| |

“The reason I saw Moses Wine as a vehicle for expression was that he shows my growth away from that seventies cynicism. I still feel it, though. The seventies have been a much more insular, much more gracelessly selfish time, much less noble. It’s funny. I’ve had the time of my most incredible personal success in the seventies and I’m still hard pressed to remember what year it is. I can remember the sixties month by month.” |

| |

Richard Dreyfuss, Rolling Stone Interview 1978* |

Moses Wine is a name that tends to stick with you. He’s an ex-radical activist, a divorcée and a man who wears his heart if not on his sleeve, then certainly tucked in his plaster cast, a fixture that accompanies him throughout the film protecting a real wrist break. In a touching scene in The Big Fix, we see his own history spill out of a screen while he’s investigating a case. The canard about the 1960s is that if you can remember the decade, you were never there. I have vague memories of Thunderbirds, both on TV and the toys on my bedroom carpet, a Scaletrix set, the Beatles, flying ants and an accident with no permanent physical effects but waves of revulsion on recall. I fell (or was pushed) into a giant bush of stinging nettles. I felt like I was stung everywhere. But the problem was I couldn’t get out of the bush without opening myself up to the same experience pulling myself up. To Moses, the barbs of that passionate period were ultimately understanding that despite the change and the will for change, nothing really dented the forces Moses and his ilk were aligned against. God, how relevant is that feeling today? There are few emotions available to us more powerful than belonging to a justified cause, and those emotions are profound. Moses gets very moved but there is a small feeling that he’s mourning a failure and not nostalgically having a wallow. The Big Fix is in some respects a nod to the human spirit and a yearn to return to a period where love and peace actually became tangible goals after significant consciousness raising.

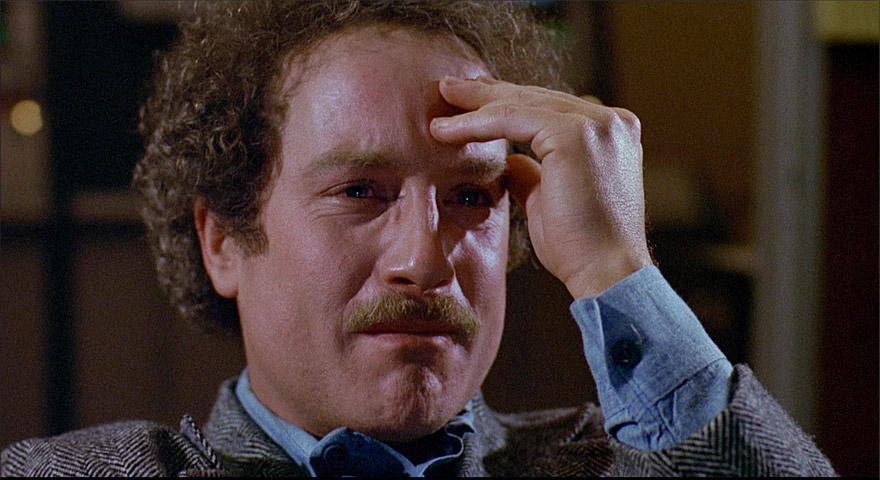

Moses Wine is introduced to us counting chickens. I’m pretty sure those chickens were hatched. A cop approaches him, suspicious. Moses introduces himself and shows the cop the gun he has in the glove compartment of his VW Beetle. A crayon is inserted in the barrel. The cop says “That’s no way to treat a weapon,” to which Moses replies “I got kids.” This is a charming introduction to our main character. Richard Dreyfuss had no physical qualities of a conventional leading man although he’s a lot leaner than in his Matt Hooper role. Aside from surviving an attack from Bruce, the polyurethane great white by escaping the anti-shark cage before he can be munched upon like so much biltong, the fate of the novel’s character, his star credentials were almost totally based on his innate charm and charisma as a performer. Dreyfuss is physically dwarfed by many of his co-actors but his Dreyfussness is more than enough for us to go along with him on this unusual but hugely entertaining ride. His character is strongly established by his interactions with his two children, his lonely home life playing Clue by himself and his frustrations with his ex-wife’s new beau.

