|

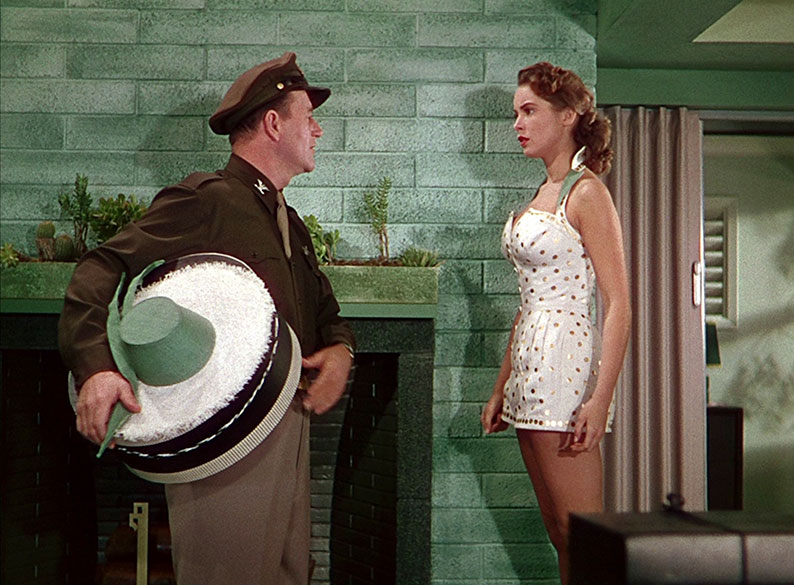

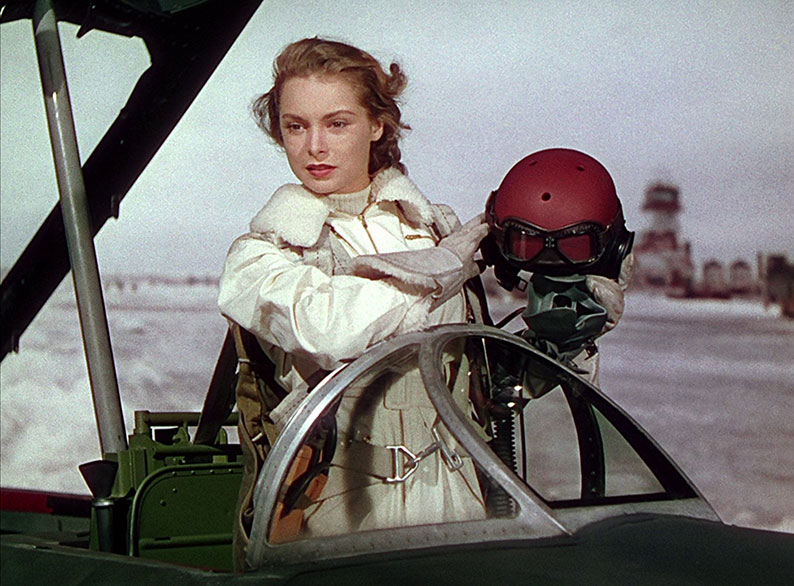

America, the late 1940s (more or less). A Russian jet lands on an American airstrip, its pilot intending to defect. Base commander Jim Shannon (John Wayne) goes out to the plane...to find out that its pilot is a woman, Anna Marladovna (Janet Leigh). Jim is immediately attracted to her and to avoid her being deported, he marries her without official permission. But is she who she says she is?

Jet Pilot was the second-to-last film that Josef von Sternberg directed, his only one in colour. It became his final film to be released after seven years on the shelf. Von Sternberg disowned the film, and it clearly bears the signs of post-production tinkering by producer Howard Hughes (who gets a “presented by” credit). It wasn’t a critical or commercial success, and is far from von Sternberg’s best work, but given his involvement it’s certainly of interest. It was however, reportedly Hughes’s favourite film, one he watched repeatedly, so you might be glad he at least was happy with it.

