|

Part 2

"You will ask: But where are the lilacs/And the metaphysics petalled

with poppies/And the rain repeatedly spattering his words/filling them

with holes and birds?/Let me tell you what's happening with me . . .

oil flowed into spoons/a deep throbbing of feet and hands filled the streets

/metres, litres, the hard edges of life/heaps of fish/geometry of roofs . . .

And one morning it was all burning/and one morning bonfires sprang out

of the earth/devouring humans/and from then on fire/gunpowder from

then on/and from then on blood . . . You will ask: why doesn’t his poetry

speak to us of dreams/of leaves, of the great volcanoes of his native

land?/Come and see the blood in the streets/Come and see/The blood

in the streets/Come and see the blood/In the streets!" |

Pablo Neruda, from I Explain a Few Things |

I recently read the late Studs Terkel's autobiography Touch and Go. The great oral historian had much in common with Guzmán: each remained loyal to radical politics no matter how inconvenient, each suffered persecution during anti-democratic witch-hunts directed at the left (Guzmán in Chile under Pinochet, Turkel in the US under McCarthyism), both perfected the art of listening in order to record memory. In a chapter in Touch and Go headed, " . . . And Nobody Laughed," Terkel tells of a poll in which millions of US TV viewers had been asked to vote for 'America's greatest ever leader'. Among the candidates were Abraham Lincoln, Thomas Jefferson, Franklin D. Roosevelt and George Washington. And the winner is . . . Ronald Reagan! ". . . and nobody laughed." I'm uncertain whether Studs Terkel is suggesting that this is no laughing matter or that laughter, nervous laughter in this instance, is the only sane response to the debasement of politics and ignorance of history that poll result implies. Either way, it is frightening to consider what that says about the success of, and mass susceptibility to, propaganda. As Jefferson said: "If a nation expects to be ignorant and free, it wants what never was and never will be." In that same chapter of Touch and Go Studs Terkel presents other examples of wilful ignorance. On 15 February, 2006 the Chicago Tribune, Terkel's local paper, published an op-ed piece under the heading Iraq Needs A Pinochet. The author of the piece, Johan Goldberg says: "I think all patriotic and informed people can agree; it would be great if the US could find an Iraqi Augusto Pinochet." And nobody laughed. Although Pinochet died, in December 2006, before facing prosecution, he had already been indicted on criminal charges ranging from genocide and terrorism to torture and theft. And nobody laughed! Among the many charges Pinochet faced, and evaded, were several relating to the notorious Operation Condor and Caravan of Death cases investigated by Judge Juan Salvador Guzmán Tapia. Guzmán charged Pinochet following complaints presented by none other than the Mejeres de Calama (Women of Calama) and Victoria Saavedra, who appear in Nostalgia for the Light. Their unrelenting search for justice is inspirational. It is said that people get the governments they deserve. These indomitable women deserve a government that honours justice. In a 1995 speech, Pinochet said: "It is best to remain silent and to forget. It's the only thing to do. We must forget, and forgetting does not occur by opening cases, putting people in jail. FOR-GET, that's the word." And nobody laughed!

| The Parilla and Shock Treatment |

|

click to enlarge

The women Guzmán interviews in Nostalgia for the Light will not be silenced. They refuse to forget. British physician and author Dr Sheila Cassidy has not forgotten either. A softly-spoken, mild-mannered woman who chooses her words carefully, she has consistently spoken out about the crimes of the Pinochet regime. Her poise and equanimity lend an insistent force to the restrained anger with which she articulates her own grievances against Pinochet. When the dictator died she said simply: "I'm glad he's dead. He was an evil man." She had reason to say so. While practicing medicine in Chile in the 70's, she was arrested, interrogated and tortured by the DINA (Pinochet's secret police), after treating Nelson Gutierrez, a revolutionary on the run who had been shot in the legs. Unsurprisingly, her torturers found her compassion incomprehensible: "I told them I had attended Gutierrez because he was sick and that it wasn't in my code of behaviour to refuse attention to someone who needed help. They found this, frankly, too incredible to believe." In her book Audacity to Believe, she writes about the hell she lived through in Villa Grimaldi (the Pinochet regime's Lubyanka), and of her experience of the dreaded parilla (the barbeque) – one of the dictatorship's favourite torture techniques (readers of a sunny disposition might like to look away at this point). On several occasions she was blindfolded, stripped, and strapped down, naked and spreadeagled, on the iron frame of a bunk bed, before being subjected to what she calls, "repeated shock treatment." the application of electric shocks to her body by electrodes, which were occasionally inserted into her vagina.