Here I must segue into a personal anecdote to give some meaning and weight to The Big Fix’s parody of an aspect of US culture in the late 70s and early 80s that most people probably will never have heard of. In the film, Randy Esterhaus is a ‘Best’ trainer whose smarmy announcements paint himself as a self-satisfied, enlightened soul offering his nuggets of wisdom when none is asked for. As each one of these barbed gems lands, Moses counts down. “That’s one…” You wonder how far that’s going to go before some sort of resolution. Cringeworthy to a fault, Randy is played by Ron Rifkin - the district attorney held outside a high storey window by his legs in L.A. Confidential – he’s satirising an enlightenment programme known as ‘est’. Director Phil Kaufman was also parodying the ‘est’ technique of breaking you down and forming a different person in his superb remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers. First of all you pay $400. In 1982 when I did the training in San Francisco, that was all the money I had and is now worth two and a half times that. You then commit to spending up to 16 hours a day over two weekends in a hotel ballroom. Bathroom breaks were discouraged and you had one meal break. The first weekend was almost all sit and listen to two ‘trainers’ who systematically broke you down psychologically in an effort to expose the ‘self’ and not the masks and identity we all assume every day. On the second weekend, you learn about how the mind works its magic and through a series of consecutive steps of self-realisation, you reach the climax of this glorious two weekends of psychological participatory theatre and you either ‘get it’ or you don’t. The aim of the training, apart from making money, was to (in the training’s marketing copy…) "transform one's ability to experience living so that the situations one had been trying to change or had been putting up with clear up just in the process of life itself.” If you want to know the details of the fascinating process, have a read of this:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erhard_Seminars_Training.

Before the start of the training, you fill out a form and one of the questions was “What do you want to accomplish from the training?” and I put “I want a job on a film set.” Well, I may not have ‘got it’ the way many others did but I did get a job on a film set a few days after the training with almost no money left for the rest of my American adventure. It was an astonishing time and The Big Fix’s Randy nails that overbearing arrogance of the trainers that wore you down. Personal segue, over.

