| |

"To me it can apply to any sphere of business or the arts where man's natural liberty or freedom to express himself can be squelched by unworthy, incompetent, tyrannical leaders or bosses who don't deserve their powers." |

| |

Robert Aldrich on The Big Knife, as interviewed by George Addison in 1962 |

Robert Aldrich's relentlessly caustic adaptation of the Clifford Odets play The Big Knife finds Jack Palance playing Charlie Castle, a movie star dealing with a studio boss (Rod Steiger) insistent that he sign a new contract just as the tumultuous relationship with his wife Marion (Ida Lupino) seems to depend on him doing the opposite. The wrinkle that emerges involves blackmail, Shelley Winters as a formerly contracted actress now more or less a prostitute, and a possible allegory for McCarthyism. The ensemble of actors wallow in loud misery as an often pervasive sense of unhappiness becomes inescapable.

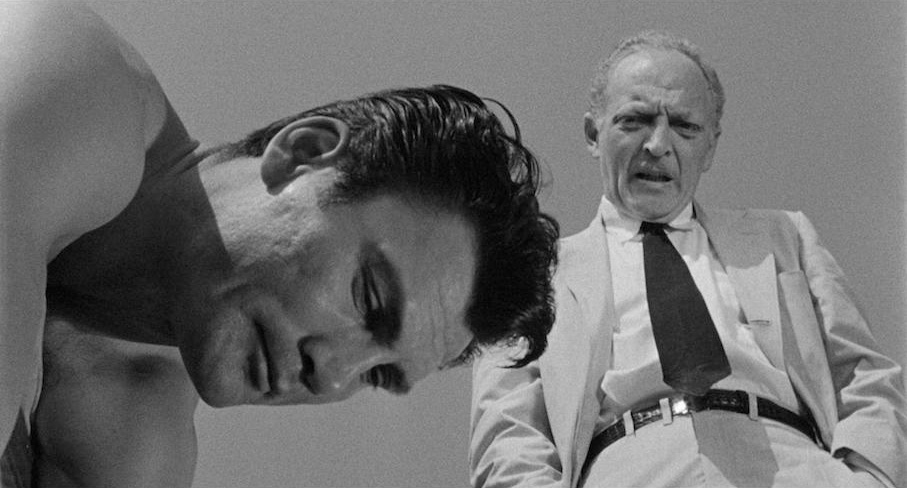

The film opens with a terrific Saul Bass title sequence, punched up by its jazz score. It shows Palance looking downward, surrounded by darkness, and grabbing the hair on top of his head. Bass crisscrosses the frame with white lines to show the anguished Palance literally cracking up before disappearing entirely as the screen goes white and Aldrich's credit appears. A voiceover (by Richard Boone) then places us in Bel Air as Palance's Castle and one of his assistants spar in boxing. The action soon moves inside, to the room which will become the film's primary setting – a den that feels more like a fancy cage than a haven of domesticity.

This sense of claustrophobia both extends to the viewer and informs how we see the protagonist. Castle is trapped in a number of ways here. There are the obvious limitations that would come with signing the new contract studio head Stanley Hoff (a bleached blonde Steiger) aggressively pushes on him, as well as the blackmail Hoff holds over Castle should he refuse. Castle is also somewhat trapped in a marriage to a woman he seems to love on some level yet to whom he has not remained faithful. He's essentially beholden to all of these people – not just to Hoff and Marion but also Winters' Dixie and Buddy, his publicist who took the rap for a hit and run and was promptly thanked by Castle sleeping with his wife (Jean Hagen).

Palance may not have seemed liked the most obvious choice to play Castle (and Aldrich apparently had first wanted Burt Lancaster), in part because he wasn't really a movie star himself so having him portray one as well as carry the film by appearing in virtually every scene was risky. Indeed, the production did not do well commercially (though director and actor quickly re-teamed for the brilliant war picture Attack!). But if you mostly know of Palance through his Oscar-nominated supporting turns in Shane and Sudden Fear or his late-career comeback with City Slickers then the performance here should be revelatory. What's particularly affecting is the vulnerability the actor manages to convey. This character is a privileged philanderer who's committed an awful crime that saw someone else be punished, yet the viewer still can connect and sympathize with him. That doesn't happen without a performance of great dimension and depth.

The thing with Charlie Castle, too, is that he's not a terribly bright guy. Comments about a painting which hangs prominently in his house indicate a general lack of sophistication or sense of curiosity. John Garfield was great at playing these kind of rough, evolving but not yet evolved characters. Indeed, Garfield originated the role on Broadway in 1949, just one of several times he appeared in Odets' work on stage, and is frequently identified as the role model for Charlie Castle. His death three years later is often linked to the stress that came from the intense scrutiny of the Hollywood blacklist and HUAC, the congressional House Committee on Un-American Activities. It's further assumed that Clifford Odets intended The Big Knife to be an allegory for McCarthyism, and one can put those puzzle pieces together as necessary if desired. Certainly the dozen or so (rather acrimonious) years of working in Hollywood must have also informed the play a great deal.

To be sure, it paints a relentlessly nasty portrait of Tinseltown. From Steiger's spewing turn as a Hollywood studio head who comes off like a mob boss to Smiley, the fixer character Wendell Corey menacingly underplays, there's a clear connection between the movie industry and a feeling of being either above or ahead of the law. Films like Wilder's Sunset Blvd. and Ray's In a Lonely Place had already explored the ruthless, cynical side of the town but The Big Knife peels back a somewhat seedier layer. Much of what occurs here is clearly criminal on its face yet manipulated into a sanitized form of acceptability. Steiger, just approaching 30 during filming but clearly intended to be much older, is a monster of power and intimidation who's controlled as much by his paranoia as his ambitions. What he's running is much closer to an organized crime ring than the dream factories movie fans like to envision for the studio system.

