|

Against the rustling backdrop of autumn’s subtle beauty, the 65th London Film Festival exploded loudly into life last week with the world premiere of Jeymes Samuel’s impatiently anticipated, high-octane Black Western The Harder They Fall. The spectacle is back, the film seemed to say, with a vengeance and a bang. It has to be said, from the outset, that if cinema is to join humanity’s last-ditch dash for sustainability, it won’t do so with big-budget blockbusters like this. $90 million buys the best of special effects, a cast to die for, and huge marketing noise - but it can’ buy you love. An ancient revenge saga interwoven with a proto-modern tale of gang turf wars, The Harder They Fall is brash, brutal and, although significantly based on ‘true stories’ seldom told, otherwise thoroughly conventional. It is also, it must also be said, great fun.

Even though I’ve watched scores of westerns, and even though I’d known what to expect what from this one, I nonetheless found the slaughter in it slightly repellent, without knowing why. Perhaps there was something about the casual callousness with which its characters kill that jarred, perhaps the Black Lives Matter protests had heightened my discomfort at the sight of Black men being gunned down on screen? Perhaps I should’ve shrugged my shoulders and said, as westerns do, ‘Lighten up, let’s not make a song and dance of this, it’s only a matter of life and death after all’. But, no, as I feasted on films during the festival, and intermittently pecked away at this piece, my thoughts returned, time and again, to recurring representations of violence in cinema, culture and society.

They did so a couple of days after I watched The Harder They Fall, as I watched Brian March’s heart-warming paean to the Greenham Common Peace Camp protests, Mothers of the Revolution. And again, today, as I watched Terence Davies’s Benediction and puzzled over a sequence in which soldiers on the Western Front go over the top as if in a castle-rustling Western, to the sound of Stan Jones’ cowboy song ‘Ghost Riders in the Sky’ (yippie-yi-o/yippie-yi-yay). Film festivals are an assault on the senses and cinema jumbles our perceptions of reality (not least due to the disorientating process of stepping between darkness and light), so I decided to group the films discussed below in an attempt to clarify my confused thoughts on westerns and The Harder They Fall.

Although destined to appear on Netflix from November, this expertly executed, if over-hyped entertainment was simultaneously released in cinemas across the UK, on big and vast screens, where it truly belongs.

Those of us who shrugged off sleep for the eight-thirty press preview in the Royal Festival Hall were wide-awake and wide-eyed before the film was even five minutes old. A chillingly vicious cold open sets the tone and foretells the tale. A family of three pray at table before both adults are slaughtered by a pitiless gang led, we later learn, by Rufus Buck (Idris Elba). The sole survivor, Nat Love (Jonathan Majors), full-grown now and forever scarred by that prefatory murder, hunts down his parents’ killers one by one. A priest with a tell-tale tattoo is the film’s next victim. Love guns him down in a further spattering of cold blood . . . and the title has yet to fill the vast screen. In keeping with genre convention, the violence begins immediately, rises incrementally, and climaxes with the inevitable collision of two unchecked forces; here, the gangs of Buck and Love.

In this tale of gang warfare, Love’s Gang is composed of tricksy, jive-talking gunslinger Jim Beckworth (RJ Cyler), lightning-quick boxer-bouncer Cuffee (Daniella Deadwyler), marksman Bill Pickett (Edi Gathegi) and Love interest ‘Stagecoach’ Mary Fields (Zazie Beetz). Buck’s larger, more anonymous gang contains his partner-in-crime ‘Treacherous’ Trudy Smith (Regina King) and his hip right-hand man Cherokee Bill (LaKeith Stanfield). Magnetic as ever, Idris Elba plays it cool and taciturn and doesn’t hog the limelight. Nor does Jonathan Majors, as assured here as on his impressive debut in The Last Black Man in San Francisco, nor even Regina King, fresh from directing One Night in Miami. Even in such company, Stanfield steals the show with effortless ease and photogenic poise, having earlier made his mark in Boot Riley’s wonderful Sorry to Bother You and Shaka King’s vital Judas and the Black Messiah.