The parilla was a practise so widespread, so efficiently and disgustingly barbarous, that it recalls the scientific cruelty of the Nazis. That may have been no accident. Paul Schäfer, the Nazi exile who, in 1961, had established the isolated German colony of Colonia Dignidad in Southern Chile, was an enthusiastic supporter of the coup. Now known as Villa Baviara/Bavaria, it was a secretive, sinister enclave surrounded by barbed wire and watchtowers, and served as one of Pinochet's many torture and execution centres. Josef Mengela is known to have visited the colony, but whether he passed on any of his deadly knowledge or not, Paul Schäfer and his followers certainly instructed DINA agents in the science of torture. Many of those tortured at Villa Baviara have recalled encountering the parilla there. Sheila Cassidy regards herself as "fortunate," in that she lived to tell the tale, but also because she escaped the additional pain inflicted on many detained women, who suffered the 'softening' preliminary humiliation of rape. Among the thousands similarly detained and tortured by right-wing dictatorships across Latin America were Chile's former President Michelle Bachelet (whose father, one of the generals who opposed the Pinochet coup, died in a prison), Uruguay's President José Mujica, and Brazil's President Dilma Rousseff. As a generation of former Marxist militants reached the end of what Daniel Cohn-Bendit called "The long march through the institutions," they used their positions of power to institute public enquiries into the past. Enquiries such as the ongoing Truth Commission inaugurated in Brazil by Dilma Rouseff testify to that hopeful adage, 'The truth will out'.

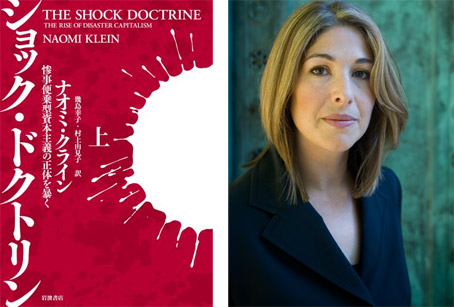

I mention Sheila Cassidy's appalling experience in the hope that recalling a compatriot's suffering will, in some minute way, bring home the unspeakable cruelty of Latin American fascism, but also to introduce the analogy Naomi Klein draws between torture and laissez-faire economics in her 2007 book The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. Klein persuasively, if tendentiously traces connections between the CIA-funded experiments in electroshock therapy conducted by Ewan Cameron in the 1950s (part of mind control research but, Klein claims, also used to develop techniques of psychological torture), modern 'shock and awe' military strategies (the use of spectacular force to disorientate and cow an enemy), and the use of economic 'shock treatment' (proposed by Milton Friedman soon after 'The Nixon Shock' that ended the Bretton Woods Agreement, road-tested in Chile after the Pinochet coup, and enthusiastically endorsed, adopted and adapted by the Thatcher-Reagan axis). In their film adaptation of Klein's bestseller, The Shock Doctrine (2009), Michael Winterbottom and Mat Whitecross update Klein's hypotheses about state terrorism and neoliberalism to include notes on the current crisis of Capitalism. Using footage from The First Year and The Battle of Chile, the film boils the book down to its basics to create a punchy narrative about how history has unfolded since the coup. Klein, Winterbottom and Whitecross provide an invaluable aide-mémoir while showing how the hit-em-fast, hit-em-hard tactics they describe works to wipe out collective memory. As Mat Whitecross, whose parents were tortured by Argentina's dictatorship in the 70s, says: "The Shock Doctrine is not simply a history lesson, but also a prism through which to interpret the world. We have to educate ourselves about the past to understand how we can shape the future."

Naomi Klein's argument about Allende, Pinochet and Chile largely cover old ground. The lengths to which Nixon, Kissinger, and the CIA went to sabotage Chile's democratic revolution have been well documented, but nowhere more impressively than by Hugh O'Shaughnessy in his book Pinochet: The Politics of Torture, Peter Kornbluh's book The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability, and Patricio Guzman in The Battle of Chile (Part 1: La insurrección de la burguesia/The Insurrection of the Bourgeoisie, Part 11: El golpe de estado/The Coup d'état). Klein points out that the Pinochet bloodbath was born in the USA and pinpoints 11 September 1973 as one of pivotal moments of contemporary history, a turning point of the 20th century to rank alongside, say, Kronstadt 1921, Budapest 1956 and Prague 1968. Soviet tanks and Chilean tanks, Brezhnev and Dubcek, Pinochet and Allende; the parallels could not be more obvious, the stakes could not have been higher. The unhinged hatred Pinochet, Nixon, Kinsinger and their kind felt for Allende was rooted in a fear of democratic socialism, that solidified during the Cold War and had been intensified by McCarthyism. Although the post-war Attlee government in the U.K had demonstrated that democracy and socialism were compatible, this idea must not be allowed to flourish in Latin America. As Seymour Hersh says, what panicked Kissinger most was not Allende's electoral success alone, but the thought that 'the political process would work and he would be voted out of office in the next election." The prevailing idea that capitalism and democracy are indivisible was first established. It was in Chile, too, that free-market fundamentalists launched their international attack on social democracy and the welfare state.

