“It might be possible to introduce you to somebody

over there…” |

|

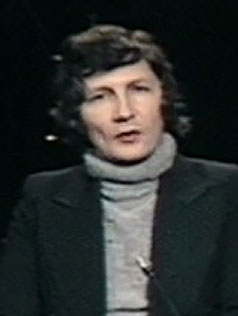

| When an important broadcaster and critic and took an interest in your adolescent career goals, it mattered. It really mattered. To a 17 year old, having the attention and support of the BBC’s Arena Cinema’s host was like a golden ticket to Wonka’s Chocolate factory… Camus plays tribute to mentor Gavin Millar. |

|

| |

|

Everyone has mentors throughout their lives, hugely important souls who find the time to guide and support younger, inexperienced people simply because they want to or are driven to, understanding that those who follow are in need of their guidance. They are the Ordnance Survey maps of the career path you naively set yourself, someone who’s been there before and can point out the contours, snakes and ladders that lie ahead. One of mine, the very first in fact, died on the 20th April 2022 at the age of 84.

Mentors are the all-important tent poles in the roomy marquees of your life, supporting you and providing stability in an area they could claim to have, if not entirely mastered, then certainly succeeded in. To my shame, I’d not been in touch with him for a long time (something more down to a lack of an email address than wilful intent) but the effect this extraordinary man had on my own film career was immeasurable. How we met is inextricably linked with a defining moment in my film-going and filmmaking career. His death was reported on Facebook by his beloved daughter Isobel. The BFI published an obituary on the 29th April 2022…

https://www.bfi.org.uk/news/gavin-millar-obituary

It’s 1978. On the eve of my 17th birthday, I saw a late night preview of a film that was to have a profound effect on me. For more on that experience, please see here and scroll down to the ‘Personal Postscript’. After his rather underwhelming and frankly withering review of Star Wars on the BBC’s Arena Cinema (see here), film critic, author and soon to be film director, Gavin Millar, delivered his verdict on Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Of the sequence and shot that so moved me as a wide eyed 16/17 year old, Gavin said – and I will never forget this – “It was one of the most beautiful things in the cinema.” Well, he might well have just stared into the camera and said “Hey you, drop me a line!” I did just that telling him that I was going to Los Angeles in August 1979, an 18th birthday present from my parents. Gavin said he would introduce me to people who may be able to help. He had no idea that his gentle push led me from my home in South Wales to a Godparent’s spare room in Santa Barbara, on to a Los Angeles motel room to meet with writer/director Joan Tewkesbury and then on to cinematographer William Fraker, all the way to the set of 1941, directed by some guy called Steven Spielberg. I ended this extraordinary experience getting a lift to my motel from the guy who supervised the shoot of the Close Encounters mothership (Larry Robinson). That was the Gavin Millar effect writ large. I was 18. I should have handcuffed myself to Spielberg’s ankle.

