Farewell to sadness

Sadness hello

You are written in the lines of the ceiling

You are written in the eyes that I love |

from the epigraph of the novel, from Paul Éluard’s

poem La vie immédiate, translation by Heather Lloyd |

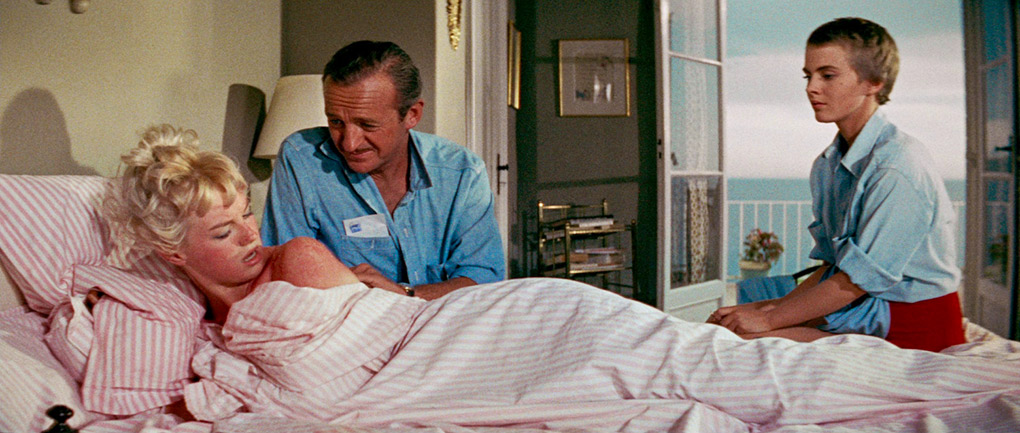

Paris, the later 1950s. Cécile (Jean Seberg) lives with her widowed father Raymond (David Niven). She lives a high life of dances and boyfriends, but ennui has set in and she wonders if she might feel happiness again, following what happened a year before in summer on the Riviera. Then, she and Raymond were staying with his latest mistress Elsa (Mylène Demongeot). Cécile meets law student Philippe (Geoffrey Horne), also on holiday. Then Anne (Deborah Kerr), a friend of Raymond’s late wife visits. Disconcerted to see an attraction bloom between Raymond and Anne, Cécile intends to do something about it.

Bonjour Tristesse was a likely sure thing in 1958: an adaptation of a fashionable and then somewhat scandalous novel, written by a woman not much older than her heroine, with a rising star in the lead, her later troubles not then common knowledge. It was a colour and CinemaScope production making good use of the locations of the French Riviera, somewhere the majority of the audience would not have much chance to visit in person. With gowns by Givenchy, jewels by Cartier and accessories by Hermès, it gave many of those cinemagoers a taste of a high life they would almost certainly never experience themselves. While the film did well enough at the box office, it was a critical disappointment. However French critics, such as future directors François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, were exceptions to this. The latter hailed the film as one of the ten best of 1958 and cast Jean Seberg, with the same fashionably short hairstyle, in his debut feature Breathless (A bout de souffle) two years later.

Bonjour Tristesse was first published in France in 1954, to no small attention due to the fact that its author Françoise Sagan (Françoise Delphine Quoirez, 1935-2004) was all of eighteen, a year older than Cécile. Like her protagonist she was an indifferent schoolgirl, expelled from one establishment and failing her baccalauréat at the first attempt. She passed it on the second go and went to the Sorbonne in 1952, but did not graduate. However, by then she had a best-selling novel to her name, which she had written in two to three months. Sagan had been a wide reader from a young age, and took her pen name from a character in Marcel Proust’s A la recherche du temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time, originally translated in to English as Remembrance of Things Past). The novel is a short one, which could fairly be called a novella: 100 pages in the edition I read, around 30,000 words at my estimate. Bonjour Tristesse also attracted comment for its sexual content, particularly its implication that a teenage girl could have sex with a boy – Cyril in the novel, Philippe in the film – with no especial consequences. The novel is not explicit at all, certainly not nowadays, but the Vatican condemned it as “poison that must be kept away from young lips”. The original English translation by Irene Ash, published in 1955, was a bowdlerised version which also removed some of Cécile’s philosophising. This edition was superseded in 2013 by a new and complete and unexpurgated translation by Heather Lloyd, which is available in an omnibus edition with Sagan’s second novel, the equally short and somewhat franker A Certain Smile (Un certain sourire). This was filmed in 1961 after significant changes to the story enforced by the Production Code Administration (PCA).

