|

Every London Film Festival is a banquet replete with both delectable and inedible morsels, but a single film often rises above the rest to stamp a single indelible image on one’s mind and memory. Anyone who saw that unforgettable moment in Marco Dutra and Juliana Rojas’s Good Manners at the LFF in 2017 will know what I mean. Anyone who saw Vaclav Marhoul’s The Painted Bird at the festival in 2019 will have had a single image branded on their forehead too. Marhoul’s tale of a young Jewish boy’s odyssey through war-ravaged Eastern Europe lays bare the horrors of human depravity with an unflinching intensity that leaves no room for forgetting. But I exaggerate for effect, another film screened at the same festival matched Marhoul stride for stride for the unforgettable image: Agnieszka Holland’s sweeping historic epic Mr Jones.

Based on a true story, it recounts the attempts of an investigative journalist, Gareth Jones, to expose the catastrophic consequences of Stalin’s Five-Year Plan and the genocidal famine in the Soviet Ukraine attendant upon it. In 1933, shortly after interviewing Hitler and raising the alarm about the the Nazis, Jones secured time with Stalin. Once in Moscow, he escaped his minders in search of the truth about Soviet bread shortages and stumbled upon one of the most monstrous and underexamined episodes of 20th century history, the Holodomor.

The term Holodomor is derived from the Ukrainian words for hunger, holodor, and extermination, mor. It perfectly captures the calculated barbarism that lead to the death, by deliberate design and starvation, of several million Ukrainians. And one scene in Holland’s flawed but essential film perfectly captures the horror of that history. Having struggled, starving, through the snow of the Steppes of western Ukraine, Jones careers into a group of emaciated kids who share a welcome stew with him. As the ravenous Welshman devours the gruel, it slowly dawns upon him, and horrified audiences that he is consuming human flesh. Jones’s family insist this didn’t happen. Holland would say it did, if not to him.

Valclav Marhoul put Jerzy Kosínski’s eponymous, nominally autobiographical novel onto the screen in order to tell a dark truth about us all, a truth undiminished by fabrication and fiction. But it has long been known that Kosínski made shit up. Again, we tread the treacherous terrain on which the least palatable realities of human behaviour are revealed beneath the crimson cloak of fiction. I mention Mr Jones for the same reason I recently reviewed The Harder They Fall: to hint at some of the dangerous ramifications of the use of violence as entertainment, and in fiction: the distortions of history that can arise, the dehumanizing tendencies, perhaps the delimiting of gentler human possibilities.

In his essay ‘The Broken Trust of the Image’, the late Dai Vaughan once defended the truth claims of documentary and the indexical status of filmed and still images by referring to the sinister and widespread ‘success of Stalin’s agents in eradicating from the photographic record people who had been eradicated from life’. He continued, ‘The airbrush exercises of the NKVD (were) parasitic upon that very ‘trust’ which is photography’s signature. There is no point in tampering with the facts unless people are going to assume – in spite of all their well-founded suspicions – that you haven’t’. Discussing Godard's Histoire(s) du cinéma, Jacques Rancière notes the master’s conviction that, by allowing itself to become mere mass entertainment and ‘enslaving itself to the story industry’, cinema had betrayed its true vocation: to reveal and communicate, to record and enshrine history.

Dai Vaughan winds his essay down by wondering what might be done to save the documentary, ‘the tap root of cinema, even of those forms most remote from it’. ‘Perhaps nothing’, he says, ‘It is more than possible the cause is already lost, along with that of social progress, with which photography and documentary have throughout their existence been strongly identified – perhaps out of nothing more than a gut feeling that if people were allowed to see freely they would see truly. In spite of constant attempts to accommodate or recruit it, photography has always represented an impediment to the word of authority by virtue of its ultimate appeal to something prior to that word’. ‘Films of this sort’ he concludes, ‘which . . . demand the documentary response as a condition of their coherence, still find their way occasionally on to our screens. We must hope they will continue to do so’.

They do, Dai, and one such film is Sergei Loznitsa’s archive-based documentary Babi Yar: Context. This devastating film reconstructs events leading up to and beyond the massacre, in September 1941, of tens of thousands of Jews in a ravine outside the German occupied city of Kiev. Context is vital to documentary. As cinema increasingly turns in on itself – as if reflecting on its own fragile past while reading the funeral rites of, or reciting the kaddish for people and peoples long gone – it contextualises our collective journey from past to present, from there to here. Period drama and heritage cinema tend to twist the past out of shape with their fanciful tales of Lord and Lady Muck. The histories of kings and queens and stories of cowboys and Indians do so too, largely by omission. We’re left not knowing if we’re coming or going so it’s left to documentary and the likes of Sergei Loznitsa to clear the air and, here, the fog of war. For even, perhaps especially when he draws in propaganda, the photography and cinematography he deploys shine through to insist, ‘This happened, then, to those people, there’.