Naomi Klein coolly describes the ways in which the ideas of Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek were planted in Chilean soil rendered 'clean of 'impurities', as Hayek put it, by the Pinochet junta. After violently neutralizing the political left, prohibiting freedom of speech, and destroying democratic pluralism, Pinochet rolled out a blood red carpet for Friedman's disciples. In moved the Chicago Boys, the shock troops of neo-liberalism, to enthusiastically apply monetarist shock treatment; the privatization of publicly-owned industries and public services, the extension of cheap credit to cover falling wages, reduction of the money supply, and so on. Klein presents impressive evidence of how the ideology of neo-liberalism was imposed on Chile under conditions created by neo-fascism. She puts the cat among the pigeons by presenting the Chilean experience, essentially, as a dress rehearsal for all that followed in the Thatcher-Reagan era, even for the occupation of Iraq. Klein also highlights state terrorism, suggesting that the implementation of aggressive free-market reforms has consistently been, deliberately and of necessity, bound up with torture and political repression. She argues that human rights activists have too often ignored political context, thus presenting examples of torture as aimless, inexplicable and random episodes of human cruelty.

Here, as elsewhere, Klein echoes the arguments presented by Orlando Letelier in his telling 1976 article for The Nation, The Chicago Boys in Chile: Economic Freedom's Awful Toll.* Letelier, who served as Allende's US Ambassador and held various ministerial porfolios in the Popular Unity government, wrote: " . . . the necessary connection between economic policy and its sociopolitical setting appears to be absent from many analyses of the current situation in Chile. To put it briefly, the violation of human rights, the system of institutionalized brutality, the drastic control and suppression of every form of meaningful dissent, is discussed (and often condemned) as a phenomenon only indirectly linked, or indeed entirely unrelated, to the classical unrestrained free market policies that have been enforced by the military junta . . . This particularly convenient concept of a social system in which economic freedom and political terror coexist without touching each other, allows . . . financial spokesmen to support their concept of freedom while exercising their verbal muscles in defense of human rights." He continues: "The economic plan now being carried out in Chile realizes an historic aspiration of a group of Chilean economists, most of them trained at Chicago University by Milton Friedman and Arnold Harberger. Deeply involved in the preparation of the coup, the Chicago Boys . . . convinced the generals that they were prepared to supplement the brutality, which the military possessed, with the intellectual assets it lacked . . . The inhuman conditions under which a high percentage of the Chilean population (now) lives is reflected most dramatically by substantial increases in malnutrition, infant mortality and the appearance of thousands of beggars on the streets of Chilean cities. It forms a picture of hunger and deprivation never seen before in Chile." Letelier ends on an optimistic note: "Between 1970 and 1973, the working classes had access to food and clothing, to health care, housing and education to an extent unknown before. These achievements were never threatened or diminished, even during the most difficult and dramatic moments of the government's last year in power. The priorities that Popular Unity had established in its programme of social transformations were largely reached. The broad masses of the Chilean people will never forget it." Orlando Letelier was assassinated in Washington by DINA agents acting under Pinochet's orders, a few weeks after writing those words and just a week after Kissinger rescinded a diplomatic demarché protesting Operation Condor, the murderous campaign of state terrorism that cost the lives of tens of thousand across Latin America.

