|

What

have the following names got in common: George Romero,

Tobe Hooper, Wes Craven, John Carpenter, William Friedkin,

David Lynch, Jeff Lieberman and Larry Cohen? The answer

will be obvious to any even half-aware genre fan:

they made great American horror movies in the 1970s.

Some of them made horror masterpieces. In the 1970s,

the US was the epicentre of cinematic horror, with

many new young directors using it as a calling card

to demonstrate their talents, rarely letting low budgets

get in the way of creativity. This level of determination

and invention gave birth to films such as The

Texas Chainsaw Massacre, The Hills

Have Eyes, Martin, Dawn

of the Dead, It's Alive!, Blue Sunshine, Halloween and Eraserhead,

all terrific genre films, and all, I would argue,

essentially American. Here the horrors sprang not

from East European folk tales, but from urban terror,

from untrained remnants of the American West, from

the deadening power of consumerism, from the oppressive

industrial landscape, from the drug experimentation

of the 60s, from fears surrounding modern parenthood,

from a decline in faith in organised religion, from

the rise of the urban serial killer. Young, visionary

American directors were drawing on their own experiences,

their own fears and, most crucially, their own culture

and history to explore a particularly American notion

of horror, universal terrors with a specific cultural

identity. These were great days for the genre.

But

as we moved into 80s, the most important definition

of what made an successful film was not vision

of the writer, director or even studio, but how much

it made in its opening weekend. Drive-in screens, once

a ready-made market for low-budget horror film makers

looking to break in to the business, began to lose

their appeal as a movie venue, and the deadly influence

of post-modernism ensured that scaring an audience

became secondary to joking with them about the process

of doing so. It all started soundly enough – John

Landis most effectively blended comedy with horror

with the experiences of young Americans abroad in An American Werewolf in London, and

although Joe Dante named the characters in The

Howling after directors of previous werewolf

movies and peppered the film with ho-ho in-jokes,

he still remembered to serve up a few imaginative

scares and turn in a decent monster movie. But

by the time we got to The Lost Boys (Joel Schumacher 1988), scaring the audience had become

secondary repeatedly winking at them and selling them

the tie-in rock soundtrack album. Shouting "Boo!"

every now and again stood in for genuinely unsettling

or disturbing the viewer, and no would-be horror film

was complete without a tiresome collection of unfunny

wisecracks, usually referencing other and better films.

All of this reached its peak in 1996 with Scream,

a film that made no pretence about its post-modernist

measles, but directed as it was by the erratic but

sporadically brilliant Wes Craven, it also

delivered on its horror credentials.

But it sewed some tiresome seeds, as scary gave way

to funny and scary, and funny and scary gave way to Scary Movie and its ilk. The subtle,

atmospheric, fear-driven horror movie appeared to

have had its day.

Meanwhile

over in Japan, a new breed of film-makers not obsessed

with that opening weekend or with trying to be lamely

funny were drawing on their own horror literature

and cinematic past to create a new breed of genre

film, one that did not spell everything out for the

audience and which thrived as much on atmosphere

as on plot mechanics and sudden scares. In 1997 rising

star Kurosawa Kiyoshi made Kyua (Cure),

a genuinely disturbing study

of a seemingly emotionless young man who acts as a

catalyst for the release of dark thoughts in others.

It did little business beyond its native shores, but

was clearly pointing the way to what was to follow. The

following year, second-time director Nakata Hideo

adapted a short story by Suzuki Koji and made Ringu.

The film was a home-grown phenomenon and went on to

become the most successful horror film in Japanese

history. As it toured the festivals, word started

to get out that a horror film from the East was more

frightening than anything Hollywood had put out in

years, and that it achieved its aim without

showing a single violent act, without spilling a drop

of blood, and without referencing half-a-dozen other

films in the process. Hollywood may not initially

have taken notice, but they were about to be given

reason to.