The renowned Belarus-born Ukrainian has dabbled in both fiction and non-fiction forms throughout a prolific career that began, 30 years ago, at Moscow’s Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography. Loznitsa was clearly taught well at that august ancient institution (which was previously graced by the likes of Eisenstein, Klimov, Parajanov, Pudovkin, Shepitko, Sukorov and Tarkovsky), for he has risen to become one of cinema’s most accomplished talents. He is best known for his meticulously composed archive-based documentaries – films that appropriate, borrow and often restore historic ‘found footage’, thus rescuing images from death or decay and breathing new life into them. Loznitsa covered the contemporary upheavals in Ukraine in Maiden and Donbass, but he returns, time and again, to the Second World War and the Soviet past. In Donbass, a German journalist is accused of Nazi sympathies (‘If you aren’t a fascist, then your grandfather was one’) and a man accused of belonging to a foreign extermination squad is pilloried, publicly humiliated and battered to death. The past haunts Ukraine as it haunts Loznitsa’s films: the Siege of Leningrad in Blockade, the death of Stalin in State Funeral, Stalin’s show-trials in The Trial (’24 frames of lies per second’), Soviet propaganda in Revue, the Yeltsin Coup in The Event, Holocaust tourism in Austerlitz, and, now, most powerfully and unforgettably, the Holocaust again in Babi Yar: Context.

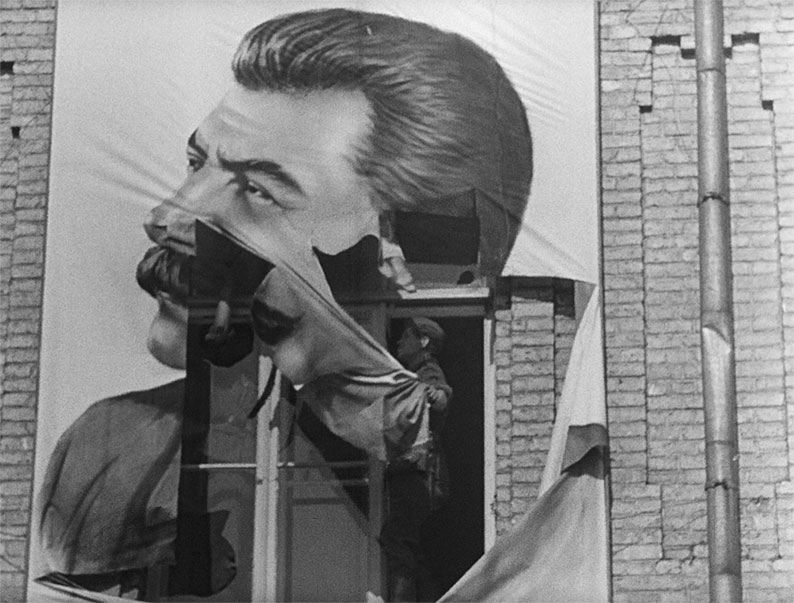

Assembled from public and private archives in Berlin, Baden-Würettemburg, Gescher, Hamburg, Krasnogorsk and Kiev, this extraordinary film crafted from extraordinary footage opens in June 1941. Rendered infinitely more poignant and affecting by a subtle soundscape crafted in Prague’s illustrious Barrandov Studios, the film begins. Images that have lain dormant for decades flicker in into vivid, visceral life. A rumbling, rolling series of mortar explosions disturb the peaceful countryside beyond a bridge over the Dnieper. The Red Army is retreating eastward on all fronts, losing tens of thousands of men per day, and putting its ‘scorched earth’ policy into practise. As billowing smoke fills the air, bewildered peasants go about their daily lives. Here’s a part of Loznitsa’s inevitably incomplete context: Ukrainians caught between a Soviet rock and a Nazi hard place. Burning memories of the Holodomor surface in a warm welcome for the advancing forces of the Wehrmarcht. The invaders are greeted with flowers, giant posters of Stalin are torn down, posters of ‘Hitler the Liberator’ are pasted on walls. Joy, smiles, laughter as release papers are granted to women collecting captive husbands. Adults fight over news and newspapers, children squabble over tiny Swastika flags handed out by German troops.

In Lvov, the Ukrainian militia act upon German orders and gather local Jews at the prison. The corpses of some of those hastily executed by the retreating NKVD are exhumed, laid out, and dusted down with brooms and brushes. The Soviets’ first occupation of Ukraine, from 1939 to 1941, was met with armed resistance by the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists, and many of those who survived such NKVD executions would later enlist in SS units. Columns of captured Soviet troops are herded and corralled by their captors. Aerial footage tracks across desolate, battle-scorched landscapes filled with thousands of abandoned, blackened, burnt-out and buckled vehicles.

