| |

“It has to be tough. A policeman's job is only easy in a police state. That's the whole point, Captain – who's the boss, the cop or the law?” |

| |

Mike Vargas to Captain Quinlan in Touch of Evil |

| |

“…on Touch of Evil Welles was at the top of his bent. He was 42 years old, in top form and everything he did with this film was virtuoso. Virtuoso directing, virtuoso camerawork, virtuoso editing. He was right on the money in everything he was doing.” |

| |

Rick Schmidlin, producer of the restoration of Touch of Evil1 |

For cineastes, it’s unquestionably one of the most famous opening sequences in cinema history, so much so that any time you see or hear Orson Welles’ 1958 late-noir masterpiece, Touch of Evil being discussed, you can bet your bottom dollar that this three-minute, 20-second shot will be part of the conversation. Even today, with the motion-controlled boom arms and CG-assist that filmmakers have their disposal, it has the power to drop jaws, in no small part because we know that Welles and his talented cinematographer Russell Metty executed this insanely complex shot without the aid of any such technology. On receiving this new UHD release from Masters of Cinema, I ran the sequence for my partner, who’d never seen or heard of the film before. Her response was an open-mouthed, “How?” When it comes to the techniques used, I was able to give her an idea, but that’s only a small part of the story. Never mind the concentration and timing required of the actors and the plethora of bit-part players (one of whom kept famously fluffing his line, requiring everything and everybody to return to their starting positions to go again) and those marshalling the action as the camera rises and falls as it drifts through the Mexican border town of Los Robles, spare a thought for those charged with keeping the camera moving, with raising and lowering the crane on cue, and the oft-undervalued individual charged with keeping the image in focus as it drifts from close-up to sweeping wide shot and a varying range of carefully composed shots in-between. I’ll have more to say about how hard that particular individual’s job must have been on this film a little later.

Elaborate and indulgent though this all may sound on paper – at least to anyone who has never actually seen it – as a piece of audio-visual storytelling it’s both artistically masterful and narratively economic, an undervalued aspect that hits its peak as Mike Vargas (Charlton Heston) and his wife Susan (Janet Leigh) approach the American border. What unfolds is a short but beautifully concise dialogue exchange that tells us a lot about Vargas with deceptively little. His fame is established by the fact that he is instantly recognised by the two border guards; his popularity by their cheerfully friendliness towards him; his profession by the question, “Hot on the trail of another dope ring?”; that he’s off-duty by his laughing response, “Hot of the trail of a chocolate soda for my wife!”; the fact that he and Susan have only recently married by the first border guard’s incredulous cry of, “Your wife?”; that they may be on their honeymoon by Susan’s response, “Barely a bride, officer.” It’s even signalled early on that Vargas is a Mexican national when he and Susan are asked if they’re American citizens and Susan says with a subtle emphasis on leading pronoun, “I am, yes.” And we absorb all of that in just 20 engaging seconds of screen time. The brief exchange that follows reveals that Vargas has recently cracked a big case involving a drug kingpin named Grandi, and that other members of the large Grandi family are still at large, a snippet of casual conversation that will soon prove crucial to what unfolds. Meanwhile, the driver of the car in which we saw a bomb planted at the start of the shot waits impatiently to be let through, while his female companion complains distractedly about “this ticking noise in my head.” Seconds later, the shot ends with Vargas and Sarah’s first kiss on American soil, and an off-screen explosion that cuts brilliantly to the flaming car in mid-fall from the devastating effects of the bomb, the camera catching it as you might if you spun your head in that direction immediately after hearing it explode.

Despite killing a local bigwig named Rudy Linnekar, the bombing ultimately proves to be a MacGuffin to bring morally upright detective Vargas into contact and eventual conflict with corrupt local police Captain Hank Quinlan (Orson Welles), which proves to be the film’s true raison d’être. The very moment that the burning car hits the ground, Vargas has a mode switch from loving husband to investigative cop, an instinctive prioritising of the professional over the personal that is encapsulated by the brief exchange between him and Sarah that follows a few seconds later. “This could be very bad for us,” Vargas says, looking around at the unfolding chaos while holding Susan’s hand protectively. “For us?” Susan asks, curious and concerned. “For Mexico I mean,” Vargas clarifies, then sending her off to the hotel so that he can do a little professional digging.

