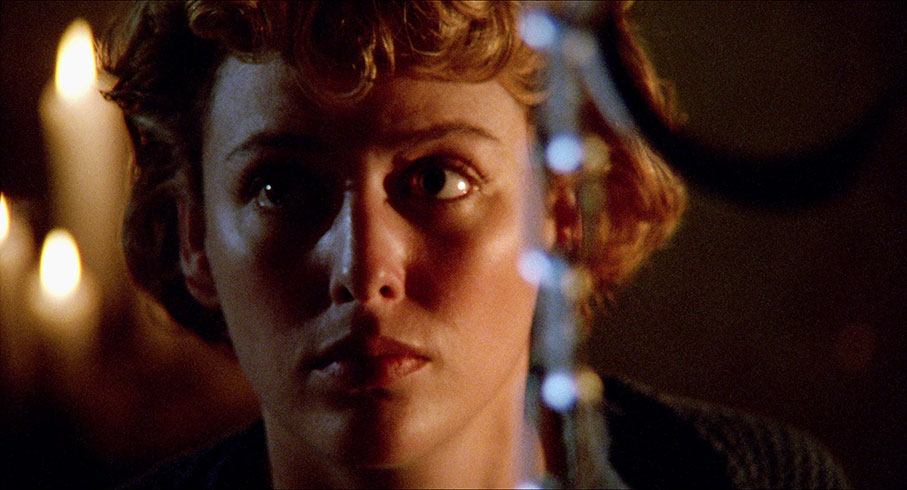

It all works sublimely. In adapting the short story by Clive Barker, director Rose has built intelligently on already solid foundations, and as a director understands so much better than many wannabe genre filmmakers when to show restraint and when to shock or startle, as well as the considerable value in taking time to establish character and situation before fully engaging with the horror. He also knows how to cast a horror movie, not with generic teen faces with health-club bodies and barely functional line delivery skills, but with actors of real talent who commit themselves to their roles and treat the project as seriously as they would a prestige drama. Leading the way here is Virginia Madsen, who from the off completely convinces as Helen and litters her performance with lovely little touches that sell even potentially credibility-stretching developments as real, from the playful lean forward towards the mirror to deliver the fifth and final "Candyman" to her heart-rending distress at being ordered to strip by a coldly observant female police officer after her arrest. As Candyman, Tony Todd was inspired casting in a role that really helped to put him on the map, his commanding voice and Shakespearean delivery transforming his whispered warnings and proclamations to Helen into darkly seductive poetry. And how many actors would agree to do a scene that required them to have live bees crawling around in their mouth? There's fine work, too, in the supporting roles, with Xander Berkeley at his slimy best as Helen's cheating husband Trevor, while as Bernadette, Kasi Lemmons makes for an instantly likeable best friend to the heroine, a role she also played the previous year in The Silence of the Lambs. I'll also give a small shout for Carolyn Lowery as Stacey – the student with whom Trevor is having an affair and later moves in with – for her shocked reaction to Helen's unexpected reappearance, which differs significantly from the movie norm but feels utterly authentic and not at all 'performed'.

It's been some years since I last saw the film and I was genuinely thrilled by how well it still stands up, and know that I'm not making allowances here – even stood against the finer horror works of recent years, Candyman could hold its own and then some. Jane Ann Stewart's stellar production design and Don't Look Now lensman Anthony B. Richmond's handsome cinematography and use of slow and steady camera movements (no frenetic waggle-cam here) help build an atmosphere of oppressive dread, and Philip Glass's score is one of the most hauntingly beautiful in horror film history and has been stuck in my head since I re-watched the film. But in the end it's Rose's show and he works some dark wonders here and shapes his material into a film that stands tall as one of the most accomplished, involving and satisfyingly complete works of late 20th Century horror cinema.

A consistently handsome 1.85:1 transfer that captures the carefully composed and lit but realistic gloom of the urban and municipal interiors and the demonic darkness of Candyman's lair without losing crucial detail. Contrast is well balanced and the colour is generally naturalistic – brighter colours sometime pop when they do appear, but are never over-saturated and there are no compression issues on rare areas of single bright colours (the vivid blue sky when Helen walks across the university campus, for example). Detail is crisp and there is a fine film grain throughout, and almost all traces of dust and damage have been removed. This is a fine restoration and a top-notch transfer.

When it comes to the soundtrack, you can choose between Linear PCM 2.0 stereo and DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround, and while both are crystal clear, cleanly mixed and free of damage, the 5.1 really comes into its own with the organ-like bass notes of Philip Glass's score and the reverberating boom of Candyman's voice.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are available.