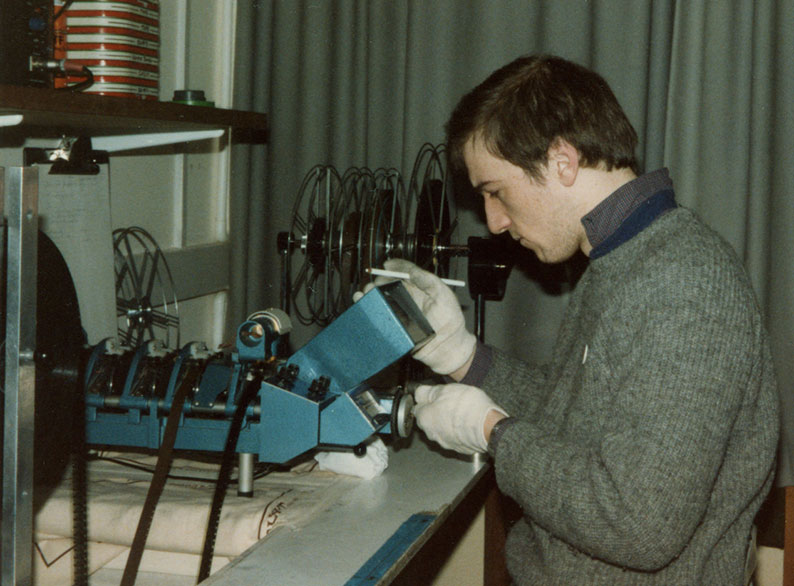

Back in the UK, Gavin continued to support me. I was working as a trainee and then a full assistant film editor at the BBC. Gavin, together with film director Karel Reisz, had authored the definitive book on film editing at the time which was very successful having been translated into a myriad of languages. People moved from assistant to editor at the BBC in those days only if an editor literally keeled over at his/her Acmade (a film and sound sync device that could handle four sound tracks) clutching his/her chest. Alas in those days, it was almost always ‘his’. I was a ridiculously passionate film obsessive (truth be told, I still am) learning my craft and by the time Gavin had moved from film criticism to actual filmmaking, I’d followed his career with profound interest. For those of my age, you may remember a trilogy of TV films made for ITV all written by acclaimed writer Dennis Potter in the early 80s pre-The Singing Detective. Of the three, Cream in my Coffee stood out, a drama about young lovers off for a dirty weekend in the 1930s, a story being told from two time perspectives as the elderly couple revisit the hotel. The hurt and resentment of class antagonism and memories of a wife seeking solace in another’s arms leads to an emotional explosion at the climax. I have only just put two and two together and realised that my fellow BFE (British Film Editors) governor, Derek Bain, edited that TV classic. Lovely job, Derek! Dennis Potter, prepping a feature film to be produced by Rick McCallum (Google the man, George Lucas was his launch pad) enthused about Gavin’s directorial assuredness on this TV film and promoted him to feature film director on his Thorn EMI funded Dreamchild.

One of Gavin’s letters to me showed some concern and yet offered a vastly attractive prospect. He was uneasy that by offering me an unpaid but expenses covered job as his assistant on Dreamchild, he might be torpedoing my BBC career. The BBC said that they would be happy to take me back (forgoing any pension remuneration) as a freelance. So I jumped at the chance and ended up working on Dreamchild as Gavin’s assistant. When you have no clue what you are doing, what you are supposed to be doing and where the limits of your ignorance actually perched, there is a sort of perverse freedom in which to revel. I tossed a frisbee with Fazira Balk shooting Return to Oz at the same time under the direction of ace editor/director Walter Murch. I met up with George Lucas as our producer looked to his own future. And I embarrassed myself spectacularly in front of those in the production office meeting Dennis Potter for the first time…

“So what do you do?” said Potter.

“I’m a hired hand,” said I.

“Aren’t we all,” said Potter.

“Ah, but you get paid,” said I, thereby resolutely terminating my relationship with the greatest dramatic writer the UK had to offer at the time.

