"Truth has no meaning, unless it has explanatory force,

unless it is knowledge, a product of thought." |

Peter Wollen |

The A5 has channelled waves of migrants north and south for centuries. Stretching between Marble Arch in London and Admiralty Arch in Holyhead, it partially traces the line of the Roman road later known as Watling Street. This was the route on which Caesar's legions, composed largely of Gauls and Germans, marched north to subjugate the Celtic tribes who had themselves only recently migrated here from mainland Europe. The modern road cuts across middle England, ascends into mountainous North Wales, then drops towards the flatlands of Anglesey and the ferry terminal at Holyhead – the point of departure for generations of 20th Century Irish migrants forced south to eke out a living in London.

This is the ancient highway nominally at the heart of Marc Isaacs' latest film, misleadingly titled The Road: A Story of Life & Death. The A5 is over 260 miles long, but Isaacs stays close to his North London home to serve up a slice of life on or around a sliver of the road – essentially the single mile between The Crown Hotel in Cricklewood and the Marriott Hotel, where working-class Kilburn meets bourgeois Maida Vale.

All roads lead to Rome and, although the British and Roman Empires are long gone, the A5 in London still pulses with the energy of adaptable immigrants drawn to the teeming metropolis from around the world. Isaacs introduces us to a few from amongst the millions: to Billy Leahy, a lonely alcoholic once enrolled in the army of Irishmen who built much of England's infrastructure, including roads like the A5; to sparky German Birgitte Krafczyk, a retired air hostess who runs a hostel for language students while caring for her estranged husband Royston; to Nomm Raj, a Burmese Buddhist who renounces his wife back home to become a monk; and to Peggy Roth, a frail Jewish widow who fled Vienna to escape the Nazis.

Isaacs' core cast of emblematic characters is completed by Keelta O'Higgins, an aspiring young singer who pours pints for her older compatriot Billy in an Irish pub in Kilburn; and Iqbal Ahmed, a softly-spoken Kashmiri working as a hotel porter at the Marriott Hotel while impatiently anticipating a reunion in London with his wife, Asia, who he misses terribly. Keelta and Iqbal have surprising significance for our reading of the film. I will come to that shortly. If Keelta represents those who arrive in London with hope in their hearts, Billy, who hasn't been home in 42 years, represents those who learned to walk its unkind streets alone. Keelta and Billy embody the generational shift in the aspirations of the London-Irish. Iqbal, meanwhile, stands in for those who have come from further afield: the Muslim community clustered around the Edgware Road section of the A5, a community Isaacs says he found it impossible to 'penetrate'.

The film is at its most engrossing when Isaacs quietly questions his subjects in the intimacy of their own homes. He seems to have taken talk of 'kitchen sink realism' literally: a couple of the film's most memorable moments occur when he films Billy, Nomm, and Peggy talking frankly . . . at their kitchen sinks. Peggy's mischievous wit illuminates the film when she irreverently discusses her late husband's failings. Nomm, too, provides a dash of humour when he tells Isaacs of his fondness for English food – such as "bagels and fish & chips." The heart-rending scene, in which we watch Billy discuss his alcoholism as he pours himself a morning mug of neat vodka with shaking hands, is more typical of the film's melancholic mood.

Most of us are only too happy to talk about ourselves. Lonely senior citizens craving company and conversation tend to open up more readily than others, when we take time to listen to their remarkable, instructive stories. Isaacs, to his credit, is a good listener. He is also careful to select subjects with eloquent, entertaining turns of phrase. Peggy is not alone in having a way with words. Iqbal describes his experiences with forensic precision, and he speaks for most immigrants when he says, philosophically: "You don't fit in back home and you don't fit in here either."

For his part, Billy has the Irish gift of the gab, in spades. When asked by Isaacs what went wrong with his life, he says, poetically: "I lost my way in the fog." Since retiring, he says, he often finds himself, "a day late and a pound short." Billy and Peggy are typical of the indefatigable survivors Isaacs seems most drawn to, which makes their tragic deaths during the film all the more intensely sad. Audiences may wonder what Marc Isaacs must have felt about Billy's death in particular: he says he found Billy's body in his flat, three days after he died, and wonders, himself, what period might have elapsed before that tragic discovery if he hadn't been filming the Irishman.

