"What do these worthies/But rob and spoil, burn, slaughter, and enslave/Peaceable

nations, neighbouring or remote/Made captive, yet deserving freedom more/Than those

their conquerors/who leave behind/Nothing but ruin wheresoe'er they rove." |

John Milton, from Paradise Regained, 1667 |

"I agree with Dante that the hottest places in hell are reserved for those who, in a period

of moral crisis, maintain their neutrality. There comes a time when silence is betrayal." |

Dr. King, from Why I am Opposed to the War in Vietnam, 1967 * |

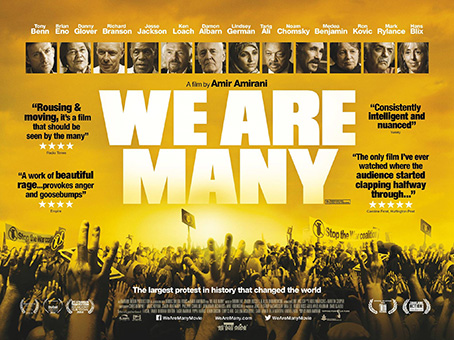

Many remember where they were on the days Kennedy and Dr. King were assassinated. Others can recollect exactly what they were doing as the catastrophic events of 11 September 1973 and 2001 unfolded. Traumatic, if mediated memories of such pivotal political moments haunt our collective nightmares. 15 February 2003, the day countless millions in hundreds of cities worldwide marched for peace, kindles memories and dreams of a different kind. Those who participated in the largest global protest in human history will recall it with pride and joy. Amir Amirani's We Are Many tells the inside story of that extraordinary event. When the film screened at the Sheffield Documentary Festival, it deservedly and fittingly received several minutes of spontaneous, joyous applause.

We Are Many is a finely balanced, brilliantly edited blend of sober analysis and intoxicating feeling. Although it revisits the day the world said No to war, Amirani's film is more, much more than an invaluable aide-mémoire and message to posterity. It's a howl of rage, a rallying cry, and a paean to the politics of hope that presents the two forms of two-fingered salute to shoulder-shruggers and warmongers alike.

It is also a cinematic dossier on the manifest lies of power. In the absence of a ruling from the Chilcot Inquiry, Amirani conducts a forensic examination of the available evidence and presents his own findings to the court of public opinion. He concludes that those who demonstrated for peace were right, in ways they couldn't have guessed, and finds the mainstream media and institutions of State guilty as charged.

Finally, it is a labour of love. In the nine years it took him to make the film, Amirani twice re-mortgaged his house to keep afloat, faced down countless knock-backs and setbacks, undertook the lion's share of the research himself, edited nearly two hundred hours of gathered material over two years, and interviewed well over a hundred people at length (almost as many as Mr Chilcot & Co.).

Amirani has assembled an impressive range of witnesses from within both the anti-war movement and the corridors of power to build his case. 'Go-to' veterans of the left like Tariq Ali, Tony Benn, Noam Chomsky, Ken Loach, and Tom Haydn appear in the film alongside Establishment insider-outsiders like Hans Blix, John Le Carré, Peter Osborne, Stephen Hawking, and Lawrence Wilkerson (Colin Powell's Former Chief of Staff). Wilkerson details the lies used to hoodwink the people and justify the unwanted war. He states categorically that he'd testify "in a heartbeat", even at the cost of facing conviction himself, if Bush, Cheney, and Rumsfeld are ever arraigned. Roll on the War Crimes Tribunal implicitly called for by Damon Albarn, Jesse Jackson, Mark Rylance, Professor Philippe Sands, and Desmond Tutu in the film.

We Are Many describes an arc of interrelated events precipitated by 9/11. It counts down, in turn, to the global Stop the War protest, the illegal war in Iraq, the Arab Spring, and, finally, the Commons vote against intervention in Syria. Amirani deploys a conventional combination of familiar techniques (archive footage, calendar and clock as motors of suspense, mood music, diegetic sound, still images, to-camera interviews) to build a surprisingly radical case. If the film is something of a wolf in sheep's clothing, the urgency of its message may persuade even those who believe radical content demands radical form that reach is all.