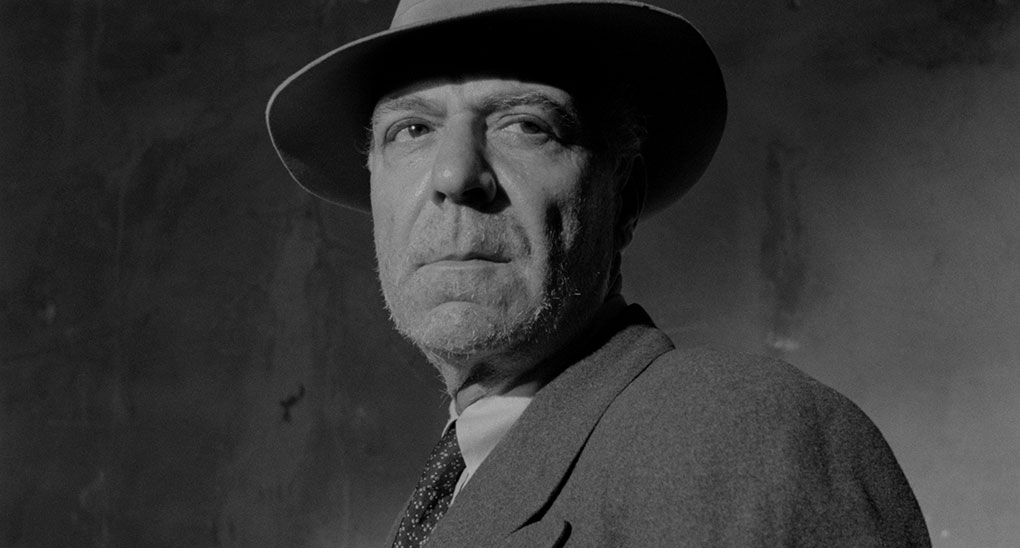

It's then that we’re treated to what remains one of my favourite character introductions in cinema history. As Vargas converses with representatives of the local police and legal hierarchy, a car rolls up and District Attorney Adair (Ray Collins) says, “Well, here comes Hank at last,” then turns to Vargas and asks, “You've heard of Hank Quinlan, our local police celebrity?” “I'd like to meet him,” replies Vargas with an optimistic smile, to which the Coroner (an uncredited Joseph Cotton) growls sardonically, “That’s what you think.” Cut to the now stationary car as the driver’s door pops open and the scowling, overweight, dishevelled, sweaty, and cigar-smoking Captain Hank Quinlan (Orson Welles) spills out of the vehicle, his considerable bulk emphasised and even exaggerated by the expressive upward gaze of Metty’s camera. Having visually drawn an expressive picture of his character, Welles then expands on this with Quinlan’s first conversation with his colleagues, where the use of overlapping dialogue and amusing asides (“Well, what do you know? The D.A… in a monkey suit” he says with a short laugh to the formally dressed district attorney) immediately establishes him as an oddly likeable figure of interest. Amusement at his banter quickly fades when his contempt at the very idea of Vargas getting involved in the case proves to be not because he regards him as an unwelcome outsider, because he’s Mexican, the first indication of Quinlan’s deeply ingrained racism.

Although also a strength, Vargas’s integrity and dedication to his work quickly proves to also be his Achilles heel, as it leaves him open to attack through his new wife. Even before she reaches the hotel to which she has been effectively sent, Susan is approached by a shifty-looking leather-jacketed Mexican youth (Valentin de Vargas) that she casually insults by calling him ‘Pancho’. He hands her a note requesting that she follow him so that she can collect something important for her husband, which lands her in the company of toupee-wearing Joe Grandi, the uncle of the shifty youth and the brother of the drug lord that Vargas is currently prosecuting. He attempts to pressurise Susan into persuading Vargas to drop the case, but she’s having none of it and stands up defiantly to his every threat. “You’ve been seeing too many gangster movies!” she tells him sternly after taking a swipe at a phallic cigar that Grandi wedges in his mouth before approaching her. He eventually allows her to leave, but the intimidation doesn’t end there. When changing in her hotel room, Susan is suddenly lit up by a torch being shone by Pancho (sorry, but that’s also how he’s listed in the credits) from a darkened room in the building opposite. Things move up a notch when another of Grandi’s nephews, a young hothead named Risto (Lalo Rios), throws a bottle of acid at Vargas, then flees after narrowly missing his target, only to be then grabbed by Grandi and balled out for potentially making things worse for his brother. It’s clear even at this point that the way Grandi intends to get at Vargas is through Susan, but what exactly does he have in mind? Oh, you wait…

That Vargas and Quinlan will eventually clash is signalled early by the conflict between their differing approaches to investigation, with Vargas relying on logic and evidence and Quinlan favouring intuition, claiming to know the bomb was made from dynamite because of a twinge in his game leg. Initially, this paints Quinlan more as lazy than corrupt, but this all changes in a centrepiece scene whose technical execution is in some ways every bit as complex as the celebrated opening. Captured in a single six-minute, 23-second shot that continuously reframes with the movement of the characters, and even drifts smoothly between rooms, it observes Quinlan and his men as they question the bomb victim’s daughter, Marcia Linnekar (Joanna Moore) and interrogate Maleno Sanchez (Victor Millan), a young Mexican man that she shares an apartment with. After Marcia is led away by her attorney, the camera follows Vargas through the bedroom and into an en-suite bathroom to wash up, where he accidentally knocks over an empty shoe box whilst reaching for a towel, leaving Quinlan to do exactly what Sanchez was afraid of and attempt to extract a confession through the use of physical violence. Vargas stays true to his word and doesn’t intervene, but suggests to assistant district attorney Al Schwartz (Mort Mills) that the boy might be innocent, and even offers up a theory of his own about who might have planted the bomb. Vargas then nips out to make a phone call to his wife, and when he returns, Hank’s loyal assistant, Sergeant Pete Menzies (Joseph Calleia) claims to have found two sticks of incriminating dynamite in the shoe box that Vargas knocked over earlier. Vargas confronts Quinlan about this deception, and in the argument that follows directly accuses him of framing Sanchez. It’s here that the battle lines between the two men are effectively drawn. But it’s when Vargas departs that the true extent of Quinlan’s corruption and abuse of power become evident. After Schwartz makes it clear that he has to take Vargas’s claim seriously, and Menzies reminds his boss that Vargas is a figure of some standing, Quinlan is persuaded by the sleazily manipulative Grandi that they now have a common enemy, and while Vargas starts looking into Quinlan’s past cases, Quinlan and Grandi start making their plans against him.