There is sadness, of a sort, too, in the film's failure to transform its cast of captivating characters and moving moments into a coherent whole. Isaacs simply doesn't make most of the material he amassed over an 18-month period of simultaneous research and filming. What's more, the sleight of hand and slenderness of ambition suggested by the film's deceptive title is evident throughout the film. For a documentary, even a 'creative' one, The Road is disappointingly selective about the ideas and information it imparts. It is also, as we shall see, disturbingly cavalier in the way it presents the stories it tells and the people it features.

At one point, we join Nomm at the Buddhist monastery at the centre of his life – incongruously housed in a mock-Tudor semi in Colindale; in another scene, we visit a mosque during Muharram to witness the 'matam' breast-beating ritual. Isaacs explains nothing about either faith. Shorn of theological context, the respective rituals of those faiths might strike audiences as either silly or sinister. Isaacs doesn't tell us much about the origins of the immigrants he meets either, thus detaching them from the broader stories of their lives and the wider story of our times, while also depriving his audiences of the information they need to reach their own conclusions.

Even more disastrously, Isaacs no more explores the wider implications or issues of immigration than he does the road itself. His subjects are presented as people bobbing on the mysterious ocean of life like flotsam and jetsam, not as migrants forced to the margins of a fragmented society by economic forces shaped by human hand. Might global inequality and the reliance of Western economies on migrant labour not explain something about the immigrant experience? Might the fact that the world's richest thousand or so billionaires are worth more than one and a half billion of the world's poorest people be worth mentioning, perhaps even challenging?

In his excited search for stories Isaacs doesn't pause to ask such questions, and the film's anodyne narration silences disturbing off-camera noise, lulling us soporifically with bland musings on themes such as the universal drive to find a sense of home. Isaacs reminds us of Orwell's comment on Dickens: "His whole 'message' is one that at first glance looks like an enormous platitude: If men would behave decently the world would be decent."

|

© Martin Gray |

In the absence of the broader picture we are left to fill in the contextual gaps ourselves. There is nothing in Isaacs' film of the nuanced understanding of the Irish immigrant experience present in, say, writer Timothy O'Grady and photographer Steve Pyke's collaborative novel, I Could Read the Sky. Nor does it offer any of the profound insights contained in the book that inspired O'Grady and Pyke's work: writer John Berger and photographer Jean Mohr's analytical and poetic meditation on migration, The Seventh Man.

Although the absence of political and historical context is the film's fatal flaw, its selective sense of place might actually have been the cornerstone of its success – had our expectations not been raised by that exaggerated title. One of the most admirable aspects of Isaacs' work has been his consistent tendency to focus his handheld camera on singular people and places generally overlooked by film and society. In that sense, at least, he is to be applauded for tenaciously taking the road less travelled.

For his wonderful debut short, The Lift (2001), he spent about 10 hours per day, for three months, filming in a council flat lift; for Travellers (2003) he filmed the lovelorn on trains and railway platforms; for Calais (2003) he looked at immigrants caught at a crossroads; in All White in Barking (2008) he hints at the hostile reception migrants often face; and for his last film, Outside the Court (2011), he spent three months filming outside Highbury & Islington Magistrates court.

The what-it-says-on-the-tin honesty of those earlier films is particularly pronounced in The Lift, a minor masterpiece of the documentary form that established the template Isaacs has worked from ever since. Developing his trademark style of conversational curiosity on the job, he gradually drew his subjects out of their shells to sketch a riveting portrait of life in a tower block. Perhaps he intended the film to operate as a metaphor for life's ups and downs, but, whether by accident or design, the people who joined him in that suspended mobile crate cohere to create a compelling composite picture of London's ethnic diversity. The Lift shows what an original idea honestly executed by a man with a movie camera can achieve. It also, coincidentally, points to a possible future for film by demonstrating the potential of alternative distribution channels: it has garnered well-earned 659,883 YouTube views, at latest count.*

Isaacs' latest film is his most ambitious project yet. The first of his films to secure theatrical distribution, it was produced within the BBC's Storyville documentary strand and backed by the Irish Film Board. That institutional backing presented Isaacs with a golden opportunity to expand on the themes of immigration, loneliness and loss that provided the subtexts of his earlier films. He began, as the working title 'The World on the Road' suggests, with no clear sense of direction, just a vague idea of immigration as his theme and the hope that the road might work as the thread to unite a variety of disparate characters and their stories.