The Soviet Union and the USA had been on the same side in the World War which had ended just four years before Jet Pilot went into production, but now we’re in the Cold War. Jet Pilot is hardly the most in-depth film dealing with American/Soviet tensions, which here become pretty much a backdrop for a both-sides-of-the-tracks (or would that be both sides of the Iron Curtain?) romance. Realism was never von Sternberg’s mode, but it’s fair to say that that’s not on the agenda here. Janet Leigh doesn’t even attempt a Russian accent. The film is entirely anglophone, with a couple of short scenes with Russians together having them conversing in English. (To be fair, foreign characters speaking in their own languages with English subtitles was not the practice in Hollywood at the time. One film which did change that was The Longest Day, but that was a decade and a half in the future.) The production design does make a concession to foreignness, though, with the scenes set in Russia having signage in the Cyrillic alphabet.

In the opening credits, third billing after Wayne and Leigh goes to the United States Air Force, and you sense there lay much of Howard Hughes’s attraction to this project and the finished film. The flying footage is indeed first-rate and makes the film a must-see for plane buffs, whatever the film’s other dramatic and comedic qualities. The flight scenes were shot at three different air force bases in California, with George Air Force Base standing in for Russia. Chuck Yeager, the first man to fly faster than sound, flew a Bell X-1, the plane in which he had broken the sound barrier, for the film. Over twenty-four hours of flying footage was shot. Given Hughes’s sideline as a bra designer (for Jane Russell most notably), the film even gets in a tit joke. Hughes even had involvement in the underwear Janet Leigh wears in this film. Jet Pilot has a fair amount of Production Code-friendly sauciness, though nothing compared to what von Sternberg had got past the censors in the Pre-Code era. Leigh and Wayne play the comedy well, not something you immediately associate with the latter.

Jet Pilot was written by Jules Furthman, who was also the credited producer other than Hughes. Furthman had worked with von Sternberg for many years, as far back as The Docks of New York and The Dragnet in silent days and including Thunderbolt, which was released by Indicator simultaneously with Jet Pilot. Furthman and von Sternberg worked on three of the latter’s films with Marlene Dietrich (Morocco, Shanghai Express and Blonde Venus) and the non-Dietrich The Shanghai Gesture. Production began in late 1949 but was not a happy experience, with according to von Sternberg much interference from the production office. The last footage in the film was shot in 1953 but Hughes continued to tinker with it and the film was finally released in the USA on 25 September 1957.

By that time, everyone involved had moved on. Von Sternberg had directed his final film, Anatahan, shot in Japan and released in 1953. He spent the rest of his career teaching film aesthetics at the University of California, Los Angeles. (Two of his students were Jim Morrison and Ray Manzarek, one half of what would become The Doors, and they refer to von Sternberg in their songs.) Wayne, who had taken on the film because it might make a political statement, thought that it was one of the worst he ever made. By the time the film was released, there had been something of a thaw in relations between East and West, and much of the flight footage had had to be removed as it was now technologically out of date.

Hollywood had changed too in the meantime. RKO, who had produced Jet Pilot, had by 1957 closed down its domestic distribution, so the film was released by Universal. Also, 1957 was four years after American studios had gone widescreen. Von Sternberg and his DP Winton C. Hoch had shot the film in the then-current Academy Ratio (1.37:1) but by 1957, Academy was obsolete for commercial features and the great majority of cinemas could no longer show it, so Jet Pilot was shown in the new standard ratio of 1.85:1, cropping the shots at the top and bottom throughout the running time. Viewers would not see the film in the ratio that von Sternberg intended until it showed on television.

How well Jet Pilot would have done if it had been released seven years earlier is a moot point, but in 1957 it seemed as dated as it inevitably was. Wayne and Leigh are hardly one of the great screen couples, but their banter is entertaining in its lightweight, faintly of-its-era-sexist way. Winton C. Hoch was one of the Hollywood studio system’s masters of colour cinematography, winning three Oscars. Possibly uniquely for his time, he never made a black and white film. Shot in three-strip Technicolor, his camerawork is one of the film’s major assets. Though the film has its defenders, it’s hard to say that Jet Pilot is more than a minor work in its director’s filmography. Aficionados will still seek it out, but maybe not so many others.