In

1999, two cinematic events were to have a direct impact

on the floundering American horror genre, waking the

studios from their daze. A pair of enterprising young

film graduates, Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez,

took their knowledge of the immediacy and realism

of cínema vérité and created

a hoax horror documentary in The Blair Witch

Project, and a young first-time feature director

in Hollywood named M. Night Samaylan wrote and directed The Sixth Sense, an effectively low-key

chiller with no jokey referencing, no real violence

and no gore. Both were huge box-office hits, signalling

to Hollywood that actually scaring an audience was

back in vogue, and – crucially – that there was big

money to be made here. Blair Witch in particular was little short of a phenomenon, made

for a paltry $35,000 but grossing almost $30 million in

its opening weekend alone, going on to be the most

profitable horror movie ever made.

For some of the enterprising producers of the 1970s,

such a success would have sent them in search of other new and inventive young film-makers with

imaginative genre projects to sell – after all, look

at the profit margin for such a small outlay. But

in modern-day Hollywood the response was to fund a

series of slapdash and derivative horror tales set

in woodlands or old shacks, none of which came close

to igniting at the box office. Worse still, The

Blair Witch Project became the subject of

a seemingly endless stream of tiresome satires, while

cinematically lazy film students the world

over began making their own universally terrible versions

of the film, driving lecturers and examiners to distraction

and filling them with despair for the next generation

of would-be film-makers. This thankfully short-lived trend was

brought to a resounding close by Myrick and Sánchez

themselves when they produced a sequel, Blair

Witch 2: Book of Shadows, which was so universally

disliked that serious attempts to emulate their original

project ground to a thundering and much appreciated

halt.

Having

really dropped the ball on Blair Witch,

which was made completely outside of the studio system,

there seemed a determination not to do likewise with The Sixth Sense. Initially, the signs

were good – in 2001 Spanish director Alejandro Amenábar,

whose 1997 thriller Abre los ojos (Open Your Eyes) was being remade

as Vanilla Sky, was hired to direct The

Others, another classy, atmospheric chiller

with a well timed twist in its tail, and one

also devoid of the excesses and distractions of the more

teen-targeted American horrors of the 80s and 90s.

It too made money, suggesting that a hunt for new

scripts and exciting new directorial talent to produce

a new wave of intelligent, original horror movies

would soon be under way. Well, no. That would mean

taking risks, and that is

something modern Hollywood is not too fond of doing. Rather than taking

inspiration from its recent successes, it seemed to

regard them as pleasant flukes, strokes of good luck.

What was needed now was another favourable roll of

the dice.

I can't be the only one who believes that Hollywood

functions a lot like the Microsoft, a giant international

corporation that all too often watches others do the

innovating, then repackages the idea as its own and

markets it to death as the finest thing since the

bagel, knowing that the majority of potential customers

also like to play safe and stick with the brand name.*

What Hollywood needed now was the film equivalent

of Apple or Google or Sony to come up with something

that they could rebrand and recycle as original products

for an audience too young, ignorant or lazy to hunt

out the originals. Which, of course, brings us back

to Ringu.

Ten

years earlier, Ringu would probably

have remained a particularly Japanese success, but

a rising interest in Eastern cinema was ensuring that

such films were being seen more widely in the West,

and with the new interest in scary horror over ha-ha horror, Ringu was finding

an audience far beyond its home shores. Thanks in

part to the rise of the internet, something that Myrick

and Sánchez had used so effectively to pre-sell Blair Witch, the strong word-of-mouth

on Ringu was circulating around the

film-watching world and connoisseurs were actively

hunting it out, in cinemas, on video, on imported

DVD.

It's

not hard to imagine the thought process that followed

at Dreamworks. The original is a genuinely scary film

with highly marketable qualities, any film exec could

see that, but it has three main problems for a mainstream

western audience:

- It's a little too low-key in places – no big action bangs;

- It's in the Japanese language and thus has subtitles;

- There are no western characters in the cast and no famous faces to stick on the poster.

