|

Clyde Griffiths (Phillips Holmes) is working as a bellboy when his wealthy uncle Samuel (Frederick Burton) stays at the hotel. Clyde persuades Samuel to give him a job and so he moves on to a shirt factory in New York State. There, he meets Roberta Alden (Sylvia Sidney), known as Bert, and they become an item in secret. Meanwhile, Clyde, looking to advance himself, meets and falls for debutante Sondra Finchley (Frances Dee). However, Bert soon finds out that she is pregnant...

An American Tragedy, based on Theodore Dreiser’s novel, was made during Josef von Sternberg’s run of seven feature films starring Marlene Dietrich, in fact between the third, and second in Hollywood, Dishonored (1931), and the fourth, Shanghai Express (1932). With its lack of commercial success and the presence of leading actors less to be conjured with, it has tended to be overlooked. However, it is certainly worthy of consideration with the rest of its director’s output.

Dreiser (1871-1945) was a leading American novelist of the naturalist, or social-realist, school. Beginning as a journalist and a committed socialist, he brought a journalist’s eye to his fiction, with an intensely detailed look at his characters and the society which contains them, and the forces which work on them. Dreiser’s novels and short stories were often controversial due to their content, which included sexual themes. His first novel Sister Carrie was published in 1900, but his first commercial success was An American Tragedy, some 800 pages long, in two volumes when it was first published in 1925. It was inspired by the real-life case of Chester Gillette, whose murder by drowning of his girlfriend Grace Brown in upstate New York in 1906 had made national headlines. Gillette was found guilty and was executed in the electric chair. While the novel was often criticised as being sordid, it was a bestseller. Needless to say, the cinema paid attention, and Paramount bought the rights to the novel. (Around the same time, his 1911 novel Jennie Gerhardt was also sold to the movies, again to Paramount, their film coming out in 1933, also starring Sylvia Sidney. Sister Carrie was filmed in 1952 as Carrie, starring Laurence Olivier and Jennifer Jones, directed by William Wyler.)

The first director in line to make the film of An American Tragedy was none other than Sergei Eisenstein, at the height of his fame from his films made in Russia. Dreiser approved of this, having met the director on a visit to Russia. However, Eisenstein’s treatment of the story, overtly deterministic and avowedly Marxist, did not find favour. Josef von Sternberg was hired in his place to develop the film from a new screenplay by Samuel Hoffenstein. Dreiser took exception to the way that they deviated from his work, removing most of the sociological aspects of the story and making it as clear as could be done at the time that Clyde Griffiths’s motivations were more rooted in sexual desire and the sexual hypocrisy of the time. It’s clear from the outset that Clyde is desirable to many of the women he meets, and he’s happy to reciprocate. As this film was made in the Pre-Code era (more of which in a moment), von Sternberg and Hoffenstein were able to make a film where sex is a driving force. It’s not exactly subtle, with a cut to Clyde and Bert sitting at a table, him smoking a cigarette, making it very clear what has just happened, even if they wouldn’t have been able to specify it explicitly.