The film begins, with considerable promise of thematic coherence, at Holyhead ferry terminal. We are immediately introduced to Keelta O'Higgins, fresh-off-the-boat and setting out for London, guitar and suitcase in hand. The film and the road open up invitingly before us. At which point, Isaacs cuts abruptly to London, which we don't leave again. The Road never recovers from this jarring dislocation. Isaacs loses his bearings as he loses sight of the road, his theme and thread fail to bind, and this patchwork quilt of a film unravels into its component parts.

|

© Martin Gray |

Isaacs is, essentially, a victim of his own success and ambition. He has simply overreached himself. There is an honest force to his first film that his latest one lacks. Isaacs' earlier films sat comfortably in a small screen setting that emphasized their small-scale insights into individual lives. When viewed at home those of his films that have been released on DVD by Second Run retain their intimate charms. In cinemas, however, The Road film stands naked before us, and both Isaacs' limited visual lexicon and the film's lack of thematic depth are glaringly exposed. His talent for coaxing stories out of individuals and creating engaging vignettes is another matter entirely.

There are, it is said, two sides to every story. Here's another story, a story about Isaacs' 'story'. A fortnight ago, I went to see Michael Haneke's Amour at The Tricycle on Kilburn High Road. It is a cinema I love but seldom visit. I was with a Jewish friend who lives off the A5, so, as we chatted before the film began, I recommended Isaacs' film to her as of local interest and suggested that Peggy's story, in particular, might resonate with her. When our screening was over, my friend and I adjoined to the Colin Campbell, the Irish pub opposite The Tricycle which features in the film. There behind the bar, to my amazement, stood Keelta O'Higgins, larger than life. It was like walking into a scene from Isaacs' film. For a split second, my mind returned to the film and replayed images of Keelta singing and Billy drinking where I now stood, wide-eyed and gobsmacked.

After recovering my composure and quietly explaining the coincidence to my friend, I fell into conversation with Keelta. I told her how affecting I'd found the scene, early in the film, in which she stands at an isolated bus stop outside Holyhead, clutching a pillow and blanket, choking back sad tears as she talks to Isaacs about the road ahead and the life she'd left behind. A second surprise followed. A trace of a grimace spread across Keelta's face and she raised her forefinger to her lips – before telling me that she had actually travelled to London a year before that scene was shot, in the company of friends, and made her way to Kilburn via Scotland.

During the week that followed, I revised my opinion of the film in light of the information imparted by Keelta, which helped me to see that Isaacs draws his subjects into a relationship not just of trust, but also of complicity. He coaxes performances out of people as if they were actors, and I longed to take a second look at certain scenes to watch that insidious process at work. Isaacs desire for a wider audience is understandable, but the means by which he seeks it (fabricating or recreating scenes and dramatizing facts) are deplorable. Before I had a chance either to fully process that thought or see the film again, another, even more startling surprise gave me further cause to rethink it.

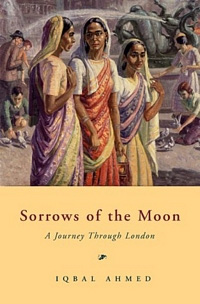

In her review of The Road in the March edition of Sight & Sound, Sophie Mayer mentioned Iqbal Ahmed's book Sorrows of the Moon: A Journey Through London (2004). I ran an independent bookshop in West Hampstead back then and had received an advance copy of that book. I'd read and relished it, then consigned it to the back of my mind and a box in the back of a cupboard. My memory awakened, I ferreted Sorrows of the Moon. I was immediately taken aback by another discovery: the author photograph in the book made it plain that Iqbal Ahmed, the writer, and Iqbal, the hotel porter, were, in fact, one and the same person. With the benefit of hindsight, it seems ridiculous that I had failed to make that connection earlier, but I'm certain I won't be alone in that. Iqbal's other life, as a gifted author, is nowhere mentioned in the film. Isaacs has, once again, been 'economical with the truth'.

A few days after finding my copy of Iqbal's book, I returned to The Tricycle for a screening of The Road and bumped into Keelta again in the cinema. During the Q&A that followed the film, MC Ian Haydn Smith invited her to the front. She perched herself on the lip of the stage, beneath the screen on which she'd recently appeared, then stunned all present by belting out a spine-tingling rendition of the Irish folk standard, 'Black is the Colour'. It is a ballad covered by Christy Moore, who sings his own song Cricklewood on the film's soundtrack.* Keelta's seemingly spontaneous performance was as memorable as many of those in the film, and equally pre-arranged.