It may lack the edge and visual invention of, say, John Akomfrah's The Stuart Hall Project or Nancy Kates' Regarding Susan Sontag, but it displays equal respect for its subject. Amirani was keen to "tell a good story" and make an accessible film without distracting buttons and bows. His BBC training is evident in an adroitly edited film with high production values and the soundtrack has its fair share of bells and whistles. The film begins with a rap from Michael Franti & Spearhead reminding us that, despite what Stephen Pinker says to the contrary, war is the health of capitalism (They gotta war for oil/a war for gold/a war for money/a war for souls/a war on terror/a war on drugs/a war on communists/and a war on hugs). Amirani also makes excellent use of rebel songs like 'Bella ciao' and 'This Land is Our Land', and the way he contrasts sound and silence is particularly effective.

We see Tony Blair stumbling over his words as he attempts to justify the imminent invasion of Iraq at a Labour Party Conference in Scotland. Delegates listen to him in stony silence (but, hey, at least they listened). More generally Amirani contrasts our noise with their silence. That eloquent silence is in marked contrast to the exhilarating sound of protest on 15 February 2003. John Le Carré, who was among the marchers Blair accused of having blood on their hands, says he has never, before or since, heard anything like the sound that arose from marchers as they passed Downing Street. He calls it "a visceral, feral grumble, a roar, a rising sound." John Rees, for his part, chokes back tears as he talks about the demonstration and the "howl of joy" that rose when two rivers of humanity conjoined at Piccadilly Circus.

| The Spark that Lit the Fuse |

|

In We Are Many, Amirani boldly argues that although the anti-war movement failed in its immediate objective, it nevertheless 'changed the world forever': by energising and emboldening Egyptian activists it was a catalyst for the subsequent occupation of Tahir Square and the Arab Spring, by forcing a belligerent British government to heed public opinion it averted Western military action in Syria.

The idea that our parliamentary representatives learned their lesson on 15 September 2003 and consequently voted against intervention in Syria flatters Westminster. It's a comforting thought best taken with a pinch of salt. The colossal scale of the global Stop the War demonstrations certainly gave startled MPs pause for thought, but one doesn't have to be too sceptical to suggest that that benighted country's depleted oil reserves and the disastrous consequences of the 'War on Terror' might also have played on their minds as they voted.

The film's invigorating core thesis, that the global protest was the spark that ignited the fire of Arab revolution is, fortunately, more convincing. Hossam el-Hamalawy describes 15 February 2003 as one of the most depressing days of his life. He recalls the moment the Arab world watched "those white, whisky-drinking infidels taking to the streets on their behalf" and the intense frustration of local activists at the muted response in Cairo. Those activists kept their faith in the Egyptian people, redoubled their efforts, and thereafter matched their Western counterparts stride for stride, with incredible results. Amirani reminds us that courage is contagious and hope is infectious. The film's defiantly positive message that persistence pays and even our defeats bear fruit in unforeseen victories is at the heart of what makes it tick.

| Rehearsals For Revolution |

|

We Are Many opens with the closing stanza of Shelley's immortal poem The Masque of Anarchy, written in response to the Peterloo Massacre in Manchester. Shelley wasn't present on the demonstration that ended in murder. He was in Italy. His incandescent rage and thunderous literary response were triggered by second-hand accounts of the event. Many will learn of the great global anti-war protest of 15 September 2003 through Amirani's film. Among them may be many Shelleys.

Amirani's use of Shelley's words is instructive. Peterloo flowed from earlier events (the Pentrich and Newport Risings, the Rebecca Riots) and into the ensuing era of Chartist agitation. As E.P. Thompson said, Peterloo had unforeseen consequences: " . . . because of the odium attaching to the event, we may say that in the annals of the 'free-born Englishman' the massacre was yet in its way a victory. Even Old Corruption, knew, in its heart, that it dare not do this again . . . the right of public assembly had been gained." Which is to say, Peterloo, ultimately, made political demonstrations like those on 15 February 2003 possible. We gain ground, lose it later, begin again. The truth will out, hope dies last, and we stubbornly dare to dream, in John Berger's fine phrase, "like a dog in its basket, of hares in the open."