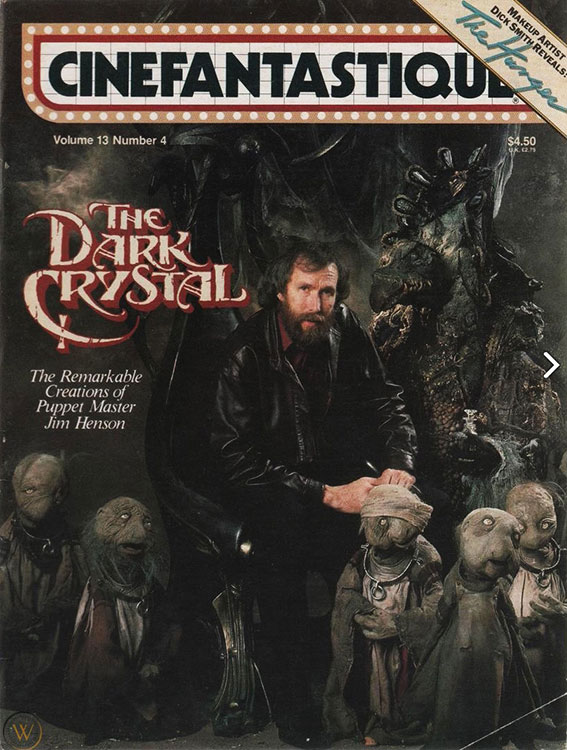

Gavin’s frustrations on Dreamchild were mostly practical. On the astounding set with sparkled cloth covered, electric fan animated, ocean waves and a few ambitious Jim Henson animatronic characters, it took a whole day for Gandhi’s cinematographer, the great Billy Williams, to light the scene after which not a frame of film was exposed. I can’t recall what the actual problems were but for a first time feature director, I could imagine it was frustrating for Gavin. I remember reading a Cinefantastique magazine article on Jim Henson while sitting down watching an animatronic scene being filmed. Henson was on the cover. I will never forget the unmistakable voice of Kermit the Frog from behind me saying “That’s a really nice photo!” Henson was sat just behind me. He was another truly great man taken from us far too early.

Gavin, who fought for the casting of Nigel Hawthorne (Yes, Minister, and Yes, Prime Minister’s Sir Humphrey Appleby) as an influential Oxford Don that took Ian Holm’s Charles Dodgson to task (aka Lewis Carroll), was heartbroken to find Hawthorne’s role rendered superfluous in the final edit. He had to write the actor a letter of profound apology. But there are silver linings if you are prepared to look for them. The most influential US film critic at the time (Pauline Kael) had a real soft spot for Dreamchild…

“Written by Dennis Potter and directed by Gavin Millar, the picture suggests a literate TV show rather than a movie; but it's very enjoyable, and in some scenes it achieves levels of feeling that movies rarely get near. The elderly Alice's Potteresque adventures in the Art Deco New York wonderland wobble in tone, yet the picture is magically smooth, and it's full of felicities. Nothing in Coral Browne's other screen performances suggests the frailty and beauty she brings to her Alice, and Ian Holm's performance is wonderful-sneaky-dirty in its excessiveness, funny and painful at the same moments.”

I couldn’t disagree but if you’ve seen the film, be aware that a sumptuous tracking shot for the emotional punch at the end of the drama could not be achieved with conventional means and so Gavin and his editor Angus Newton had to make do with the closer shot and the wider cut together, the front and tail ends of the planned but ultimately scrapped tracking shot.

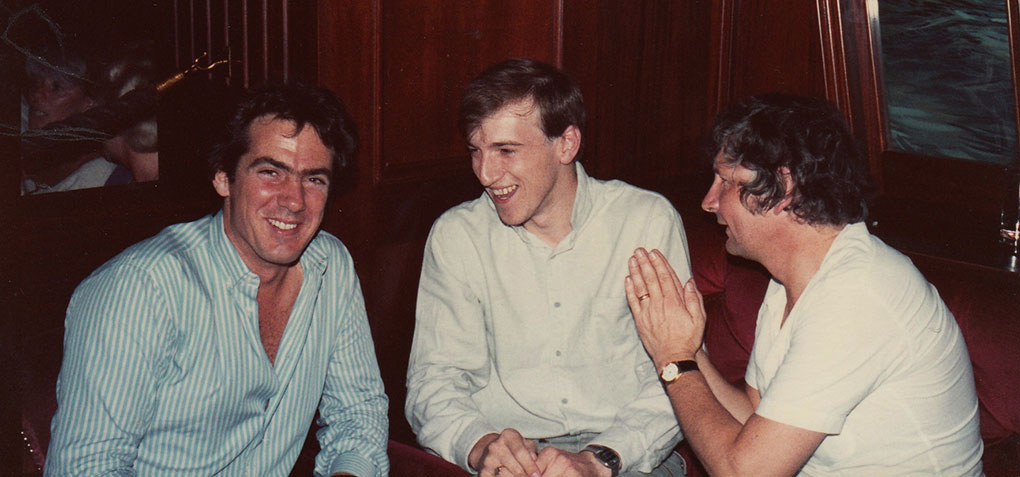

My most vivid memory of Gavin (apart from his ultra-cool Citroen car, a French classic) was his extemporaneous remark upon hearing his producer Rick McCallum tell a joke so crude, he’d be locked up for saying it in 2022. I wish I was joking but Twitter would have a bespoke cross for Rick to nail himself to these days. Despite the offensive joke, the three of us were reduced to stunned hysteria by it, tears pouring out from all six eyes. Rick, I seem to remember, dropped to his knees as he was laughing so hard – at his own joke. The tale involved an orifice, a frog’s demise and the sexual act. After gaining any composure available to him, Gavin simply said “Rick is the only man I know who can disgust himself!”