I raised the matter of Iqbal's literary life with Isaacs, who was present for the Q&A. It seems he had contacted Iqbal after reading his book (a loosely autobiographical urban travelogue containing a series of immigrant stories) and that they had collaborated productively from then on. Having re-read Sorrows of the Moon, I'd go so far as to say that the book shaped the film as if it were a script. The publisher's puff on the book's front flap describes, "a displaced person" who "loses both lands – the one he flees and the one he adopts." The line is repeated, almost verbatim, in the film, just as the book's melancholic tone is replicated in it.

My first thought on making those additional connections was that Iqbal's story would, surely, have been at least as compelling if it had been told in the round, rather than forced to fit neatly into Isaacs' story of loneliness and loss. Much the same might be said of Birgitte's estranged husband Royston, who cuts a pathetic bed-ridden figure in the film, but actually spends half the year, every year, in Argentina. It would have been good to know that too. London, for most of its citizens, Iqbal and Royston included, is not the unrelentingly bleak and imprisoning place depicted in the film. And truth is stranger, and often more interesting, than fiction.

My second, more troubling thought, was: what exactly is 'true' and what 'false' in the film? Certain comments at The Tricycle Q&A – particularly one made by one of Isaacs' female researchers about Billy's death – intensified my sense of unease. She said she had alerted the police after becoming concerned for poor Billy's well-being, and that they had broken the door to his flat down subsequent to her call. It transpires that Isaacs was out of London at the time. And yet, Isaacs distinctly says, in the film, that he found the body. Let's be generous and call it a little white lie. Whatever we call it, it reveals much about Isaacs' tendency to toy with the truth – which, he never allows to get in the way of (his version of) a good story.

|

© Martin Gray |

It is a shame Iqbal Ahmed wasn't there for the Q&A. There were a number of questions I wanted to ask him about his work as a writer, about his role in the making of the film, and about his appearances in it. Above all, I wanted to know which scenes were fabricated and which, if any, were 'real'. Iqbal moved to London over a decade ago and has experienced a degree of success in the interim. At the time the Camden New Journal interviewed him about his second book, Empire of the Mind: A Journey Through Great Britain (2006), he was living in leafy Hampstead and writing on his laptop in the cafés of Camden. The film, however, presents him as a lonely recent arrival, lost in the city and trapped in low-paid work, reliant on dreams of Asia's appearance for his sense of hope and direction.

In one of the film's many staged set pieces, we watch a Skype conversation between Iqbal and Asia, in which he pours out his heart to her. His iPhone is propped up on a desk, her face glows from the phone – opposite her face in a framed photograph, and the scene plays out beneath a precisely positioned copy of Gabriel García Márquez's One Hundred Years of Solitude. The film would have been more honest, and more interesting, had the book so deliberately placed, face out, for us to see, been one of Iqbal's own.

Another sequence is edited so that Iqbal appears to gaze down, from a window in the Marriott Hotel where he works, at a Muslim rally taking place below, at the Marble Arch end of Edgware Road. Those familiar with the area's geography will know that to be an implausible view too far. Actually, Iqbal works at the Swiss Cottage Marriot, not the one on the A5 at Kilburn closer to Marble Arch, so it is even more geographically impossible than they might think. Like the scene involving Keelta's 'false start' at Holyhead and that revolving around the Skype conversation, it is a fabrication. The tragedy is that the engaging stories Isaacs records are enthralling enough to render embellishment as unnecessary as it is dubious.

Even those who argue that the ends (a good story) justify the means (bending the truth) must accept that audiences taking the film's claims to authenticity at face value are misled by such sleight of hand. Isaacs has said that he seeks out scenes for their 'dramatic impact'. He has argued that his resort to dramatic reconstruction reveals the 'greater truth' of things. I don't buy it. The Road, it seems to me, cloaks itself in the truth claims of documentary while creating a false and partial picture. It points to that loss of faith in fact which flows from our retreat from the political. It also highlights what John Corner called the crisis of confidence in the conventions of documentary, a crisis that continues to express itself in the inappropriate intrusion of entertainment and fiction values into non-narrative audio-visual forms (subjects I discussed here).