It should be noted that two edits of the film are included in this package, the American R-rated cut – which as far as I am aware is the one that has appeared on all previous DVD releases – and the original UK cut. Curiously, both run for 99 minutes and 17 seconds, yet the UK version includes two extra shots of violence and blood spattering during the sequence in which a psychiatrist is killed. I have to presume those few extra seconds have been lost elsewhere, something that may be confirmed in the booklet that accompanies the retail version, but I don't have that yet.

Audio Commentary with Bernard Rose and Tony Todd

The first of two newly recorded commentaries features writer-director Bernard Rose and Candyman himself, actor Tony Todd, and despite only intermittently being screen-specific, it's an absolute blast from start to finish. The two men clearly get on famously and have plenty of fond memories of the shoot, but take diversions to discuss the merits or otherwise of Avengers: Infinity War and A Quiet Place (which Todd loves but whose logic problems proved a barrier for Rose) and for Rose to praise John Carpenter's Halloween as "as pure a masterpiece as the genre gets" and express complete disinterest in seeing the new one. Rose's description of the extraordinary climactic scene of the Candyman sequel he was unable to sell to studio execs made me wish someone would give him the money to make it right now, and he salutes Clive Barker's original short story and highlights elements that he kept from it and built on. There's some detailed discussion on the film's strong socio-political elements, the perils of extreme fame, the depressingly high number of low-quality horror movies, today's mobile phone culture, and so much more. It ends on an amusingly boisterous note, with Todd jokily protesting that he's given Rose "90 minutes of my time on a Saturday that is filled with sports possibilities" and that he is now "going home and crash and get on my couch and maybe play God of War." How could you not love this man? A terrific listen.

Audio Commentary with Stephen Jones and Kim Newman

I'd have been happy enough with one great commentary track, but Arrow has gone the extra mile here and delivered two. The second, by the ever-reliable team of genre enthusiasts and writers Stephen Jones and Kim Newman, is every bit as good as the first and different enough in tone and content to avoid repetition and make this as essential a companion to the film. Both Newman and Jones are big Candyman fans and do a fine job of analysing and highlighting its specific qualities, from the savvy casting and strong lead performances to its serious approach, its downbeat tone, and its potent socio-political undertones. They discuss the genre writers who emerged in the wake of the success of Clive Barker's Books of Blood, the impact of casting a Shakespearean actor as the film's bogeyman, and there's an interesting musing on the differences between US and UK censorship of horror movies and how the target audiences differ in the two countries. There's loads more here, all of it enthralling, and Newman leaves us with an interesting thought when he suggests that the film works because it makes us afraid of ourselves rather than ‘the other', a potent message in these times of increasing intolerance and prejudice.

Be My Victim (9:46)

A welcome interview with actor Tony Todd, who recalls landing the roll of Candyman, working with Bernard Rose to define the character, the casting of actual Cabrini Green gang members in small roles in the film, working with real bees and more. He describes Rose as "one of the most intelligent directors I've ever worked with" and still holds the film in very high regard.

It Was Always You, Helen (13:10)

An interview with lead actor Virginia Madsen, who reveals that she was cast as Helen after Bernard Rose's actor wife Alexandra Pigg had to pass on the role after becoming pregnant. She also surprised the hell out of me with the news that she is allergic to bee stings, which added an extra level of risk to the scene in which she had to have them crawling over her face, which she remembers as being a pleasant sensation. She recalls Rose excitably calling for more blood, being hypnotised for the scene in which she falls under Candyman's spell, and that the first thing that you noticed about Tony Todd was his extraordinary voice and that he was "quite beautiful." She remains very happy with the film and describes it as "one of the best experiences that I've had."

The Writing on the Wall: The Production Design of Candyman (6:21)

Production designer Jane Ann Stewart talks about basing her work on the film on reality and provides some interesting specifics about the design of Candyman's Lair and the bonfire for the climactic scene. She also, like seemingly everyone who worked on the film, is proud of what she and her colleagues achieved.

Forbidden Flesh: The Makeup Effects of Candyman (8:01)

Makeup artists Bob Keen, Gary J. Tunnicliffe and Mark Coulier outline the process of creating fake faeces to smear on the wall of the worst toilet in Chicago, constructing Candyman's decaying chest and the plate worn by Tony Todd to allow him to have live bees placed in his mouth. I still can't believe he had the balls to do that. The best story involves their thwarted effort to get a hook forged by a real blacksmith, but I'll let you discover that one for yourself.