By this point, Sarah has been driven by Menzies to an alternative motel the sort of isolated spot in the desert that no-one with any sense would choose to build such an establishment. If that alone wasn’t enough to give it a Psycho vibe, blonde-haired Janet Leigh is the motel’s sole guest, and the only one staffing the place is the unnamed night manager played by a young Dennis Weaver, who appears to have been given free reign by Welles to be as spectacularly – I would almost say cartoonishly – nervously twitchy as he fancied. His idea of being helpful is to turn on a radio that pipes loud hillbilly music into every cabin, making sleep for the by-now exhausted Sarah nigh-on impossible. And that’s before Pancho rolls up at the motel office with a colourful collection of young tearaways who would not be out of place as supporting characters in a David Lynch movie – it’s easy to imagine them as part of Frank Booth’s gang in Blue Velvet (1986), while the desert motel location prefigures the one in which Bobby Peru intimidates Lula in Wild at Heart (1990). They’re led by uncredited Mercedes McCambridge, who would later provide Raegan’s demon voice in William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973) and who still scares the living crap out of me here simply by opening the door to Sarah’s cabin and walking slowly in.2 Every second that Sarah spends at this remotely located motel makes for uncomfortable viewing, but with the arrival of the gang the discomfort level is really ratcheted up, and peaks with an assault that is later suggested (but in no way confirmed) to not be all it initially seems and that still has me squirming in my seat every time I watch the film.

Any suggestion that Quinlan will be a one-note villain is dispelled by an early scene that provides a teasing peak into his past and the man he presumably once was. When he and his associates take an unofficial trip over the border into El Robles, he suddenly recognises a pianola tune coming from a nearby building. As he enters, he comes face-to-face with world-weary gypsy fortune teller Tanya (Marlene Dietrich), whom he pauses to gaze at with obvious affection, clearly expecting a similar response from her. He doesn’t get it. The bored-looking Tanya initially mistakes him for a customer, and when he identifies himself by name, she gives a mild look of surprise and admits in an almost offhand manner that she didn’t recognise him. “You should lay off those candy bars,” she tells Quinlan as he takes another bite from his seemingly never-ending supply. “It’s either the candy bars or the hooch,” he responds ruefully, then adds, “I must say, I wish it was your chilli I was getting fat on.” We’re left to speculate on the nature of their former friendship, but it’s clearly not one Tanya is keen to rekindle. “You’re a mess, honey,” she tells him, to which he responds with an almost sheepishly accepting, “Yeah…” Quinlan’s words also subtly hint at a possible former alcoholism, which is later confirmed when the scheming Grandi effectively pushes him off the wagon. Again, we can only speculate on what caused him to initially turn to drink – was it a breakdown of a former relationship with Tanya, or self-medication for the pain following the bullet he took for Menzies that left him with a permanent limp? Later, when he pays a second visit to Tanya, the conversation is more downbeat, as he drunkenly spreads the tarot cards on the table and demands that she read his future, and she replies with a tellingly apprehensive flicker of her eyes, “You haven’t got any… Your future is all used up.”

Every performance in the film is remarkable in its own way. The very white Charlton Heston may have been browned-up to play Mexican Ramon Miguel ‘Mike’ Vargas, but it’s worth remembering that this would not unusual for the time, and he commits completely to a character that, despite the moral stand he takes against Quinlan, is actually not that likeable. As for Quinlan, he has to be one of Welles’ most extraordinary creations, a colourful grotesque whose bloated body and increasingly unkempt appearance are symbolic of his long-standing moral and ethical corruption. He’s certainly an embodiment of the notion that a good villain is always going to be more interesting than even a decent hero, although the lines between the two subtly blurred here, with the suggestion that Quinlan’s disreputable methods actually achieve results, while Vargas is so wrapped up in his work that he becomes unknowingly culpable for the nightmare that is inflicted on his new bride. Janet Leigh has probably the toughest job here, targeted as she is to be a victim from an early stage, but showing a strength of character and a refusal to be intimidated by Grandi that not only kicks against the norm for such a role, but makes her easy to engage with and feel for when events take a darker turn. Marlene Dietrich may be playing a small supporting role – presumably as a favour to an old friend – but boy does she make an impression, economically expressing Tanya’s weariness at the world in general with a single, unblinking stare and a tired exhalation of cigar smoke. Joseph Calleia initially amuses in his overeager fawning over Quinlan as his trusted deputy, Pete Menzies, but really comes into his own after Quinlan takes his plan to ruin Vargas a moral step too far, and from this point on he quietly steals every scene he is in. I’ll also give a shout for Mort Mills, whose consistently grounded performance as Al Schwartz makes him for me the most believable character in the film, one I had no trouble swallowing that Vargas would instinctively trust. Even Dennis Weaver’s larger-than-life twitchiness is put to effective use when nervously confronted by an impatient Vargas, or when surrounded by leather-jacketed gang members, as he protectively clutches his bag and flask, looks around nervously for a safe exit, and starts subconsciously matching the rhythmic bouncing movements of one amphetamine-fuelled goon.

