|

"The Damned can now play three chords. The Adverts can play one. Here all four of them at…" began the print ad for the first rock concert that I ever attended. The Adverts were up first, then The Damned hit the stage. How appropriate, then, that the first punk rock record I ever heard was The Adverts' One Chord Wonders and the second was Neat Neat Neat by The Damned. I was at art school at the time and had been exposed to The Adverts' raw and energetic opening cannonade when a fellow student brought it in and played it during one of our easy-going drawing classes. I'd been reading about punk rock, but as a disagreeably contrary teen, I tended to kick against whatever my fellow students were embracing. But this changed everything. There was no "oh, that's rather good" about this – I was blown away by this single. Surprised at my reaction, the record's owner invited me to a party, something that didn't happen often to a person that others preferred to keep at a barge pole's length. The owner of the record seemed both pleased and surprised when I accepted the invitation, perhaps because he had succeeded where so many others had failed. It turned out to be a bit of a life-changing event. It was here that a mature student with whom I had struck up a friendship introduced me to the precarious pleasures of alcohol consumption, which effectively set me up for the excessive boozing of film school that was to follow. And I'd not been at the party long before someone demanded of its record-owning host, "Well, let's hear it!" This, it turned out, was the day that The Damned's second single – the aforementioned Neat Neat Neat – had hit the stores, and just about everyone there was aching to hear it. After playing it three times, its owner flipped the record over (feel free to look up what a record is in this context if you're too young to remember) and played the B-side, the even more furiously paced Stab Yor Back. He then introduced us to the band's playful edge by playing the bonus B-side track, Singalongascabies, which was exactly the same song but stripped of its vocals. I was completely hooked, then proceeded to drink myself into a vomiting mess.

A couple of days later, my new record-owning, party-throwing friend invited me and a girl he liked and a girl I rather liked to accompany him to see The Damned live at a concert in London, waving the aforementioned ad in our faces as a teaser. More new territory in the shape of my first rock concert and my first time getting home from London at some unspeakable hour of the morning. I can't remember the name of the venue (and oh, I did try to find it), but do recall that it was located underground and was poorly laid out for such an event, with a stage so lacking in height that it was hard to actually see the musicians unless you were in the crushed and bouncing throng at the very front. But The Adverts were good. The Damned were superb.

For those of us only just discovering the delights of punk rock who were not based in London, actually getting to hear what we were reading about was no easy feat in those early days. Back then, punk existed only in the form of live gigs, and most of those were confined to small venues in big cities or on the campuses in university towns. That, for us, was one of the key reasons that The Damned were so important. They were the first British punk band to release a single – the superb New Rose – and the first to release an album in the shape of Damned Damned Damned, a glorious collection whose famed cover image of the band members liberally spattered with pie debris apparently upset some conservative commentators, who doubtless honed in on the picture's probably unintended whiff of homoeroticism. The Damned were also the first British punk band to do a major UK tour and the first to tour America. As Mick Jones of The Clash points out in this very documentary, "we hadn't even got a record deal by the time The Damned had their first single out." Clearly, they were pioneers. So why is it when the evolution of punk rock is discussed, The Damned are too often side-lined or fail to get a mention? It's a question that Wes Orshoski's song-titled documentary, The Damned: Don't You Wish That We Were Dead attempts to answer and, to a degree, help to rectify.

There's little doubt that The Damned was one of the most distinctive of the first wave of big name UK punk bands. The original line-up – and the one that I saw live – consisted of lead vocalist Dave Vanian, guitarist Brian James, bassist Captain Sensible and drummer Rat Scabies, each of whom were visually distinctive in their own way. Dave Vanian kicked against the spiky haired punk ethic by dressing and making himself up like an Edwardian vampire, complete with slicked back hair, white face paint and black eye makeup and clothing. The energetic Captain Sensible would often come on stage wearing a dress or even a ballerina's tutu, plus the sort of silly plastic sunglasses you might buy on a drunken day trip to Margate. Rat Scabies had a habit of stripping to the waist to perform and was scrawny-looking enough to bear a slight resemblance to the first part of his adopted moniker. The least showy of the group was probably Brian James, but it was he that composed most of their early songs and as lead guitarist he was always as visible as his more flamboyant companions. Right from the start they were recognised as one of the most musically adept of the early punk bands, and as far as I am aware were the first to openly acknowledge the influence of Iggy Pop and The Stooges on the punk explosion by concluding Damned Damned Damned with a cover version of The Stooges' I Feel Alright.