A Story to Tell: Clive Barker's ‘The Forbidden' (18:38)

Writer Douglas E. Winter, whose books include Stephen King: The Art of Darkness – the Life And Fiction of the Master of the Macabre, recalls being introduced to Barker's Books of Blood in manuscript form by an enthusiastic Ramsey Campbell, and highlights the differences between Barker's short story The Forbidden and Bernard Rose's film adaptation. He's a big fan of the film and points out how rare it is for a horror movie to live up to its literary source, and finishes on a story of how Barker inspired him in his personal life.

Urban Legend: Unwrapping Candyman (20:40)

Writers and genre fans Tananarive Due and Steven Barnes examine Candyman from a black perspective, and it's a fascinating discussion, with both participants making excellent points and Barnes providing a detailed and perceptive breakdown of some key horror tropes and how they relate to real-world fears. They're both huge fans of the film but also highlight elements that would probably be rethought if it was remade today, and they made a good case for why having diversity behind the camera is every bit as important as diversity in the characters and casting. It's the sort of smart, enthusiastic and animated debate that part of me wishes that I could participate in, even though I secretly know that I'd soon find myself out of my depth. An excellent extra.

Theatrical Trailer (2:04)

"From the mind of Clive Barker..." How many genre writers' names can be used to headline a trailer for a film based on one of their short stories? It's slickly assembled, sure, but when the score for the film itself was composed by Philip Glass – Philip Glass! – why the hell would you swap that for a synth track that sounds like an rejected take from Trevor Jones' score for Mississippi Burning?

Image Gallery

38 slides of promotional stills, posters, press material and video covers.

Bernard Rose Short Films

A Bomb with No Name on It (1975) (3:40)

Ah, the wave of nostalgia that hits me when I see opening titles made from cut-out letters on a textured background. The story here is simple – a respectable-looking man conceals a bomb in a briefcase and leaves it in a café to indiscriminately kill the other patrons. This one struck a particular chord with me because of its eerie similarity to a short film I wrote (but someone else got to direct – those are the breaks) in my film school days just three years after this was made, though mine had dialogue and none of those film's overt climactic symbolism. I have a feeling Mr. Rose and I were taking inspiration from the same news stories of the day.

The Wreckers (1976) (5:58)

While a middle-aged bourgeois couple attend a dinner part with similarly well-to-do friends, their son throws a bash of his own at their house, then learns that there are more societal divisions than the generation gap when the party is invaded by a group of four council estate thugs, who wreck the house and violently assault the partygoers. Social politics explored with sledgehammer subtlety and no real depth, but the filmmaking is solid and there's a neat use of cross-cutting between the locations.

Looking at Alice (1977) (27:24)

A lonely young man obsesses over the flirty young model who lives in the building opposite, but fails to realise that she is dealing with anxieties of her own. The longest of the films here is probably the most developed and technically accomplished. Shot in black-and-white, it has the feel of a student production (I saw and even shot enough of these in my film school days to recognise the signs – the sound recordist even makes an unscheduled appearance at one point), with some meandering in places and sudden and kinetic explosions of experimentation elsewhere. The influence of the Nouvelle Vague and even at one point Performance is keenly felt, but there are also a couple of editing techniques explored here that would make their way into Rose's later work.

The Cinema of Clive Barker: The Divine Explicit (28:09)

A welcome interview with genre author and filmmaker Clive Barker, who these days has the look of a man who has graduated with honours from the Keith Richards school of rock 'n' roll ageing, but is still one of the smartest and most erudite ambassadors for the genre. He talks about being drawn more to writing than filmmaking as a young man, but has nothing but positive memories of shooting Hellraiser and intriguingly defines these two different forms mof creative expression by telling us, "Writing is masturbation and filmmaking is an orgy." He's disarmingly open about his difficult relationship with his father and his discomfort at having to reveal to him that he was gay, and has some typically insightful things to say about the horror genre, pointing out that even when we watch horror movies with friends, we tend to experience them alone. I was happy to hear that he has a high opinion of Candyman, and his story of attending autopsies and his joyous response to holding a man's brains in his hands is intriguing. He also neatly sums up his sympathy with movie monsters by revealing that "I'm attracted to the philosophy of darkness."

Also included with the retail release is a fully illustrated collector's booklet featuring new writing on the film by festival programmer Michael Blyth, 6 lobby card reproductions, a reversible fold-out poster featuring two artworks, and a limited edition perfect-bound booklet reproducing the original hand-painted storyboards by Bernard Rose, but these were not available for review.

A still-superb horror work from a decade that was not exactly resplendent with them, handsomely restored and transferred, and boasting a treasure-trove of terrific special features, including physical extras exclusive to this Limited Edition (mine's now on order). This review is late due to personal circumstances, and I'm not actually sure how many units there will be in this limited run, but knowing how quickly Arrow's special editions sell, I'd get your hands on this one before they all disappear and become collector's items. Highly recommended.

|