It's been well chronicled that the original script was transformed by Welles the writer and then layered still further by Welles the director to shape a basically pulp story in the richly textured film that it became. Taking advantage of the decision to shoot exclusively on location in California’s Venice neighbourhood, he and cinematographer Russell Metty repeatedly break with the convention of matching the eyeline of the actors to look up at them instead, almost from the viewpoint of a small child. This not only emphasises Quinlan’s bulk and the menace of Grandi’s goons, it subconsciously discomforts by presenting generically familiar action from an unfamiliar viewpoint. Welles intercuts this with an expressive use of facial close-ups, a series of smoothly executed dolly shots, and the sort of carefully choreographed multi-character blocking and use of deep focus that have been Welles’s signatures since Citizen Kane (that the focus on some shots is not quite on point is something I touch on further in the Sound and Vision section below). Also memorable is a striking shot of Vargas driving down a long straight road through the town, conversing with Schwartz as he does so and recorded by a camera bolted to the bonnet of his car. A common-enough shot this may sound, but even over half a century later you’re unlikely to have seen one that looks or feels quite like this.

Like my fellow reviewer Camus, who covered Eureka’s previous two-disc Blu-ray release of the film (which you can read here), I can’t remember precisely when I first saw Touch of Evil, but am fairly certain it was in the early to mid-1980s and that it was the theatrical version that so infuriated Welles. Like my fellow scribe, I recall being left a little confused by some of the plot points, and watching it for the first time on a TV whose screen would now have to grow a bit to be considered small was far from ideal. Yet this all paled into insignificance when the film had so much to offer this unprepared viewer, in the performances, the execution, the layering of the subtext, the simultaneously artificial and yet very real sense of place, the tangible air of menace, the colourful characterisation, and the gloriously seductive oddness of the work. I loved every bit of it, but seeing a second time back then meant waiting for another TV screening and slamming a VHS tape in my recorder to preserve it and rewatch it at my leisure. Then, in 1998, news of the reconstructed version based on Welles’ 58-page memo to Vice-President in charge of production at Universal-International emerged, and I couldn’t have been more excited. When I finally got to see it, I was struck by how much more clearly the story seemed to unfold. Sure, I was a lot older and had seen thousands more movies by this point, but I wasn’t the only one for whom this was something of an awakening. It’s just that…

So here’s the thing. When you spend years loving a film and a new version appears, your reaction to it is inevitably going to be mixed. Yes, it may improve on elements that were originally shaky or unclear, expand on aspects of the story or provide more insight into characters and plot motivation, but this is often offset by the simple fact that this is no longer the movie that you first fell for and have come to know so well. Sometimes these changes can shift the balance of the film in a way that doesn’t work for you as well as the original did, while at others just a single change will have you harking for how it once was. It’s this attachment to the original that ensures I’ll take the original cut of The Warriors and Apocalypse Now any day over the later redux editions (I’ve made my case for both past reviews), while James Cameron’s extended cuts of Aliens and The Abyss both work a treat for me. It’s a purely personal thing, so feel free to disagree.

When it came to Touch of Evil, I was knocked out by the Reconstructed version, but with one small but – for me, at least – significant caveat, and that was the presentation of that celebrated opening shot. In the version that I had known and become so attached to, it played under the main titles to a gloriously jazzy score by Henri Mancini, which I had always regarded as a sublime marriage of music and imagery. Now the music was gone, the title graphics were gone, and after so many years viewing in its admittedly studio-cut original form – and remember, I probably watched that opening shot even more frequently than the film itself – I found myself mourning the loss of those elements and even thinking that the shot now felt somehow a little empty. Indeed, I remember being overjoyed when I discovered that the French language track of the DVD release of this version still had the Mancini score in place. But that’s now all changed. Years later, I’ve come to love that opening as it was meant to be seen, shorn of what I now regard as distracting title graphics and swept along by the chatter of the townspeople and the pools of diegetic music emanating from bars and the radios of open-top cars. Now everything in the film clicks, and I’ll freely admit that the restoration has transformed a great work of cinema into a truly sublime one. It may not be Welles’s greatest or most important film – Citizen Kane was just too innovative, too beautifully told and performed, too complex and layered, and too artistically brilliant a work to be knocked off that pedestal in a hurry – but I have no problem admitting that for all sorts of personal reasons, when it comes to Orson Welles movies, Touch of Evil has always been, and will likely always remain, my favourite.

In common with the previous Blu-ray release, three different versions of the film have been included in this set, spread across two UHD discs – the 95 minute Theatrical Version, the longer 109 minute Preview Version, and the 110 minute 1998 Reconstruction, which now has to now be considered the definitive cut.

