|

Since its establishment in 1957, the London Film Festival has consistently justified its claim to be the 'festival of festivals' and 'the people's festival'. By briefing its programmers to find the 'best of the rest' from the international festival circuit, by introducing emerging talent, and by honouring its tradition as a public festival, the London Film Festival affords those who can afford it a unique opportunity to take the temperature of world cinema. Among the many pleasures of attending the London Film Festival down the years is that of watching new directors arrive and develop. As the 56th London Film Festival ends, it is gratifying to report that an unusually high number of successfully realized, substantial first features graced this year's Festival. Its trailer featured a plug for one of its sponsor's, American Express, above whose logo appear the words, 'Realize the Potential'. In this context that slogan is not as meaningless as it first appears. The multitude of precocious directors announcing their arrival this year augurs well for the coming years and it is to hoped that the introduction of competition to the Festival should not take our eyes off films that we consider contenders.

Two directors we will definitely be hearing more of are Chile's Dominga Sotomayor and Scotland's Scott Graham: having delivered sublime debuts of great maturity and depth in Thursday Till Sunday and Shell respectively, both have second features in production. As this year's foreshortened 12-day Festival began, I expressed unease about cinema's continuing reliance on literary sources of inspiration, so it was particularly pleasing to hear that Sotomayor and Graham are at work again already. They are writer-directors capable of crafting daring, distinctive films from their own original scripts and, what's more, of doing so with an admirable economy of style, in response to the inner logic of the stories they tell. Sotomayor and Graham share a restrained, controlled approach to filmmaking that enables situation and character to develop organically and grow naturally, rather than arriving as fait accomplis, enshrined in plots, screenplays, or storyboards that operate as binding contracts. Sotomayor and Graham also share an acute awareness of landscape and the virtues of the long take, an interest in the small moments that mark and shape their observant central characters (both young women), and a view of adolescence as complex and conflicted – all of which pays dividends in these intimate, intense, and intelligent films.

Thursday Till Sunday (De jueves a domingo) follows a petit-bourgeois family foursome's four-day journey from verdant Santiago to the arid North of Chile. Sotomayor's award-winning film opens in the dim light of dawn, with the sleeping figure of its adolescent protagonist, Lucia (13-year old debutant Santi Ahumada), in the foreground. We watch as Lucia is awoken, we watch through her bedroom window as the family car is packed for a nominal camping holiday, and, thereafter, we watch her parents' relationship disintegrate through Lucia's eyes. As the family prepares to depart, Lucia's mother, Ana (Paola Giannini), asks her husband, Fernando (Francisco Pérez-Bannen), if he really wants her to go. It is our first inkling that all is not well between the couple. Early in the journey, Fernando pulls up at the roadside. Lucia and her 7-year brother, Manuel (Emiliano Freifeld), leave food for a man whose wife was killed in a crash and who has lived on the hillside above the road ever since. It is an unsettling episode that immediately insinuates unease.

Later, we learn that Lucia's father has a hidden agenda, to visit a parcel of land inherited from his father, and we have our first hint of his duplicitous nature. Despite his superficially anarchic, democratic sensibilities (he steals fruit, he prefers the battered crate he drives to flashier cars, he lets his kids ride on its roof), Fernando is revealed as an old-fashioned patriarch who prefers his 'son and heir' over his brighter daughter. At one point, Lucia asks to drive and he initially refuses her request. Towards the end of the film, he shares his proprietorial pride in his inherited land with Manuel not Lucia. Such moments are typical of Sotomayor's psychological insight, sure grasp of detail, and tendency to reveal her story incrementally. Her style is less 'show, not tell', more 'suggest, not tell'.