In a New Society article of May 1968, Berger argued that mass demonstrations aren't merely barometers of popular feeling and opinion, temporary occupations of public space, or appeals to the conscience of the State (which has none) but, rather, "visible, audible, tangible" displays of collective strength that "express political ambitions before the means necessary to realise them have been created." They are, he says, "rehearsals of revolutionary awareness' and 'any demonstration which lacks this element of rehearsal is better described as an officially encouraged public spectacle." He wrote those words at a time of international insurrection, when more people thought more deeply about politics and fought more tenaciously for change than is now the case, so we must ask what relevance his analysis has to the global anti-war protest and what those demonstrations signified.

Posterity may come to regard 15 February 2003 as the moment the scales fell from our eyes and We, the People finally lost faith in a corrupt, discredited, insensitive and insular system of representation in thrall to corporate power, no longer responsive to people's dreams or relevant to their needs. Amir Amirani suggests otherwise. Like the global peace movement, Amirani seeks the revivification of democracy not its burial. Like Berger, he takes the long view of history and sees demonstrations as harbingers of a better future. In We Are Many, Amira Howeidy, a Deputy-Editor of Al-Ahram, echoes Berger's description of mass demontrations as "rehearsals for revolution." Recalling the Cairo demonstration that coincided with the invasion of Iraq, she says: "Little did we know that that was a rehearsal for the 2011 revolution."

Phyllis Bennis of the estimable Institute for Policy Studies, for her part, describes the way the demonstrations of 15 February 2003 followed the sun, from Australia and the Southern Hemisphere to Antarctica and the North Pole, as they swept across national boundaries and circled the earth like planetary currents. Egalitarian and emancipatory impulses, liberating ideas of peace and human solidarity raced across the oceans that day too. Something both old and new was abroad, as an ancient tradition of radical revolt co-mingled with a distinctly modern form of people-powered internationalism. Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker's magnificent book The Many-Headed Hydra: The Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic tells an apposite story about that tradition and how radical ideas circulate.

Linebaugh and Rediker detail the ways in which the democratic ideas of the English revolution, once deemed utopian, travelled out from the Putney Debates to the wider world, carried by the tides and the common people. During the English civil wars, Gerard Winstanley put into practise his vision of the earth as a treasury for all and temporarily occupied commons that'd been enclosed or privatised. After his 'Digger' colony was destroyed by hired thugs in January 1650, he waited to see the spirit of his ideals "work in the hearts of others" and to see "whether England shall be the first land, or some other, wherein truth shall sit down in triumph."

Linbaugh and Rediker take up the story: "Despite the defeats inflicted by Winstanley's enemies on London Levellers, Irish soldiers, Barbadian servants, and Virginia slaves, truth did sit down in other lands . . . it swayed on the decks of deep-sea ships; it rubbed shoulders with the poor in the taverns of the divaricated port cities; it strained for a hearing on the benches of the churches of the Great Awakening or on stools on the dirt floors of slave cabins at night." Truth travelled then all right, borne by people and within people, as it did on 15 February 2003.