Director Robert Aldrich actually made The Big Knife independent from those studios and seemed to think highly of his film version, adapted for the screen by James Poe. It was shot in just 16 days in 1955, released the same year as his quintessential noir Kiss Me Deadly, and the first outing from Aldrich's production company. It went on to win the Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival. Viewers can see themes and characteristics familiar from other Aldrich films in The Big Knife. The struggle for individuality and survival pops up frequently across his filmography. An insistence on at least attempting to eschew the system also emerges here. The violence often attached to Aldrich's work is less overt but conflict clearly remains surface-level and beyond for much of the film. His keen fondness for the anti-hero hangs heavily over the picture.

The movie also often gets tagged with the film noir label quite a bit and that may not be accurate or helpful. Emotionally and thematically it might have noir elements but it certainly doesn't share the aesthetic nor does it contain the classic tropes that many look for in the dark cinema. Those going into The Big Knife with noir on the mind might very well be disappointed by the loud, bombastic acting of Steiger and extremely dialogue-driven long takes Aldrich uses. It's very much a fifties movie – a melodrama – that embraces its theatricality while bravely turning the screw of darkness tighter and tighter until delivering an ending that's utterly bleak.

Arrow Academy in the US and UK bring The Big Knife to region-free Blu-ray.

It's been reported elsewhere that Arrow's version of the film differs from an earlier DVD released by MGM in that it is missing just over a minute of footage and dialogue previously present on that edition. The included booklet indicates that the source was an original 35mm fine grain positive, making for an odd inconsistency. As of this writing, word is that the Arrow team is still investigating the issue.

The film here is presented in widescreen, in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio. It had previously been offered on DVD by MGM in Academy ratio (1.33:1). (A special thanks is given in the Arrow booklet to Robert Furmanek, a noted film historian who's often consulted on aspect ratios and presumably offered evidence of 1.85:1 as the original and/or intended framing.) Since Aldrich's previous effort Kiss Me Deadly has also been issued in widescreen (1.66:1 on Blu-ray from the Criterion Collection), this at least seems like a somewhat consistent choice.

Arrow, under James White's supervision, went to the effort to restore the film in 2K for this release. Showing virtually no damage, the picture looks cleaned up and clear. Contrast appears excellent. Grain is almost constantly present in the image, perhaps more than what we would see on some films, but the effect is never oppressive. There is some mild flickering on occasion. The overall impression, though, is a positive one and the film looks very good on the whole.

The offered English language audio emerges through a two-channel LPCM mono track. It allows dialogue and the Frank Devol score to sound crisp and absent any obvious damage or issues. The balance is subtly effective, as Devol inserts various musical elements, from jazz to a military style drum piece sneaking out of the dialogue back and forth of Palance and Steiger. English language subtitles for the hearing impaired are optional.

An audio commentary from New York-based critics Glenn Kenny and Nick Pinkerton finds the pair chatting about a range of topics. They find time to discuss John Garfield's professional pairings with Clifford Odets as well as repeated talk on director Robert Aldrich, including some notes from various interviews he gave. They also quickly dismiss the idea of the film as a noir, making one wonder who exactly ever attempted that classification in the first place. The two men offer nary a hint of dead air. Their commentary is generally focused, insightful and easy to listen to without seeming scholarly or academic.

The 1977 documentary short Bass on Titles (33:46) finds the legendary Saul Bass talking over several of his famous movie title sequences, including Seconds and West Side Story, explaining his process and ideas. This is a great, highly interesting extra and a must for fans of Bass. The scenes from the films, and the short on the whole, are unrestored and presented in a native 1.33:1 aspect ratio.

A neat television promo (4:59), announced as the first time cameras were allowed to enter a movie soundstage, finds the film's actors talking a little about the movie from the set. Jack Palance plays host as film clips are mixed alongside other cast members speaking directly to the camera – breaking the fourth wall in a sense – about their roles. The really striking thing is to see the actors so jovial as they promote such an unhappy film.

A theatrical trailer (2:28) uses the 1.33:1 aspect ratio and promises the "Hottest Hunk of Film Hollywood Ever Shot" in hyperbole typical of the era.

A forty-page booklet has been included inside the case for the initial pressing and, in addition to stills and credits, features two primary pieces of writing. The first, commissioned for this release, is an essay on the film by Nathalie Morris. It traces some of the film's history and development alongside sprinkled bits of analysis. The piece runs slightly over four pages of text. Much longer, approaching eleven pages of text, is a Clifford Odets article written by Gerald Peary in 1986 for Sight & Sound. Odets' career, particularly his relationship with the movies, is explored with some depth as Peary makes the case that the famed writer's frustrating time in Hollywood was a selling out of his talents. The article also dismisses Aldrich's The Big Knife as "foggy and ill-motivated, probably because it was too loyal to the original script" and labels the play itself as being "as muddled and contradictory as Odets' own vacillating opinions of Hollywood."

Like many of Robert Aldrich films, The Big Knife has really grown on me over the years. It's clearly not a film noir, and once I made peace with that fact it was easier to appreciate Clifford Odets' sharp dialogue and the remarkable acting we see in the picture. It's more of a melodrama, and the relationship between Palance's Charlie Castle and his wife Marion, played by Ida Lupino, is really what holds the movie together. For all of Rod Steiger's scenery-chewing and Wendell Corey's comparatively quiet menace, it's a scene early on that Palance and Lupino share, discussing their future as it relates to the contract, that particularly resonates. It's tender in unexpected ways, as is a later exchange between the two, and it also makes the ending fate all the more damaging. The Arrow Academy edition, despite what seems to be an unintentional omission of a minute or so of dialogue, gives the film the kind of first-class treatment that is as unexpected as it is welcomed.

|