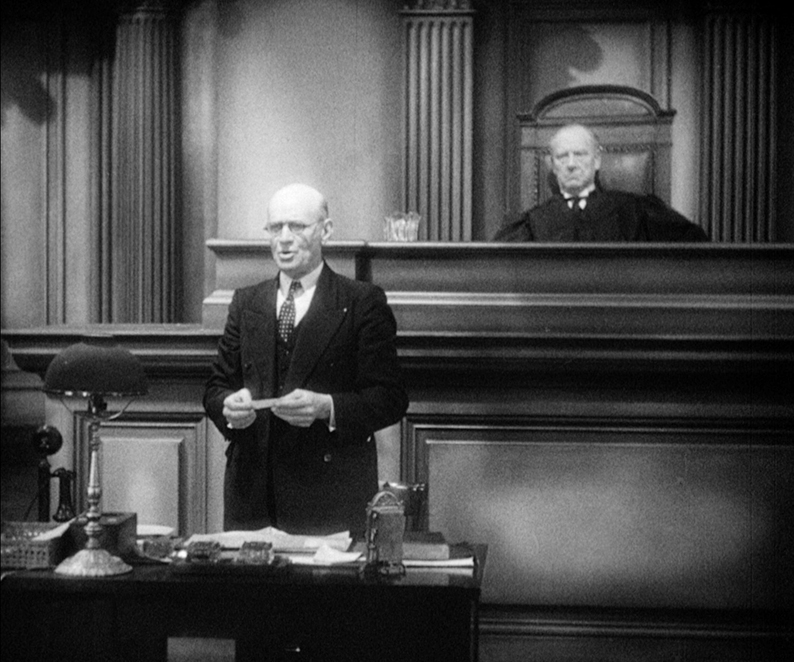

The film falls into two unequal sections, with the final half-hour dealing with Clyde’s court case and its aftermath. The first part, or rather two-thirds, is the stronger. The film was made two years after the release of the first all-talkie, and in some ways An American Tragedy, like von Sternberg’s earlier crime drama Thunderbolt (1929, made in both silent and sound versions), shows the lingering influence of the silents that its director began his career in, especially in the use of captions bridging transitions in the story, silent-era intertitles in all but name. The camerawork – thanks to von Sternberg’s frequent collaborator Lee Garmes, one of the great Hollywood cinematographers of his time – is fluid, with none of the supposed limitations of early-talkie cinema, and there’s some strong location work (Lake Arrowhead, California) in the first half. The use of shadows conveys the story as much as the dialogue does. At the very end, the already narrow Movietone-ratio frame (see below) is narrowed still further, our protagonist trapped with it. By the time he made this film, von Sternberg had earned himself a reputation as a perfectionist, obsessed with fine details, but he delivered this film on time and on budget, a possible indication that he thought of the film as essentially a work for hire.

The leading actor was Phillips Holmes, who was a popular leading man of the time, but nowadays is probably not now thought of as a major star of the Pre-Code era. He can also be seen as the lead of Ernst Lubitsch’s Broken Lullaby (1932, also on Blu-ray from Indicator). However, a series of flops and a car accident, leading him to be sued by actress Mae Clarke for allegedly driving while drunk, affected his career. He joined the Royal Canadian Air Force during World War II and was killed in a mid-air collision in 1942, aged thirty-five. He has the looks to play Clyde, though tends to be something of a blank the other characters, and we the audience, have to project onto. Sylvia Sidney is excellent, and at times heartbreaking, as the doomed Bert.

The Pre-Code era strictly speaking began with Will Hays’s first drawing up of his Code, a list of Don’ts and Be Carefuls for film producers, following concerns about the content of motion pictures in the later silent era. With the arrival of talkies, the possibility of salacious dialogue became another concern. The era ended in 1934 with the Production Code being enforced on the studios, but in between Hays’s strictures were often ignored by filmmakers, though they still had state censorship bodies to deal with. The references to pre-marital sex and pregnancy and to abortion in An American Tragedy led to censorship issues. Some states required the abortion references to be removed before they would pass the film. In South Africa, Italy and the UK, An American Tragedy was banned outright. How often it was shown in the UK after that is a subject for further research if that has not already been done. It was in non-theatrical 16mm distribution in 1975, when the Monthly Film Bulletin reviewed it in its December issue. It had its first UK television showing on 1 July 1979, late at night on BBC1. The film was still formally rejected at that point, and was not in fact passed until 2023 for the present Blu-ray release.

An American Tragedy was not a commercial success. Dreiser’s disapproval led to his unsuccessfully suing Paramount in a bid to have the film suppressed, and some new scenes were shot to appease him, whether or not by von Sternberg is unknown. Von Sternberg moved on to one of his finest collaborations with Dietrich (and with Garmes), Shanghai Express. An American Tragedy was remade in 1951 as A Place in the Sun, directed by George Stevens and starring Montgomery Clift, Elizabeth Taylor and Shelley Winters, an altogether glossier version, somewhat toned down due to the Production Code still being in effect.

An American Tragedy is released by Powerhouse as spine number 267 in the Indicator series, a Blu-ray disc encoded for Region B only. As mentioned above, the film was rejected by the British Board of Film Censors (as was) in 1931 but now carries a PG.

The film was shot in 35mm black and white and the early-talkie “Movietone” aspect ratio of 1.19:1. (Briefly: silent films were 1.33:1, but when the talkies arrived and when soundtracks were printed on film, this reduced the width of the frame, resulting in the narrower ratio. This however was too close to a square to be aesthetically desirable for many filmmakers, so the frame lines were widened, so producing a wider ratio, the Academy Ratio of 1.37:1. Academy was standardised in the US in 1932, though the reason for the slight difference between the old 4:3 and this is unknown. This new ratio was used for the next two decades.) Indicator’s Blu-ray transfer, in the correct ratio, derives from a 2019 restoration by Universal (who own almost all of Paramount’s catalogue from this era), which was created from a 4K scan of a composite finegrain print. We’re a few generations away from an original nitrate negative (which presumably no longer exists, ninety-plus years later), but what we have is good. It’s a little soft, along the lines of other nitrate-shot films of the time, but there’s plenty of naturalistic grain and contrast and greyscale look fine.

