| |

“We all want to live. And in large part we make our logic according to what we like. But not having attained our aim and continuing to live is cowardice. This is a thin dangerous line. To die without gaming one’s aim is a dog’s death and fanaticism. But there is no shame in this. This is the substance of the Way of the Samurai. If by setting one’s heart right every morning and evening, one is able to live as though his body were already dead, he pains freedom in the Way. His whole life will be without blame, and he will succeed in his calling.” |

| |

Yamamoto Tsunetomo – Hagakure: The Book of the Samurai |

Show, don’t tell is a favourite filmmaking maxim that favours revealing plot and character details visually instead of spelling them out through dialogue, but if thoughtfully handled, the verbal approach can also be effective. Both styles are put to effective use by director Jim Jarmusch in the opening scene of his enigmatically titled 1999 crime drama, Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai. The film begins with an almost dreamy opening title sequence that alternately follows and takes the viewpoint of a pigeon as it flies over the streets of Jersey City by night before coming to rest on a rooftop pigeon coop, swept along on its journey by the smoothly seductive hip-hop music of Wu-Tang Clan founder, The RZA. The camera then drifts inside the adjacent wooden shack, where a stocky African-American man with braided hair (Forest Whitaker) is sitting silently engrossed in a book that the camera comes to rest on in clarifying close-up. The work in question is the above-quoted Hagakure: The Book of the Samurai by Yamamoto Tsunetomo, from which we then hear the man quoting in voice-over as the words appear on screen in the book’s elegant typeface. The first line that he delivers – “The way of the Samurai is found in death” – will prove to significant in a number of ways. As he reads, the camera observes the battered tabletop in front of him, on which lay two automatic pistols fitted with silencers, a sharp-looking machete, a soldering iron, two circuit boards, a craft knife, and a magnifying glass, items that that provide an indication of his likely profession. If you’re quick enough, you’ll may also spot that his makeshift bookshelf has works by William Shakespeare, Eldridge Cleaver and William Faulkner sharing space with Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee and The Autobiography of Malcom X.

The man’s real name is never revealed, but he calls himself Ghost Dog, and the hints at his profession provided by the opening scene are soon confirmed, as he exits his shack, dressed down in a hooded jacket and carrying a briefcase, and walks unhurriedly but with obvious purpose into the dark and sparsely populated Jersey streets. He raises a hand of affinity to a graveyard as he passes, and pauses briefly to look thoughtfully at the moon. His soulful, slightly sad expression never changes, and no-one he passes even acknowledges his presence, behaving as they might should a real ghost move invisibly between them. Eventually he spots what he has been looking for, a car that he can steal with the aid of a self-built electronic lockpick, a device that shares bag space with one of the guns from earlier. Once on the move, he slips a music CD into the car’s stereo and drives for some distance without a flicker of emotion, his only words being the quotes we hear and see from Hagakure.

When he reaches his destination, he dons a pair of fingerprint-concealing white cotton gloves, and uses a second gadget to eavesdrop on a phone call taking place inside the apartment outside which he has parked, and the voices and the language used clearly suggest that the two men conversing are mobsters. The man inside the house is named Handsome Frank (Richard Portnow), and he is being cautioned by ‘Uncle’ Joe Rags (Joseph Rigano) not to mess around with the boss’s daughter. “She’s been in and out of hospitals for psychiatric evaluation,” he tells him, “She’s a real fucking wacko!” None of this seems to bother Frank, even when Joe tells him that his behaviour might get him whacked. As we watch Frank argue with Joe, the camera slowly glides around him to reveal that the daughter in question, Louise Vargo (Tricia Vessey), is indeed in Joe’s apartment, reclining in a chair by the window and reading. Having heard enough, Ghost Dog switches off his listening device and loads his gun.

