|

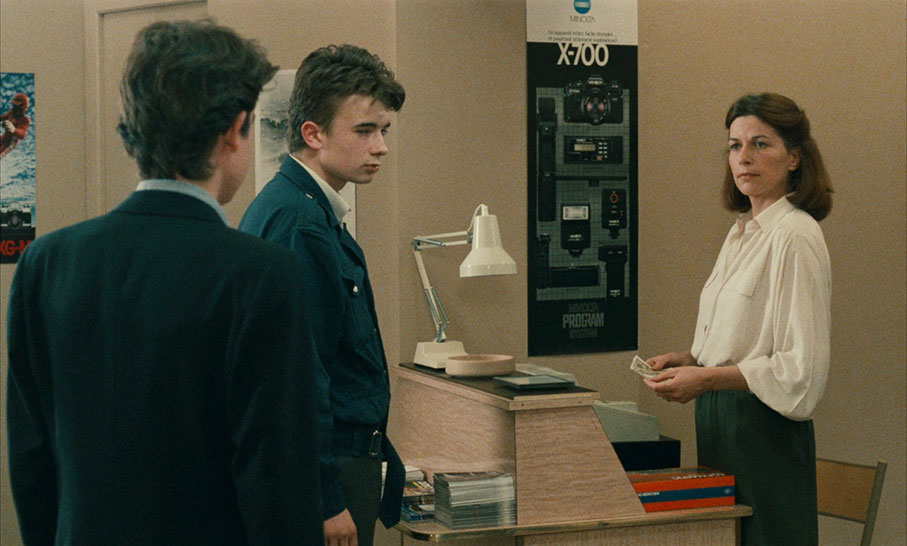

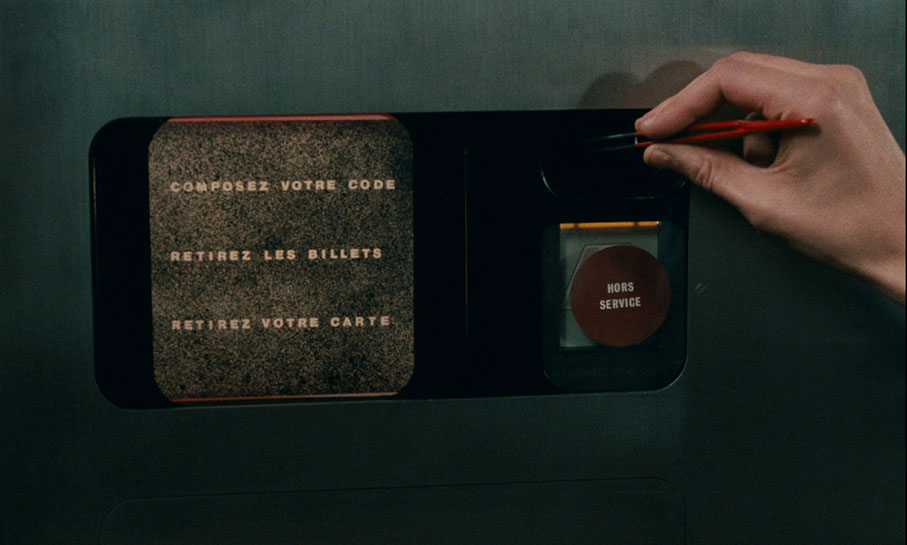

When asking for his monthly allowance, Norbert (Marc Ernest Fourneau) asks his father for more, to clear a debt to a schoolmate. When his father declines, Norbert tries to pawn his watch to a friend, who gives him a forged 500-franc note in return. They use the note to buy a picture frame at a photo shop, and the owners intentionally pass the note and two others to Yvon (Christian Patey) who is there to fix the heating. Yvon unknowingly uses the notes to pay for a cafe meal but they are declined and he is arrested...

Released in 1983, L'argent was Robert Bresson's thirteenth feature film, when he was eighty-one (there is some debate as to his year of birth, though it was most likely 1901). It wasn't intended to be his final film, though that's what it turned out to be. If only in hindsight, you can't help seeing it as a final testament, as a distillation and culmination of his themes and techniques, and you wonder how much further he might have gone. It's a spare, uncompromising film that has to be taken on its own terms or not at all. By this time in his career, his films – with their emphasis on the workings of fate and human suffering – were decidedly bleak. They could hardly be bleaker than his previous film, The Devil Probably (Le diable probablement, 1977), which had been restricted to the over-eighteens in France for fear it might inspire suicides.