The soundtrack is the original mono, rendered as LPCM 1.0. With any film from this era you do have to factor in the limitations of early sound technology: not much of a dynamic range and a certain amount of hiss on the track. That said, this track, restored at the same time as the picture, is more than acceptable in its rendering of dialogue, music and sound effects.

English subtitles are available for the hard-of-hearing and I spotted no errors in them.

Commentary by Josh Nelson

Newly recorded for this release, Josh Nelson’s commentary begins by addressing a few issues: that this is a Pre-Code film, but isn’t the permissive free-or-all that some people assume that era of American cinema to be. Nelson admits that the film is somewhat overlooked, in part to its being overshadowed by von Sternberg’s Dietrich collaborations and its lack of availability for some years. (With the enforcement of the Code, films in release at the time, or older films looking to be reissued, could only continue to be shown if the Administration approved that. Some films were cut going forward – see for example, Love Me Tonight, where the cut material does not survive – and anything considered beyond the pale had to be withdrawn.) While he acknowledges the role that sexual attraction plays in the story, Clyde’s pursuit of Sondra is as much to do with a bid for social advancement. This isn’t the most scene-specific of commentaries, with Nelson spending a lot of time discussing the film’s production and its themes, but it does have its moments: for example, a big close-up of Sylvia Sidney leading into an appreciation of her career. Nelson considers her the beating heart of the film, and this was a breakout role for her. She certainly disliked von Sternberg, though, and thought he was a man with no regard for actors. Nelson also talks about Dreiser’s legal tussles with Paramount, and about Phillips Holmes’s faltering career a few years later. There are few dead spots in Nelson’s commentary and it’s a dense one as he clearly has a lot to say. Much of what he says is certainly well worth listening to.

Josef von Sternberg oral history (26:17)

Von Sternberg, interviewed in 1958 by George Pratt, begins by saying that he is not well disposed to talking about his own work. After a caption clarifying that this interview was not intended for public consumption and has quite a few limitations in its recording and is unedited, it is presented on this disc against a black screen.

He believes that the creative artist is not the best judge of his own work, but doesn’t disregard the possibility that a student of his work may ascertain things that the creator was not aware of. His work was an exploration of various subjects and their interpretations, in some ways a test of the impact of his control over the medium. He regards this period of testing lasted half a decade, from his first film in 1925 until he made The Blue Angel in Germany in 1930. He talks more about his later career than he does about the Dietrich years, and says he took a while before he found a subject which engaged him, and made Anatahan in 1951, which he had to direct through an interpreter as he spoke no Japanese. However, the Japanese disliked the result. He is very conscious of the effectiveness of the film medium, and there’s a sense of the value of his words for posterity, particularly to scholars of cinema.

Lee Garmes oral history (88:55)

This interview was also conducted in 1958 by George Pratt. After a similar caption to the von Sternberg interview, this is presented differently, as an alternate audio track on the main feature rather than against a black screen. It is also unedited, beginning with the sounds of microphones being set up and ending with several short items intended to be inserted in particular parts of the interview we have listened to.

Three times longer than the von Sternberg oral history, this is more an overview of Garmes’s career than a more general discussion of his work and principles. Born in 1898, he entered the film industry working for Thomas Ince, at first in the paint department and then becoming a camera assistant and then a cinematographer. He worked for a while with Rex Ingram, and there’s a passing mention of Michael Powell, who was also working for Ingram at the time. While much of his most highly regarded work was black and white, he was one of the credited cinematographers on the 1930 comedy Western musical Whoopee!. shot in two-strip Technicolor. Relevant to this release is a discussion of his work with von Sternberg, whom he describes as a “caustic man” and points out that his camera operator particularly disliked him. We do hear about Phillips Holmes’s disputes with the director. Garmes had worked with von Sternberg before on Morocco (1930) and Dishonored (1931) and went on to shoot Shanghai Express (1932), which won him his only Oscar. He is also prompted to talk about the aborted von Sternberg film I, Claudius. Garmes also worked with Rouben Mamoulian and Howard Hawks and his contribution is a particularly notable part of Zoo in Budapest (1933). He seemed to have been forward-thinking with regard to film technology, tackling VistaVision (albeit in black and white) with The Desperate Hours (1955). It’s beyond the scope of this interview, but he was also an advocate of video cinematography as early as 1972. Lee Garmes died in 1978.