In July 1941, the Nazis enter Kiev. Explosions rock the city as stay-behind Soviet units booby trap and destroy the buildings on Khreshchatyk Street that had been commandeered by the Nazi high command. The Lenin Musuem is looted. Boxes of TNT and radios are gleefully prized open. A German cameraman is filmed filming burning ruins. The city is reduced to rubble. Using these ‘Judeo-Bolshevik atrocities’ and accusations of Jewish collaboration as a pretext, the Germans decree that the Jews of Kiev and the surrounding countryside are to assemble with their IDs, money, valuables and warm clothes on 29 September. Over the next three days, the SS-Sonderkommando of Einsatzgruppen extermination units, assisted by the Ukrainian miltia and police, massacre over 30,000 Jews at the Babi Yar ravine. The slaughter there continued throughout the Nazi occupation of Ukraine, rising to over 100,000, and spreads across Ukraine and the Eastern Front to the very gates of Stalingrad itself.

Now, at almost halfway through Loznitsa’s cry for humanity, Babi Yar falls silent. Images gleaned from the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Centre, which supported and sponsored the film, replace moving, equally moving black and white ones. After haunting images of people gathering as commanded, unaware that they are about to enter history and, ultimately, this film, Loznitsa moves to his account of the massacre’s aftermath. Agfacolor photographs of work parties burying the evidence. Of scattered piles of clothing and personal artefacts. Coats, hats, scarves, shoes, blouses, a prosthetic leg, a doll. It’s too horrifying for words. But fitting words will soon arrive. First, footage from a parade – in Stanislau (now Ivano-Frankivsk) in October 1942 – to mark the visit of Governor-General Hans Frank, who would later hang in Nuremberg. Cossacks and Ukrainian nationalists in folk dress are saluted as they pass and a band plays on.

And now the words appear. In 1942, as part of Stalin’s attempts to persuade the Allied powers to open up a second front, the Soviet Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee was formed. Headed by Solomon Mikhoels, Director the celebrated Yiddish Theatre of Moscow, its ranks were swelled by writers of the stature of Ilya Ehrenburg and Vasily Grossman. Together the latter produced the Black Book of Soviet Jewry documenting Nazi atrocities and Jewish resistance (to which Harvard University’s Black Book of Communism was a belated reply). The screen fills, though, with Grossman’s sonorous, hypnotic ode to the life and fate of those the Nazis murdered, his Ukraine without Jews, written between November and December 1943 and rendered in a majestic translation by Polly Zavadivker. It is worth quoting, it seems to me, in its darkly majestic, hypnotic, if hyperbolic entirety.

In Ukraine there are no Jews. Nowhere. Not in Poltava, Khrakov, Kremenchuk, Borispol, not in Lagotin. You will not see the black, tear-filled eyes of a young girl. You will not hear the sorrowful drawling voice of an old woman. You will not glimpse the swarthy face of a hungry child in a single city nor a single one of the hundreds of thousands of shtels. Stillness. Silence. A people have been brutally murdered. Murdered are elderly artisans, well-known masters of trades: tailors, hat makers, housepainters, furriers, bookbinders; murdered are workers, porters, mechanics, electricians, carpenters, bricklayers, locksmiths; murdered are wagon drivers, tractor drivers, chaffeurs, cabinet makers; murdered are millers, bakers, pastry chefs, cooks; murdered are doctors, therapists, dentists, surgeons, gynecologists; murdered are scientists, bacteriologists and biochemists, directors of university clinics, teachers of history, algebra, trigonometry; murdered are teachers, department assistants, Masters and Doctors of various sciences; murdered are engineers, metallurgists, bridge-builders, architects, ship-builders, pavers, agronomists, field-crop growers, land surveyors; murdered are accountants, bookkeepers, store merchants, suppliers, managers, secretaries, night guards; murdered are teachers, dressmakers; murdered are grandmothers who could mend stockings and bake delicious bread, and who could cook chicken soup and make strudel with walnuts and apples; and murdered are grandmothers who didn’t know how to do anything except love their grandchildren; murdered are women who were faithful to their husbands, and murdered are frivolous women; murdered are beautiful young women, serious students and lively schoolgirls; murdered are girls who were unattractive and foolish; murdered are hunchbacks; murdered are singers; murdered are blind people; murdered are deaf and mute people; murdered are violinists and pianists; murdered are three-year-old and two-year-old children; murdered are eighty-year-old elders who had cataracts in the dimmed eyes, cold transparent fingers and quiet rusting voices like parchment; murdered are crying new-borns who were greedily sucking at their mothers’ breasts until their final moments. All are murdered, many hundreds of thousands, millions of Jews in Ukraine. This is not the death of individuals at war who had weapons in their hands and had left behind their homes, families, fields, songs, books, customs and folktales. This is the murder of a people, the murder of homes, entire families, books, faith, the murder of the tree of life; this is the death of roots, and not branches or leaves; it is the murder of a people’s body and soul, the murder of life that toiled for generations to create thousands of intelligent, talented artists and intellectuals. This is the murder of a people’s morals, customs and anecdotes passed from fathers to sons; this is the murder of memories, sad songs and epics of good and bad times; it is the destruction of family homes and burial grounds. This is the death of a people who lived beside Ukrainian people for centuries, labouring, sinning, performing acts of kindness, and dying alongside them on one and the same earth.

