| |

"First days are always tough. You have the 100 different shots for the rest of the movie tucked away on some memory disk at the back of the brain and they keep rushing forward, out of time and place, as you make the first tentative steps on the journey. As I was told by a wise crew member on my first film, 'It's not unusual to be a day behind after the first day'." |

| |

Director Alan Parker’s Birdy Diary* |

William Wharton's extraordinary novel was deemed to be impossible to film. Told in the first person by both lead characters, the boys thoughts are delineated by the simple expedient of having one character's memories in normal type and the other's italicised. Wharton wanted black type and red type but this was deemed too costly. It's a humble but effective way of triggering who you're listening to in the mind's eye movie you create when you read a great story. But there is a great deal of internal thought and literal flights of the imagination. Stanley Kubrick once said, "If it can be thought, it can be filmed." But Birdy was still a tough ask given when it was made. With a 2019 drone or artful CGI, that impossibility simply melts way. After the fact I discover that Keith Gordon brings this up in one of the Extras (as do director Alan Parker and mediator Justin Johnson on the commentary). But Parker had 1984 technology and attempts at a flying rig failed after two takes and a crash that reduced the 'Sky-cam' operator to tears. The story of a boy obsessed with birds and flying could hardly be cinematographically earthbound. Parker improvised and it's to his and his crew's immense credit that the resulting film is compelling and beautifully realised.

Birdy is above all the story of an unlikely friendship blasted apart by war despite what the actual author may want you to believe. There's more on this delicious little matter of interpretation later. In the novel, it's World War II. Parker has updated the story and uses the far more morally muddy Vietnam War to traumatise the two friends, one whose face is patched up and the other whose trauma has sent him in to a catatonic state of helplessness after being AWOL for a month in enemy territory. The story of Alfonso ('Al') Columbato and his developing friendship with 'Birdy' is told with a dazzling structure which on paper may have puzzled the reader but editor Gerry Hambling's transitions are so clear, you feel you are being led through the story by a narrative master. There are some moments in the movie that feature intercut single shots where we go from the present, present fantasy, past memory, back to present and then the past again. You are never confused and always intrigued. I'm going to credit Hambling for this as I cannot imagine the shot order being listed in the script and I get the feeling that Parker really trusted his editor (it was their sixth film together). Hambling died at the age of 86 in 2013 so we can't ask him. If one craft in filmmaking can never be appreciated from just seeing the film, it's editing. No one except the director and the editor - those who live intimately with the rushes - know who was responsible for which creative decisions. An editor's job is to bring the director's vision to the screen. How can anyone outside the cutting room judge 'best editing' when the director may be responsible for most of the decisions? In my experience, judging 'best editing' is like pretending it's possible to reconstruct and identify the tomatoes from an exquisite Bolognese sauce. Only the cook can possibly know...

The two Philadelphia boys are brought together by the lure of making money out of homing pigeons. Both are from poor backgrounds. Al is the jock, the wrestling champ who first meets the boy we only know as 'Birdy' by picking a fight over a stolen knife. The only thing in the film that's not quite convincing is that Nicolas Cage seems a lot older than his actual twenty years. It doesn't help that shirtless he looks like a god. But let's brush past that. I suspect that there weren't that many gymnasiums in Philadelphia in the 60s though to be fair, they do train with dumbbells on screen in the slums and there are more dumbbells in the gym at the mental hospital. So, just ignore my gym observation then. Their burgeoning friendship is intercut with scenes at said mental hospital in the present day where Al visits his friend in an attempt to coax him out of his catatonic state. Early in the film, we are never told of just how both men have ended up like they have but there is enough confidence in the storytelling that blanks are filled in very easily. We hop backwards and forwards throughout the film which deepens the relationship between the two with Al consistently bemused and frustrated by Birdy's abstract obsession and with Birdy impervious to what one assumes usually goes through an eighteen year-old boy's mind.