Initially, Don't You Wish That We Were Dead plays out to the standard biographical formula, tracing the origins of the band and exploring its evolution with the expected combination of archive footage and interviews with band members and a good many of their musical contemporaries. There are some famous faces here, including The Pretenders' Chrissie Hynde (who was once part of the band in its earlier incarnation as Masters of the Backside), The Clash's Mick Jones, music producer Don Letts, TV Smith of The Adverts, Motorhead's Lemmy, Generation X's Billy Idol, Charlie Harper of The UK Subs, The Stranglers' Jean-Jacques Burnel, The Dead Kennedys' Jello Biafra, Blondie's Clem Burke and Chris Stein, Black Flag's Keith Morris, Depeche Mode frontman Dave Gahan, and a good many more. This is intercut with newly shot material in which live performances are mixed with off-the-cuff tour footage of the band as it is today.

What quickly becomes clear is that the uneven fortunes of the band were due in in no small part to its lack of long-term continuity, with a repeatedly shifting line-up kicked off by the critical and commercial failure of their second album, Music for Pleasure, which saw Scabies depart and the band dropped by indie distributor Stiff records, after which they broke up. What followed was a succession of rebirths with different drummers and bassists after Captain Sensible switched to lead guitar, and despite hopes to the contrary, a long-standing feud between Sensible and Scabies makes it unlikely that the band's original members will ever play together again. Their subsequent musical output has had its share of ups and downs, and once again it's impossible not to get personal here. Like many others, I wasn't a big fan of their 1977 Music for Pleasure, but championed their 1979 third album, Machine Gun Etiquette, from which were drawn three terrific singles, Love Song, I Just Can't Be Happy Today and Smash It Up. Their biggest success came in the shape of a cover version of Paul Ryan's Elouise in 1986 and an appearance on Top of the Pops that saw Vanian's vampiric image given a New Romantic makeover. I have a feeling this is where we went our separate ways.

It's a given that when approaching a documentary on a subject that is meaningful to us or with which we have a history, we'll all bring a degree of personal baggage to it, and on this score I'm definitely no exception. The Damned had a huge impact on my teenage years, hence my eagerness to cover the release of this most welcome documentary about them. And while the hook for me lies primarily in the band's formation and its early years, I was still interested enough in their post-Music for Pleasure evolution to stay hooked as the story made its rocky way to the present day. The thing is, when I reached the point where it seemed to me that this journey had effectively concluded and the credits were due to roll, the film hadn't even hit its halfway mark. Now, this issue with the film is likely mine and mine alone, as while I had hoped for a portrait of the band's formation and their early days as punk pioneers, followed by a second-half skip through their later work, what I got instead was a portrait at the band as they are today, one in which their early work is seen more as a prelude to the more interesting things that they later moved onto. Tough luck, ageing punk boy. There is, I guess, an inevitability to this structure, with director Orshoski given what appears to be free access to the band members on recent tours, resulting in what is likely several sizeable hard drives of spanking new footage, which ultimately wins out against a more limited collection of archive material of the band in their youth. But what there is of that is so good, and while I know my views are driven just a little by nostalgia, watching fuzzy, black-and-white footage of blonde-wigged Captain Sensible insulting the audience and the band wrecking their set at a riotous CBGB gig in New York is a lot more thrilling than the altogether slicker material of the reconstituted group performing New Rose on stage almost 40 years later, however good Vanian still sounds (and man, he still sounds great).