The film struggles to tear itself from that astonishing literary core and we fear it may have nothing left to say. It runs out of steam as this review must. Loznitsa, though, rallies and presses gamely on. November 1943. We join a group of American journalists on a fact-finding visit to Babi Yar before cringing at a Soviet propaganda reel filmed on the same spot. The Red Army has retaken Kiev. Again, the familiar columns of captured infantry, this time German; again, the defiant cheeky grin to camera. Again, the bleak wastelands of battle-scarred landscapes filmed from above. Again, the victory parade. Again, the hollow speeches to muted applause. And now, here comes Little Kate: that legendary symbol of Soviet victory on the Eastern Front, that screaming angry embodiment of the push to Berlin and the belly of the beast: the Katyusha rockets.

Next, Loznitsa leads us into the post-war ear and the whispering, hushed hall where we bear witness to the trial of Case Number 1679, in January 1946, ‘On the atrocities committed by the fascist invaders of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic’. We are reminded of the old samizdat dissident joke about the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, often quoted by Loznitsa: ‘There was no Union. It was not Soviet. There were no Republics. It was not Socialist’. An erudite professor attempts to put the massacre of Babi Yar into words, by admitting the task is beyond the human tongue. Only a sculptor of genius, he says, could replicate the animal wail of pain that emanated from one old woman’s larynx. An unruffled German soldier describes his part in the massacre. ‘Six man to guard. Six to shoot . . . They were lined up facing us. And they were shot . . . one machine gun, two submachine guns and rifles’. Asked how many he shot personally, he matter-of-factly replies: ‘In Lemberg, it was 120 people’. ‘In one day?’ ‘No, in total’.

We watch, with bated breath, one of the most famous scenes in the trial, the testimony of a survivor of the massacre, Dina Pronchiva. A consumate actress of Kiev’s Puppet Theatre, she was immortalised in Anatoly Kuznetsov’s celebrated 1966 novel Babi Yar: A Document in the Form of a Novel. Earmarked for execution, forced to undress, she leapt from the lip of the ravine onto a pile of corpses and played dead among them. Barely able to breath she remained frozen as the Nazis shot wounded and dying victims, lay still for hours, even after she had been covered in soil. Asphyxiating, she shrugged off the earth and escaped at nightfall. She was one of just two dozen or so survivors who lived to tell the tale of Babi Yar. We have, indeed grown, fat on peace. We watch transfixed as this immersive film draws to its conclusion, with a card or two still up its sleeve.

After the guilty verdict, the execution. The 29 of January, 1946. Thousands throng a central square in Kiev. Perched in trees, precariously balanced on rooves, crowding together on elevated banks, everyone strains for a better view. Six trucks rev up and pull off. Twelve Germans dangle, twitching in mid-air. A low guttural roar, then, again, silence. The film again seems to have nowhere left to go but again presses on, returning to Babi Yar in more recent times. The local authorities, in their wisdom, have elected to flood the ravine with industrial waste. New housing schemes emerge. Everywhere life moves on. So it goes.

We salute you Sergie Loznitsa. As singular as it is salutary, Babi Yar: Context is immersive, impeccably edited, immeasurably enhanced by a sensitively discerning Barrandov soundtrack, and graced with an elegantly understated musical score that never overpowers its immaculately preserved and elegantly ordered images. A fitting memorial to those who perished in the massacre and the war, this monumental masterpiece of the documentary form recalls, as few films have and do, René Clair’s reaction to a silent film screening: ‘I have seen a cadence!’.

To cruelly paraphrase Czeslaw Milosz’s mighty poem And Yet the Books: ‘And yet the films will be there on our screens, separate beings/That appeared once, still wet/As shining chestnuts under a tree in autumn/And, touched, coddled, began to live/In spite of fires on the horizon, castles blow up/Tribes on the march, planets in motion/’We are,’ they said, even as their frames/Were being torn apart, or a buzzing flame/Licked away their images . . . Yet such films will be there on our screens/Derived from people, but also from radiance, heights’.

|