I must single out both Matthew Modine's and Nicolas Cage's performances. They make Birdy and Al's relationship effortless and in some odd way inevitable. Any homoerotic subtext that some commentators are dying to squeeze into same sex friendships is taken care of early in the film with the bandaged Cage telling Birdy's psychiatrist "we weren't queer for each other or anything like that." I don't know where society stands today on the 'q' word so if I have to defend using it, it's in the movie. What's most striking are the changes that both men go through. Modine is not required to do a lot in the asylum although his physical representation of avian-inspired catatonia is very convincing. And it's an age away from the carefree soul and boyish charm before Vietnam put the boot camp into him. In the early friendship scenes Modine always seems to be able to see things a few inches behind Al's left shoulder, a world he's desperate to join but is forever denied entry. Membership is dependent on being able to take to the air. Cage resorted to having teeth removed because he felt it was better for the character after the injury. Respectful commitment or thespianic madness? His physical and psychological transformation is deeply jarring. That brash, fluid confidence actually pours out of him as a young man in his prime, pre-Vietnam. On the other side of the war, he's a desiccated husk, less of a man and more of a six-foot symptom of humankind's dumbest and most destructive instincts. Always the most feline of movers, Cage performs an astonishing metamorphosis. His shuffling gait puts decades on him and it's my opinion that at the tender age of twenty, I have not seen such an immensely sympathetic performance from him since. He's utterly convincing as a damaged, shell shocked, wounded returnee. And he judges the rage, the heartbreak and wonder in Al in ways that his later performances never really touched. This opinion is reinforced by the commentary, something I find simultaneously gratifying and annoying (for the frequent reason that both Slarek and I fall prey to of coming to conclusions independently before hearing the extras). The end of this film leaves me an emotional mess and of course, the film is in my top three of 'Most Satisfying End Shot' in my entire film going career. And I can't recall the other two right now...

The movie is to a large extent utterly dependent on the actors and the authenticity of their performances. Al's father, played by Sandy Baron is a fearsome creation. With Cage cowering before him after a short spell in jail over a car misdemeanour, the corrective parental smack comes out of nowhere. This coiled spring of a performance ratchets up the threat of violence after he sells Birdy and Al's car and Birdy takes him to task over it. Birdy seemingly ignores the plain fact that he is winding up a man so tightly wound in the first place, that he's toying with the pin of an organic grenade. Birdy's own father is in stark contrast a gentle, humble soul beloved by his son and as school janitor he's looked down by everyone else. He is charmingly played by George Buck. Birdy's mother, played by Dolores Sage, matches Baron's intensity, so sick is she of having her garden showered with baseballs over the years. She berates the boys at every thud of a landing homer. The actor who played the most important mutant in Total Recall, the guy with the baby sticking out of his belly, Kuato, gives one of the most unpleasant performances in the film (and I say that with some respect because it's instantly unforgettable). Marshall Bell plays Ronsky, a military clerk at the hospital who lightly spits on any paper he's preparing. It's a turn that still makes me feel nauseated. Birdy's doctor, Dr. Weiss, played by John Harkins carries more than enough authority over Al and convinces the hapless Sergeant that he may go further than letting Al try to get to Birdy. There's a hint he may be after Al too. During their scenes together in the cell, Cage and Modine convince you that despite the state Birdy has got himself in, it's Al who needs his friend back more than the other way around. The shift is subtle but it's there and either Parker's direction ensured we get this point or it's all in Cage's brutalised desolation. It's another point both men acknowledge in the commentary. I'll stop confirming these parallels now.

Peter Gabriel was a big pop star in the 80s and Parker wanted to work with him. He'd temp tracked the movie with some creative percussion from his solo albums but was told that Gabriel works at a pace that suits him not Hollywood. So Parker had his temp track cake and ate it too. Gabriel worked with existing music and remixed and reworked it for the film. And it works so well. Its slower pieces have an ethereal quality, a mirror to the bird mind but when the action demands it, the force and power of the percussion is startling. The score of Birdy is as much woven into the emotional fabric of the film as any other element and helps it soar. Modine calls Gabriel his partner in his performance, a generosity worth celebrating.