After all, The Sixth Sense had Bruce

Willis and The Others starred Nicole Kidman

– what American audience is going to rush out and

see a film starring Matsushima Nanako? The mainstream

audience want the actors to be idealisations of themselves,

and the cast here not only don't look American, they don't

speak the lingo, meaning that there are subtitles

to read, something almost no mainstream audience will tolerate for more than a couple of minutes at a time. Well there's only one answer for any enterprising

American studio, and that's to Microsoft it – buy

the rights and do their own version. They can make

it bigger, more marketable and can push it to a far

larger audience than the original. Behold, The

Ring – it stars Naomi Watts, who is making

a name for herself as an actor and getting in all

the right magazines, it's directed by a man who's

made films the target audience will have heard of

(erm... Mouse Hunt) and, thank the

Lord, it's set in America, has a white faced American

cast and they talk in ENGLISH. It also has a big

advertising campaign, so that that popcorn brigade

can feel secure going to see a film that all of their

friends will have heard of. That this remake never

comes close to matching the creepy effectiveness of

Nakata's original, that it all too often shouts where

the first film whispered, that if feels the need to

explain things that were best left suggested, and

that it completely botches one of the most genuinely

frightening climactic scenes in modern horror is,

of course, beside the point. At least they're not

speaking in foreign tongues.

One

of the key advantages of such a project, of course,

is that the original has not been widely seen within

the remake's demographic. Sure, a fair number of critics

will make a damaging comparison, but not the ones

who feed the popular press, whose enthusiastic gushings

the advertisers will be able to lift compact sound

bites from to stick on the poster, which is the nearest a good

proportion of the potential audience will come to

reading a review. And if someone does point out that

the original was far better, just mention that it

was Japanese and watch the communication shutters

come down. To the mass audience there is only one

version of The Ring, and with Nakata's

film effectively consigned to the art house, the remake

almost manages to pass itself of as an American original,

especially given the sorry state of many of its English

language generic contemporaries. Perhaps the most

ironic aspect of all this is that thanks to the power

of the Hollywood Marketing Machine and Japan's own

fascination with all things American, Dreamworks were

able to profitably sell the remake back to the country

that had spawned and so enthusiastically embraced

the original.

But The Ring made a lot of money, and

ultimately that's what it's all about in La-La Land.

What Hollywood needed now was another product they

could reprocess as their own, especially as there

was so little to shout about with the home-grown product

– Samaylan was heading down a creative cul-de-sac and

reprocessing the same ideas in different skins, Myrick

and Sánchez were still looking for a way to

right the wrongs of Blair Witch 2 (and still are, as it happens), and the surviving

old hands of the 70s were either no longer working

in the horror genre or undergoing creative self-destruction.

But wait a minute, what's that happening across the

Pacific? More horror films? More GOOD horror films?

Aha...

But

something was about to change, something rather odd.

The Remake Machine not only wanted the cash, it wanted

critical respectability. This is an aspect of Hollywood

we more cynical observers often choose to ignore,

but it's actually true. They want the money, sure,

and they want the power of course, but they also want

people to tell them they are wonderful. A LOT of people.

I forget which who it was who first made this observation,

but it has been calculated that if you took the annual

production budget of any major Hollywood studio and

simply stuck it in the bank then you would make far

more money than you would by sinking it into feature

films. Sure, there's the hope that one of those films

might be another Titanic, but if you want to gamble

then the stock market is still a safer bet. No, they

don't want to be seen just as greedy venture capitalists,

they want to be regarded as artistic visionaries.

So every now and then it's good politics to fund a

small movie that stands a good chance of achieving

critical respectability and maybe launch a promising

indie director on a Hollywood career. It doesn't cost

too much and can pay for itself many times over in

good PR and awards. This is the Prestige Project.

And you don't get successful Prestige Projects by

giving them to the director of Mouse Hunt,

no offence intended. Which brings us back, for a second

time, to Ringu.