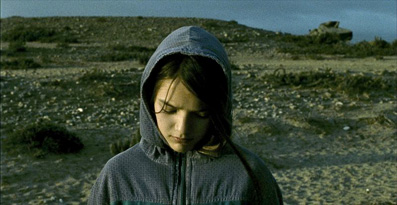

Warnings about plot spoilers are, therefore, unnecessary with this beautiful film, for it is not primarily through a structured plot that Sotomayor weaves her magic, but, rather, through her use of lenses and looks, by deploying image elegantly, and by releasing information sparingly. As the family's northward journey progresses, the tension between Lucia's parents mounts, the couple's sullen silences multiply, and the landscape increasingly reflects the aridity and decay in their relationship. Working closely with her cinematographer Bárbara Álvarez (best known for her work with Lucrecia Martel on La mujer sin cabeza/The Headless Woman), Sotomayor places us in the car with the family, drawing us into claustrophobic intimacy with the characters, and revealing how Lucia reaches an understanding of what is happening to her parents. Sotomayor does this by alternating fixed-position shots within the car, where we are see things most often from Lucia's point of view, with wide-angle shots in open air, where the family and those they meet upon the way are placed against the backdrop of an alienating larger landscape. The rhythm of the journey is reflected in that of the shots, the disintegration of the relationship is reflected in the film's increasingly muted palate. The camera is placed at the service of characterization. We come to identify with Lucia, because, like her, we glimpse her parents from behind: from the backseat, over their shoulders; seeing the sides of their faces, their glances and their avoidance of glances, while eavesdropping their stilted conversations. As slowly as Lucia does, we gradually grasp that we are watching the implosion of a marriage and are riveted throughout until the film reaches its tense, if inevitable climax in an aptly lifeless lunar landscape.

Thursday Till Sunday is, of course, a Latin American road-movie, and the first film that sprang to mind as a useful comparison is Pablo Giorgelli's Las Acacias – a hit at last year's London Film Festival where it was awarded a Sutherland Prize, and a film I reviewed here. When I mention Giorgelli's film, Sotomayor told me: "I haven't seen it yet, but that comparison has been made. A couple of French critics called my film 'the anti-Las Acacias'." She cites among her cinematic influences Antonioni, Roy Andersson, and Cassavetes, despite his fascination with conversation. She says: "Cassavetes without words. The images are more important. What interests me is how to create a complexity that can't be explained in words, to explore how to make emotion visible. I'm always very connected with the camera. What I like about film is logical and complex mise-en-scène. I like some adaptations but I don't think they should be necessary. I'm more interested in why, sometimes, it's not necessary for the camera to move. We really only used five camera positions for the film."

Sotomayor's deft deployment of the camera and of the Chilean landscape as a shadowy presence, and her unsparing if understated depiction of the unspoken dynamics of a family, are complemented by her sensitive handling of a young woman's experience of growing up. The camera ensures that it is Lucia we empathise with. In coaxing a performance of intelligence and subtly from Santi Ahumada, Sotomayor was ably abetted by her own mother, a well-known Chilean actress who helped prepare the child actors for their parts and who cast the boys in the film. Sotomayor herself 'found' Santi Ahumada, while she playing in a swimming pool with her own sister. The Chilean director clearly identifies, as we do, with Lucia, and the mother-daughter relationship is as important to the film's success as the husband-wife one. Although Sotomayor refuses easy categorization as a feminist director, Thursday Till Sunday derives much of its power from her handling of the women and children at its heart.

As Sotomayor and I compared notes on our favourite directors, our conversation turned to two titans of Chilean Cinema, Pablo Larraín and Patricio Guzmán, and to Chile's recent history – aspects of which are brilliantly delineated in Larraín's latest film, No, one of the surefire successes of the Festival, and in Guzmán's latest, Nostaglia for the Light. Sotomayor said: "I grew up in a non-political generation. Now things are happening again, but politics wasn't part of my childhood. It just wasn't discussed at school. But there's something political about my film - its discourse, its way of discussing the world. Everything's very fragmented so the frame can't hold it all. Take the kids: everything's falling apart and the adults are trying to control them. I love the way kids can completely change what the adult world wants from them. I like their craziness and passion and honesty." It is partly Sotomayor's appreciation of that unfettered honesty, and its reflection in the film, that makes Thursday Till Sunday so refreshingly fresh. More than anything, she said, her own childhood is her foremost influence. She lived with her script for several years before it all poured out, partly from own experience: "The film came naturally from observation. I wanted to make the audience slightly uncomfortable and the journey to be without 'big moments' - to be about transitions and the connections. Some of it came from my childhood. I was obsessed with driving. I learned when I was about fourteen. It's part of Lucia's need to be independent and it was part of mine. Lucia is what her mother was 25-years earlier. She is the future." We can be thankful that Sotomayor, and Scott Graham, will be part of cinema's future.

It was no surprise that Mike Leigh was in the audience for the UK Premiere of Graham's debut feature, Shell, during the Festival. There is an element of improvisation about the film that can only have appealed to him. The film clearly appealed to Festival programmer Michael Hayden too. He introduced the film, in glowing terms, as one of his Festival favourites. Like Dominga Sotomayor, Scott Graham is unafraid of probing the darker, deeper currents of human relations and of denying the audience a neat backstory; like her, he displays a mature grasp of landscape and character; and, like her, he drew on his own experience for the film. Shell was developed from Graham's 2007 short of the same name, partly at the Binger Filmlab in Amsterdam; and co-funded by the UK Film Council, Creative Scotland and ZDF-Arte. It is a study in isolation that explores transgressive love, the ties that bind, and, ultimately, another watchful woman's journey to maturity and independence. It is another deft film about growing up, the steady collapse of a relationship, and about seeing: seeing through female eyes, through windows, and through relationships.