Many of Bresson's films were based on pre-existing sources. He filmed novels by Georges Bernanos twice (Diary of a Country Priest and Mouchette). He adapted stories by Dostoyevsky in consecutive films, namely Une femme douce and Four Nights of a Dreamer, the latter from the novella "White Nights", previously filmed by Luchino Visconti in 1957 under that title's Italian translation (Le notte bianche). Both of those films relocated the nineteenth-century Russian originals to contemporary France and L'argent did the same with a novella by Tolstoy, "The False Note", or rather the first half of it. The film is a something of an ensemble piece at first, tracing the progress of the false bank note through a small group of characters. However, the film soon centres on Yvon, and it follows his progression from one setback to another, taking him from being a law-abiding member of society to a murderer.

Over his thirteen feature films (plus one uncharacteristic comic short, Les affaires publiques, 1934) you can see Bresson refining his filmmaking techniques. From his third feature, Diary of a Country Priest, he worked largely outside of studios and with non-professional actors, or "modèles" as he called them, intensively rehearsed to remove any traces of theatricality or "acting". There's little or no internal psychology to be learned: all we know is what we observe the characters say and do, and attention needs to be paid as Bresson doesn't show us more than he absolutely needs to. Or doesn't show...often the "action" will be offscreen, with the soundtrack doing as much of the work as the image. See for example, an altercation in a cafe is played out on a shot of a hand and then an overturned table. Later on, a slap – with more impact due to its place on the soundtrack – is offscreen, and we're shown its impact in a closeup of the cup of coffee the person slapped is carrying. Some scenes in the film which another filmmaker might have made into elaborate setpieces are intentionally de-dramatised: a bank heist and shoot-out followed by a car chase, an axe murder.

As said above, Bresson's modèles were non-professionals, even if some of them did go on to further acting careers. (Elise, Yvon's wife, is played by Caroline Lang, the daughter of French politician Jack Lang.) However, behind the camera Bresson worked with some of the leading names in their fields at the time. His production designer on L'argent is Pierre Guffroy, who had worked as an assistant for Bresson on The Trial of Joan of Arc and full production designer on Mouchette. By the time L'argent was made, he had won an Oscar for his work on Tess. Bresson also had professional relationships with several cinematographers, beginning with Léonce-Henri Burel (a veteran of the silent era) on the four films from Diary of a Country Priest to The Trial of Joan of Arc. Then there were three with Ghislain Cloquet, which took Bresson from black and white to his first colour film, Une femme douce. Following one film shot by Pierre Lhomme (Four Nights of a Dreamer), Bresson worked on his final three features with the Italian Pasqualino De Santis, who had worked regularly with Visconti among others. By all accounts their collaboration was at times stormy, not helped (or maybe indeed helped) by the fact that neither man was particularly fluent in the other's language. Yet they continued to work together. De Santis's work is very much attuned to Bresson's aesthetic, intent on simplifying things as far as possible and using natural light, or a simulation of it, as much as possible. (The great exponent of this kind of shooting style was the Spanish DP Nestor Almendros, who worked extensively with Eric Rohmer – a filmmaker himself influenced by Bresson – and François Truffaut. I don't know if there was ever any question of Almendros and Bresson working together, but the results would have been fascinating if they had.) Bresson and De Santis aim for each shot to be "necessary" rather than indulging in most likely superficial beauty – yet the results are often beautiful. While Bresson's films are not visually spectacular in the way most people would think, they do benefit from the big screen, and not just for the impact of the soundtrack. (Even on a large-screen TV you might struggle to read Elise's letter to Yvon, but fortunately we have subtitles to help us.) The difficulties of the production meant that De Santis ran out of time and had to move on to another film, so his work was completed by Emmanuel Machuel, who had previously worked for Bresson in Cloquet's camera crew for Au hasard Balthazar, Mouchette and Une femme douce, and both are credited.

L'argent premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 1983, with Bresson sharing the prize for Best Director with Andrei Tarkovsky for his penultimate feature, Nostalgia. (The Palme d'Or went to Shohei Imamura for The Ballad of Narayama.) Bresson had plans to make a further film, based on the Bible and to be called Genesis, but this never came to pass, and clearly his age and health was a factor in this. He died in 1999 at the age of ninety-eight.

L'argent is the third of three Bresson films released by the BFI on Blu-ray, along with Pickpocket and The Trial of Joan of Arc. The disc is encoded for Region B only. The film was a PG on its original release and a previous BBFC pass for homeviewing, though in 2022 it was uprated to a 12. That certificate may also apply to the short Value for Money, though at the time of writing it doesn't appear on the BBFC website, and appears not to have been submitted to the Board at the time of its original release.

The film was shot in colour on 35mm stock, and the Blu-ray transfer is in the intended ratio of 1.66:1. While I had seen L'argent once before watching it for this review, that was Channel 4's broadcast of 1985, so I can't comment on the look of the film, but the transfer does tend towards the yellow. It does not do so as much as some restorations of other films out there, and remains plausible for a colour film of the time, and neither Bresson nor De Santis are still with us to be consulted.

