"The nineties was the true era of alternative music." |

Melissa Auf der Maur, ex-bassist, Hole/Smashing Pumpkins |

Somewhere in the south of France in the Summer of '91, a month after Hole released their debut album Pretty on the Inside, my cousin and I, not yet double-figured in years, but undoubtedly the most rock n' roll pair of eight-year olds you're ever likely to meet, were searching for our next Marshall-amplified fix. Back then, the cooler parents exploded prepubescent minds with the rule Britannia riffs of The Stones or The Who, but ours was an upbringing of regional southern rock. Reared on the guitar-cowboy virtuosity of Lynyrd Skynyrd, Molly Hatchet, ZZ Top and 38 Special, it was the swampland solos of the South, which inspired us to take up our tennis racquets and express our admiration through gurning-faced mime. In awe of their engine-rev kick and mountain-scaling notes (be they wrenched or teased), we sought to find a band with the same brand of fiery fretwork we could truly call our own.

It was right around that time that Appetite for Destruction changed everything, and Guns N' Roses single-handedly put an abrupt end to any illusions of eight-year-old innocence. Taking the lyrics very much at face value, the references to heroin went right over my head. For years I believed "Mr Brownstone" was a curmudgeonly neighbor irked by the band's all-night parties, never once occurring to me that he was in actual fact, the band's dealer. Young enough to misconstrue many of the lyrics, the virile menace, sexuality and danger of the music was plainly undeniable, every spin of that brand new compact disc like the handling of illicit contraband. And so that Summer, with pocket money saved, and excitement barely contained, we drove from our campsite to the town's nearest supermarket and bought both parts of the ambitiously epic, double album follow-up. I scored Use Your Illusion II, (the better of the two), my cousin got Use Your Illusion I. Long before the era of illegal downloading, we stole what we couldn't afford by shoplifting the covers of both albums from our local Our Price and then copying each of the original tapes so that we could both own legitimate-looking copies of the full thirty song opus. I blame my cousin for my juvenescent bout of kleptomania, He still blames Axel Rose.

So how does any of this relate to Hit So Hard, the band at its center and the women on skins? Well, it was on that same auspicious shopping trip that my father decided one life-changing record wouldn't suffice, picking-up both Extreme's Pornographfitti (still my all-time favourite "guitar" record) and an album with a submerged naked baby swimming after a fish-hooked dollar bill on the cover. The iconic sleeve image of Nirvarna's Nevermind went on to visually represent the birth of grunge, but to two unassuming eight-year-olds it was simply the third best album we bought that afternoon, in an age where it seemed as though masterpieces were being released on a bi-weekly basis. Auf der Maur calling the nineties the true era of alternative music got an approving nod from me as I thought back over all the bands for whom Cobain's crew paved the way. Though far be it for me to call him singularly responsible; outside of the grunge explosion, change was everywhere, Metallica took metal to arena-sized audiences with their self-titled "Black Album" while Pantera's Vulgar Display of Power and Machine Head's Burn My Eyes are still rightly regarded today as gold standard envelope-pushers in the evolution of extreme heaviness. With so many seminal works being released in seemingly infinite succession, the alternative music explosion of '91 to '96 was in the ether, the tissue of the times.

Of course Nevermind rocked my world like everyone else and of the three, I suppose it was the album that best defined that Summer, though I'm talking purely of nostalgic memory here, being completely unaware of the wider cultural shockwave as it was happening. How I remember it, "Smells Like Teen Spirit" was just another video that MTV was playing in heavy rotation with "Enter Sandman" at the time. So until history caught up with me and told me otherwise in my teens, Nevermind was simply a gateway drug to who this writer considers far greater grunge outfits such as Smashing Pumpkins, Alice in Chains, Soundgarden and Pearl Jam. If it wasn't plaid-clad anthems I was blasting darker, heavier fare: Metallica, Megadeth and Faith No More (whose keyboard player Roddy Bottum is a featured talking head here), and for middle-fingered, funked-up snotty impertinence, I went straight to Ugly Kid Joe, so Hole's unbridled brand of female bile completely past me by on the first go around. As musically open-minded as I believed myself to be back then, at that age, you're in an emotional wind tunnel, not caring to take time out for albums that don't appear to directly reflect or shape the experience of your formative years. I suspect that had I been more aware of Hole, the shift of gender perspective would have rendered the reasons behind the rage unintelligible. It was only later, when Auf der Maur left Hole to join the Smashing Pumpkins, and subsequently learning that Billy Corgan once dated Courtney Love, that I became fully aware of The People Vs Larry Flynt star's day job as a punk rock front woman.

And sure, while they've got some memorably charged angsty refrains ("Violet", "Jennifer's Body") and some angular, jump-up-and-down, punchy riffs ("Plump"), Hole just never grabbed me in the same way as any of the aforementioned, despite their indelible impact on a male-dominated playing field. The face of Hole always seemed infinitely more interesting and volatile than the tunes and if Courtney Love's drunk and disorderly hot mess feminism had a compelling unpredictability and human car-wreck fascination that sent many a song off the rails when playing live, filmmaker P. David Ebersole goes out of his way to let us all know how much harder it was on Patty Schemel than most drummers to lay down a steady beat – harder still when you're drugged up to your eyeballs on a cocktail of heroin, crack and booze.