Sagan’s novel could quite easily today be published as young-adult, not just for Cécile’s youth but for that of her author. A modern YA novel could go much further with the sexual content than Sagan did. However, there is a difference in tone between Bonjour Tristesse and a lot of YA fiction. Even though Sagan was only a year older than her heroine, and may well have been the same age through at least some of the writing, the novel is not “in the moment” as much YA would be. While the novel is told in retrospect, there are only brief references to Cécile’s present. The film expands this with a flashback structure, Cécile in a monochrome Paris recalling the events of the Technicolor summer on the Riviera. It’s only at the end of the novel that Paris is mentioned. Cécile is looking back at herself from an older perspective and a certain jadedness that people detected in Sagan herself, even if they did assume it beyond her years. The film, written by Arthur Laurents, carries on this theme. Until Raymond mentions a few minutes in that Cécile is his daughter, we could take their relationship as a May-December one, not entirely impossible as there were twenty-eight years between Niven and Seberg in real life. They kiss each other on the lips and dance together, and when we do find out that he is her father, it’s also clear that she is in several ways an enabler of his love life, with a string of girlfriends of which Elsa and Anne are but the two latest. You have to wonder how faithful he was to the unnamed and now-dead woman who actually gave birth to Cécile. Laurents and Preminger more than hint at an incestuous vibe, as far as they were likely to be able to in the Hollywood of the day.

Jean Seberg was eighteen when Bonjour Tristesse was shot, in the summer and autumn of 1957, on location and in studios in England at Shepperton. Born in Iowa, she came to prominence as the lead in Saint Joan, directed by Preminger in 1957, picked out of some 18,000 hopefuls in a talent search. She clashed with Preminger – who was a known tyrant on set – and received poor reviews for her performance. However, Preminger gave her a second chance, and that was Bonjour Tristesse, although he had considered Audrey Hepburn for the role. She again had difficulties with Preminger’s attitude towards her – co-star Mylène Demongeot suggested that showing fear was the wrong thing to do to a man like that – and they never worked together again. In Seberg’s words (quoted in the commentary track), “he used me like a Kleenex and threw me away”. While it’s true that she regarded herself as being on a learning curve as an actress, it’s her performance which holds the film together, ably conveying the disjuncture between what we hear and what we see. Her stare directly into the camera as the film dissolves from present to past, from black and white to colour, for the first time, stays with you, as does the heartbreaking final shot in a mirror. The rest of the principal cast are fine, with Niven (a year before his Oscar-winning performance in Separate Tables) doing well to avoid his frequent typecasting as an stiff-upper-lip Englishman. Raymond’s being a ladies’ man was not too far removed from Niven’s offscreen life.

Otto Preminger was born in 1905 what was then Austria-Hungary, in Wischnitz (now Vyzhnytsia, Ukraine). He began his career in Vienna, directing and acting on stage and directing one feature film, before moving to the United States in 1935. Within nine years he had made one of his greatest films, Laura. By the mid 1950s, he was his own producer. He had also become a scourge of the Production Code. This had been enforced on the major studios in 1934 due to controversies over the content of much of the “Pre-Code” era, which it brought it to the end. The PCA’s first head, Joseph I. Breen, had retired in 1954, by which time the Code was beginning to seem antiquated. Many directors, not always younger ones, were clearly chafing at its restrictions on the content of their films. One of these was Preminger, who aimed a two-film broadside at the Code with the comedy The Moon is Blue (1953) and the drama The Man With the Golden Arm (1955). These attracted controversy for, respectively, such naughty words as “virgin”, “mistress” and “seduction” and a hardly enticing depiction of drug addiction, heavily hinted at if not specified as heroin. Both films were major-studio releases released without the PCA’s Seal of Approval as they refused to grant one. Preminger would clash again with the PCA on films such as Anatomy of a Murder (1959) for some explicit-for-their-time verbal details of a rape and Advise and Consent (1962), which took audiences into Hollywood’s first gay bar since the Pre-Code 1932 Clara Bow film Call Her Savage. Bonjour Tristesse is less confrontational than these; sex references were beginning to appear in Hollywood films when The Moon is Blue was less than half a decade in the past.

The 1950s was also the decade of widescreen, with CinemaScope making its bow in 1953 with The Robe. The US major studios began to make non-Scope films in widescreen (initially in a variety of ratios) and before too long the old Academy Ratio of 1.37:1 was commercially obsolete. While it’s true that many directors and cinematographers found the wider frame difficult to manage, Preminger was one who clearly took to it. His first Scope film was the Marilyn Monroe-starring western River of No Return and the majority of his films from then onwards were in Scope. (Saint Joan and Anatomy of a Murder were exceptions, both in 1.85:1.) Bonjour Tristesse is a product of the “high Scope” era, with Preminger’s frequently mobile camera often composing across the whole width of the screen in some fairly lengthy takes. The technique of distinguishing between present Paris and past Riviera by shooting in monochrome and colour respectively, was unusual but is effective, with the cinematography of British-based Frenchman Georges Périnal being a standout, with a vivid use of primary colours, blues and reds particularly, in the colour scenes. A word for Georges Auric’s music score, with a title song sung by Juliette Gréco. She appears onscreen to do so during the opening Parisian scenes, the English-language lyrics doing as much to frame the story as Cécile’s voiceover.