Before I get to the specifics of this transfer, there are a couple of points that I need to address, the first of which is highlighted by the higher definition of the 4K transfer on this disc. Put simply, there are shots here, often night-time exteriors, where the focus is visibly off, sometimes by just a little, just occasionally by more. Given that material from several sources was used for the restoration, it’s highly possible – probable even – that some of the reconstructed footage was not of quite the same quality as the more pristine imagery here, and thus looks a little softer when positioned next to a shot sourced from a higher quality original. Yet there are also shots in which a character foregrounded in frame appears soft, but the background looks sharp. It’s worth remembering that the film was shot on location, often outside at night with the aperture wide and a resulting narrow depth-of-field, and without the focus-assist technology we now have at our disposal – this was tape measures to focus and actors having to hit their marks in the dark on a film with a fast shooting schedule and an above-average number of setups per day. Occasionally, I wondered if this was an artistic decision, as in the shot at 13:37 where Quinlan’s four associates turn to question Vargas to discover he’s walked off, and despite almost filling the frame, the focus is soft on them but noticeably sharper on the neon striptease club signs in the background – a sly ploy to draw our attention to them, perhaps? When it comes to the shot of Quinlan and Menzies walking across a bridge at 1:40:54, when both men are blurry and the steel crane in the background is pin-sharp, however, I have trouble seeing this as anything but a casualty of working at speed in low light conditions. For me, none of this impacts the film in the slightest, but is obviously relevant to a 4K UHD transfer and should not be the material by which its quality is judged.

The second point is primarily for those who enjoyed the option offered by the previous Blu-ray release of being able to view the film in either the 1.37:1 aspect ratio in which it was shot or the 1.85:1 ratio in which it was usually projected, as here all three cuts of the film are available in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio only. As the booklet that came with the earlier release made clear (more on this below), at the time the jury was out on which of the two aspect ratios was the correct one, and it would thus be interesting to know why 1.85:1 has been selected as the definitive aspect ratio since. Thus, if you prefer to watch the film in the Academy ratio, you may have to stick to the Blu-ray. Except…

Being in a position to directly compare the 2011 Blu-ray with this new UHD side-by-side on the same 4K OLED TV screen, I looked for shots that would showcase the image quality at its best, and the first one I chose was a close-up of Quinlan as he looks affectionately at Tanya when he visits her establishment. Twelve years ago (has it really been that long?), Camus rightly praised the transfer on the previous Blu-ray, but using the above detailed shot as a reference image, this new UHD transfer genuinely leaves the Blu-ray standing. The stubble on Quinlan’s face that is indistinct on the Blu-ray is so clearly rendered here that you could almost count the individual hairs, and the detail on the ornate lampshade behind his left shoulder is considerably more distinct, despite not even being in Quinlan’s plane of focus. Obviously, shots that look a little soft on the Blu-ray are not going to be any sharper here, and as noted above, they tend to be more visible because of the increased sharpness of the material that surrounds them. Crucially, it’s not just the resolution bump that makes this transfer superior, as the Dolby Vision HDR allows for a far more expansive and dynamic contrast range, deepening the shadows without sacrificing picture detail and bringing out the subtleties of the lighting in a way that makes characters, objects and locations feel more three-dimensional. Switch back to the Blu-ray after watching its more richly rendered equivalent scene on this UHD and it feels almost flatly rendered by comparison. A fine film grain just adds to the cinematic look of the transfer here.

[A quick note – although the screen grabs included here have been taken from the UHD, they lack the HDR processing that really brings the image to life when played on a compatible screen, so shouldn’t be used as an accurate barometer of the image quality of the transfers.]

When it comes to dust spots and former damage and wear, the Theatrical cut is almost completely clean, and while there are some minor scratches and one brief bit of sparkle visible on a couple of shots in the Reconstructed version, they are not distracting, and in many cases likely only visible at all due to the higher resolution of this 4K transfer. Intriguingly, the shot in which Vargas confronts the motel night manager, which includes more footage at its front end in the Preview and Reconstructed versions, has some fine but visible scratches on the Reconstructed version that are not present on the same shot in the Preview cut, though the image is far more stable in the Reconstruction (watch how the ceiling of the cabin seems to warp and wobble in the Preview version) and so is clearly preferable.

The DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 mono soundtrack also represents a serious upgrade on the DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 mono track on the Blu-ray, being considerably louder and boasting an improved clarity and tonal and dynamic range. Again, there are no traces of background hiss, damage or wear. For a film of this vintage, it really sounds good.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired have been provided for all three cuts of the film.

The following special features have been carried over from Eureka’s previous Blu-ray release, and are reviewed here by Camus.

Commentary with Charlton Heston, Janet Leigh, & Rick Schmidlin [1999] on the Reconstructed Version

What a terrific opportunity for the cast to find out various aspects of the production that they were not privy to at the time. It seems the scapegoat on the shoot was the sound recordist that Welles tried to confound at every turn. There is a film industry trick that I found out about reading and re-reading Bob Balaban's diary on his time acting in Close Encounters of the Third Kind. To get through a day a scapegoat is created from within the crew and although it is an arbitrary choice, it gives the cast and crew a way to vent frustration (in private). Also, to my astonishment, there are CG fixes in the restored cut. No, no, we're not talking about the addition of a spaceship and alien hordes descending on the border town of Los Robles. Some of Welles suggestions asked for changes that may have not been available in the rushes. One of them included the idea that Quinlan's eye line should be different at the end of an early scene – so it was made so with CG. Astounding!