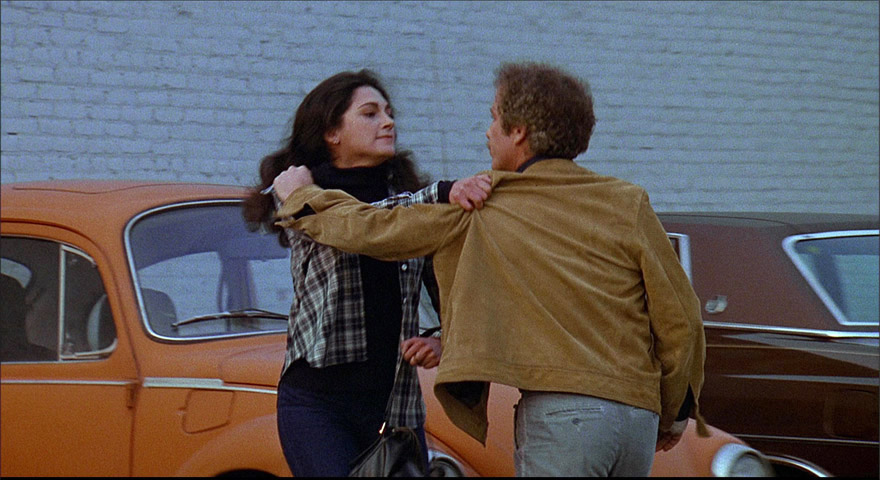

Moses is hired by a political campaign manager via Lila Shea, an ex-girlfriend of Moses’ to find out if one of the infamous ‘Californian Four’ - now in hiding - had anything to do with flyers linking a known felon with the candidate. The breezy investigation, during which Moses and Lila reignite their enthusiasm for each other, ends abruptly. The stakes are raised and Moses is forced to dig deeper to get to the truth. The plot is fairly labyrinthine with assassins, sold out ex-activists and warring families but Moses manages to tie things up. Dreyfuss is supported by a cast, all of whom went on to bigger roles in more famous movies. Sam Sebastian is the campaign manager played by a young John Lithgow. While I think his Dr. Emilio Lizardo was a performance of no small genius in Buckaroo Banzai, seeing him play a down to earth ‘normal’ person is, in its own way, quite shocking. I had a big crush on Susan Anspach who plays Lila when I first saw The Big Fix, having loved her performance in Five Easy Pieces with Jack Nicholson showing how good an actor he actually was. Bonny Bedelia plays Moses’ ex-wife and despite a steady working career over 63 years, she’s probably always recognised for one role, John McClane’s estranged wife Holly in the first and subsequent Die Hard movies.

Eagle eyed viewers will spot the man everyone seems to be looking for, Howard Eppis. Played by a pre-Amadeus F. Murray Abraham, it’s a lighter and more touching character than most roles he subsequently was cast in. My favourite moment of the film is just after he asks Dreyfuss resignedly (a fellow activist though Howard doesn’t know this) “How much do you want?” Dreyfuss smiles and bonds the two men with the throwaway line “Not a penny, Howard.” I just loved that connection. Three actors with relatively small roles still shine. There’s the garrulous swimming pool maintenance guy. Blink and you’ll miss Mandy Patinkin in his first cinema role, nine years before he became famous for saying “My name is Inigo Montoya. You killed my father. Prepare to die,” in The Princess Bride. I’d like to point out Frank Doubleday as the second assassin. Talk about being typecast. His distinctive look is never given a close up but he will be forever championed as the nihilist gunman who quietly shoots a girl in the chest asking for vanilla twist in Assault on Precinct 13. Finally there is Larry Bishop as Wilson, an investigator who in one scene made a huge impression simply from his nasal delivery of a question oft-asked, “Where is Howard Eppis?”

While director Jeremy Paul Kagan isn’t as comfortable with what may loosely be called ‘action scenes’, something mentioned on the commentary, his work with the actors is top notch and while the narrative gets a little twisty-turny in Act II, it’s not long before Dreyfuss has a handle on who’s doing what to whom, why and how he can actually prevent part of the L.A. freeway from blowing up. And while Dreyfuss tailors different answers about how he broke his wrist fictionally to appeal to every different person who asks, we do finally find out what really happened in an almost too cute coda. The Big Fix is undemanding Raymond Chandler-lite, rooted in the seedier areas of Los Angeles. The score by Bill Conti coming off his iconic score for Rocky is Lalo Schiffrinesque recalling the jazzed funk of the later Starsky and Hutch seasons. The film features a fine emerging cast of great talent and has a light comedic touch which gives way when suddenly things get serious. The attitudes are of the late seventies and there are bound to be a few youngsters today who may respond badly to a few scenes as they are somewhat out of touch with our current social thinking. But for a lightly played detective yarn, The Big Fix delivers nicely.

This 1.85:1 aspect ratio late seventies movie looks in pretty good condition though there is a smattering of negative sparkle and dust spots if you are really concentrating hard. The film grain is evident but undistracting. Frank Stanley’s cinematography in sunlit Los Angeles and the softer lit interiors is naturalistically unshowy with good colour reproduction and contrast levels consistent overall.

The original mono soundtrack is in good shape (though the trailer’s mix could do with some work, way too much traffic background noise but that’s always the issue with no ADR, only sync tracks recorded at the location). The dialogue is mostly clean and the mix has nothing disruptive of any nature to the clarity of the sound.

There are new and improved subtitles for the deaf and hard-of-hearing.