Samuel channels Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West and the late, lamented Melvin Van Peebles Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, but Tarantino is clearly his touchstone. Samuel combines the simple-minded, stylised violence of Reservoir Dogs, the historic revisionism of Django Unchained, and the playfulness of Once Upon a Time in . . . Hollywood. Londoner Samuels grew up on westerns and his kitsch kinetic film is saturated with a knowing cinephilia inherited from his mother. My infancy, like his, was shaped by repeats of TV westerns like Alias Smith and Jones, Kung Fu and The High Chapparal but my favourite western back then was, as it remains, John Sturges’s magisterial The Magnificent Seven. I’m still captivated by the way that righteous collective coalesces, individual by individual, as a perfect combination of skills. Samuels might have thought of Sturges’s classic when assembling an extraordinary cast to rival the one Sturges assembled.

Despite the best efforts of its cast, though, The Harder They Fall falls flat. It is enlivened by isolated moment of sly wit (the visual gag of ‘a white town’ created with chalk dust and matt emulsion is delicious), but, surprisingly for a film so playful, it is largely humourless. The plot manages to be, by turns, bare-bones-basic and over-elaborate (few will fathom why Rufus Buck was pardoned by the State, few will be convinced by the film’s ‘yeah, right’ closing reveal). We expect a certain reticence of our Western anti-heroes, but that cast deserved a more nuanced script and more rounded backstories to explore. And even Westerns crave silence, sometimes, that images and landscapes might speak. Samuel’s pulsating soundtrack blends dancehall and dub, hip-hop and reggae, soul and strings, but, even when the volume is occasionally turned down a tad, it jarringly disrupts the stillness of a boundless empty landscape that drove many a sensitive settler and insensitive cowboy mad.

Exuberant and often exhilarating though it is, perfectly placed though its heart is, The Harder They Fall is also deeply troubling. Celebrated instantly for challenging the White Wild West myths fabricated by the likes of Johns Ford and Sturges, it also, paradoxically, valorizes them. Still, a historic corrective that insists ‘These. People. Existed’, includes powerful women in its fictional retelling of actuality, and reinvents a reactionary genre with the aid of a supremely gifted Black cast must, surely, be a good thing, right? Up to a point, Lord Copper! Setting aside the unsustainable mode of its production, Samuel’s kitsch kinetic romp rides into town dragging the hopes of Black Radical and White Liberal audiences behind it, but it makes light of loss of life and is riddled with problematic representations of violence, particularly Black-on-Black violence and the disastrous marriage of masculinity and brute force.

Against those who’d remind us the Wild West was bloody, we might argue that the West needn’t remain so and suggest that the U.S.A would do well to reinvent itself, as Samuel reinvents the western, and take the guns off its streets. We might then invite the film’s admirers to compare The Harder They Fall with, say, Spike Lee’s Chi-Raq (which challenges self-inflicted genocide) and Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight (which bravely resists hackneyed and homogenized representations of Black masculinity). We might also add that while Samuel’s excavation of the hidden histories of Black cowboys and outlaws merits sustained applause, his act of historic excavation and retrieval, paradoxically, does what westerns have always done and erases indigenous peoples from the record. Finally, we might even dispute the overstated case made for the film’s representational originality, perhaps mentioning Perry Henzel’s The Harder They Fall (early on in which its hero watches Sergio Corbucci’s Spaghetti Western Django) before citing pioneering precedents like Mario Van Peebles’ Posse, Charles Haid’s Buffalo Soldiers and Sydney Poitier’s Buck and the Preacher but also by recalling the Jim Crow era race flicks that, for good and ill, were made for Black audiences with Black casts.

As I squirmed in my seat while watching Samuel’s film at Festival Hall, I also recalled the occasion cinema last took me to that hallowed auditorium and treasure of a building. It was November 2016, an unforgettable eight-hour event: a rare screening, with full orchestra, of Abel Gance’s monumental silent classic Napoléon. It is neither here nor there that Gance’s virtuoso split-screen finale received a thunderous standing ovation while the murderous climactic mayhem of The Harder They Fall met with merely muted applause. What struck me, last Wednesday morning, was the contrast between Gance’s radical and Samuel’s conventional stylistic strategies, and the similarities between their claims about the correlation between cinema and history. Samuel and Gance, like D.W. Griffith before them, held they were writing a kind of exact history. After watching Griffith’s racist technical tour de force at the White House, the racist President Woodrow Wilson famously equated it to ‘writing history with lightning’. If The Harder They Fall speaks with forked tongue by bracketing Black history with Black violence, doesn’t its resistance to the whitewashing of history silence all arguments against it?