Intriguing though all of this is, in no small part thanks to Forest Whitaker’s magnetic screen presence, opening titles aside, it has none of the offbeat and eccentric elements that identify this as what the faithful had at that time come to regard as a Jim Jarmusch film. The first sign of how this might be about to change occurs as the film cuts on the sound of Ghost Dog’s gun being loaded (nice edit, by the way) to a three-shot that has Louise’s mob boss father, Ray Vargo (Henry Silva), sitting at a table and flanked by his cigar-smoking second-in-command, Sonny Valerio (Cliff Gorman), and his ageing consigliere (Gene Ruffini). The first time I saw the film I remember laughing out loud in surprise at this reveal, not because of any specific comical behaviour, but because of how two of this trio appear. The man I was soon to learn was Vargo has the appearance of someone who had been mummified whilst in a state of shock, while his older-than-God consigliere is sat staring blankly into space, and both appear to be frozen in time. The next time we see them, both men make good on the eccentric promise of this first appearance.

As Vargo and the consiglieri sit waiting for an unspecified something to reanimate them, Sonny is called outside to speak to perennially nervous low rank operative Louie (John Tormey), and as they walk and talk it becomes clear that it was Sonny who ordered the hit on Handsome Frank at Vargo’s behest, and that Louie gave the job to his “special guy,” which by now we know just has to be Ghost Dog. Louie is less than happy about ordering the assassination of a made guy, and reassures Sonny that that “the girl” was put on a bus to the seashore, unaware that the girl in question is not on a bus at all but sitting in Frank’s apartment reading Rashomon while Frank sits in his underwear watching a Betty Boop cartoon. When Ghost Dog appears in the apartment hallway, Frank instantly assumes that he’s broken in looking for valuables, so gets s real surprise when Ghost Dog plants silenced bullets in his stomach, chest and head, a pattern directly influenced by Japanese ritual suicide. Sensing the presence of a second person, Ghost Dog steps smartly into the room and points his pistol at the head of the only slightly startled Louise, who instantly assumes that her father has sent him here to kill her. Ghost Dog says nothing, instead picking up the tossed-aside copy of Rashomon. “It’s a good book,” Louise tells him quietly. “Ancient Japan was a pretty strange place. You can have it. I’m finished with it.” Against expectations, Ghost Dog takes the book and departs.

Frank’s death is mourned by those unaware that his execution was ordered by Sonny on behalf of their boss, who is less than happy to discover that his daughter was in the apartment after all and witnessed his execution. The fact that nobody was aware that Louise got off the bus and returned to Frank’s apartment cuts no ice with Sonny, who tells Louie that the only way to sort this problem is to “eliminate the scumbag who whacked Frank.” Under threat of being buried next to him, Louie spills all he knows about Ghost Dog. He reveals that he pays him once a year on the first day of autumn for the contracts carried out over the past 12 months, that they communicate via a carrier pigeon that visits him every day, and that he first encountered him eight years earlier when he saw him being beaten up by three white guys and decided to intervene. Four years later, Ghost Dog showed up at his door and told him that he owed him for saving his life, and they laid the foundations for their current arrangement. Louie tries to make a case for Ghost Dog’s perfect track record, but Vargo still wants him dead, and confirms that every member of his organisation has now been tasked with eliminating him. “This guy’s a professional,” Louie nervously cautions them. “Going after him could be very dangerous.” Oh, you don’t know the half of it.

In the overall arch of its plot, Ghost Dog doesn’t really take us anywhere new. What makes it such a richly arresting and enjoyable watch lies in the ways in which Jarmusch textures almost every scene, often in a manner that usurps familiar tropes, which has the effect of transforming the conventional into something that feels repeatedly fresh and original. In making Hagakure Ghost Dog’s bible, Jarmusch draws on a number of cultural and cinematic influences, with the shadow of Jean-Pierre Melville’s seminal Le Samouraï looming particularly large. This is evident in the isolated existence and humble living conditions of each film’s protagonist and the silent way they go about his business in the early scenes (we’re over 30 minutes into the film before Ghost Dog speaks to anyone), as well as Ghost Dog’s electronic version of the keys that the earlier film’s Jef Costello carried with him steal cars. Jarmusch also twice pays direct homage to Suzuki Seijun’s 1967 cult yakuza movie Branded to Kill [Koroshi no Rakuin] – once involving a bird, the other a drain – which Jarmusch has cited as his favourite hitman movie.*