An American Picture (28:20)

As he did for Indicator’s previous von Sternberg releases Thunderbolt and Jet Pilot, Tony Rayns provides an overview of the film in question. (He also provided a commentary on The Scarlet Empress in Indicator’s Marlene Dietrich & Josef von Sternberg at Paramount box set.) He begins by addressing von Sternberg’s reputation as a spendthrift, which began with his rivalry with Ernst Lubitsch, but also points out how efficient he could be when he needed to. Rayns then talks about Dreiser’s novel, Eisenstein’s involvement with the proposed film version and von Sternberg’s then attachment to the film. The thought of replacing Eisenstein on a film might have appealed to his not-negligible vanity. Rayns discusses the film’s visual style and narrative methods, while pointing out that it’s a very linear treatment of the story, with nothing extraneous to the narrative.

Nurture & Nature (7:55)

Tag Gallagher’s visual essay asks the question as to which of the two attributes of the title is most responsible for the protagonist’s actions. Certainly some of the characters, including Clyde’s mother, believe it’s primarily the former. But maybe the latter plays more than a part. Dreiser tackled this in his novel in lengthy chapters which the film distills into short scenes. Gallagher points out that this is an unusual film in that the sexual attractiveness of a man, rather than that of a woman, is the motor of its story, however wooden he might be. External nature also plays a part, with repeated imagery of water, leading up to the key event of the film taking place on a lake. This is a short piece; you could easy see it going on longer.

Image gallery

Thirty-eight stills (all black and white), lobby cards and poster designs, including two Swedish examples of the latter for En amerikansk tragedi.

Booklet

Indicator’s booklet with this limited edition runs to forty pages. First up is “The Tragedy of Desire” by Imogen Sara Smith, which begins by calling the film as “written on water”, from the opening credits onwards. She quotes Dreiser’s novel: Clyde has a “temperament that was as fluid and unstable as water”. Smith gives an account of that novel and Paramount’s making of the film version, including the conflicts between Dreiser and von Sternberg. She also discusses the visual style of Von Sternberg and Garmes and how that contributes to the film.

Jeff Billington contributes “Eisenstein’s American Tragedy”, which begins with the director’s trip to Western Europe, following the controversy at home over his latest film, October (1928). Due to his earlier films Strike (1925) and Battleship Potemkin (also 1925) he was internationally famous. He was also looking into the possibilities of the new sound technology. He met Josef von Sternberg in Berlin while the latter was making The Blue Angel. Others he met on his travels included Hitchcock collaborator and Communist sympathiser Ivor Montagu in London, and in Paris James Joyce, Jean Cocteau and Abel Gance. In 1930, he received an offer from Paramount to make a film in Hollywood and the result did not prove to be An American Tragedy, as we have seen. Eisenstein’s experiences were described in Montagu’s book With Eisenstein in Hollywood, and Billington quotes from Eisenstein’s draft screenplay, an opening scene displaying his theories of the use of sound and image in counterpoint to each other. The result was too avant-garde for Hollywood at the time, and despite some enthusiasm Paramount passed on it. Eisenstein, his contract cancelled, returned to the USSR. He thought von Sternberg’s film was so poor he was unable to finish watching it.

Von Sternberg is next, with an extract from his autobiography Fun in a Chinese Laundry (1965). As well as discussing his taking over of the project from Eisenstein, he also talks about his clashes with Dreiser. To Dreiser’s accusations of distorting his material, he would point out that his script was actually very faithful to the novel, even to the point of reproducing much of its dialogue.

From the 9 August 1931 edition of the Cincinnati Enquirer, in “Novelist Wars” Herman J Bernfeld recounts Dreiser’s unsuccesful lawsuit against Paramount, as to whether the film was a fair representation of the book.Among the witnesses for the prosecution were Patrick Kearney, who had adapted the novel for the stage in 1926 and found the film a “gross misrepresentation” of Dreiser’s work. (A Place in the Sun is adapted from his play as well as from the original novel.)

The booklet also includes transfer notes and plenty of stills.

Not a success on its release, An American Tragedy has tended to be overshadowed by Josef von Sternberg’s films with Marlene Dietrich made before and after it, not least by the presence of a more distinctive leading actor. It has also been overshadowed by its 1951 remake, or second adaptation of the same novel, A Place in the Sun. However, it proves to be a film of considerable merit in its own right, and so thanks to Indicator for bringing it out.

|