The whole commentary is chock full of wonderful production detail. Heston didn't even know the movie was very loosely based on the novel Badge Of Evil. It's fascinating to have the reshoots by the studio identified. It's also very tempting to be pretentiously blasé and say "Oh, of course Welles didn't direct that shot..." but that's not as easy as it looks because it's about what works for the story. Welles actually praised some of the new scenes for injecting more clarity. If you really want to see a jarring shot not in keeping with the director and camera person's intentions, look no further that Hitchcock's classic Vertigo and the restaurant scene. There's a shot of Kim Novak that is so bland, flat and so different to everything that came before and after that it's extraordinary it managed to stay in the movie. Both Heston and Leigh (then in their elder years let's say as they are now, alas, both gone) are charming but also lively and still showing great affection and respect for this small masterpiece. Schmidlin makes an excellent, if unsurprisingly overawed, moderator.

Commentary with Rick Schmidlin [2008] on the Reconstructed Version

This is an absolute utter gem of a commentary. Why? Because Rick Schmidlin is one of us – a cinephile who got lucky, a movie nut, a geek who lucked into working as the restoration producer on an amazing film with extraordinary people. To paraphrase him, "I went from being a movie geek to working on an Orson Welles movie with Marlene Dietrich!" Apparently Welles wanted the widescreen cut from the outset. This was an era when super-exec/agent Universal's Lew Wasserman could see the writing on the wall (or in this case the television set in the corner) and so wanted to emphasize the difference a cinema visit makes.

Because of the quality of the work being done, Schmidlin was initially downcast that a full restoration could not be achieved – this is until a studio exec saw the value of his work and gave an extra $40K for a digital restoration. It's because of this, the movie looks minted, new and improved – marvellous. Schmidlin talks about one of the original editors of Touch of Evil and how this wonderful man pulled out a box of late 50s correspondence and gave it to the restoration project. This turned out to be a goldmine of sorts – original memos from Welles, just a treasure trove of insight and creative power. One item moved restoration editor Walter Murch to tears outlining one of Welles' specific sound ideas – exactly the same one that Murch believed he had created for American Grafitti. To no one's astonishment, Welles had got there first.

It's hinted that Hitchcock was a big fan of Touch Of Evil and that The Night Man (played gloriously by Dennis Weaver) was an obvious forerunner of Norman Bates. That poor Janet Leigh and her choice of motels. When Welles delivered his first set of rushes (an extraordinarily complex 4 minute interior shot that effectively put the crew ahead of schedule) the executive reaction was "That's just Orson showing off..." Schmidlin doesn't skirt the Charlton Heston and politics issue either but having said that he adores the man and being able to call him 'Chuck'. There is some astonishment that the film is still known as being a 'B' movie (with that cast?) and the little known fact that this was Henry Mancini's first movie score (the IMDB doesn't bear that out but I'll go for it for now). This commentary is a goldmine of information but merely one of four goldmines...

Commentary with F. X. Feeney on the Theatrical Version

Critic F. X. Feeney waxes poetic about the first shot but also confirms what Slarek and I both agreed about – we all loved the Mancini score over the first shot. Of course we've all lived with that version for many years. Murch's complex overlapping of location sound in the restored version is also effective but that score... Feeney underlines the taboos that were being teased and broken in the film. It's difficult for a 2011 audience to appreciate just how daring this movie was in 1958. Feeney says "Small wonder there's an explosion when these two kiss..." Of course Heston plays a Mexican with sometimes too much dark make-up and the idea that a Mexican man and an American woman could be even seen together. My word.

Some of the detail that flew right by me is that the poster of 'Zita' that is horribly destroyed by acid meant for Heston is a reference to the character of Zita who is horribly destroyed by the bomb in the opening (she's the lady who complains about a ticking sound in the car). There are many instances of information overlap as there had to be but it's insignificant as each speaker comes at the information from a unique angle. Feeney reveals that some trusted source worked out that of the seven million listeners to Welles' infamous broadcast of War Of The Worlds, one million were affected by it and bought its premise.

Feeney also tackles the Heston/Politics issue and comes to the conclusion that if there was one thing Heston valued above all others it was freedom. So he went from being a liberal to a libertarian. I can't square that off with staunch right wing ideals but we'll let that one go too. He caps off his excellent contribution to the greatness of this film with, for a critic, a surprising announcement. He says that "Touch Of Evil is a deeper and wiser film than Citizen Kane..." Big words and there's a lot to be said in favour of that view (as there is a lot being said on this plethora of commentaries and we haven't even got to the Welles experts yet).

Commentary with James Naremore & Jonathan Rosenbaum on the Preview Version

These gentlemen are the Welles experts, Rosenbaum having been brought in by producer Schmidlin to keep the restoration effort as 'Wellesian' as it could be. As hoped, these two approach the film from another angle. They talk about the political context of the film and confirm that Touch Of Evil was Welles' least politically correct film. They also bring up issues that would never occur to me even after having seen the film many times. Just why would a man on his honeymoon bring his wife to the sparse, violence prone streets of Los Robles? The only thing to do here is get harassed by hoodlums. What a honeymoon.