But above all, Gavin was the first person I met in the film industry who saw potential in this odd teen who so wanted a career moving audiences to tears, joy, laughter and sorrow. To him I owe a massive debt and will do my utmost to pass on the essence of his mentorship to others in my past position now struggling to get a toehold in this vibrantly attractive but wholly frustrating business.

Bless you, Gavin. I remain always in your debt. Thank you.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Director filmography: |

| New Release (TV Series, 22 episodes, 1966-1967) |

| The Impresarios (TV series, 2 episodes, 1967) |

| Release (TV Series documentary, 8 episodes, 1968-1969) |

| Music on 2 (TV Series, 1 episode, 1970) |

| The Eye Hears, the Ear Sees (Documentary, 1970) |

| Review (TV Series documentary, 5 episodes, 1969 - 1972) (director - 6 episodes, 1970 - 1972) |

| Full House (TV Series documentary, 1 episode, 1972) |

| Wessex Tales (TV Mini Series, 1 episode, 1973) |

| Travels with a Donkey (TV Movie documentary, 1978) |

| Cream in My Coffee (TV Movie, 1980) |

| Arena (TV Series documentary, 1 episode: A Pretty British Affair, 1981) |

| Play for Today (TV Series, 2 episodes – Goodbye, 1975 - Intensive Care, 1982) |

| Secrets (1983) |

| Stan's Last Game (TV Movie, 1983) |

| The Weather in the Streets (TV Movie, 1983) |

| Dreamchild (1985) |

| Star Quality: Mr. and Mrs. Edgehill (TV Movie, 1985) |

| Screen Two (TV Series, 2 episodes: Unfair Exchanges, 1984 – The Russian Soldier, 1986) |

| Tidy Endings (TV Movie, 1988) |

| The Most Dangerous Man in the World (1988) |

| Danny the Champion of the World (TV Movie, 1989) |

| A Murder of Quality (TV Movie, 1991) |

| My Friend Walter (TV Movie, 1992) |

| Look at It This Way (TV Mini Series, 3 episodes, 1992) |

| The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles (TV Series, 1 episode, 1993) |

| The Dwelling Place (TV Mini Series, 3 episodes, 1994) |

| Screen One (TV Series, 1 episode, 1994) |

| The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones (TV Series, 1 episode, 1995) |

| Belle Époque (TV Mini Series, 3 episodes, 1995) |

| The Ruth Rendell Mysteries (TV Series, 2 episodes, 1996) |

| The Crow Road (TV Mini Series, 4 episodes, 1996) |

| Sex & Chocolate (TV Movie, 1997) |

| This Could Be the Last Time (TV Movie, 1998) |

| Alan Bennett's Talking Heads 2 (TV Mini Series short, 1 episode – The Outside Dog (1998) |

| Complicity (2000) |

| The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones: Journey of Radiance (Video, segment – Peking, 2000) |

| My Fragile Heart (TV Movie, 2000) |

| The Wonderful World of Disney (TV Series, 1 episode, 2002) |

| Ella and the Mothers (TV Movie, 2002) |

| The Vice (TV Series, 1 episode, 2003) |

| The Last Detective (TV Series, 1 episode, 2004) |

| King of Fridges (TV Movie, 2005) |

| Pickles: The Dog Who Won the World Cup (TV Movie, 2006) |

| Housewife, 49 (TV Movie, 2008) |

| Foyle's War (TV Series, 4 episodes, 2004-2007) |

| Albert Schweitzer (2009) |

|

| article posted |

| 1 May 2022 |

|

|

| See all of Camus' articles and reviews |

|

|