Audio commentary with Little White Lies editor David Jenkins (2021)

The first thing you become aware of is Jenkins’ voice, a low register which seems to quietly whisper in respect of the film playing out in front of him (it turns out he has a cold). It’s very sweet. Jenkins has a wealth of background detail on the actors, the screenplay’s machinations and provides the root system of the political stance taken by the film. Both right and left get blasted as 60’s idealism slowly gives way to 70’s indifference, personal ambition and materialism. Whether Jenkins had heard of ‘est’ or not (see main review), he brushes aside the ‘Best’ wisdom-spouting partner of Dreyfuss’ ex-wife as simply New Age jargon. He also has lots of background on Los Angeles clubs at the time. His ongoing appreciation of Dreyfuss’ performance is also a nice touch. He takes Dreyfuss’ journey with us and rarely just lets the movie play when underlining certain points of interest. After the event that ratchets up the drama, Jenkins notes that Dreyfuss and John Lithgow are “…on the World Turkey”, a slip of the tongue indicating the Wild Turkey brand of bourbon which for some silly reason tickled me imagining a multi-talented turkey on some world tour. Larry Bishop’s role is underlined and it seems that Jenkins has the same fascination with this actor and character as I have. While having no enthusiasm for director Kagan’s handling of action scenes, Jenkins talks about Dreyfuss as an actor giving a very detailed run down on his career with a big nod to his role as a pornographer in Inserts. And despite his fondness for the film, he’s certainly not shy in delivering a few critical remarks. Finally, he reveals that he had been speaking through a cold and hopes the folks at Indicator edited out the evidence. This is a solid commentary with a wealth of information about the film.

The Big Self (2021): director Jeremy Paul Kagan discusses his early career as a filmmaker (22’ 36”)

Without doubt, one of my favourite extras from the past few years. The Big Fix was made in 1978 so there’s always that wonderful surprise that the creatives are (a) still alive and (b) cogent and politically aware. Using a muppet avatar to top and tail his Zoom recording, Jeremy Paul Kagan is a charming revelation. Framed in front of a still of him and Dreyfuss working on the film, the bald and bearded Kagan is a non-stop provider of passion, commitment and playful proselytisation. If that last word is as rare as I think it might be, let me admit that I was introduced to it via a Playboy interview with Roy Scheider in 1980 who was actually talking about ‘est’ which is one coincidence and being Dreyfuss’ co-star in Jaws, is another. It means to advocate or promote a belief system in order to convert others. At 16’ 55” there’s a black frame (I’m an editor, I can’t help it) a consequence of editing a Zoom recording perhaps. I just got utterly swept up in Kagan’s passion. Great stuff.

The Crime in Mind (2021): screenwriter Roger L Simon recalls the origins of The Big Fix and the process of translating his novel to the big screen (07’ 41”)

This is also a charming extra feature with the writer of the original novel and screenplay. Can I ask a small favour of those crews covering these extras? Can we have cutaways of detail on the participants’ bookshelves? The titles are always tantalisingly out of easy view. The best wallpapers in the world are book spines and the best gateway to a person’s character is which ones you can read at a 90° angle. Simon seems to fondly recall the days of his late seventies creativity and his involvement with the film.

Archival TV Interview with Richard Dreyfuss (1978): the actor and producer in conversation with Bobbie Wygant (5’ 16”)

Dreyfuss talks about identifying with Moses from the novel. On his own without his writer, producer and director, he comes across as a trifle reserved at first but loosens up a lot later. To my surprise, he states that Roy Neary in Close Encounters was his hardest role (no self-awareness apparently). He talks about the ‘Oscar effect’, and blasts the myths that have grown up around the awards. As they wind up, Bobbie Wygant (dare I say a female?) says to Dreyfuss “I love you. Can I take you home?” which gets a spontaneous belly laugh from the star.

Archival TV Interview with Jeremy Paul Kagan, Roger L Simon and Carl Borack (1978): the director, writer and producer chat with Wygant (6’ 49”)

Carl Borack was a close friend of Dreyfuss’ from schooldays whose relationship weathered the storm of production. Lovely to see the younger version of author Stine who makes the rather wonderful error of criticising a scene in the film (on a press junket)! Director Kagan takes him to task and in that moment with the three men interacting loudly, you got the impression that making this film much have been a great deal of fun. Kagan’s character is as passionate and funny as he is as an older version of himself. This is a charming extra that I would point to if anyone asked me what ‘chemistry’ looked like on camera.

Original theatrical trailer (3’ 01”)

No risks taken with this trailer. Exposition heavy and in the 4:3 ratio for TV one assumes, it jackdaws from many scenes to present a real guy in a “…desperate and violent world.” The ad campaign is hung on the hook of Dreyfuss’ likeability and in squeezing in some police action and a gunshot, the trailer tries to snare the action crowd.