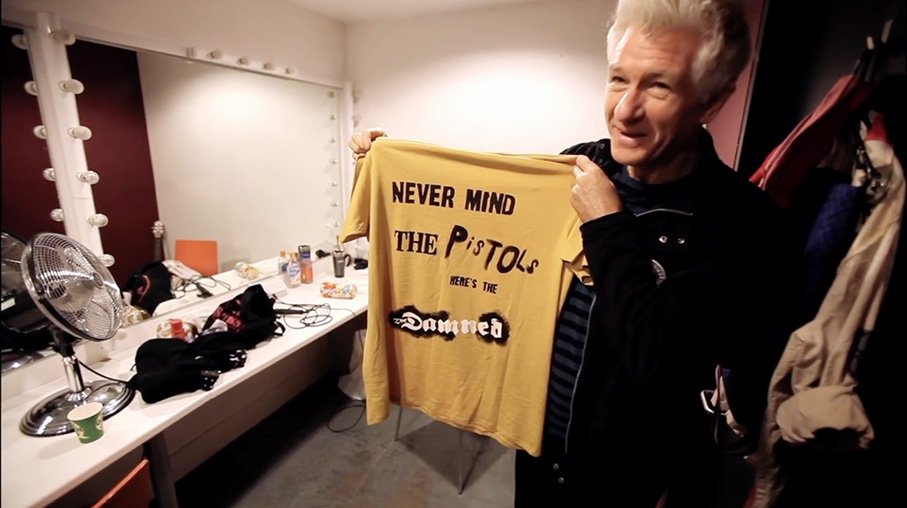

The second half still has its share of interesting material, and while the feud that developed between Sensible and Scabies is hardly one of history's great rock 'n' roll conflicts, it does provide a rare small peek beneath the surface of cheery prankster Captain Sensible's otherwise upbeat persona. This is at its most interesting in what looks like a surreptitiously shot backstage sequence in which the Captain is refusing to play Stab Your Back – the only song written by Scabies – as part of a live set on their recent 'Damned Damned Damned' tour, objecting to the violent implications of the lyrics and dismissing it as a sub-standard song that only ended up on the album by chance. A short while later, he is asked by Orshoski what he would like to hear Scabies say if he were to call him up now, and Sensible responds, "Sorry for being such a cunt?" Intriguingly, replacement drummer Pinch also says of the Captain at one point, "He has been the single most rude, unfeeling, embarrassing person that I've ever been around on many occasions," an aspect of his personality that the film chooses not to explore further, despite the effortless affable Sensible's own admission that he has a habit of being "an arsehole" at times. Mind you, having being reduced to tears at the memory of a time at which the band simply lost the will to play, Scabies has his moment of sweary aggression when he sounds off at Orshoski as he follows him along the street with his camera, angrily claiming that he doesn't fucking care about the documentary, about being in a group, or about anything much, and dismissing the band's contribution to music as insignificant in the grand scheme of things.

The relatively ordered structure of the first half gives way to something more disorganised in the second, as the film nips backwards and forwards in time and flits between disconnected scenes and changing band members at a sometimes disorientating pace. There's surprisingly little on the group's influence on the goth rock scene to come, and I had a nagging sense that the film runs for 110 minutes not because that was what it took to tell the story but because Orshoski just couldn't bear to cut any more of the footage he had spent so much time recording, which does result in some repetition and occasional point-labouring. But it's hard to get that disgruntled at a film that is so long overdue and gets so close to its subjects that you at times feel as if you're sharing backstage space with them or hanging out in their company as they recall their individual stories. There's some great material here and some still terrific music, and if the film helps a few of those younger souls who've come late to the UK punk scene to discover the work of one of its too often side-lined pioneers, then it will have done its job, and as someone for whom The Damned once meant so much, for that I applaud it.

The Damned: Don't You Wish That We Were Dead will be released by Kaleidoscope Home Entertainment on UK Blu-ray and DVD on 29 May 2017, and on digital download on 22 May 2017. This review is of the digital download version.

|