Jet Pilot is spine number 293 in the Indicator series, a Blu-ray encoded for Region B only. Jet Pilot was given a U certificate by the BBFC on its cinema release, and retains that rating. The Town is a documentary exempted from certification, but it had a U on its UK cinema release in 1944.

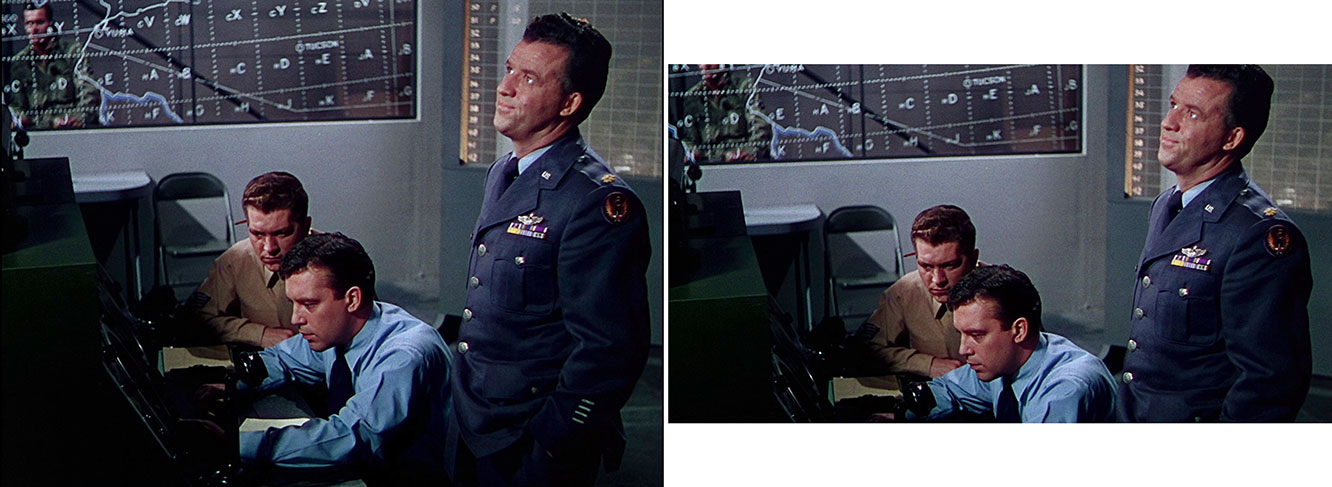

As mentioned above, Jet Pilot has two “official” aspect ratios, the 1.37:1 it was shot in and the 1.85:1 it was finally shown in when it was eventually released. Indicator’s release presents the film in both ratios and you can switch between the two using the Top Menu function on your remote. The film was shot in 35mm three-strip Technicolor and the transfer, in either ratio, looks pretty much like a three-strip film of the era does: strong, saturated colours (though not here especially highly saturated) and a sharp image with not a huge amount of grain. The flight footage is grainier and I’m wondering (but haven’t been able to confirm) if they were shot three-strip as well – which would have needed the bulky camera to go up in a plane to shoot the footage – or maybe used the single-strip Technicolor monopack. By the time Jet Pilot was released, shooting in three-strip had come to an end in Hollywood. For the screengrabs in this review, I’ve used the version in the ratio its director intended, but by means of comparison between the two presentations, see below.

The soundtrack is the original mono, rendered as LPCM 1.0. We are talking old-school Hollywood technical expertise here, and there’s nothing untoward, with the dialogue, music and effects all to the fore. English subtitles for the hard-of-hearing are optionally available for the feature and The Town, and I detected no errors in them.

Something in the Air (29:42)

In a companion piece to his featurette on Indicator’s Thunderbolt disc, Tony Rayns takes a look at Jet Pilot. The Thunderbolt featurette is longer and gives a broad view of von Sternberg’s career, but here Rayns talks about how the director is generally felt not to have matched his work earlier in his career, particularly his seven-film collaboration with Dietrich. Rayns discusses Jet Pilot’s lengthy production and even longer post-production and Howard Hughes’s influence on the film, in an informative and sometimes quite droll piece to camera. The film clips are shown in 1.85:1.