How each of us answers that question, and questions around the fetishization of gun culture, will depend on our attitudes towards representations of Black masculinity and violence, indeed violence full stop. The debate around Richard Wright’s incendiary novel Native Son is instructive. Wright felt his 1938 short story collection Uncle Tom’s Children too anodyne and palatable; Native Son, his next novel, was anything but: its Black hero, Bigger Thomas, suffocates, decapitates and cremates the daughter of his white employer. He later rapes and kills his Black girlfriend. For the novel’s admirers (including Franz Fannon and many Black Panthers), Thomas’s explosive rage and refusal to repent represented a radical repudiation of enforced timidity, a revelation about the violent propensities engendered by racism, and revenge for centuries of anti-Black violence. It is possible, at a pinch, to identify the hardened protagonists of The Harder They Fall with that tradition of resistance.

Ralph Ellison considered Native Son ‘a near sub-human indictment of White oppression’ designed to shock both Whites and the Black middle-classes out of their apathy. James Baldwin, unsurprisingly, felt Bigger Thomas to be a ‘sub-human’ stereotype and he decried Wright’s suggestion that ‘categorization . . . cannot be transcended’. Samuel and co-writer Boaz Yakin transcend conventional representations of Black masculinity only once, when Nat Love tells a cowed white bank manager, ‘It’s easy to rob a bank, the hard part is to do it without killing’.

When they deftly draw attention to racist power structures by having the Nat Love Gang rob a ‘white bank’ in ‘a white town’, they also unwittingly echo Wright and summon up Bigger Thomas - whose flight through driving snow is often read as a metaphor for a Black man seeking anonymity and cover in whiteness. Samuel’s outlaws are defiantly out in the open but like most Black characters in most westerns, most die in the inevitable hail of bullets. Wright said he’d met men like Bigger Thomas in the Deep South, men whose unbending defiance in the face of oppression blazed ‘at least for a sweet, brief spell’ until they were ‘shot, hanged, maimed, lynched’. Westerns bay for blood so The Harder They Fall could hardly deliver a Black Lives Matter happy ending, but would reconciliation between the warring gangs have been too great a leap of the imagination? Such an ending might have provided a more subtly progressive re-writing of history to set against the reactionary kind the film challenges, if only by its vital assertion that ‘These. People. Existed’.

Whether by happenstance or astute programming, this year’s London Film Festival served up a perfectly timed companion piece to Samuel’s invaluable reclamation project. Alexandre O Phillippe’s The Taking fans out from the westerns of John Ford to range across the manufactured myths that sprang from the arid Monument Valley and seeped deep into western culture. A companion piece, too, to Dee Brown’s landmark counter-history Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, O Phillippe’s riveting film draws its bow and takes aim at the white lies behind the conquest of the West which effectively erased indigenous peoples from the record.

As scintillating as Christian Marclay’s The Clock, as forensically analytical as Rodney Ascher’s Room 237, this exemplary film-about-film sees O Phillippe’s extend his range and reach far beyond his earlier explorations of Antonioni’s L’eclisse, Hitchcock’s Psycho, Lucas’s Star Wars series and Ridley Scott’s Alien franchise. With contained anger and soaring cineliterate eloquence, he takes us on journey from Rossellini’s Germany Year Zero through a history of the Western and the consoling tales White Americans told themselves and the wider world. Illustrated throughout by a range of films featuring Dee Brown’s cast of ‘gold-seekers, gamblers, gunmen, cavalrymen, cowboys, harlots, missionaries, schoolmarms and homesteaders’, The Taking turns the spotlight on those eliminated from, and by that history: those deemed surplus to requirement, ‘the dark menace of the myths’, particularly the Navahoj Nation.