What fascinates is the way Jarmusch laces the film’s more realistic components with the sort of oddities that we often encounter in real life but that rarely make their way into the more stripped-down, expedience-driven version of reality generally found in Hollywood movies. Thus, we have members of a New York mafia crime family who really look the part (it’s been noted that the similarly well cast The Sopranos first hit TV screens just four months before the release of this film, so must have been in simultaneous production), but whose boss often sits like a switched-off robot, whose consiglieri is an ageing and semi-senile racist, and whose chief enforcer is a fan of 80s rap music with a particular fondness for Public Enemy’s Flavor Flav. Ghost Dog’s closest and possibly only friend is Raymond (an engagingly energetic performance by Isaach De Bankolé), a relentlessly chatty Haitian ice cream man who only speaks French, and with whom he converses and to whom he communicates even though neither man understands a word that the other is saying. There’s even an air of the eccentric and unexpected about the background characters, who include a man who is building a boat on his garage roof (“How the hell is he ever going to get it down from there?”), and the seemingly doddery old-timer that Ghost sees being targeted by a mugger, but who turns out to be a skilled martial artist who is perfectly capable of defending himself. Just about everyone we see watching TV is captivated by cartoons that have an indirect connection to the story, and hard man Sonny gets all evasive when badgered for unpaid rent by two separate landlords, one of several subtle signs that this is a mafia family in decline.

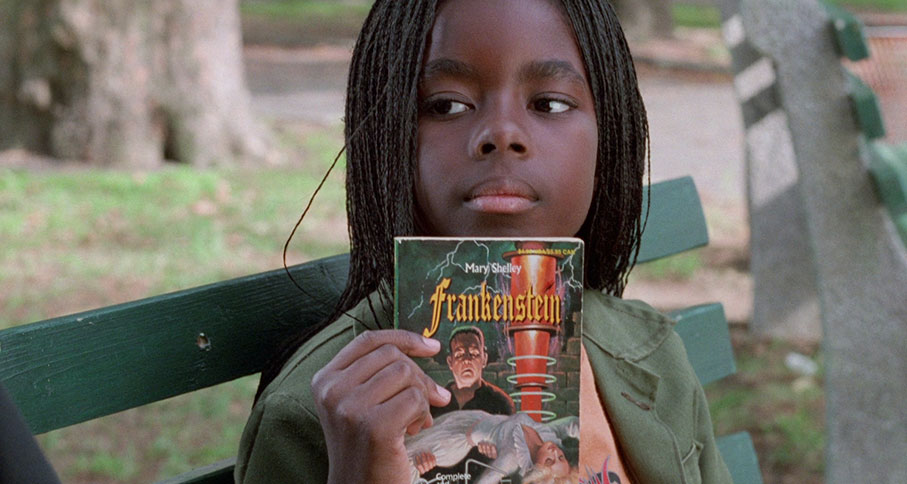

On the flipside of this is the very real skill and ruthless efficiency with which Ghost Dog carries out his hits, with the amount of his potential targets increasing in number when the mobsters overstep the mark and do to his pigeons what similarly foolish Russian gangsters would later do to John Wick’s dog. It’s in his love of his birds that the first signs of Ghost Dog’s inner humanity are first really glimpsed – as he lets them loose and watches them fly, his previously dour expression breaks into a smile of wonder and delight. Our bond with him strengthens later the same day when he’s sitting on a park bench and is questioned by a young girl named Pearline (an effortlessly charming Camille Winbush) with whom he strikes up a friendly conversation about the books that carries with her in her lunchbox. He introduces her to Raymond and lends her the copy of Rashomon on the promise that she’ll come back and tell him what she thought of it, unaware of the cyclic role that this book will play in his own story. Even before this is confirmed, it’s hinted at when Pearline’s initial assessment – “Ancient Japan was a pretty weird place” – is almost exactly the same as the one offered earlier by Louise. And it's hard not to root for Ghost Dog when he pauses a journey to confront a couple of racist white bear hunters who make the big mistake of threatening him with a shotgun, which prompts a response that that I have a feeling comes from Jarmusch's heart. More power to you, sir. I’ve been a fan of the cinema of Jim Jarmusch since his breakthrough microbudget 1984 second feature Stranger Than Paradise (1984) and its glorious follow-up Down By Law (1986). I’ve treasured so many of the films he has made since, from the multi-story delights of Mystery Train (1989) and Night on Earth (1991), to the superb monochrome acid western Dead Man (1995), which is directly referenced here in the reappearance of that film’s Native American spirit guide, Nobody (again played by Gary Farmer). He even gets to repeat a favourite line from the earlier movie when he calls overweight and breathlessly unfit mob enforcer and Sammy the Snake (Vinny Vella) a “Stupid fucking white man” after he shoots one of Nobody’s pigeons, an act of childish frustration at picking the wrong roof in his search for Ghost Dog.