Textless opening sequence (1:31)

As it says, or a minute and a half of jet porn for your viewing pleasure. Presented in 1.37:1.

Theatrical trailer (2:50)

You’d normally expect a trailer to concentrate on the stars of the film you want people to pay their hard-earned dollars to see, but no, front and centre here is Howard Hughes. He defied convention and set new patterns for others to follow. A head shot is flanked by two women in ball gowns. He also, says the voiceover, left the world a legacy of film classics and this is one of them, as it intends to show from clips. This is presented in 1.78:1, slightly narrower than 1957 audiences saw the film.

Image gallery

Advanced via the NEXT key on your remote, this is a gallery of seventy-two images: stills (black and white and colour both), lobby cards, a press kit synopsis, advertisement designs and posters from various countries. This is where you find out that the French knew the film as The Spies Amuse Themselves (Les espions s’amusent).

The Town (11:27)

For such an avowed non-realist as von Sternberg, a documentary is the last thing you’d expect. However, this short film was made in 1943 as number four in a series called The American Scene, an initiative of the Office of War Information to celebrate the American way of life, both at home and in countries both occupied or at risk of occupation by the enemy. This was von Sternberg’s contribution to the war effort and his only film between The Shanghai Gesture in 1941 and the start of production of Jet Pilot. Working from a script by Joseph Krumgold (no one is credited), von Sternberg takes us round Madison, Indiana, showing us the buildings and the surrounding countryside, and the people, many of whom hailed from Europe – all of them white. The Town was very much work for hire, but you can still see the director’s hand in some shots and sequences.

Booklet

Indicator’s booklet with this limited edition runs to thirty-six pages. It begins with the wordily titled “Everything and Nothing: Musings on the Possibly Ineffable Qualities of Jet Pilot”, an essay by Glenn Kenny. It begins by citing the French-born director Robert Florey describing (in 1960) von Sternberg as “one of the few geniuses of the movies”, but regretting the ones that got away: A Woman of the Sea (1926, previewed once and then destroyed by its producer, Charles Chaplin), Macao (1952 – von Sternberg was fired and the film partly reshot)...and Jet Pilot. Kenny then cites Andrew Sarris’s description of the director’s work as “cinema of illusion and delusion”, and the way that von Sternberg seemed a little lost when he was no longer working with Marlene Dietrich. Often there was outside influence interfering with him, and in the case of the film at hand it was Howard Hughes. Kenny details Hughes’s post-production tinkering, his getting his beloved flight footage down to a manageable amount for a feature just under two hours long. Kenny then goes on to discuss the film’s reception, its lack of success initially and its rehabilitation by some critics, including those of the French New Wave. François Truffaut called it “a good film in spite of itself” and Jean-Luc Godard claimed it influenced his own A Woman is a Woman. Kenny himself doesn’t make huge claims about Jet Pilot, though he regards it as “one of the most exhilarating films about nothing ever made”.

Next up is von Sternberg himself, giving Jet Pilot fairly short shrift in his autobiography Fun in a Chinese Laundry. And the man himself appears again in a couple of print interviews, the first from 1950 in Hollywood magazine, with columnist Gene Handsaker making an issue of the fact that Jet Pilot, then in production, was the director’s first feature film in eight years. And in the Atchison Daily Globe in the same year, Erskine Johnson finds the director in combative mood and seems more interested in Janet Leigh. Also in the booklet are contemporary film reviews, with pans from the Monthly Film Bulletin and the New York Times, but more positively from Cahiers du Cinéma. Finally, there are credits and an unsigned one-page note for The Town.

A singularly benighted production, Jet Pilot is a test case for adherents of the auteur theory, given that while Josef von Sternberg’s hand is certainly in evidence, the thumbprints of producer Howard Hughes are all over it. The result is far from von Sternberg’s best work but will still be of interest, and it is presented well (including the two historically accurate aspect ratios) on Indicator’s disc.

|