Born to alcoholic parents, Schemel and her brother were practically twins and did everything together, including coke and speed from a very early age, which isn't specified. This is the first instance of many where Ebersole betrays a curious disregard for important detail, showing his hand just as quickly by not pointing the finger of blame at any of the parties most likely responsible for these early transgressions. Pre-occupied with framing this account of unlikely survival as a tale of (questionable) triumph, hard-line investigate reporting goes out the window in favour of a positive family portrait. Schemel's mother crops up regularly but never once is she asked outright about her awareness of her daughter's drug abuse during high school, how that made her feel as a parent or what she did/might have done to curb it. Nor does Ebersole fire any warning shots by posing the dangling question of hereditary addiction. Editorially, this kid gloves treatment feels suspect from the off – no surprise then to learn that Ebersole and Schemel are personal friends.

From the moment she was playing drums in the high school cafeteria Schemel was routinely drunk and getting kicked out of bands was her MO. Looking back from a sober perspective, the musician's candor on the destructive impulses of her youth makes her an engaging subject, though her epigrammatic summations of troubled times, suggest easy-going concealment of unspeakable larger evils. Discussing her darkest hours, Schemel almost seems too comfortable, as if she senses the filmmaker's softball approach poses no threat. Ebersole never comes close to penetrating the possible smokescreen or backing the drummer into a corner with tough questions, because he's too busy setting up segue ways; lending his subject's pithy responses inordinate significance for detours down socio/historical side streets.

Hole guitarist Eric Erlandson was the band's designated driver when the others partied hard and often. His clear-eyed impression at the time was a nascent scene smothered under a black veil of lethal narcotics: "Kurt's death flung the curtains open on a scene rife with hard drug taking and nobody liked seeing the demons." Ebersole is keen to persuade us that such dangerous hedonism was a subconscious protest of the powers in government, implausible as it is, that a drug-addled musician's under-the-influence field of vision would make room for – much less consider – big picture political consciousness. The notion of reckless rock star behaviour and the dark sounds it inspired as a vicarious product of the age of "mutually assured destruction" certainly intrigues, but if grunge is in part a reaction to the finger hovering over the button, and an un-relatable, previous generation personified by untrustworthy Presidents (Bush and Reagan), the lack of supporting testimony from any of the doc's major players makes only a tenuous connection at best.

The scattershot assemblage of talking point topics (the niche of female drummers in the industry, Schemel's lesbianism) are irreverently smashed together and skipped over in a teal and mauve Hi-8 blend of circa '94 MTV transitions, intended to visually conjure the era, which merely underlines the film's shapeless structure. Continually shifting the focus in Reality Bites-sized chunks, Schemel never holds court in her own story and the film would have greatly benefited from anchoring its attention on the impossibility of staying sober whilst living the rock and roll lifestyle. The strewn pieces of Schemel's story often horrify but without a clear emotional through line, never engender our sympathies as they should.

|

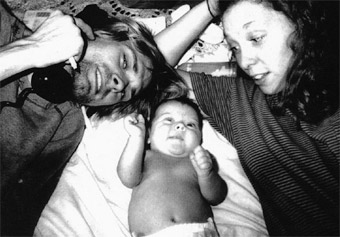

The classic Hole line-up, reunited for the first time

in thirteen years at the film’s premiere. |

Seeing this in the context of the BFI Lesbian & Gay Film Festival, the film's cursory treatment of Schemel's sexuality was especially disappointing. While the film's biggest laugh comes off the back of lesbian folksinger Phran's observation that the inspiration behind the '90s grunge look was a straight rip-off of lesbian fashion from the seventies, the rock bottom point of the drummer's downward spiral is no joke. Kicked out of Hole and having burned through all her finances, Schemel eventually wound up working the streets to support her habit. As a lesbian selling herself, she recounts how she could 'switch off' with men, and that vicious cycle drug-taking drowned out the feelings of disgust that came with using her body as currency to afford them. This sickening anecdote is tossed off in the same glib manner as the quip about lesbian get-up with no appropriate measure of gravity. Symptomatically, Hit So Hard doesn't properly consider the incendiary material it lays out, before retracting it in double time, turning milestone moments into footnotes. More than likely there's not a lot of wiggle room or want to probe the drummer's time on the streets with any great depth, but that decision to hold off smacks of a filmmaker's reticence to rock the boat than any lack of willingness on Schemel's part. This halfway house approach and inability to ask potentially alienating questions wastes much of the film's candid access and takes the sting out of the film's most scandalous insider scoop.

For the group's most mainstream effort, Celebrity Skin, Courtney Love enlisted the services of Michael Beinhorn, a man with a reputation for kicking drummers off albums and bringing in session players of his choosing. One of the assistant mixers recalls Beinhorn 'tormenting Patty for two weeks straight', making her record take after take and hitting the 'dim' button each time she started over, so that he could concentrate on his morning newspaper, rather than have to listen to her play. As Schemel progressively wore herself out, Beinhorn collected the worst of these takes and presented them to Love as good reason for letting her go. Such reprehensible conduct saw the producer receive a Grammy nomination in 1998.