TV spot (30”)

“He’s a lover, he’s a kidder, he’s a father…” Yikes, a bit too much syrup for my taste but the ad was probably audience tested to death. As David Mamet observed, if market research worked with movies, there’d be no flops.

Radio spots (1’ 35”)

With Bill Conti’s theme clip-clopping in the background, critics’ words re-enacted by actors go so far over the top, they need oxygen on the way up. The second of two spots is a shortened version of the first. I find the absolute adoration of the film and overboard appreciation of Dreyfuss a little heavy-handed though was quite amused by the phrase “endearingly aggressive self” to describe the lead actor.

Image galleries: promotional and publicity material

We have 19 extremely high contrast black and white stills, 13 colour stills, 3 Front of House black and white stills, a review as poster and two poster designs.

Limited edition exclusive 32-page booklet with a new essay by Andrew Nette, an introduction by Richard Dreyfuss, archival interviews with Jeremy Paul Kagan and costume designer Edith Head, an overview of critical responses, and film credits

Andrew Nette’s The Big Fix, The End of the 1960s and Cinema’s new Private Eyes casts an (ahem) eye on how changing decades demand more of the private investigator and how in times gone by, hope also went by as the 60s came to an end. His final paragraph summing up is alarmingly similar to my review’s first paragraph but again, I always read the booklet last, no cribbing, only coincidence. Richard Dreyfuss’ own Introduction to the film reminds me that Dreyfuss practiced what he preached in supporting the education of civic responsibility in schools and encouraging young people to vote. His left-wing idealism, chipped and worn by the years is still very much in his soul but our reach to be better human beings has not fared well since the fabled 1960s. In fact, right now we may be living through our lowest and darkest era politically. Apathy and cynicism are opening the doors to a ‘new’ politics and it stinks all the way down. Engage, people! Reach further!

Edith Head: Blue Jeans and Blouses is an overview of this renowned costume designer and if any more evidence is needed that she was the inspiration of The Incredibles’ Edna Mode, then take a look at the first photograph. In the article she bemoans the shift from glamour to realism. In the early Hollywood days, actresses playing housewives of working class men manage to suddenly sport a designer gown or bespoke evening dress worth two months’ salary. Not anymore. Head dominated the Hollywood costume design department being nominated 35 times for an Oscar™ and winning 8 times. An Interview with Jeremy Paul Kagan six years after the movie opened fills in some personal information and the rise of his career from visiting the set of Stanley Kramer’s Ship of Fools to awards at the American Film Institute to television. A TV Movie got noticed and his film career kicked off. Critical Response highlights a passage from the Monthly Film Bulletin and Tom Milne’s extremely intellectual reading of the film. I stopped short at the use of the word ‘adumbrates’** and wondered what atmosphere can someone grow up in and not only learn that word but find a way to use it. It wasn’t a rave review. I am delighted by the fact that almost all the older releases graced with a booklet with critical responses of the time feature reviews that had no benefit of hindsight and were usually lukewarm or negative. Time seems to gift films worthy of a second chance. That said Gordon Gow’s Films and Filming review and Roger Ebert’s are pretty positive.

The Big Fix is an undemanding, italicised take on the private detective genre taking in the fall out and disillusion of the hope of the 1960s. It’s buoyantly entertaining with a likeable lead and a strong supporting cast (and a real cast). Its fervently left wing protagonist makes a welcome change and director Kagan’s way with actors is to be loudly applauded. Warmly recommended.

https://www.rollingstone.com/movies/movie-news/richard-dreyfuss-the-rolling-stone-interview-46406/

Adumbrate: verb, formal (you think?)

1 represent in outline: Hobhouse had already adumbrated the idea of a welfare state. • indicate faintly: the walls were only adumbrated by the meagre light.

2 foreshadow (a future event): tenors solemnly adumbrate the fate of the convicted sinner.

3 overshadow: her happy reminiscences were adumbrated by consciousness of something else.

|