For all of its engaging quirks and strong indie vibe, Ghost Dog remains one of Jarmusch’s most easily accessible films, particularly for those coming fresh to his oeuvre from a more mainstream movie perspective. The lone assassin who becomes personally involved in his work in a way that puts him at odds with his employers is still being recycled today, just recently by screenwriter Andrew Kevin Walker and director David Fincher with their Netflix funded 2023 feature, The Killer, and the dark pleasures and serious undertones that come with that subgenre are certainly present in Jarmusch’s film. What differentiates Ghost Dog from a fair few of its ilk lies in how convincingly it presents the human side of its titular assassin, a role that was written specifically for Forest Whitaker (Jarmusch has repeatedly stated that had Whitaker not been able to take the part, the film would not have been made) that the actor completely immerses himself in. His deadpan interactions with Louis – whom he regards as his retainer and to whom he remains stubbornly faithful – contrast fascinatingly with his friendly park bench chat with Pearline and his bilingual interactions with the effervescent Raymond, with whom he seems to be able to communicate on an instinctive level. He may not come across as emotionally vulnerable as Jean Reno’s Leon, but he is, in his way, every bit as a likeable and as lethally good at his job.

Handsomely shot with an eye for realism by the great Robby Müller, and driven along by The RZA’s seductive hip-score, Ghost Dog is a work that showcases Jarmusch at the top of his considerable game, and in a way that does not require a grounding in American indie cinema to appreciate. It’s a film that both plays to convention and inventively turns it on its head, one littered with memorable scenes and characters, and that, in its own distinctive way, is every bit as Zen as the enigmatic individual after which the film is titled. It’s also one of those rare films that I can go back to endlessly and never tire of, each time spotting some small detail that I previously missed, and for all his great screen performances, this is the one that always comes first to mind when I think of Forest Whitaker. He is Ghost Dog, and Jarmusch was right, he just couldn’t have made this remarkable film without him.

If the trailer in the special features is any indication, the 1.85:1 transfers on both the 4K UHD and the 1080p Blu-ray included with this release were sourced from 4K restoration supervised by Jim Jarmusch, which I’m assuming was also the one used for Criterion’s 2020 US Blu-ray release. This is a strong restoration and transfer with a very good level of detail, and a generous contrast range whose strong black levels do not swamp key picture information. This is crucial for a film in which a dark-skinned protagonist is photographed at night dressed in a hooded jacket, but never is Whitaker’s calmly expressive face lost in shadow, and the skin tones appear to be spot-on. In the deliberately muted palette, bright colours are rare, but when they do make an appearance – a neon sign in the background, or the red jackets of the street gang members who greet Ghost Dog respectfully as he passes – they are most attractively rendered. As you would expect, there’s not a scratch or dust spot to be seen.

As for the difference between the Blu-ray and the UHD, well, that’s a tougher call. The transfer on the UHD has HDR enhancement, and although my TV refused to offer up specifics on this, the lack of the usual Dolby Vision notification suggests this was HDR-10. Comparing the Blu-ray and the UHD side-by side, I did observe slightly crisper detail on the UHD, and the 4K image does have an even more filmlike texture, something particularly evident in exterior scenes set in daylight or the blackness of night. In other respects, the two transfers are visually closer than I might have expected, which I’m putting down in part to the excellent quality of the Blu-ray transfer and the upscaling capabilities of my UHD player and TV. Viewing screen size will likely make a difference here, and while both look similarly impressive on my 55” screen, it’s likely that the advantages offered by the UHD would be even more evident on screens measuring 65” or above. For the record, the screen grabs here are from the Blu-ray transfer.