Shrugging it off, Love is brashly accepting of such methods, insisting that all producers are assholes and that under Beinhorn, she understood that this was just part of the process of getting the record made ("He doesn't not do it"). Other female drummers interviewed (Debbi Peterson of The Bangles, Gina Schock of The Go Gos and Alice de Buhr of Fanny), none-too surprisingly find Patty's treatment disgusting and are deeply appalled by Love's treachery, not just as captain of the ship, but as a woman of enough power and influence at the time, who consciously chose not to rectify the situation by standing up to her producer. Such no-holds-barred slander really enlivens a film that is otherwise, disappointingly non-confrontational. For all the anger directed at her, it's Love's personality that perseveres; a devilishly loose-lipped raconteur, whose proclivity for mud-slinging casts the validity of every fantastic statement (Kurt hated his band mates who beat and bullied him apparently) into question. Always chasing the last word, Love is as outspoken and as outrageous as the notoriety that precedes her. Recounting a phone call her then homeless and estranged drummer made to her asking for drug money, it turns out that Love also has a great sense of humour about her ex-band mate being a crack head: "I hadn't done those kind of drugs at that time – I have now" she guffaws with fond hilarity. And while Ebersole has no trouble whatsoever getting Love to air her laundry, he flounders by letting other members of Hole off the hook so easily. In failing to get them to expand upon their initial statements concerning Schemel's hushed dismissal, the true depths of inter-band fractures – far beyond standardized 'creative differences' – can only be guessed at.

Melissa Auf der Maur stepped into the shoes of bassist Kristen Pfaff shortly after her overdose, not two months after Kurt Cobain pulled the trigger on the shotgun blast heard round the world. Into this musical family beset by tragedy came the Amazonian axe slinger, whose Viking performance stance (immortalized in silhouette on the cover of her astounding debut solo record) gave her the air of a mythical Norse Goddess. Offstage, the eccentric Canadian brought some much-needed sunshine during a period of rehabilitation. Simbiots not just as the ying and yang of the rhythm section, but as on-the-road soul mates, Auf der Maur quickly became Schemel's redhead sister and anchor through her various attempts to stay on the wagon. Reminiscing in the present, visibly you can see how important this bond was to both women, and the guilt Auf der Maur feels over not standing up for her best friend as she was bullied out of the studio is evidently still fresh years later. If the guilt of the moment extends to what happened to Schemel subsequently – stopping the two from speaking to one another as they once did – these are questions Ebersole is unwilling or too afraid to ask.

His proximity to his subject may explain Ebersole's failings as an interviewer, but as a documentarian there's a massive oversight impossible to excuse. The press notes and much of the chatter at the festival before the screening, misleadingly talked up the filmmaker's intention of establishing Schemel's importance as a female drummer and yes, during the film, many of the interviewees chime in on her style and technique. Why then, are Schemel's many other musical contributions outside of Hole (Juliette and the Licks and the Gina Gershon band among them) never discussed? Life as a drummer after Hole was an important step on the road to recovery for Schemel who nowadays is back behind the kit, teaching munchkin rockers in waiting. But If you happen to get up as the film fades out, you'll probably leave completely unaware of the fact that the Celebrity Skin fiasco was far from the last time Schemel made the linear notes of a commercially released record. A list of all the names she's played with since are insultingly relegated to a light speed end credits roll.

Undeniably, where the documentary really scores for diehard fans of either Hole or Nirvana, is the camcorder footage of Schemel crashing at the house of grunge royalty before and after Cobain hit the big-time. Love authoritatively stating that Schemel was Cobain's only friend, is the one time the truth of what's she's saying doesn't sound tinged with exaggeration. Babysitting their daughter Frances Bean while Cobain was working on new material and Love was presumably too bombed to do it herself, Schemel was right there, whenever Cobain emerged from the closet under the stairs where he wrote, goofing around and helping the tortured songwriter decompress in-between heavy sessions with a shared love of toilet humor, pop culture and 70s television. The footage is as tender as their friendship, the fuzzy intimacy of analog enough to make you feel as though you can reach out and touch a time that never will be again.

Despite many of the major reservations I have with the filmmaking, for the grunger, Hit So Hard is a vivid trip down memory lane, a triva-filled confetti cannon of the musical scene closest to my heart. I'm looking forward to seeing this again with like-minded friends on DVD and perhaps it can be re-named 'Live Through This' for that release, which as a document of survival and beating the odds is certainly more appropriate. Competent if incomplete, Ebersole lets himself down with a line of questioning not half as hard hitting as the decided-upon title promises. In terms of recent rockumentries it's not Pearl Jam Twenty, but it'll do until they finally give Layne Staley the cinematic elegy he deserves.

Screened at the 26th BFI London Lesbian & Gay Film Festival.

At present the film has no set UK release date but is being screened at the

Sheffield Doc/Fest 10th June.

|