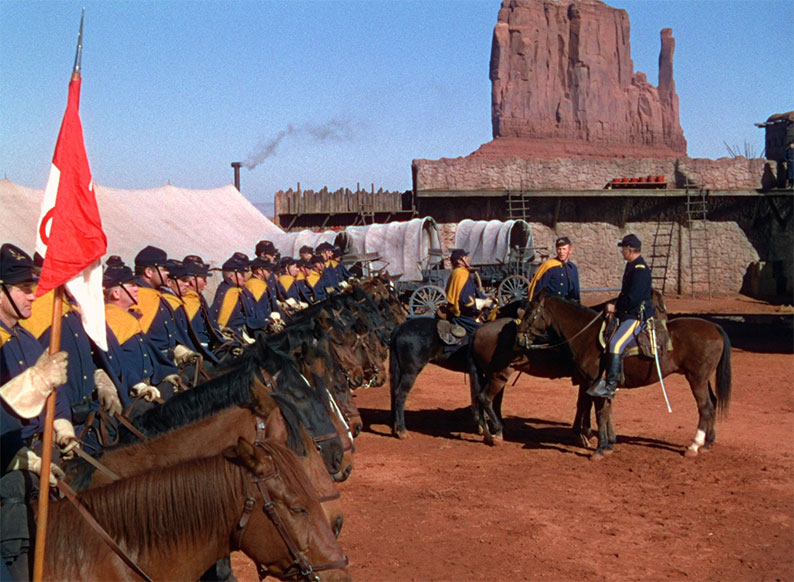

O Phillippe defamiliarizes the deceptive images of the movement west that Westerns repeat: the cattle drives and campfire conversations, the rolling tumbleweed, the circled wagon trains resisting attack, the outnumbered cavalry or pioneers picking off painted braves with lever-action Winchesters, and so on. A series of off-screen voices dissemble this reactionary version of history, of ‘cowboys and Indians’ as goodies and baddies, by focusing on John Ford’s use of the Mitten Buttes of Monument Valley (which Wllla Catha called ‘God’s construction site’) as a fantasy landscape he then claimed was ‘tamed’ by heroic, innocent individualists.

The Taking is more than just an essential didactic intervention, though. It enquires into those elements of universal experience that underpin our visceral responses to mythic landscapes and the reasons they speak so persistently and powerfully to the imagination. At the start of the film, Sergio Leone afficionado Christopher Frayling speaks for many as he recalls the electric charge westerns gave him when he saw them as a boy in bomb-damaged London. Acutely conscious of the impermanence of buildings, he was knocked sideways by the sight of Monument Valley on screen - so seemingly permanent, huge, sacred and silent. Another contributor points to other landscapes, ‘Kubrick used a labyrinth in The Shining, Martin Scorsese used the streets of New York in Taxi Driver, Steven Spielberg used the suburbs in E.T., and John Ford used the monuments in the valley to create a mythological landscape that landed with us visually but meant so much more to us psychologically’

Like the best westerns, this sagely meditative delight is a ceaselessly enthralling exploration of exploration, of the questing human spirit and of the unknown. Just as Christian Marclay does, O Phillipe unerringly finds the perfect image to illustrate each argument being made by each of his erudite experts. In a sequence devoted to restless westward expansion, for instance, he cites the memorable moment in The Magnificent Seven when Val Avery’s Henry asks Yul Brynner’s Chris where he’s from and Brynner nonchalantly flicks his thumb over his shoulder, before Avery asks him where he’s going and Brynner points a firm finger forward. While elaborating on the American optimism implicit in the pioneer ethos, again O Phillippe spots it on a sixpence, with a clip from the cartoon Western An American Tale: Fievel Goes West: James Stewart’s bloodhound Wylie Burp counsels Fievel Mousewitz, ‘Head-up. Eyes steady. Heart open. One day I think you’ll find you’re the hero you’ve been looking for’.

The Taking really is a cinephile’s paradise. All the classic westerns and the many (mainly) men who made them great are packed into this roll of honour (and dishonour): The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, The Magnificent Seven, High Noon, Red River, Rio Bravo, Stagecoach, The Searchers; Aldrich, Ford, Fuller, Hawkes, Ray, Stevens, Sturges; Cooper, Eastwood, Fonda, Lancaster, Mitcham, Peck, Wayne. O Phillippe spreads his net wide and ventures into space, though, so he also quotes from odd bedfellows such as Blade Runner, Solaris, Spellbound, Thelma and Louise, The Third Man, 2001: A Space Odysseyand Woman in the Dunes. O Phillippe covers so much ground and quotes so extensively he always risked overloading the film and overreaching himself. He barely avoids doing so when he veers off to riff on hyperreality and the semiotics of tourism. The Taking is certainly at its coherent best when unpacking the myths that flowed from westerns and circulate still around spurious notions of ‘the winning of the West’.

O Phillippe details the disrespectful ways John Ford played fast and loose with the histories of Native American peoples, and deployed ‘creative geography’, in order to absolve White Americans of their genocidal crimes against indigenous peoples. Most laughably, Ford distorted history by planting spiked saguaro cacti where none existed; more seriously, he perpetuated influential forms of cultural violence which, as one contributor says, fostered ‘the continued cultural appropriation of the West to tell White stories about Brown places’. As Gilles Deleuze crudely put it, ‘If you’re trapped in another’s dream, you’re totally fucked!’