It's revealed that the journeyman director Harry Keller shot the scenes deemed by the studio vital to make sense of the narrative. There are some appalling lapses in continuity between what was originally shot and shot after Welles' departure but they are only noticeable when they are pointed out. There's a line in the film pertaining to Quinlan leaving his walking stick at the murder scene, a line that is ripe for cinematic scholarly interpretation – "A cane that gets left behind..." Lovely. It's nice to see Mort Mills getting some recognition. He's Vargas' only friend in the film and another link to Psycho – he plays the cop with the sunglasses pulling Janet Leigh over.

Dennis Weaver's performance also gets a nod, once described as a "spastic woodpecker" (it felt almost naughty just spelling the word but remember, the past is a different country). Tiny bits of detail continue to astound me. Once the restoration was complete, it was shown to Rosenbaum who immediately asked "Where's the punch?" – a sound effect of Quinlan roughing up his suspect while we're on Vargas in the bathroom. You get the distinct impression that these men really know their stuff. Oh, and Janet Leigh did half of this movie with a broken left arm!

The stand out scene inviting the Hayes Code's wrath (the US censor at that time) was the explicitly suggested gang rape scene of Janet Leigh in the motel room. It's all done with low angles and menacing stares but its power remains undiminished even though Leigh is visually manhandled just the once. The actress claims she performed this herself but even a Blu-ray's detailed picture didn't give me enough detail to confirm this. I suspect it was a stuntwoman. If you have a healing broken arm, you're not going to be flailing for your life as several 'delinquents' pick you up off a bed.

The scholars confirm that the studio cut with the reshooting and the re-editing was hard to follow (phew, it wasn't just me then). The movie was released with no press shows (in the industry, this is because the studio feared widespread negative reaction and have all but given up on the project) and little fanfare despite the A-list talent on display. It didn't do well (what a surprise) but it's heartening to see it receive this kind of attention 65 years later. It's also nice to hear the two confirm the importance of editing. My favourite Welles quote ("...As for my style, for my vision of the cinema, editing is not simply one aspect; it's the aspect.") was referring to the editorial debacle that plagued this wonderful movie. I'll give writer/director Paul Schrader the last word. About Touch Of Evil, he said "It is the epitaph of film noir," and what a glorious epitaph.

Bringing Evil To Life (20:59)

A talking heads documentary on the inception and production of the film featuring both Charlton Heston and Janet Leigh and it's a delight. A lot of the stories are well known to Welles fans but it's nice to have them all under one roof so to speak. Also great to see Dennis Weaver still talking about a role that in any other movie of that time, would have been long forgotten or if not, the only memorable thing in that 'any other' movie. Director Peter Bogdanovich, a one-time friend and advocate of Welles, provides all the background Wellesian detail.

Evil Lost And Found (17' 06")

Unless I blinked and missed it, this feature has no title actually contained within the film itself. Odd. This is the story of the film's reconstruction based on Orson Welles's reaction to the studio cut and his subsequent and infamous fifty-eight page memo. All those involved remember in great detail the aftermath of the shoot and the delivery of Welles's first cut. Cinematic history is often made by the smallest of incidents being granted huge weight. According to Rick Schmidlin, the producer of the restored version, a woman left the preview screening of the original 108 minute version and announced "That was the ugliest and dirtiest movie I've ever seen!" and hit a Universal Exec with her handbag. That Exec then went back and took ten minutes out of the cut, holing it under the waterline according to Welles. The director mistimed his trip south of the border after delivering his cut of the original Touch Of Evil. If he wasn't there to argue his case, the studio could ride rough shod over his wishes and it's not insignificant that Welles never directed a movie in America for the rest of his life.

Original Theatrical Trailer (2:09)

The desperation of a studio seen through the over egging of a certain pudding. For all we can glean from the start of this trailer, the movie is about whether Janet Leigh is going to get gang raped or not. Appalling! It's fascinating to see how even the marketing of the film acknowledged Welles's own reputation. You get a sense they're almost apologising for his uniqueness. That says more about the cookie cutter nature of Hollywood at that time. But it's a typically 50’s garish example of the genre. Well worth what sometimes feels like a voyeuristic look.

The following special features are new to this edition, and are reviewed here by Slarek

Included on the first disc are three newly filmed interviews with notable film writers, and while this may sound like a recipe for repetition, all three are distinctly different from each other in content, approach and style, and are welcome additions to an already comprehensive collection of special features.

Kim Newman on ‘Touch of Evil’ (27:17)

Author and critic Kim Newman is always excellent value for money, and he’s on typically fine form here, kicking off with the suggestion that all of the legends about the film’s production are encapsulated by the sequence in Tim Burton’s Ed Wood where the titular Wood meets Orson Welles in a bar. In exploring the story of how Welles landed the job of directing Touch of Evil, Newman takes a detailed look at the career of producer Albert Zugsmith, as well as how he may have helped to shape the project and the influence he may have had on some of the film’s content. He notes that neither Vargas not Quinlan are exactly likeable, suggests that Dennis Weaver’s wild performance is a Tales From the Crypt version of humanity, and that Welles clearly enjoyed having full access to studio resources for this production. His gift for evocative description is in top gear when he says of the lovely final scene that it’s a “remarkable finale to a film that seems to have left rubble behind it.”