Both the Blu-ray and the UHD feature DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround soundtracks are in excellent shape, with clear stereo separation on the front channels, subtle use of the surrounds, superb clarity across a wide tonal range, and some thumping LFE bass on the RZA music tracks. A late film thunderstorm is gorgeously recorded and mixed, hitting all of the speakers with crystal clarity and rattling the room with the subwoofer bass.

Optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired are available, but there are enough spelling quirks to confirm that this American rather than British English presentation, which is a little disappointing for a disc being released on the UK market. If you select the German version at the very front end, you'll get German menus, and the film will play in English with German subtitles.

There is one potential problem here, however. In the trivia section of the film’s IMDb page, it’s claimed that the film was initially screened in the US without subtitles for the scenes in which Ghost Dog converses with Raymond, and that when Jarmusch and the distributor discovered this, new prints were struck with subtitles to clarify what Raymond is saying. On the Studiocanal disc, however, these scenes are not subtitled, and if you activate the SDH subtitles, a subtitle appears that just says “[speaks French]” whenever Raymond talks. Given that Ghost Dog does not understand what Raymond is saying, that would seem to make sense, but the 2020 Criterion Blu-ray, which was produced in direct collaboration with Jarmusch, Raymond’s dialogue is subtitled, and some of what he says is directly relevant to the plot. So while I’m happy to be proved wrong, it does look like Studiocanal has really slipped up here.

All of the special features are on the Blu-ray disc only.

Ghost Dog: The Odyssey (21:21) standard definition, 4:3

Made by Artisan Entertainment and Black Entertainment Television in 2000, this extended EPK is built around interviews with writer-director Jim Jarmusch, lead actor Forest Whitaker and score composer RZA – sometimes alone and at others sitting together – and narrated with almost comical gravitas by Dave Fennoy in the style of Trailer Voice Man. If you’re new to the film and the background to its making then this should make for interesting viewing, as the genesis, preparation, production and lead character are discussed, as is the score and the selection of some of the actors who play the mobsters.

Deleted Scenes (5:05 720p)

There are four scenes included here, though only the first one really counts as a deleted scene, and it’s a significant one. In it, a new yuppie mob accountant (Scott Bryce) makes it clear to Sonny, Vargo and the consigliere that most their businesses are now in the red, more clearly indicating that the family is behind the times and in slow financial decline. This is followed by an alternative edit of Ghost Dog’s rooftop martial arts practice montage, a static shot of Raymond advertising his wares in French on his truck’s loudspeakers (a slow dolly shot of the same is used in the film), and an extended version of the scene in which Sonny dances and raps Public Enemy’s Cold Lampin’ with Flavor in his bathroom.

Original Trailer (0:52)

More a teaser than a trailer at this length, but a decently cut together one that does give a small flavour of the film’s content and style.

Trailer (1:20)

A very slickly assembled and more recent trailer made to promote the 4K restoration, and one not shy about including some of the film’s stronger language. Even if I wasn’t already a fan of the director and the star, I’d go and see it based on this.

A rare movie that’s as cool and distinctively creative as the masterful works that inspired it, Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai just doesn’t seem to have aged and remains one of my favourite works from a filmmaker I have always deeply admired. It’s a welcome choice for a 4K upgrade, and if you’ve not made the jump to 4K yet, the included Blu-ray still delivers, and having both formats in this package means that that you won’t have to upgrade at a later date. There’s not that much on the special features front (though one of the deleted scene is of interest), but the absence of the subtitles on Raymond’s dialogue is a most peculiar oversight and is likely be a dealbreaker for many. If this doesn’t bother you, then the transfer alone should be enough to recommend this release, but the Criterion Blu-ray is still available for those with multi-region Blu-ray players, and there’s always the possibility that we will see a UHD release of the film from Criterion in the future. There are no guarantees, of course, and it won’t be cheap, but it should include all the special features from that earlier Blu-ray. Your choice.

|