Native American historians Professor Liza Blak and Dr. Jennifer Nez Denetdale, of the Cherokee and Navejo nations respectively, chart the process by which the lands of their forebears were expropriated by capitalists and settlers. Denetdale says, ‘At the same time John Ford is creating this romanticisation of the West, Navajo people and miners were working in Uranium mines. We have the wholesale disappearance of men from our families because they’ve died of the cancers associated with that mining.’ She then introduces us to the divisive figure of John Collier, a patrician reformer in F.D.R.’s administration who developed the ‘Indian New Deal’ that granted a degree of self-determination to indigenous peoples, but who also imposed the controversial Navejo Livestock Reduction programme. Denetdale delivers the chilling punch line of this dispiriting tale: ‘Because of John Collier’s draconian livestock reduction mandate, the Navajo people were left without the means of self-subsistence, so worked for wages for John Ford’s film company’.

O Phillippe leaves the last word to Mark Twain, who provides the coda to The Taking: ‘It’s easier to fool people than to convince them they have been fooled’. Tempted though I am to grant Twain the last word here too, I cannot close without a shout-out to Joshua Altman and Bing Lui, whose intimate observational documentary All These Sons provides a coda to this review by tackling racial stereotyping and highlighting against-all-odds efforts to end the ripple effect of cultures of violence.

Altman and Lui worked together previously on Minding the Gap, an Oscar-and-Emmy-nominated documentary about friendship and fractured familial relations which won a Special Jury award at Sundance. Their latest collaboration follows two committed community activists - Marshall Hatch Jr. of the church-based MAAFA Redemption Project and Billy Moore of the Inner-City Muslim Action Network - as they struggle to break those cycles of violence and moulds of masculinity that blight and curtail so many lives in Chicago’s South and West sides and throughout the USA.

Shot over three years, All These Sons echoes Steve James’s powerful documentary The Interrupters – an earlier, equally urgent and irrefutable argument against gang and gun violence. It comes as no surprise to learn that Altman and Lui were mentored by James, for they share his show-not-tell aesthetic and his commitment to making films with not on people. The avuncular, admirably articulate main protagonists of All These Sons, Hatch and Moore, share a similar ethos: their redemptive work with ‘high-risk’ individuals is based not only on the belief that Black Lives Matter but on the principle that incremental progress is best achieved by working patiently with their charges not on them.

Marshall Hatch works from the basic Christian precept that ‘Thou shalt not kill’ means just that. Surrounded by the victims and perpetrators of gun violence as he is, sanguine though he is, his faith in people is occasionally tested to breaking point. But even when misgivings whisper in his ear, he palms them aside with resolute optimism: ‘The doubt’s trying to convince me that the structural inequalities are too intractable, the self-destruct habits that exist are too deep rooted, but the forces of oppression are unrelenting so the opposite force has to be greater’.

Billy Moore served 20 years for manslaughter and lost his own son to gun violence, so he knows that of which he speaks. He says, simply, ‘If you’re not willing to forgive, don’t expect forgiveness to come your way’. Given the self-loathing his charges absorb from a culture that maligns, misrepresents or ignores them, forgiveness of oneself is a prerequisite for change. Moore himself embodies the very capacities for change, growth and excellence that he so patiently reminds his vulnerable, often traumatised protégés they too possess in abundance.

All These Sons bring us close to some of those Hatch and the MAAFA Redemption Project, Moore and IMAN help to survive and thrive. Among those we meet in the safe spaces provided the groups are Zay Manning, Shamont Slaughter and Charles Woodhouse. Watching these young Black men struggle with their demons and grow, through self-expression and self-improvement, toward self-realisation and self-fulfilment is inspiring. Their stories and unfolding lives are at the heart of the film and, taken together, they offer a heart-wrenching snapshot of the communities, families and neighbourhoods most affected by gang warfare and gun violence. Through them we glimpse some of the names and human faces behind the shocking gun homicide statistics the film quotes.