Tim Robey on ‘Touch of Evil’ (19:21)

Critic Tim Robey explores the film from a different angle to Newman, focussing primarily on the Shakespearean influence that Welles brings to his work, to this film, and to the character of Quinlan, highlighting links between the film and several Shakespeare plays along the way. He discusses Quinlan’s racism and how the story was deepened by Welles’ decision to make Vargas a Mexican (in Whit Masterson’s source novel, Badge Of Evil, he was an American assistant district attorney named Mitch Holt), and highlights that mid-film single-take shot, which tends to get overshadowed by the famous opening. The links we’ve probably all made to Psycho are noted, but Robey also cannily finds echoes off the film in works as diverse as West Side Story and In the Heat of the Night.

Matthew Sweet on ‘Touch of Evil’ (17:08)

Sporting what looks like a Two Ronnies t-shirt, journalist, broadcaster, author and screenwriter Matthew Sweet also pursues an alternative avenue of discussion, exploring the film’s late noir sense of moral darkness and intriguingly suggesting that it portrays the world “in putrefaction, or the demise of life,” a place where it appears that the sun has gone out. Had I not even seen a frame of the film, that alone would make me want to watch it. He suggests that everyone in the film feels “smeared in something,” and that it could almost be taking place in the zombie apocalypse. He notes that Marlene Dietrich seems to exist in a different space to the other characters, draws parallels between the film and Moby Dick, and is left speechless when discussing the motel attack on Susan.

Book

A quick comparison with the booklet that accompanied the previous Eureka Masters of Cinema Blu-ray edition makes it immediately evident that, despite the carrying over of most of the content to the book included with this release, it has been expanded on here, hence the page count increase from 56 to 80. Kicking things off is a glowing and unsurprisingly insightful 1958 review of the film by François Truffaut, written just six months before he began shooting his extraordinary debut feature, Les quatre cents coups. This is followed by a similarly thoughtful essay by Truffaut’s fellow countryman, the renowned film theorist and critic André Bazin, and a more in-depth examination of the film, its themes, and its subtext by Terry Comito, excerpted from an essay originally published in a 1971 edition of Film Comment. Next, we have extracts from interviews with Welles about the making of the film, the art of filmmaking in general, the influence of Shakespeare plays, and the film itself, and his comments are often revealing – “My sympathy is with Menzies, and above all with Vargas,” he states. “But in that case, it is not human sympathy. Vargas isn’t all that human. How could he be? He’s the hero of a melodrama. And in a melodrama, the human sympathy goes, of necessity, to the villain.” Then we have an essay written by Welles himself and published in International Film Annual in 1958 in which he reflects poetically on the artistic and technical opportunities offered by filmmaking, after which is a useful timeline-driven piece on the different versions of Touch of Evil.

Now we get to the new material. First up is an essay on the film by film critic and lecturer Richard Combs, which is tantalisingly titled, Tourists in Paradise or, who cares who killed Rudy Linnekar?. A couple of small typos seem to have slipped through here, but the piece makes for such fascinating reading that I really couldn’t care. And Combs is not done yet, as next up is a second essay, Who’s the Jane? Now About These Women, which focusses on the film’s female characters, specifically those played by Janet Leigh and Marlene Dietrich. Again this makes for a compelling read. Then comes the real humdinger, with Orson Welles’ much discussed memo to Edward I. Muhl, Vice-President in charge of production at Universal-International Pictures, reproduced here in its entirety. In it, he outlines the reasons for his unhappiness with the now-lost interim cut of the film, and specifies the changes that he would like to see, which were finally made in 1998 by Rick Schmidlin and editor Walter Murch.

What has not been carried over from the earlier booklet is a short but interesting article in which the two different aspect ratios that the Reconstructed and Theatrical versions were originally presented in are discussed. It’s a piece whose final paragraph opens with the statement, “As such, given that no single, definitive version or ‘director’s cut’ exists, we thought it authentic, and appropriate, to present the film in both ratios on all three versions,” (in the end, they had to settle for two, as no 1.37:1 print was available of the Preview version). While it’s understandable why this was omitted from this edition, it might have been nice to see a it replaced with a short piece explaining why 1.85:1 has since been selected as the definitive aspect ratio. Also missing is the page that provides some specifics of the restoration process, information that I’m sure would be of interest to many and used to be common in Eureka booklets. That aside, a phenomenally good physical extra.

If you can live with the absence of the Academy ratio presentation of the Theatrical and Reconstructed versions of the film that were included in the previous Blu-ray package, then for fans of Touch of Evil this is a dream come true. Assuming you have an HDR-compatible player and screen, the picture and sound are a serious upgrade over their Blu-ray predecessor, and not only have all of the terrific special features been carried over from that release, but they’ve been joined by three fine interviews that each offer new perspectives on the film, and the booklet has also been substantially expanded on. A brilliant release that gets our highest recommendation.

1. https://www.wellesnet.com/rick-schmidlin-on-re-editing-orson-welless-touch-of-evil/

2. It’s been widely claimed that the gang leader, played here by Mercedes McCambridge, is meant to be seen as a lesbian, a risky move for any movie made in the late 1950s. That she dresses and behaves in what would once have been described as a butch manner and has a constantly present, more feminine female companion does lend considerable credence to this reading.

|