A decade has elapsed since John Corner wrote (in his essay Documentary in a Post Documentary Culture? A Note on Forms and their Functions) that 'factual entertainment', designed not to sugar the pill of hard facts but simply to attract larger audiences, had displaced three previously dominant projects: John Grierson's commitment to documentary as "an instrument of public thinking," journalism's role as a medium of enquiry and exposition, and the alternative perspective of an independent documentary film culture. The Road is the latest in a long line of films to fashionably blend fact and fiction in search of a wider audience – a tendency, it is worth noting, most pronounced in the portrayal of working-class lives.

Isaacs' style mirrors that of recent mock-documentaries such Carol Morley's Dreams of a Life (2011) and Clio Barnard's The Arbor (2010) – which, coincidentally, owed much to Jim Cartwright's play The Road. Morley's use of dramatic reconstructions marred her telling of the story of Joyce Vincent, the woman whose skeleton was found in her Wood Green flat three years after her death. Barnard's distracting use of theatrical reenactment detracted from her approach to the late playwright Andrea Dunbar's story. Like Morley and Barnard, Isaacs foregrounds drama and constructs fiction, at the expense of ideas and information.

This is not what Grierson had in mind when, speaking in an era when documentary was fused with a sense of social purpose, he minted the phrase: "the creative treatment of actuality." The three films mentioned above arose from, and speak of, a cynical culture in which lies – little, white, or whopping – are blithely accepted as a reality of modern life. The ubiquitous phrase, 'to be honest', of course, reveals how pervasive dishonesty is within contemporary public life.

It is hard to see where Marc Isaacs goes from here. No doubt he will continue to teach documentary filmmaking at the National Film & Television School, the London Film School, and Royal Holloway. Maybe he'll take the road travelled by the Dardenne brothers, Nick Broomfield, and others, and move to fiction filmmaking. Despite my reservations about The Road, I hope he remains loyal to documentary, rethinks his departure from its core values and forms, and continues his valuable work documenting the lives of immigrants, who now comprise the majority of London's population.

Isaacs could do worse than take a leaf out of Iqbal Ahmed's book. The Independent described Empires of the Mind as "an elegant epistle of disillusion." Ahmed's disillusionment related to his realization that Britain was not, as he had believed before his arrival here, the most civilized country in the world, the country where democracy and socialism worked most successfully. He was shocked to find a country with one of the world's largest prison populations, an island riddled with inequality, and a democracy decaying through disuse – in which barely half the electorate voted. His response was to document and describe his discoveries. He will find no shortage of material for further literary journeys. There is no shortage of material, either, for further films by Marc Isaacs.

|

© Martin Gray |

A tiny triangular traffic island at the Marble Arch end of Edgware Road marks the precise point where the A5 begins and ends. In the centre of that island, embedded in concrete as a fact on the ground, sits a small circular plaque marking the spot where, for centuries, public executions were conducted. It was the site of the grisly gallows of the 'Tyburn Tree' that sat at the centre of the sanguinary killing system known as 'the bloody code'. There, the code's victims were routinely and regularly hung, often 'drawn and quartered', before huge crowds. Most of the hanged were poor and marginalized people, a large proportion were recent immigrants, the majority were hung for property crimes not crimes against humanity.

The plaque, isolated as it is by the torrent of traffic, goes unnoticed – as many of London's immigrants do. For all its failings, The Road: A Story of Life & Death allows us to meet, if only briefly, a few of those in our midst, or once among us, who are generally bypassed by our culture; people we ourselves might have passed in the accelerated rush of London life. Isaacs may not have delved deeply into the immigrant experience, but he has provided us with a reminder that life is but a fleeting moment. He also, albeit inadvertently, reminds us that film is a transient form. In the introduction to his anthology of London writings, City of Disappearances, Iain Sinclair quotes from the late W.G. Sebald's essay Kafka Goes to the Movies: "Films," Sebald said, "far more than books, have a way of disappearing, not just from the market, but from memory, never to be seen again." And yet, there are people in Marc Isaacs’ flawed but often poignant film who will linger in the memory as long as any literary character.

Marc Isaacs' debut short, The Lift: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FJNAvyLCTik

Christie Moore's own composition, Cricklewood: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8hqAipVohbM

Forthcoming screenings of The Road: A Story of Life & Death:

19 March: The Riverside, Hammersmith.

24 March: Hackney Picturehouse

25 March: The Ritzy, Brixton

|