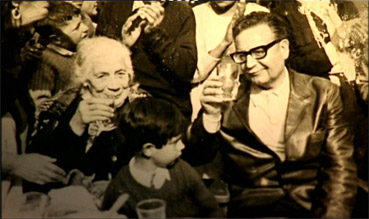

When Pinochet died Margaret Thatcher was reported to be "greatly saddened' by the news of the dictator's death. No surprise there; Thatcher and Pinochet were always thick as thieves. They had a lot in common: Pinochet had scrapped the rations of milk the Allende government had dispensed to children of the poor, Thatcher did away with the free milk provided in schools for children over seven years-old; Pinochet advised her that the first thing she should do after unpacking in No 10 Downing Street was dismantle public housing, Thatcher duly inaugurated the 'right-to-buy' policy; Pinochet and the Chicago Boys set about reversing the nationalizations of the Allende government, Thatcher set about reversing the nationalizations of the Attlee government. When Pinochet was arrested in London in 1998, after Judge Baltasar Garzón issued extradition proceedings against him from Madrid, the Chilean despot, was accommodated, in luxury and 'at taxpayers expense', at a country house, where he took tea with his fellow milk snatcher. Thatcher, naturally, complained about Pinochet's arrest, calling it "gesture politics." Alan Bennett replied, with characteristic wit, that her defence of Pinochet was itself an example of gesture politics, "the gesture in question being two fingers to humanity." Clearly chuffed to have her chum to stay, Thatcher praised Pinochet's resilience and fighting spirit, but, in the wink of an eye the general's fortitude deserted him and he was, fortuitously, deemed too ill and senile to face justice. Thatcher, of course, had evaded the court of public opinion herself in 1990, having been removed from office by her own admirers before the British electorate had a chance to do so. Never noted for lachrymose behaviour, the Iron Lady left No 10 in tears, deeply wounded at being disloyally deselected by her Tory colleagues. Her feelings of betrayal were, presumably, similar to those felt by Salvador Allende when he read Pinochet's name atop the junta's ultimatum demanding his resignation. Allende, who had gone out of his way to secure the military's loyalty to democracy and who had trusted Pinochet up to end, simply said: "Poor Pinochet. He's been captured." The capture of Pinochet by the courts is brilliantly recounted in The Pinochet Case. Guzmán's film provides vital evidence that should inform the verdict of history on Pinochet.

Meanwhile, where Thatcher and Reagan are concerned, the jury is out, but edging ever closer to another unanimous guilty verdict. It is becoming widely accepted that we are now reaping the whirlwind of the discredited, debt-driven free-market economic model of the Thatcher-Reagan era. Thatcherism's Big Bang of 1986 deregulated the markets, unleashed an unmuzzled culture of greed that still dominates public life, and ushered in the spectacular levels of indebtedness that underpinned 'the credit crunch' and lead inexorably to the collapse the banking system. The gung-ho privatisations of the last 25 years transferred public wealth (that of the many) into private hands (those of the few) on an unprecedented scale, then, after decades of being lectured about 'lame duck industries' and the supposed perils of public intervention in private economic affairs, we witnessed a reverse flow of money, as public wealth was pumped into private banks to rescue them.

As I wrote the words above, my local postman popped a copy of the London Review of Books through my letterbox. It was a serendipitous delivery. In this issue, dated 13 September 2012, James Meek provides a detailed and damning assessment of the consequences of electricity privatisation which works as a useful metaphor for the Thatcher-Reagan era and highlights where, and how, political power lies. Meek says: "Defending her record in parliament on the day she resigned in 1990, Thatcher spoke in patriotic tones of how, with millions of people buying shares in former state industries, privatisation was giving 'power back to the people . . . Now, in 2012, it's clear that the result of electricity privatisation was to take power away from the people. Small British shareholders have no influence over the overwhelmingly non-British owners of the firms that generate and distribute power in Britain . . . The most unexpected consequence of selling the country's electricity legacy, the consequence that most directly contradicts what the Thatcherites were trying to do, was the gradual absorption of swathes of the industry by (publicly-owned French company) EDF . . . France, in effect, renationalised the industry its neighbour had privatised. Renationalised it, that is, for France." The power not with France, not with any nation state, but with multinationals like EDF, which is only nominally publicly-and-French-owned.

Interestingly, Meek also tells us, in passing, that Spanish economist Germà Bel has traced the origins of the word 'privatisation' to the german Reprivatisierung, "first used in English in 1936 by the Berlin correspondent of the Economist, writing about Nazi economic policy," and that the word first appeared in academic literature "in 1943, in an analysis of Hitler's programme in the Quarterly Journal of Economics." Concluding his etymological aside, Meek adds: "The author (of the Q.J.E. piece), Sidney Merlin, wrote that the Nazi Party, 'facilitates the accumulation of private fortunes and industrial empires by its foremost members and collaborators, through 'privatisation' and other measures.' I'm sure my local postie and his colleagues would find that interesting too. After all, they work for Royal Mail, a cherished public service currently being run down in preparation for privatization. In Dear Granny Smith, an anonymous postman calling himself 'Roy Mayall' provides a worker's view of moves afoot in his industry: ''Modernisation' means scaling back the service in order to serve the interests of the corporations. It means 'profitability', which means 'cutting costs', which means 'cutting back on fixed expenditures', which means – and I don't have to employ inverted commas for this – lower standards and lower wages."

