|

It's funny how parochial we can get when it comes to filmmakers and the countries in which they live and work. We tend to expect, for example, that a French film featuring French actors and dialogue will have been made by a French director. There's a logic to this, as writer-directors in particular tend to draw on what they know when shaping stories or defining characters, and making films in your own language is tough enough without the added problem of having to go through an interpreter to converse with your cast and crew. The one place this doesn't seem to matter is Hollywood, whose budgets and hunger for any new talent has prompted on-the-rise filmmakers from all over the world to abandon their home turf and make American stories for worldwide consumption. Oddly enough, it rarely happens the other way around. Precious few American directors have nipped off to Europe to make films in a language in which they are not fluent, unless this is counterbalanced by the presence of an American star or two to struggle with local customs and translate the plot points for us. When they have gone the whole hog the results are sometimes startling – witness Paul Schrader's stunning Mishima or Julian Schnabel's remarkable The Diving Bell and the Butterfly if you're looking for evidence.

It's perhaps this almost subconscious preconception that sent my eyebrows skyward when I first heard that acclaimed Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami had made a film in Tokyo in the Japanese language with an all-Japanese cast. But why in hell not? I have little doubt that my surprise stems from the distinctive nature of Iranian cinema, which tends to tell recognisably Iranian stories, albeit ones underscored by more universal themes. But word has it that Kiarostami has had a long standing fascination for Japanese culture (I'm with him on that) and he even composes his own haiku-like poems, and given the restrictions imposed on any filmmaker currently working in Iran (and let's not forget what happened to his contemporary Jafar Panahi – look him up if this one has somehow escaped your attention), such a location shift does offer him a freedom that he would be denied on home turf.* And there's certainly an element or two of his latest, the intriguingly titled Like Someone in Love, that would probably fall foul of the Iranian Ministry of Guidance.

The film opens on a static wide shot of a busy Tokyo café bar interior at night, where our eyes are drawn to no-one in particular. The voice of an unseen female can be clearly heard assuring an inaudible third party – by phone we presume – that she really is in the Café Theo with her friend Nagisa. To add weight to her claim, a cheerful young woman sitting closer to the camera than the other patrons moves into the foreground and takes the phone from her friend to assure whoever it is at the other end of the line that the pair are indeed at the Café Theo. At this point we have reason to suspect this is untrue. By now the camera angle has reversed to reveal Akiko, the owner of the previouslt disembodied voice, and I start to worry about how much of what subsequently unfolds I should give away here. It's not that what follows contains any startling twists – this is a Kiarostami film after all, not House of Games – but because one of the principal pleasures of how story here unfolds is the manner in which its jigsaw puzzle of story and character detail gradually comes together to form a clearer picture of exactly what is transpiring. Thus if you want to get the most from your first viewing of the film and have not already read about it, then I'd skip to the last paragraph and go see it instead, as everything from here on will act as a minor spoiler to this intriguingly handled slow reveal.

That Akiko is working part-time as a prostitute is something all but the most innocent viewer should be able to suss long before she arrives at the apartment of her latest client, the elderly writer and translator Watanabe Takashi, a man held in high regard by Akiko's persistent and persuasive middle-aged pimp. Her taxi ride there an increasingly emotional journey, as she cycles through the messages left by her visiting grandmother, who remains hopeful to the last that her granddaughter will be able to find time to meet up with her before she heads back home. What initially played like an excuse offered to both her fiancé Noriaki and her disbelieving pimp proves to be a cause of real regret on Akiko's part, as she has the taxi driver circle the station concourse at which it was last suggested the two meet and tearfully catches sight of her waiting and still hopeful grandmother. In this one short and cinematically straightforward sequence, Kiarostami emotionally bonds us to Akiko with an economy that almost qualifies as sleight-of-hand.