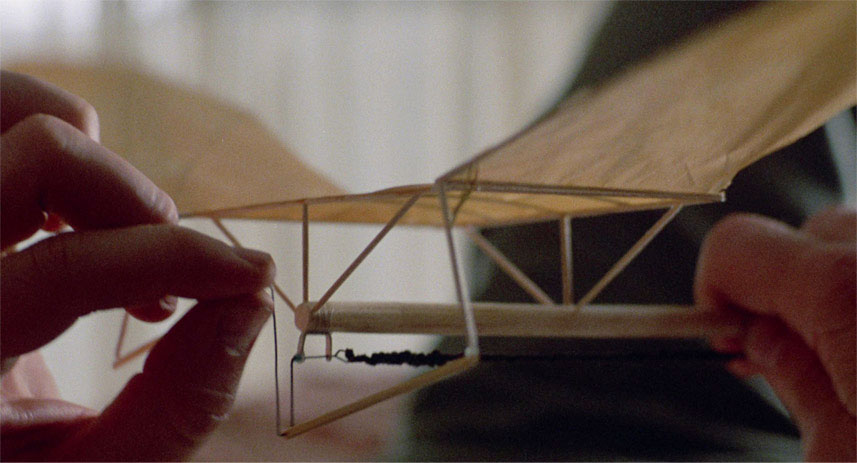

On my umpteenth viewing (this was a favourite of mine at the time of its release) I noticed how clever the screenplay was. One of the advantages of taking deep dives into movies is that the skill and intent of the filmmakers is sometimes intensified. Knowing the film so well, I registered two line deliveries of Birdy's that had a special significance that I'd not realised before now. It was the ridiculous equivalent of my once forty-eight year old self quite a while ago suddenly realising that the Bowie album Aladdin Sane was a pun. When in mortal peril as he hangs from a breaking gutter forty feet up, Modine's delivery of the line "No Al. I'm gonna fly," is actually delivered with a chuckle. This lodged in my memory and hearing again brought the film back with such vivacity. If I had to carp about anything (only if I had to)... Are we assuming that Birdy and Al cleared a smooth path in the rubbish dump? It's shot as if they are cycling through the trash and I'm not sure how believable that would be. The optical speed up of the boys is necessary so Birdy has at least some momentum to take flight but technology at the time meant that you moved one generation away from the original negative and print and so there is a variation of quality in the speeded up shot. Speeded up shots of common human actions always run the risk of risibility.

There's a similar problem in the insertion of three library shots in the climactic Vietnam scene involving Birdy. Library shots were predictably grainy in 1984 either originated on 16mm and blown up to 35mm or filmed in 35mm but were many generations from the original negative. While the crew worked hard to create a believable Vietnam (they grew the right foliage way in advance and added the odd exotic bird, namely a hornbill), the grainy nature of the inserted shots just serve as a small blip in the total immersion of the scene and its emotional power. There's also an editorial conceit that Hambling gets away with because most reviewers don't have a natural history filmmaking background. Birdy reaches out to the hornbill. The bird looks up, sees a library shot of creatures flying and this is the impetus for the hornbill to join them. There are two more importantly placed edits of the library swarms of flyers. There's only one small problem. They're not birds. I'm somewhat astonished that no one picked up on this in post-production. Was it assumed that because these creatures had wings, they were birds? Or did Parker and Hambling know and assumed no one would care? You may say the filmmakers were mad to take that risk. You could say they were batty, because the flyers certainly were - fruit bats. At the end and in the end, no one really cares. The best bit is yet to come...

Presented in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio, Birdy looks sparklingly clean and free from any of the usual suspects when it comes to film prints, things like scratches, sparkles or dust. Someone has either found a spotless print or done a lovely and subtle restoration job. Bravo, Rita Belda. The wonderful cinematography of Michael Seresin is beautifully preserved; the colours vibrant and alive in the flashbacks, sedate and muted in the clinical present. The contrast is spot on. With the four blips being an optically speeded up bike ride and three dodgy library shots (of bats), the film looks absolutely terrific.

The stereo soundtrack has a lovely full dynamic range with all dialogue crystal clear and the bass of Gabriel's percussive and dynamic score is fully rounded. Legendary dubbing mixer (called in the US, a Re-Recording Mixer) Bill Rowe has mixed an exquisite score, powerful and yet gentle, emotional and immersive as much as that over used word of Hollywood exec bullshit-speak has any shred of meaning left.

There are new and improved English subtitles for the deaf and hard-of-hearing.

New and exclusive audio commentary with Parker and the BFI's Justin Johnson

Straight off the bat, Johnson makes a small mistake that completely disarms me as you'd expect people committing to movie commentaries to be really well prepared. It's nicely glossed over. It's an easy partnership between the two men. And Parker provides some lovely detail. The truth of Cage's teeth sacrifice is probably lost in all the marketing (removed without anaesthetic, baby teeth needing to be removed anyway etc.) On top of the refinery when Birdy falls Parker tells us that Cage was really freaked out and Matthew was fearless. Asked what was done for the safety of the cast and crew, Parker replies "Prayer!" The pair brings up the Fight Club premise that both characters could be taken in the novel as one person. After author William Wharton saw the film for the first time, Parker solicited the author's opinion. Apparently he liked the film but wondered why he used two actors. When I saw that information on Alan Parker's web site, I wasn't on top of the idea that the novel could be interpreted as two sides of the same character. In a lovely revelation, at Cannes the author was with relatives who called out to him. Wharton's real name was Albert and if he couldn't be roused with cries of 'Al!', the relatives would try 'Bertie!' in a thick 't' crushing Philly accent. Al and Birdy. What novels are not ingrained with their author's psyche?