Scott Graham has described his film as, "a kind of road movie . . . a roadside movie," For Shell, he constructed a garage near Dundonnell, deep in the Western Highlands, and the film often feels like a windswept Western. The film's heroine, Shell (Chloe Pirrie), lives and works at the garage with her taciturn, damaged father, Pete (Joseph Mawle). As in Thursday Till Sunday, back-story information is released sparingly, allowing us space to think for ourselves. We learn that Shell's mother left them many years earlier, that Shell left school early and was subsequently taught at home by Pete, but little else. Pete's accent betrays his Yorkshire origins, but beyond that we are left to guess as to what lead to his retreat from the world. The claustrophobic intimacy of the family car in Sotomayor's film is replicated, here, by Graham's decision to locate his story exclusively in and around the remote garage. The magnificent mountains that encircle and enfold the garage intensifies the sense that the pair are trapped, and we, to our riveted delight, are trapped with them.

Although Shell's isolated life at the garage is unexciting, she seems content to serve occasional regular customers such as lonely divorcee Hugh (Michael Smiley), and to serve her father's meals. As the story unfolds against a backdrop of daily domesticity and a ruggedly beautiful landscape, it becomes apparent that father and daughter need each other in unusual ways. Shell is always on hand to help Pete when he has one of his occasional epileptic fits and is determined to stand by him, not least because her mother had deserted him. A local likely lad, Adam (Iain de Caestaker) takes a shine to Shell, but she initially keeps him at arm's length, because her father is the unwilling and unwitting focus of her awakening sexual desire. Graham treats that daring incestuous undercurrent, which arises naturally as a logical possibility from his script, discreetly, without descending into prurience. Graham's treatment of landscape is similarly discreet. He worked for the Scottish Forestry Commission while awaiting the green light on his debut, and, although his love of landscape is evident, he doesn't descend into mawkishness. The Highlands are a howling presence in the film, and German cinematographer Yoliswa Gärtig renders it beautifully in a series of wide-angle,fixed-position shots, but, to Shell and Pete, it's just home, a symbol of their self-sufficent isolation.

As the tension in the father-daughter relationship increases, a couple of Edinburgh day-trippers, Robert (Paul Thomas Hickey) and Claire (Kate Dickie, star of Andrea Arnold's Red Road) call at the garage for help. They have collided with a deer, which lies twitching in its death throes on the road. Pete matter-of-factly cuts its throat to end its agony. Pete subsequently skins the deer and its flesh goes in the freezer. Shell later cooks the venison but cannot bring herself to eat it. In a deft touch, she tells Pete: "It would be like eating my own flesh and blood." When the couple return to the garage the following day, to take photographs of their wrecked car for an insurance claim, Claire shows genuine maternal concern for Shell, suggesting something of what has been missing from Shell's life. Claire leaves her a copy of Carson McCuller's novel of alienation and isolation, The Heart is a Lonely Hunter. It is a smart, knowing touch that made me wonder if Shell doesn't contain multiple cinematic allusions, perhaps to Bill Douglas's My Childhood, Graham's favourite film, perhaps to Wim Wenders' Paris Texas, perhaps, even, to Frantisek Vlácil's Marketa Lazarová. It certainly recalls the edgy quasi-documentary style, as well as the tautness and toughness of Perry Ogden's Celtic gem Pavee Lackeen.

Graham's film is enriched by flawless performances from all the actors involved. Pirrie's is yet another astonishingly accomplished debut. She perfectly captures Shell's complexities and contradictions; her self-possession and vulnerability, her naivety and durability; while Mawle delivers an understated but compelling performance as the garrulous but gentle Pete. The supporting cast are equally convincing. Sound Editor Douglas McDougall, too, plays an important part in the film's success. McDougall has previously made telling contributions to Peter Mullan's magnificent Neds and Duane Hopkins' brilliant debut Better Things; his craft and experience is evident in his work on the whispering winds and staccato dialogue that punctuate Shell. It is, though, Scott Graham's assured direction, his vision and his daring that deserves greatest praise. The film's redemptive climax ensures that this occasionally dark film ends with a smile on its face, and there'll be a smile on many a face when Scott Graham returns, the sooner the better, with his second feature. |