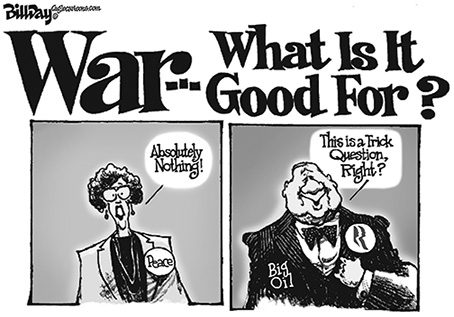

© caglecartoons.com

Truth is the first casualty of war. In the case of the war in Iraq, truth had already fallen before a shot was fired or a cruise missile was launched. In We Are Many, author Patrick Tyler, a former New York Times staffer who cut his teeth working for Bob Woodward on the Washington Post, says of the 'dodgy dossier': "There was a grand deception in which we all share various amounts of responsibility. Everybody didn't do their job . . . The military-industrial complex has its analogue in the press, the media-industrial complex." Indeed. As Captain Willard says in Apocalypse Now: "We cut 'em in half with a machine gun and give 'em a Band-Aid. It was a lie. And the more I saw them, the more I hated lies." Abu Ghraib, Guantánamo Bay, extraordinary rendition, 'smart' bombs, the 'dodgy dossier' - to paraphrase Willard, the bullshit piled up so fast over Iraq, you needed wings to stay above it.

At one point in the film, musician Brian Eno describes how he secured and studied the infamous government dossier on weapons of mass destruction, and then contacted U.N. weapons inspectors to discover for himself what devils were buried in the mass of detail. Eno declares his amazement that he was able, so simply, to secure answers to questions our parliamentary representatives (and, he might have added, a largely supine press) failed to ask. Amir Amirani, too, demonstrates what a single concerned, committed citizen impatient for answers can achieve and unearth. As Dorothy Thompson said, in Over Our Dead Bodies: "We must take back the language of freedom and the practices of democracy from those who are perverting them. Who but ourselves can defend us against these defenders?"

| The Second Global Superpower |

|

The late Christopher Hitchens, who sadly aligned himself with the war party not the peace camp over Iraq, used to check his political pulse daily by seeing if the New York Times still ran its motto 'All the News That's Fit to Print' on its masthead. If he remained as irritated as ever by that asinine, meaningless boast he'd know, he felt, that his contrarian heart was still beating. The offending motto was still there when the paper's 52, 397th edition went to press on 17 February 2003. It sat, that Monday, above a keynote piece by Patrick Tyler which began: "The fracturing of the Western Alliance over Iraq and the huge anti-war demonstrations around the world this weekend are reminders that there may still be two superpowers on the planet: the United States and world public opinion." In We Are Many, Tyler says of "the second global superpower': "We live at our peril in ignoring it, and certainly in denigrating it, because that tends to be the next generation and that is the future."

Nobody can predict the future. Just as nobody could've imagined the Stop the War protest would spark Arab revolution, no-one could've predicted the knock-on effect it'd have in Scotland. The resounding 'No' of 15 February 2003 echoed in the 'Yes' campaign in last September's referendum - which now reveals itself as another victory disguised as defeat. Both the contemptuous silence that greeted mass protest and the Iraq war itself undoubtedly increased Scottish contempt for Westminster and contributed to the SNPs electoral successes of 2011 and 2015. We have surely moved closer to the independent Scotland gleefully prophesied by Tom Nairn when he said: "Any day now the wolves will break into the drawing room, and it won't be the cucumber sandwiches they're after!" Nairn's wolves aren't quite in the drawing room, but the Scottish cats are certainly among the parliamentary pigeons already.

Despite all the trials and tribulation that accompanying the making of the film, Amir Amirani is glad it all took so long. The delays caused by successive financial crises increased the film's scope and reach. It's still a shame the film was finished before events in Scotland took an interesting turn and that Alex Salmond didn't make the cut (only 54 of the 112 interviews Amirani conducted did). It is a crying shame, too, that the BBC, the BFI, and Channel Four elected not to fund the film. This courageous intervention in our culture of violence might've fallen victim to risk-averse cowardice but for a successful Kickstart crowd-funding campaign.

Amirani captures the joy of solidarity and struggle as brilliantly as he reveals the lies told by the Establishment. We Are Many merits a place alongside great anti-war documentaries like Marcel Ophuls The Sorrow and the Pity, Emile de Antonio's In the Year of the Pig, and Eugene Jarecki's Why We Fight. Amir Amirani's commitment was subject to a rigorous inspection between the film's conception and completion. His tenacity and persistence have born fruit in this important cross-examination of power and inspirational argument for change.

This review was first published, in shortened form, by Red Pepper magazine.

* https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b80Bsw0UG-U

|