They

must love Nakata Hideo in Hollywood. Not only did

he give them the raw material for their version of The Ring, but he had made a couple

of other movies that the studio executives clearly

believed could be Microsofted into American products.

First up there was Dark Water (Honogurai

mizu no soko kara 2002), his gripping tale

of motherly love in horror movie clothing, an easy

sell in the US through its association with The

Ring (it was based on a story by the same

author, Suzuki Koji, something that curiously handicapped

the original a little when people went expecting a

retread of Ringu). Although this

had clear potential as a commercial rather than a

prestige project, the studio clearly saw no harm in

attempting to combine the two and hired respected

Brazilian filmmaker Walter Salles, he of Central

Station and The Motorcycle Diaries (whose widespread success and acclaim must have had

the remake producers hugging themselves with joy at

their good fortune) to direct. A cynical view would

see this as an attempt to quieten those critical of

the whole remake process by placing someone of artistic

standing in charge of the project. You may have even

heard the conversation:

"Have

you heard? They doing a remake of Dark Water!

Can you believe it?"

"Yeah,

but Walter Salles is directing it! At least

you know it won't be the usual crap with him

in charge!"

A more generous (and perhaps accurate) view would

see Salles given the project in the hope that he would

bring an outsider's sensibilities to the project and

deliver something more that just a hack job, which

should, well, quieten those critical of the whole

remake process. Oh do you think so?

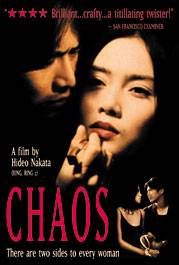

Keen

to eat all things Nakata, his 1999 Chaos,

a brain batteringly

complex tale of kidnapping and deception, was also bought up for an American

remake. But even in English and with American stars,

this is a film that would likely bemuse the multiplex

crowd, at least without a considerable rewrite and

a large dose of dumbing down. Given that the film's

structural complexity, as with Christopher Nolan's Memento and Shane Curruth's Primer,

is what makes it special in the first place, this

would seem to be a pointless exercise. But wait a

minute, the studio has been looking for that ideal

Prestige Project and here it is. All they need now

is the right director, someone who has had a big art-house

hit in the US, and they may have a potential award

winner on their hands. Enter Jonathan Glazer, the

talented young director of Sexy Beast,

the very man to give the story a few coats of class,

tease out some fine performances from a doubtless

respectable cast, and clarify a few of the more obscure

plot points, while just keeping it clever enough to

get it talked about at all the right dinners. That's

prestige taken care of, let's get back to the dosh.

Fortunately

there were other Eastern projects that were soon swallowed

up by the Remake Machine, including the Pang Brother's

unnerving The Eye and Shimizu Takashi's

super-creepy Ju-On: The Grudge, both

of which had already proved hits on their home markets

and developed their own fervent cult followings. In

the case of the latter film the absorption process

was stepped up a gear, with Shimizu invited to helm

the remake himself. Now although this at least keeps

the original filmmaker firmly in the loop, it's no guarantee of continued quality, as anyone who was

creeped out by George Sluizer's 1988 The Vanishing (Spooloos) but gobsmacked by the

tackiness of his 1993 US remake will testify.

All

that aside, the whole process of the Ju-On remake, at least from an artistic viewpoint, always

struck me as peculiar. The man who kicked off the

remake was none other than Sam Raimi, a very talented

director in his own right and a huge fan of the original,

a film he reckoned was one of the scariest he'd seen

in years. He liked it so much, in fact, that he asked

Shimizu to come to America and give it another try.

Now hang on a minute. If the original was as good

as Raimi clearly believed, why exactly did he feel

it needed redoing? Oh, wait a minute, what language

is the original in again? Or more to the point, what

language is it NOT in? Precisely. In Hollywood, a

film is not really a film until it's in English.