Parker celebrates the choice of his close collaborators. If you're on location for months, you want to be surrounded by friends. Makes perfect sense. Shooting nudity is discussed and there's lot of detail from Parker's essay on the making of the film both found on the director's own web site (see end of review) and reprinted in the accompanying booklet. Johnson specifically asks how the canary in the mouth of a cat was achieved and with some skill, Parker brushes over that shot but gives more information on how difficult that scene was to shoot. As I mentioned, CG and drone filming is brought up. All in all, enjoyable and informative with inevitably some overlap with the other extras in this excellent Blu-ray release.

The Abstraction of War (2019): actor Matthew Modine fondly remembers the experience of working with the cast and crew of Birdy (24' 23")

I'd never seen Modine as Modine before, just as Birdy and Private Joker (Full Metal Jacket) and the rest of his characters. Soft spoken and still with a full head of hair, he remembers the casting process in which he actually auditioned for the role of Al thinking he was unsuitable for the character of Birdy. He speaks of his spiritual side and, pausing with a caveat of "interpret that anyway you want" he credits the souls of PTSD victims rushing inside of him carrying him through the character. Okay... He takes credit for the actual perch on end of bed image with Parker allegedly announcing that "Modine's directing the movie now!" after feeling he'd got the shots he wanted. There's lovely detail about how his relationship with Cage started in preproduction and meeting Peter Gabriel at Cannes and not knowing who he was. Apparently Alan Parker (in a moment of underappreciated vulnerability) asked Modine to talk about Birdy more and not concentrate on his more famous roles for more lauded directors. His answer to that was charming and heart-warming.

Learning to Fly (2019): screenwriters Jack Behr and Sandy Kroopf reflect on the challenges of adapting an 'unfilmable' novel (13' 44")

This is an excellent and enthusiastic memoire from the two original scriptwriters. They mention that the book has everything in terms of narrative even though if it 'bounces around a lot' but if 'you peel away the feathers, it has a strong spine.' It's clear that this is a partnership that has withstood the test of time. Both clicked in their mutual passions. There's a lovely breakdown of the connection between the two distinct timelines. Also the switch in 'who's helping who?' is touched upon.

Peter Gabriel on Making the Music for 'Birdy' (2000): archival interview with the acclaimed composer (06' 42")

In an age-old (at least 15 years) technique for presenting older standard definition material in an HD frame, we shrink Mr. Gabriel's screen so the definitions match. I understand the use of clips from the film in case these extra features were standalone but it is a bit annoying to go from one extra to another and be presented with the same clips. Just a small thing. It's probably because Gabriel's company repackaged the older interview into a new frame with no knowledge of what clips came from the extra before in the list. Considering how the film affected me, I'm surprised to keep hearing how little known it was or is. Gabriel lets us in on the atmospheric creativity that gives Birdy's score such a unique sound. He tells us of his well-known love affair with the Fairlight sampler. Credits show the Gabriel sections were taken from a 2002 documentary that contradict the year 2000 listed. "I have a vewy good fwend in Wome called Nittus Pickus."

Bird Watching (2019): a personal appreciation of the work of author William Wharton by filmmaker Keith Gordon (16' 41")

Keith Gordon is a filmmaker and actor who shows great respect for fellow filmmakers and movies and it's clear he's both intelligent and sensitive, aspects of one's character that acting in Jaws 2 simply cannot accommodate. Gordon takes novelist Wharton's interior style and says it's perfect for films because getting inside someone's head is what movies do best. And there's the hat-trick! The same clips from the last two extras in fewer than 90 seconds in this one! Is this a conspiracy? Wharton got in touch after seeing Gordon's adaptation of his book A Midnight Clear. Ethan Hawke's eyes weren't blue enough apparently... I would welcome that kind of criticism! A good point is made about 'real' versus 'poetic'. He has a lot to say about filmmakers using existing music versus bespoke. And his summing up of the worth and value of Birdy is something this writer wholeheartedly agrees with.

