|

On the day that the news of the death of hugely influential Swiss surrealist artist H. R. Giger was announced to the world, Camus and Slarek offer a brief but heartfelt trubute to a man whose work touched them both.

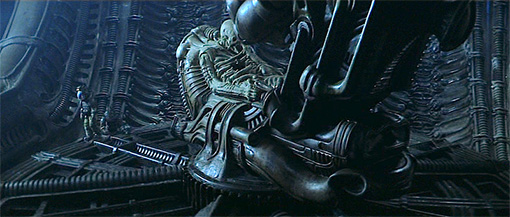

'Giger's involvement in the film was assured when its director,

Ridley Scott, arrived for his first meeting at Fox and was shown

a new art book called The Necronomicon. "I took one look at it,"

says Scott, "and I've never been so sure of anything in my life."' |

Interview with the artist, Starlog Magazine No. 26, 1979 |

Scott's quote above is perfect. You see these morbid, beautiful, sado-masochistic, body piercing, literally penetrating creatures brought to hideous life in shades of that indefinable industrial grey and two things happen. Firstly, you seriously question the mental health of the artist and secondly, if you were making a movie about a real monster that ticked every primal box in human terror, look no further. 2D designs change once having to be rendered in 3D as a practical suit but the original image (with huge black eyes this time) of the creature Scott saw in the surrealistic art book, H. R. Giger's Necronomicon, is just perfect in its incitement of repulsion, stunning in its detail, delicate almost until it rips your head off and it was set to change everything. Giger's work, once Hollywood trumpeted it loudly across the world, changed a tired aesthetic - monster design - into something vibrant and new. Giger's bio-mechanical style took over the design-id within film-making and the movies got their mojo back. There is no doubt that Giger's design was almost instantly iconic and now a shame, as noted in my movie review of Prometheus, that it's a Disneyland exhibit in Florida... Yes, the 'xenomorph' and its ilk may have become overused and therefore stripped of their power but a flick through the pages of that book that started it all still sends delicious shivers spider-legging north and south, vertebra by vertebra, on my spine. Giger's creatures were simply 'right' and Scott had the taste to recognise this.

I visited Giger's personal Museum of Art (allow me the Withnailian excuse) 'by accident'. In 2004 I was in Switzerland visiting relatives. We were all bound for Gruyere because most of our party had an interest in seeing how the famous cheese was made. Alas, not me. Next-door was the Giger Museum of Art. My double take was as ridiculous as John Cleese's as he spies the wooden 'Trojan' rabbit in Monty Python and the Holy Grail. A cheese-making factory. H. R. Giger's Museum of Art. Things were not making a lot of sense (of course, the man had to live somewhere and he was Swiss so I was in the general vicinity). And then we stepped into the café. Ah. OK. Yes. The walls were made of grotesque babies, there were alien head lampshades, and there were many curled bone chairs etc. Oh, I knew whose hands we were in. To say I was delirious with pleasure was an understatement. And I did warn my party that if they paid their money and went inside the museum, it was not all Starry Nights, Chagall and fruit by Cézanne. This was the man who manufactured the original nightmare, the man whose hellish forms have as much of a relationship to what may be regarded by some narrow minds as pornography as they do to pain and suffering. Well, I paid a small price for exposing some of my party to Giger's world but the abiding memory I have of the experience is turning the corner into the first corridor and aside from all the extraordinary and frankly nasty art adorning the walls, there was, in front of me, in a tall man-sized glass case, some fashioned material that a Nigerian student wore for a number of weeks in 1978 and 1979 and subsequently, so attired, scared the shit out of moviegoers the world over. The original suit, worn by Bolaji Badejo, stood in front of me in a standing pose. I may have pressed my face against the glass. I took it all in. Something primal stirred in me because I was this close to the DNA of my own nightmares. The rest of the art on offer was intriguing (lots of designs for movies that never were - Jodorowsky's Dune would have changed cinema history - see the doc). But pornography (in inverted commas) was well served and in this artistic context it never seemed pornographic (such a narrow definition for this work) but it was suitably unsuitable and I left Gruyere excited but chastised. As far as my party was concerned, it was Hans Rude Giger...

