|

Weekend is already turning out to be the little British film that could and if Academy Awards were handed out on the basis of review aggregate, it would be one of this year's surefire frontrunners in many of the major categories alongside predictably obvious entrants The Help, The Artist and My Week with Marilyn. Released in America first, the yanks have already fallen for this in a big way, and in the wake of last month's London Film Festival, similar buzz has already built on this side of the pond in anticipation of its release this past Friday. Already aware of the US raves before I saw the film and not having long dried myself off from Telegraph critic Tim Robey's gushing tweets, it's fair to say that a 94% fresh rating on the tomatometer is something that can do as much harm as it can good for the type of small film whose low-key pleasures are best discovered freshly unaware.

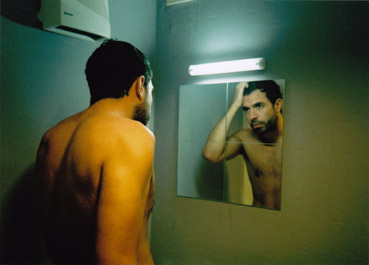

After a lusty one night stand, Russell (Tom Cullen) and Glen (Chris New) agree to extend their tryst over the course of a single weekend, which starts with Glen asking sexually secretive Russell—only a select few of his exclusively straight circle of friends know he's out—to partake in his Sex Lies & Videotape-like art project, interviewing lovers the morning after and having them reconstruct the night's events which may or may not have met with their expectations. All the while that Russell is being prodded into this discussion by Glen, it's clear they're both very excited by one another, and as is the way when you meet someone new and exciting—gay or straight—you don't want the conversation to end. Audiences will find much of what transpires as instantly recognizable regardless of sexual preference, i.e. Russell taking great pains over whether to sign a text message with x or :), so as not to confuse its interpretation. Writer/director Andrew Haigh dresses queer politicising in rom-com clothes (fairground montages and tearful goodbyes at train stations) in an unassuming manner, furtively sneaking gay issues in without risk of alienating other sectors of his audience (though the frank coarseness of the 'dick n' balls' language very well might). While many of the questions raised in conversation are gay specific, Weekend never once feels like an "issue" movie or an eager plea for gay acceptance from straights. Even as Glen challenges a group of straight people who frown upon gays being in a bar that isn't exclusive to them, seconds later he's all too freely admitting that his own kind "are idiots as well, they just dance more." Such offhand observational humour is what gives the film a crossover potential beyond the LGBT circuit.

Glen's keen, unfiltered insights into his own sexuality, and that of the culture at large (on coming out to his bewildered parents: "Nature or nurture, it's your fault, so get over it"), mark him as a take-no-shit authority figure to both Russell and the viewer. Interrupting his own artistic interrogation to hurl abuse back at a gang of bigots outside his window, he's the kind of captivatingly unhinged provocateur who, in the same moment of screaming at homophobes that he'll rape their holes if they don't stop giving him shit, has no problem letting you know that he's got a thing about pits. By contrast, Russell is terrified of kissing in public and is careful not to leave obvious clues of his orientation out in the open; hastily scrambling the fridge magnets with which Glen has spelt the word 'faggot' when he wasn't looking. In sketching the yin and yang of modern gay men that Glen and Russell appear to represent (one singing his sexuality from the eves while the other haughtily guards it), critics have praised the film's kitchen sink naturalism, and the jostling tone has an unscripted quality that makes it all sound very off the cuff—chatter with the impression of unprocessed thought. Bizarrely, many American journalists have identified these traits as having something in common with the New York mumblecore scene, a patently wrong-headed notion, as Glen and Russell have far too much to say, their articulation only stumbled by a desire to say so much all at once. The pair hash out various concerns—including the "ghetto-isation" of queer art—from every conceivable angle, considering wider cultural implications rather than narrow-mindedly speaking from a place of self-entitled ennui.

Russell seems to pass Glen's post-coital assessment, as the two continue to spend the rest of the weekend in each other's company (at the end of which Glen will jet off to art school in America). Worldviews clash, interrelate and finally converge in the mutual respect of silently agreeing to disagree. At the root of Glen's project, which serves as the inciting incident for a weekend of seesaw-philosophising, is the idea that when you sleep with someone you become a blank canvas onto which you can project who you want to be—the gap between the projection and reality is where one finds the truth. It's in that same gap that I found myself questioning the truth of Glen and Russell as a romantic couple. With time ticking down, there's a sense of genuine unfettered candour between these two men as pleasantries are quickly dispensed. Mutually becoming more and more enamoured, both start to really open up and reveal themselves to us, people we stand a chance of really getting to know and not just characters whose behaviour is at the behest of slow-build scripting and a clear three act structure. This brazen honesty is something critics have gone ga-ga for, but a later sex scene hangs a question mark over all that was tender and touching before it. The lovers barely seem to look at each other as they grind away, the film shoving what's best described as unchecked lust in our face with the misplaced pride of a cat bringing a dead mouse to the door. The sudden greater concern with body parts and anatomy, over heart-melting glances, retro-actively cheapens their relationship to the point where the earlier effusive peeling of layers is relegated to an altogether different kind of seduction. Understandably, the scene is tinged with desperation after having reached a point where all verbiage has been exhausted and they're unlikely to ever see each other again, but once this desperation asserts itself as the predominant tone and wilts the blossoming romance for which the film is being celebrated, you have to wonder if the promise made with each other's bodies is an empty one. The rarest and best kind of sex scenes that serve the story beyond mere titillation, use gestures to carry on where the dialogue left off and in this way the carnality must be just as spontaneous if we're to ever see a character for who they really are and learn their secrets. The sex scenes of Weekend only ever feel mechanical and not unlike Glen, childish in their art school provocation. The only secret learned here is that both men are still projecting even at their most emotionally naked. What before seemed like such a genuine, complicit bond of trust was perhaps just another way of hopping back into bed without the pretence of a research project—not just Glen, but Russell too, in the way he consciously tests the barriers of both his queer and straight life, wanting to spend more and more time in one world without ever allowing the two to intermesh.

In light of this double life juggling act, Russell's obvious physical discomfort during a late night visit to a gay bar reads as self aware role playing, a way of openly bleeding to attract sharks. He slips in alone with a casualness that belies his little boy lost routine, indicating he's done this before—perhaps regularly—and posing as a questioning newbie is his own guarantee of getting laid. For all the cautious reserve he shows throughout, it's telling that, after being spied kissing at the local train station, it's Russell who reacts aggressively to a homophobic wolf whistle and not Glen, whose bravado out in public seems to desert him if he's not sufficiently lubed with alcohol. This upending of character brilliantly extrapolates Glen's theory of the unreachable truth between projection and reality, and as a consequence I was deeply impressed by how much thornier the film revealed itself to be. But a thorny film is often difficult to fall in love with, and it's hard to shake the nagging feeling that people are walking out of Weekend enamoured with the projections of Glen and Russell, versus who they really are.

|