Original theatrical trailer (02' 43")

Oh God! The first shot... guess what it is? Yup, the same shot that's at the start of the previous three extras! It's starting to feel designed to break my will! This is a solid trailer with no captions or voice over just dialogue and two or three of Gabriel's cues. I'm not sure how successful it turned out to be. No part of the film is withheld and each time period is represented, the horrors of the Vietnam War included. This would have intrigued me. Obviously a lot of people weren't.

Image galleries: promotional and publicity material, and a selection of rare items from Matthew Modine's personal collection

The official bunch include 14 colour publicity pictures, 1 B&W front of house still, a poster bedecked with favourable quotes then back to 3 B&W FOH stills, then the German poster and the US Poster.

From Modine...

7 x colour shots from the Cannes Film Festival (including ID and invitations), 2 x 2 photo booth pictures from the 'getting to know Nic Cage' pre-production, 1 B&W shooting shot in Philadelphia, TriStar's 10 page 'For your consideration' booklet, pressbook cast and crew sheet and 5 x promotional cast and crew pictures (the first with the supporting wire visible for Birdy's rubbish dump flight) finished by two colour shots of Modine on the ground and with wings in the air!

No Hard Feelings (1976): Parker's early film, which follows a troubled young man in wartime London (54' 41")

Well, that was cheerful! Joe Gladwin, soon to be a comedy staple as the comic Northerner in the long running BBC sit-com Last of the Summer Wine, plays the widowed grandfather of a family suffering under the Blitz in World War II. Screaming children, the overhead threat of being bombed and the sheer discomfort everyone is feeling effectively dispenses with the Blitz spirit that some Brexit supporters seem to think typifies their struggle to leave the EU. If it was grim up north, it's positively unbearable in the Capital. When the bombs start dropping we realise that Gladwin's son played effectively by Anthony Allen has shellshock from witnessing his mother's death and that his sister, weighed down by infants, is well passed her tolerance date and wants out. The sister, played by Kate Williams, also had a career in UK sit-coms, notably On The Buses and Love Thy Neighbour. If you know what 'woke' means in 2019, never ever look those shows up on You Tube. Allen is romancing Mary Larkin and she comes to symbolise the slight tether that's holding him from total neurotic collapse. Things do not go smoothly. There's a casual telling of a rape that would not be allowed in today's climate and two instances of a very familiar piece of music that became hugely famous but for its inclusion in a film made six years later. Parker must have been annoyed at that. It was originally written for another film by Stanley Myers and skipping Parker's use, it became famous for its rendition by classical guitarist, John Williams in 1978's The Deer Hunter. It is of course Cavatina.

One small typographic oddity; at the end of the film is the usual Latin date for copyright purposes. Curiously it reads MCMLXX1V instead of XXIV.

Limited edition exclusive 48-page booklet with a new essay by Frank Collins, an extensive account of the making of the film by Alan Parker, an overview of critical responses, Jeff Billington on No Hard Feelings, and film credits

Frank Collins' 'In A Dream, I'm Trying To Decide What I Am' gives terrific background on novelist Wharton (I really didn't realise just how autobiographical the novel was). The details are fascinating. There's a photo credit on page 13 that reads 'Cage and Karen Young'. As far as the text is concerned, Young plays the nurse only in scenes with Cage in full facial bandage mode. This girl is the one Cage makes out with at the start and they are interrupted. Her character name isn't mentioned so I can't credit her. Parker's own 'Birdy: The Making of the Film, Egg by Egg' is available on Parker's own web site so I'd read that for research. And it's a terrific read and full of hugely useful filmmaking anecdotes and tips. There's a lot of crossover as there will inevitably be with the commentary but it's still a cracking and entertaining read. Critical Response features a very common complaint from the Monthly Film Bulletin's Richard Combs. Knowing Parker's commercials background, he magically finds the director incapable of anything but bite size effectiveness until he adds that the structure of Birdy suited having this sort of aesthetic. The Janet Maslin extract from the New York Times' review gives time to the supporting cast and the animals. Roger Ebert loved the film and said it was "impossible to put this movie out of my mind." Lovely.

'No Sugar' by Jeff Billington looks at Parker's first film made in 1972 and bought by the BBC, No Hard Feelings. As I mentioned, it's not exactly uplifting material. Billington gives historical context, background on the actors and its primary rejection by Granada to be eventually taken up by the BBC.

One of my favourite 80s movies, Birdy works so well for me because of the performances. How much of the credit for these we lay at Alan Parker's feet can never been known but I suspect a fair bit. It's sensitively directed, exquisitely edited and Gabriel's extremely unusual score makes a film that stands out, stand out even more. Hugely recommended.

|