Bonjour Tristesse was released on 15 January 1958 in New York City. Its British release was on 27 March with a gala premiere in London at the Odeon Leicester Square. With the critical indifference on both sides of the Atlantic, the film bypassed Oscar attention. It did pick up a BAFTA nod for Best British Screenplay, but Arthur Laurents lost to Paul Dehn for Orders to Kill (1958).

Bonjour Tristesse is spine number 461 in the Indicator series, a Blu-ray release encoded for Region B only. The film was passed by the BBFC with an A certificate in 1958 but with cuts – presumably the distributor thought an A was more of a commercial proposition for this film than an X, which would have excluded under-sixteens. Nowadays, it’s a PG, uncut.

The film was shot in both black and white and colour 35mm and in CinemaScope, and the Blu-ray transfer, derived from a 4K restoration, is in the intended ratio of 2.35:1. It says “Color by Technicolor” in the credits, but by 1957 that was Eastmancolour film stock processed and dye-printed by Technicolor as the old three-strip process had been discontinued the year before. The Parisian scenes on this transfer aren’t true black and white and grey but slightly sepia, due to their being printed on colour stock, which would have been necessary due to the dissolves from black and white to colour or vice versa at each transition between present and past. At the time, colour was a selling point (you’ll often find contemporary cinema listings point out the fact that a film was in Technicolor) and Preminger and Périnal go for bold, saturated hues, particularly blues and reds. This all comes over well in this transfer, and grain is natural and filmlike.

Early CinemaScope films were shown in showcase cinemas with four-track magnetic stereo soundtrack. However, by 1958 this wasn’t always the case and Bonjour Tristesse is in mono, rcndered on this disc as LPCM 1.0. The soundtrack shows major-studio expertise at work, with dialogue, music and sound effects well rendered and balanced. English subtitles for the hard-of-hearing are available on the main feature only, and I didn’t spot any errors in them. English subtitles for the French-language Denis Westhoff interview are optional as well.

Commentary by Glenn Kenny and Farran Smith Nehme

This was newly recorded for this release, in March 2025 – which adds some resonance to American-based Kenny wishing at the start he was in Paris or the Riviera right now. They detail the film’s production and its place in the filmographies of both Preminger and Seberg especially. There was a “family” atmosphere on set, with several of the cast having some of their nearest and dearest with them. That didn’t prevent Preminger being his usual martinet self during production. Seberg wasn’t the only one to feel the brunt of this, as Georges Périnal had problems getting shots to match as the Mediterranean changes shades of blue from one set-up to the next. There is a fair amount of information about Preminger’s shooting style and his clashes with the Production Code Administration. A useful commentary if one rather on the surface of the film – rather like the film itself, in fact.

A Good Bet (4:58)

Inevitably, given that the film is sixty-seven years old, very few of the cast and crew are still with us and able to contribute to this release. (Geoffrey Horne, just about to turn ninety-two as I write this, may be the only one, but he’s not involved with this Blu-ray.) However, this short interview from 2017 with Jeremy Burnham, who passed away in 2020 at the age of eighty-nine, does give us a first-person perspective. It’s brief, because he isn’t in the film much, playing Hubert, Cécile’s boyfriend in the Parisian scenes. He met Preminger and Seberg at a party held by John Gielgud. David Niven and he had been to the same school, at different times obviously. He was an eyewitness to the relations between Preminger and Seberg during the film’s making, in particular a strong on-set argument.

Tristesse de vivre (21:52)

The other newly-recorded extra is this appreciation by Geoff Andrew. He sees Bonjour Tristesse as one of Preminger’s best films, saying that the director often asks us to observe the characters and to draw our own conclusions. Maybe that was due to his upbringing as the son of a public prosecutor in Austria, attending trials from a young age. And of course one of his greatest films is a courtroom drama endowed with considerable ambiguity, Anatomy of a Murder (1959). Although Eric Rohmer wasn’t the French critic and later director most associated with championing Bonjour Tristesse, Andrew does see a similarity with Rohmer’s work, in particular the way what characters say is often in variance with what they are really feeling. It’s entirely possible that Rohmer saw the film, and he is also one of the great exponents of taking his characters on holiday. Andrew sees echoes of the film in Preminger’s earlier films, such as Angel Face (1952), another story of young woman (played by Jean Simmons) whose angelic features are a mask for less angelic behaviour. Bonjour Tristesse is, for Andrew, a film which has the economy of many of Preminger’s earlier films but with the production values of his films of the following decade, which are often very much longer.