Lower wages from some, astronomical bonuses for others, but, hey, you might say, everybody knows capitalism equals inequality, most people dislike it but they're resigned to it. Myself, I wonder how often people actually stop to consider the matter, to really think about it, to picture it. Isn't the acceptance of that unpleasant reality not always accompanied by a shrug of the shoulder that absolves the shrugger or all responsibility? And isn't the shrug of cynicism preconditioned by the apparent absence of an alternative? Be that as it may, I was startled, if not shocked, to learn from The Shock Doctrine that, "In Britain before Thatcher a CEO earned more than ten times the average worker. By 2007, they earned more than a hundred times as much. In the US before Reagan, CEOs earned 43 times as much as the average worker. By 2005, they earned more than 400 times as much." Researching the ALMA astronomy installation for this article, I stumbled upon an article in the Wealth Matters section of the New York Times about the pressing problem of hereditary wealth, in particular, the uncommon problem of 'What to Tell the Children About Their Inheritance and When'. The author of the piece, Paul Sullivan, says that when Naomi Sobel learned – at 20 years-old – that she was about to inherit wealth, she wondered if it would be enough to buy a house. Was it enough? It was: "She laughs at this today, since it would have paid for many, many houses." As Studs Terkel might have said, it's no laughing matter. According to a 2010 report on 'intergenerational transfers' by Metlife, 'The Mature Market Institute', 'Baby Boomers' in the US stand to inherit S8.4 trillion from their parents, rising to $11.8 trillion when inter vovos gifts are taken into account. According to a 2112 report by Accenture's 'Wealth and Asset Management Services' team, 'Boomers' will leave $30 trillion to their offspring over the next three or four decades. Sullivan refers us to another piece he wrote about inequality, in which he writes about the legislation, soon to expire, enabling rich Americans the chance to give over $5 million to their offspring, without paying tax. In that article, To Give or Not to Give, Sullivan bemoans the tough choices the super-rich face: "Do they give their heirs the full amount of the exemption . . . or do they give less, or none at all, for fear that they could be left without enough to live on?" Fortunately for them, " . . . that gift (of $5 million) could have grown in 30 years to nearly $29 million . . . Meanwhile, the parents' estate would have been reduced by $29 million, cutting the tax due on the estate." So, everybody's happy then – apart from the majority of us that is, those of us who have to earn a living.

The Accenture report cited above, and subtitled 'Capitalizing on the Intergenerational Shift in Wealth', makes uncomfortable reading for those of us who, stubborn mules that we are, persist in believing that fairness and the redistribution of wealth are more inextricably linked than democracy and capitalism. The philosopher Francis Bacon said: "Money is like muck, not good except it be spread." Bacon's adage calls to mind that quaint North Country truism, 'Where there's muck, there's brass'. Most Chileans know what hard, dirty work is, so they'd doubtless agree, but those of a certain vintage might prefer to say, 'Where there's brass (and copper), there's muck (and blood)." Chile is the world's largest producer of copper and copper is the country's economic lifeblood. As a country rich in natural resources, Chile has historically received more than its fair share of unwanted attention from predatory outsiders, and much less than its fair share of the material wealth it possesses. Salvador Allende's Popular Unity government was determined to change that. When Allende nationalised the copper companies, in 1971, he carved 'excess profits' (anything over 12 per cent of a company's value) off the compensation payments made to foreign mining interests such as Anglo-American, Anaconda, and Kennecott. The move terrified Washington, which feared copycat expropriations across Latin America as much as it did the sound of falling dominoes. The CIA's destabilization campaign in Chile was immediately ratcheted up several notches.