The soundtrack is the original mono, rendered as LPCM 2.0. Previously, Bresson had made striking use of non-diegetic music, usually from the classical repertoire (Lully and Fischer in Pickpocket, Mozart's Great Mass in C Minor in A Man Escaped, Monteverdi's Magnificat in Mouchette), by the end of his career he had eschewed it. So in L'argent there is no non-diegetic music, and only one diegetic example, a piano performance of Bach's Fantaisie Chromatique). As mentioned, the sound carries the narrative as much as if not more than the images, and and an intrinsic part of that sound is the silence that surrounds it. Dialogue and those sound effects are clear and well balanced. English subtitles are optionally available, for the feature and the trailer.

Style, Anti-Style and Influence (22:31)

Another item from the BFI Southbank's Bresson retrospective of June 2022. Geoff Andrew interviews Jonathan Hourigan and Nasreen Munni Kabir, both of whom had worked with Bresson, at different times, on L'argent and Four Nights of a Dreamer respectively. Kabir found Bresson somewhat intimidating. She went on to work in the Indian film industry. Hourigan talks about how he discovered Bresson by reading about the films, when they were hard to see in the UK. Channel 4 did show some of the films after it was launched in 1982, but before then showings were intermittent, just seven of them on the BBC between 1969 and 1977, including three films (Mouchette, Une femme douce and A Man Escaped) one a week in the BBC2 World Cinema slot in 1973. Hourigan helped to organise a retrospective at the Electric Cinema in 1981, which was his first opportunity to see many of them.

First and Last (9:14)

From the same retrospective, Peter Hourigan compares L'argent, with Bresson's first feature, Les anges du péché (1943), with many correspondences between them, their last shots in particular. However, the effectiveness of this item is mitigated by the fact that the BFI do not have the rights to Les anges du péché so the extracts from it have been removed.

The Root of All Evil (18:53)

Michael Brooke, who contributed an overview of Bresson's films and career to the Pickpocket booklet, provides a video essay on L'argent. With Brooke speaking a voiceover over extracts from the film, he makes a persuasive case for the film's being one of Bresson's greatest. There's a spoiler warning at the start, so watch it after you've seen the film.

Jonathan Hourigan on L'argent (26:01)

From 2007, Hourigan speaks about L'argent, largely an account of his work on the film. It appears to have been an uncomfortable experience, being shot in the middle of a hot Parisian summer, often in cramped conditions involving hot lights. Hourigan takes questions (much more audible than they often are in archive recordings) before a moderator (unidentified, female) wraps things up. This plays as an alternate soundtrack to the main feature, and gives way to the film sound after it finishes.

Trailer (0:27)

After the lengthy, quote-heavy trailers for Bresson's previous films, it's interesting to come across what is really a teaser. If the style of the features has been pared down over time, maybe the means of selling them has too?

Value for Money (21:54)

Another BFI extra that's not connected to the main feature but is tangential to its themes, though that's really just the title. This is a surreal BFI Production Board short film from 1970, shot in black and white, in which a young woman (Elizabeth Mellor) finds a mysterious coin-operated device on the beach. Also in the cast is Quentin Crisp. Its director and cowriter David Blest does not appear to have made another film (he, and indeed the film, do not have an IMDB entry at the time of writing), and according to the booklet notes was primarily an arachnologist. However, there are some more familiar names behind the camera. Franc Roddam was the executive producer, while the co-writer, provider of the story and cinematographer was Gale Tattersall, at the start of a long career as DP and camera operator.

Booklet

The BFI's booklet, available with the first pressing only, runs to twenty-four pages. It begins with "A Chat and a Glass of Water" by Peter Hourigan, written forty years to the day after the start of principal photography of L'argent. He details how he came to see Bresson's films by reading about them and then tracking down screenings, often in battered 16mm prints. (Une femme douce, which tends to be regarded as one of Bresson's more minor films, is a particular favourite.) He contacted Bresson, interviewed him, and then organised a retrospective at the Electric Cinema in 1981. This resulted in his travelling to France to be an assistant in the shooting of L'argent. Hourigan's piece includes extracts from letters from Bresson to him.

Dr Martin Hall talks about Bresson and L'argent, a film which he regards as the success that his previous films ("attempts" as Bresson said) had been working towards and which he interprets as a study of capitalism and its victims. After full film credits, the booklet reprints Tom Milne's review from the July 1983 Monthly Film Bulletin and provides notes on and credits for the extras.

Although it wasn't intended to be Bresson's final film, L'argent does feel like a culminating work, a final synthesis of the themes and style he had been working towards over a forty-year feature career. It is well served on this Blu-ray, one of three Bresson films released in this format by the BFI.

|