A Charming Little Monster (13:48)

Or rather Un charmant petit monstre, as this 2016 interview with Denis Westhoff is conducted in French, with optional English subtitles on this disc. Westhoff is introduced via caption as Françoise Sagan’s son (her only child), and a photographer, editor and founder of the Prix Françoise Sagan, a literary prize set up in 2010, six years after his mother’s death. He talks about how Sagan came to write Bonjour Tristesse, its influences largely due to her being extremely well read by that time. He regards her work as very modern for its time, in some aspects even avant-garde, but not personal at all. She was not involved in the screenplay of Bonjour Tristesse, in fact was never approached to be. However, she did visit the production several times. (While there have been many adaptations of her novels and stories, the only feature film for which she wrote the script was Landru (1963), an original which was directed by Claude Chabrol.)

Trailer (4:52)

That lengthy running time is explained by the fact that this is as much an advertorial as a trailer. In black and white Scope, Drew Pearson introduces footage of Sagan visiting the set and then interviews her, his questions and her answers filmed separately then edited together. Sagan, in heavily-accented English, comes over as awkward and the questions are all surface-level. Her future plans include “driving my life”. Then we have clips from the film itself, and from this point onwards the trailer is in colour.

Image gallery

A self-navigating gallery of ninety-three images: stills both black and white and colour, lobby cards, and several poster designs. These include those from Poland (Witaj smutku – a literal translation of the title), France, the UK and Australia, the latter two with their original A certificate and Not Suitable for Children ratings respectively.

Booklet

The booklet with this limited edition runs to forty pages. Following a cast and crew listing, first up is “Trouble in Paradise”, a new essay by Peter Cowie. This covers the background to Sagan’s novel and its film adaptation. Cowie is sometimes critical of the film, comparing it to two other films of the French New Wave or adjacent which had also been shot on location in 1957: Louis Malle’s Lift to the Scaffold (Ascenseur pour l’échafaud) and Claude Chabrol’s Le beau serge. Those two films were as naturalistic in their dialogue as their setting, but Bonjour Tristesse’s dialogue is “arch, stilted” and theatrical. However, Cowie finds the strength in the film in Jean Seberg’s persona and performance. He also mentions some disjuncture between author and screenwriter and director regarding the material. Laurents met Sagan and thought her jadedness was something of an pose in one too young to be so, something which chimed with fashion at the time. Preminger and Laurents changed the focus of the story by introducing its flashback structure and its separation of different worlds by colour and black and white. Cowie covers the production with Seberg having a hard time of it under Preminger’s direction while other cast and crew (David Niven, for example) were able to handle it better. Ultimately Cowie sees the story as not one of cynicism, but in its end self-loathing, which is something Sagan may well have identified in herself.

“Françoise Sagan, Bonjour Tristesse” is an unsigned biography of the author, derived from various sources, including her own accounts and a Guardian piece from 2014. This covers her early life and the writing of her novel, and also the near-fatal 1957 car crash (Sagan loved driving fast) which could have curtailed her literary career before the novel was even published. This also covers the differences in the film version, which is the subject of the next piece, “Filming Bonjour Tristesse” (also unsigned). The Parisian scenes were shot first and then the cast and crew headed off to the Riviera. The main location there was a villa halfway between Cannes and Toulon, owned by Hélène and Pierre Lazareff, friends of Sagan. Cosmopolitan magazine was on set, though they put a painting of Mylène Demongeot on the cover of the March 1958 issue rather than anything about Jean Seberg. Jon Whitcomb’s piece did notice that Seberg seemed ill-at-ease, something that was also noticed by another set report, by Geraldine Rae Jones for Hollywood Screen Parade. The last word is left for Jean-Luc Godard, who as mentioned before admired the film and thought of Breathless as something of a sequel to it.

Next up is a summary of contemporary reviews of Bonjour Tristesse, quoting admiring French pieces from André Bazin and François Truffaut rather than indifferent or dismissive ones from American or British critics. The booklet also contains plenty of stills.

Generally dismissed at the time outside France, Bonjour Tristesse is a film which wears its age well. It numbers amongst Otto Preminger’s best films of the 1950s, based on a novel which itself stands up, and hasn’t been lost to the fashions of the past. The film is well served by Indicator’s Blu-ray.

|