Charles was shot multiple times when he was just 15 and first imprisoned aged 17. We see him flirting with his girlfriend on a summer’s afternoon but next see him under house arrest, aged 25. Small wonder he’s ‘on edge’. He personifies the tense, twitchy paranoia that pervades his community. The palpable tension of the streets, intensified by a concomitant claustrophobia that claws at those imprisoned in their own communities, permeates the group self-awareness sessions we witness too. It even filters into frame during the chilling moment, during a to-camera interview with Billy Moore, when a cacophonous explosion of gun fire erupts in the background. He barely raises an eyebrow. This might be in Damascus or Kabul but it’s Chicago in ‘times of peace’, a ‘dog eat dog’, ‘kill or be killed’ world in which the urge to revenge is hard to face down.

Zay captures the prevailing mood during one group session when he says, simply, ‘Right now, I’m not too relaxed’. He was shot during the making of the film, soon after he joined IMAN, and we learn he is fighting for his life and ‘bleeding out’ in Cook County Hospital. Thankfully, he survived to rebuild his life. With the support of ConTextos (a transformative writing group that empowers individuals and change attitudes), he was able to commit the story of his painful past to paper and put PTSD behind him. He now works with ConTextos to draw stories from others and create new narratives about Chicago. Sullen Shamont has wrapped himself in barbed wire. ‘My Daddy didn’t know how to love’, he says, and he is clearly struggling with his vulnerabilities. He struggles with the education system, too, and falls back on bad drug habits but, determined to change for his new-born son, he finally returns to the programme.

While these uplifting stories testify to the success of the MAAFA and IMAN programmes, and while Hatch and Moore offer further hope through their sheer indefatigable persistence, Altman and Lui don’t shy from grim socio-political realities of structural racism. They tellingly reveal that Chicago suffers more gun-related murders than Los Angeles and New York combined and that 50 Chicago schools closed in 2013 alone. When Shamont Slaughter and others are taken on a church-run outing to the majority-Black Howard University and Washington D.C., the class divide looms large and the chasm separating their neglected, run-down home communities and that world of power, prestige and wealth yawns wide on the screen. ‘It felt like a movie’, one says of their rare glimpse of the tantalising possibilities beyond their dreams but within their reach.

As the camera tracks down streets of boarded-up houses and schools, we’re left in no doubt that the resources trickling down to the community in Chicago are criminally inadequate. Hatch says, ‘A lot of social service organisations that have been starving for a long time are fighting for the same crumbs’. The funds allocated to crime prevention and the repair of a collapsed social infrastructure are manifestly miniscule next to those poured into policing and police overtime. In one of the more shocking scenes in the film, Altman and Lui film a fraught telephone conversation between the Marshall Hatches Jr. and Sr. and their funding body, which demands a higher proportion of ‘the highest risk’ cases. The pastor says angrily, ‘This is the funding wars. They can leave me out of that dog and pony show. I don’t care to be in no competition for no blood money’.

Although they disavow class struggle, and despite the forces ranged against them, MAAFA and IMAN do their damnedest to tackle the root causes of violence by providing housing, skills training and educational support. Echoes of the community service and consciousness raising work of the Black Panthers, and of the resistance to systematic racism of the wider Civil Rights Movement, reverberate throughout the film. Marshall Hatch says, ‘You can’t move forward until you first go back and get the things you have forgotten. It’s about learning from the past to build a brighter future’. As All These Sons graphically demonstrates, idealism in action continues unabated and groups like these continue to save lives.

The rub of the film, though, is that everything has changed but everything has stayed the same since the Panthers vowed to defend their communities by force of arms and opposed gun restrictions. Guns are the problem now not the solution. And the inbuilt inequalities of capitalism, the Panthers challenged have only multiplied in the interim. As Marshall Hatch says even concerted community action ‘is like a band aid on a bullet wound, because what ultimately needs to change are the conditions that produce shooters in the first place’. Meanwhile, conveyors of decency like himself and Billy Moore press heroically on, providing positive role models for those engulfed in the darkness of contemporary America whom they guide toward brighter lives. In a moving moment that recalls Sam Brown’s Goodbye Mr Chips, Moore says, ‘I lost a son but inherited all these other sons’. His investment in building relationships of trust and mutual respect pays off twice over: for himself and his charges.

‘There is no moving forward without struggle’, Moore says elsewhere in Altman and Lui’s engaging, tender and ultimately optimistic film. A couple of days ago and a couple of days after I’d seen All These Sons, Howard University was occupied by activists from the Live Movement protesting their housing conditions and demanding increased representation. They gathered beneath a banner reading, ‘ENOUGH IS ENOUGH’. A Luta Continua. Lotta Continua. La lutte continue. The struggle continues.

|