Bob Hoskins died and we acknowledged that sad event. Slarek then wondered why we didn't make that kind of appreciation part of the site's remit. After all, our heroes were rapidly diminishing in number. This afternoon came the news that the man responsible for a good many nightmares, H. R. Giger, had died falling on stairs. Two days ago in an art centre of all places, I asked Slarek what was it about Giger's work that was so attractively terrifying. He mentioned the primal nature of the man's work and how it bypasses any screens of psychological protection. I thought God must have said to the artist, "I put the deeply embedded, primal fear response in this part of the mind of some of my apes. Right here, see?" H. R. nodded. He now knew exactly where to aim.

He will be mourned, missed and acknowledged by many as the creator of the greatest movie monster movies have ever seen. His impact on my own psyche has been profound and I love the man for that. Damage me with light and I'll accept that as an invitation to dance with the devil. And what a dance. Thank you, Hans Ruedi. Thank you.

I sometimes wonder if a painter and sculptor of Hans Ruedi Giger's singular talent and imposing reputation ever found it amusing that of all the great work he created over the years, he remains to this day most famous for designing the scariest monster in science fiction movie history.

As an student just two years out of art school I should certainly have been aware of his work before sitting down to be terrified by Alien the first time, but I wasn't. Then again, our art history lessons had been precisely that, detailed examinations of major artists and art movements of the past. In those days before the rise of the Young British Artist, we rarely seemed to talk about current trends, and only got to view them on termly gallery visits. But the lessons were still fascinating and often revelatory. In the course of the year's study I discovered the delights of Impressionism, Expressionism, Futurism, Dada, the Bauhaus and a whole slew of others. But my first and truest love was always Surrealism. To my surprise, my art history lecturer was not a big fan, in part because it seemed to be the only artistic movement that most students had heard of before joining the course. He also believed that we arrived with severe misconceptions over what Surrealism was actually about. It turned out he was right, but what I learned on the course only deepened my devotion.

Watching Alien was one of the only times I've been startled and disturbed by the production design. The interior of the alien ship had me chewing my knuckles, and the creature itself, in the brief but terrifying glimpses we were given of it, felt like something had torn from my nightmares. This is the essence of the Surrealist ethos, a physical realisation of the subconscious and the dream world. But these were not good dreams. These were the ones that woke you in the night and left you sweating, that lived in the shadows in the corners of darkened bedrooms. It thus did not completely surprise me to discover that H.R. Giger, the man who had created these unsettling images, used to suffer from the sleep disorder that is colourfully known as night terrors.

As Camus mentions above, Giger's first film supposed to be Dune for Alejandro Jodorowsky, for which the artist completed a number of startling designs. But the project fell through, only to be revived years later with fellow surrealist David Lynch in the director's chair. Only a small number of Giger's rough concepts were retained, which is ironic really, given that Giger was a huge fan of Lynch's astonishing first feature Eraserhead and was apparently keen to work with the director.

Maybe it doesn't matter that we discovered Giger's work through a Hollywood movie. What really matters is that we did discover it, and that once we had we just lapped it up. All of my closest friends of the past twenty years own (or in the case of late friends, once owned) books of work by this Swiss surrealist, volumes that we intermittently take off the shelf to admire, to stoke our imagination or to startle unwary visitors. Like the sometimes maligned renegade of the original Surrealist movement, Salvador Dali, Giger was not only blessed with a feverish imagination, he was a master technician who was able to create images of almost photographic realism, which only served to make their content seem all the more disturbing. But here's the odd thing. Giger's work is disturbing, sometimes profoundly so, but it's also strikingly beautiful at one and the same time. Such is his legacy. We mourn the man but he lives on through his art, and if you've never been exposed to it, now is the time to seek out the paintings, the sculptures and the album covers, and maybe even take a trip to Gruyere and enjoy a coffee surrounded by shapes and imagery that place you right inside his remarkable mind.

|