Of course, this whole remake issue is one of the many

reasons that some commentators still will not take

film seriously as an art form – can you imagine the

likes of Leonardo da Vinci being commissioned to have

a second bash at the Mona Lisa, maybe tart her up

a bit this time, show a tad more cleavage and even

put her in an Adidas sports shirt? And it tends to

be a one-way process, the global dominance of Hollywood

acting like a creative black hole, sucking in all

it sees and making it part of its whole, then going

supernova and blasting its product back out into the

world on which it feeds.

As

this process of absorption and regurgitation continues,

the American horror film is not only losing its hard

fought-for artistic and generic credibility, but also

the very cultural identity that made the 1970s films

so distinctive and effective. Almost none of the remakes

have any specific cultural resonance, in part because

the stories they're based on originated outside of the USA.** Even when the

industry does try to reclaim the American horror film

as its own, the process is a predictably and depressingly

cannibalistic one, as technically proficient but heartless

remakes are trotted out of its own past generic successes

– Night of the Living Dead, The

Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Dawn of

the Dead, The Fog, House

of Wax, The Amityville Horror, The House on Haunted Hill and The

Hills Have Eyes to name a few, with The

Omen, Piranha, Friday

the 13th and When a Stranger Calls still to come. Elsewhere releases both borrow from

past generic successes and use them as touchstones

for audience recognition, e.g. The Exorcism

of Emily Rose (anything with 'exorcism' in

the title is guaranteed a connection by association

with Friedkin's masterpiece), Saw (borrows from Se7en, promises to

shock and has a title that remembers Tobe Hooper at

his best), The Cave (big blokes take

on dangerous monsters – Aliens anyone?), Cabin Fever (trapped in a cabin in

the woods à la Evil Dead), Final Destination (a series of prophecy-driven

grisly deaths that apes The Omen),

and so on. Even the rare films that have risen above

the mire appear to have done their share of plundering,

with Rob Zombie's The Devil's Rejects lifting from a whole number of the director's favourite

films, and the trailer for the soon to be released

(and, by horror fans, enthusiastically celebrated) Slither playing like Shivers meets Squirm meets Night

of the Creeps.

Despite

hopes to the contrary, it does seem likely that these

films and their inevitable, seemingly endless sequels

are where Hollywood horror is now set to trudge, at

least for the foreseeable future, while the J-horror cycle,

the fuel for a fair number of the remakes, appears

to be caught in a self-destructive spiral of repetition

and sub-standard imitation. On top of that, two of

its key directors now fully absorbed into the Hollywood

Remake Machine – Takashi Shimizu is hard at work on

the next two Grudge sequels, and

Hideo Nakata, having directed the remake of his own Ring sequel, is helming remakes of

both The Eye and Sidney J. Furie's The Entity. Kiyoshi Kurosawa, meanwhile,

has dropped the ball a bit with Doppleganger,

which displays little of the subtextual subtlety of

his previous films, and the Pang Brothers have made

one Eye sequel too many and are no

longer commanding the attention of discerning genre

fans.

As

for the remake of Nakata's Chaos,

the Prestige Project that was more about about the

film than the money? Well it would seem that Jonathan

Glazer, and just about everyone else associated with

the project, has found better things to do.

* Favourite examples include the X-Box,

which would never have happened without the phenomenal

success of the Playstation, the upcoming all-dancing

Zune media player, the result of rival Apple's storming

sales with their iconic iPod, the very vocal determination

to stomp all over Google with MSN Search, and of course

the whole Windows operating system, which was a response

to Apple's designer-friendly graphic user interface

(which itself was heavily influenced by work done at Xerox).

** Curiously, only Shimizu's own remake of The

Grudge includes a specifically cultural element,

built as it is around the experience of Americans

working in Japan, and it is largely these Americans

that fall foul of a curse that was first triggered

by an illicit interracial relationship, casting them,

somewhat unexpectedly, as unwelcome outsiders.

|