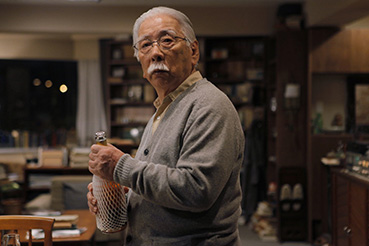

Then, shortly after her arrival at Takashi's apartment, the unexpected happens and in the space of a just couple of minutes our sympathy shifts from Akiko to Takashi, a kindly old man who has clearly hired Akiko for companionship rather than sex, a lonely widower who requires of this young girl no more than conversation and dinner. Akiko, however, is oblivious to his wants, and in a self-absorbed combination of professional auto-pilot and extreme tiredness, slips into her night-gear and trots off to the bedroom, where her once again disembodied voice dismisses Takashi's polite requests that she return to the living room and join him for dinner.

Such strong and rapid connection with character is down to the captivating realism of the two lead performances and the patient and unobtrusive subtlety of Kiarostami's direction. The two actors in particular are quietly superb, from Takanashi Rin's mounting unhappiness as Akiko during the above-detailed taxi ride to Okuno Tadashi's convincing and moving naturalism as the lonely Takashi, who on being denied the evening of companionship he had longed for, wanders sadly around his living room (Okuno's body language in this sequence tells a story in itself) and disconnects the phone so it will not wake the now soundly sleeping Akiko.

Save for a key sequence in the later stages, it's with Takashi we stay for the remainder of the film, as his concern for Akiko's well-being prompts him to act in an almost fatherly manner towards her, driving her to the school at which he used to teach so that she can sit an exam and offering to buy her lunch out of nothing more than concern that she has not eaten.** Twice he mistaken for her grandfather, once by a nosey neighbour and once by Noriaki, whose curious observation of Takashi's waiting car and eventual approach is leant a layer of real tension by both his aggressive behaviour towards Akiko (which is observed entirely from the nervous Takashi's viewpoint) and our concerns over how he would likely react on discovering the truth of her relationship with this frail old man.

In spite of the location and cultural shift, Kiarostami's cinematic signature is clearly evident throughout, from his use of initially disembodied voices to his fascination with character, situation and the music and detail of conversation (much of which takes place in cars, which itself has become something of a Kiarostami trademark). There is also a sense that we're not watching a complete story but a small detail from one, subjective experience examined with the patient fascination and probing curiosity of a budding sociologist with a degree in anthropology. Whole sequences are allowed play out in real time and frequently include elements that almost every other filmmakers would instinctively trim but which prove both strangely hypnotic and suggestively revealing, as when Takashi drifts off to sleep in stationary traffic, or his nervous observation of the argument taking place between Akiko and Noriaki, one that prompts him to unbuckle his seatbelt ready for action that he clearly does not have the self-assurance to take.

Just as open to speculation is the root of Takashi's protective affection for Akiko – is his interest in her purely paternal, the result of an unspoken kinship, or does she remind him of his late wife? – and I've already encountered one on-line discussion around what is implied by the earring that Takashi finds unexpectedly in his living room bedclothes on the morning after Akiko's first visit. But it's the startling and abrupt ending that has fired the most debate, one that would be tactless of me to contribute to in detail here, save for the observation that it both literally and metaphorically shatters the protective veil of deception behind which both Takashi and Akiko have until then been hiding.

It seems unlikely that the film's unhurried pacing, long-held shots, lack of action and story-twisting incident and seemingly slender narrative will win too many converts to the Kiarostami style. But for those more sympathetic to this singular filmmaker's approach, Like Someone in Love represents a captivating cultural diversion, a moving and acutely observed study of loneliness and the gap that lies between who we really are and the image that judgemental convention encourages us to publicly project. As the product of an Iranian filmmaker working in Tokyo, the film never feels the result of an outsider looking in and I was left with the very real sense that, cinematically and dramatically speaking, Kiarostami really has found a second home here.

* It should be noted that this not Kiarostami's first non-Iranian feature, as those who admired his 2010 Certified Copy / Copie conforme, which starred Juliette Binoche and William Shimell, will be well aware.

** The issue of Japanese schoolgirls who moonlight as prostitutes, often to raise money to buy the latest fashionable goods, is a long-standing one and was even the subject for Harada Masato's 1997 feature Bounce Ko Gals / Baunsu ko gaurusu

|