After the Pinochet coup, the Chicago Boys, of course, 'reprivatised' the copper industry and let the wolves back in, they 're-opened the door to inward investment' to use the doublespeak of our times. As Chilean journalist Roberto Navarrete says in Red Pepper magazine: "Codelco, the state-controlled copper mining company, now controls only 30 per cent of copper production in Chile; foreign companies account for most of the rest." Last year miners working for Codelco went on strike to protect their pay and conditions. They pointedly struck on the 40th Anniversary of Allende's nationalization of the mining industry. A spokesman for the Miners' Union accused President Sebastian Piñera's right-wing government of "preparing the ground for privatization." The BBC reported that Piñera had installed new management in order to cut costs and modernize the company. Robert Navarette points to the chief beneficiary of the shift back to foreign ownership of the mines, none other than Sebastian Piñera, "one of Chile's richest people (and) the closest the country has to Italy's Silvio Berlusconi. Piñera's fortune, estimated by Forbes at more than US$1 billion, was amassed during the Pinochet dictatorship, when his brother and former business partner, Jose Piñera, a Labour minister under Pinochet, was the one who reformed the mining law, opening the mineral sector to private investment . . . Sebastian Piñera's business group owns stakes in several major Chilean companies in the energy, mining and retail sectors; it has 100 per cent control of Chilevision, a terrestrial TV channel; owns the largest airline in South America, Lan Chile; and owns the country's most popular football team, Colo-Colo." Let's call it a case of 'capitalizing on the intergenerational shift in wealth'.

As Hugh Trevor-Roper says in his book History and Imagination: "History is not merely what happened; it is what happened in the context of what might have happened." The Battle of Chile exists as a reminder of how wealth and power has shifted since the Allende years, it serves as a document of historic events, but, perhaps more importantly, it also stands as a challenge to our times and a monument to the people of Chile in their finest hour. The film's radicalism and realism may be unfashionable, but it remains one of the greatest political films ever made. I've watched Part III, El podar popular/The Power of the People, more often than I can recall. It never fails to amaze me. It always moves me to tears. I can think of no film that more completely captures the energy, enthusiasm, intelligence, inventiveness and resilience of a people attempting to shape history. It records the hope and optimism, the sense of solidarity and strength, the sheer joy, with which the best of Chileans squared up to the worst of Chileans and faced down what Orlando Letelier called, "the most destructive and sophisticated conspiracy in Latin American history." The Battle of Chile contains moments that recall the lyricism of Humphrey Jennings' wartime documentaries, there times when it is reminiscent of Godard's commitment and Rosselini's compassion, and others when it reminds us of Chris Marker's grasp of the sweep of history, but, ridiculously, the film it reminds me of most often is Christopher Morahan's delightful comedy, Clockwise (1986). Before you think I've lost the plot, I should explain that it reminds me of one line from Morahan's film in particular, the line spoken by Brian Stimpson as played by John Cleese: "It's not the despair Laura, I can take the despair, It's the hope I can't stand." It is a memorable line; it's pithy, it's bewitching, it rings true, but it's false, it's wrong.

Although it bears Guzmán's unmistakable creative thumbprints, The Battle of Chile was a collective effort. In the same New Yorker review of the film cited above, Pauline Kael asked: "How could a team of five – some with no previous film experience – working with limited equipment (one Éclair camera, one Nagra sound recorder, two vehicles) and a package of black-and-white film stock sent to them by the French documentarian Chris Marker, produce a work of this magnitude? The answer has to be, partly at least: through Marxist discipline. The young Chilean director, Patricio Guzmán, and his associates had a sense of purpose. They were a collective, and they were making a work of political analysis." Looking back at the Chilean revolution across four decades, it's natural to feel demoralized. The phrase 'Marxist discipline' has been drained of meaning, robbed of its force by destructive storm surges of human design. Allende is dead. Kael is dead. Marker is dead. We mourn them. But hope lives on. La esperanza muere última. Hope dies last. The opening line of Studs Terkel's book Hope Dies Last is: "Hope has never trickled down. It has always sprung up." He interviews Roberta Lynch, a Chicago labour organizer, who says: "You feel that things can happen, the possibility, the hope. You feel ordinary people can do extraordinary things. Something comes along unexpectedly, something no one could have predicted." The ordinary people of Chile made things happen; they did extraordinary things; thousands of them died doing so. The Battle of Chile and Nostalgia for the Light, Patricio Guzmán's entire work and life, remind us of events, ideas, people, possibilities and hopes that power would have us forget.

< Part 1

* Orlando Letelier's article on the Chicago Boys in The Nation: http://www.ditext.com/letelier/chicago.html

The Nobel-Prize-winning Chilean poet Pablo Neruda died, some say of a broken heart, shortly after the Pinochet coup, on 23 September 1973. Here, Neruda reads from his poem I Explain a Few Things. The poem is about the Spanish Civil War, and his grief at the death of his friend, the great Spanish poet Federico García Lorca, who was murdered by Fascists. It can stand in for things Neruda might have said about the Chilean revolution and his friend Salvador Allende.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=34IkFe9v3xw

|