|

– PART ONE –

| |

"There is no gate, no lock, no bolt that you can set upon the freedom of my mind." |

| |

Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own, 1929 |

| |

"More women have more money and power and legal recognition than we have ever had before; but in terms of how we feel about ourselves physically, we may actually be worse off than our unliberated grandmothers . . . We are in the midst of a violent backlash against feminism that uses images of female beauty as a political weapon against women’s advancement." |

| |

Naomi Wolf, The Beauty Myth, 1991 |

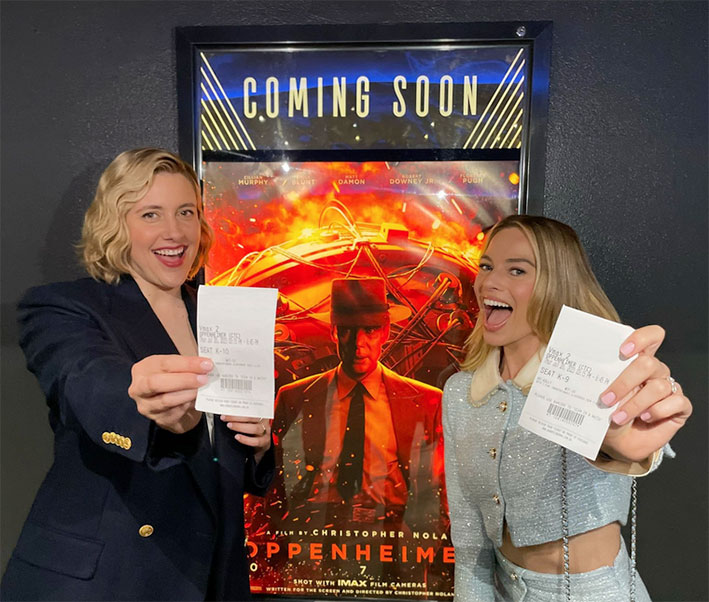

Landmark cultural events hurtle so rapidly into the past that time seems both compressed and stretched. There is now, incredible though it seems, a time before and after ‘Barbenheimer Day’, an event that already seems a distant memory. Whether you favoured Greta Gerwig’s Barbie or Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, opted for the opening night double-bill or turned a blind eye to the spectacle entirely, you can’t have avoided the hullabaloo surrounding it. For good or ill, more has been said and written about these films recently than about child poverty and climate collapse – partly because Gerwig and Nolan raise hugely important questions about who we are and where we come from. Given that these twinned but numberless films are neither sequels nor prequels, that they are live-action not animation features, and that they’ve generated full houses and colossal box office takings, it’s hard to argue with Francis Ford Coppola’s claim that their release represents a ‘victory for cinema’.

Such was the febrile reaction to the ingeniously hyped same-day release that it initially proved difficult to secure a ticket for either film. That’s what a $150 million marketing budget buys. Josh Goldstine, Warner Bros.’ ‘President of Global Marketing’, says: ‘I won’t comment on the budget [Ed: We thought you might not]. The reason people think we spent so much is that it’s so ubiquitous. That’s a combination of paid media and how many partners came to play with us’. When I eventually bagged a seat, I was moved almost to tears by the buzz, and thrilled to be in an excitable audience, for a sold-out screening, for the first time in years. Cinema was back with a vengeance. Once again, folk were flocking to theatres in their droves to share experiences joyful and sad in a darkened room. In the case of Nolan’s three-hour-long epic, even the warmth and depth of film was back, as celluloid again unspooled in projection rooms across the overdeveloped world. Things we thought vanished for ever were suddenly back and that felt like a fine thing. ‘A victory for cinema’. Wow. Who saw that coming? Mattel and Warner Bros. possibly.

The timing was astonishingly perfect. As the Hollywood writers’ strike enters its fourth month and actors join authors on the picket lines, along trot two spectacularly successful films, highly distinctive films to remind studio managers what they stand to gain by granting the imagination free reign and by adequately rewarding those who produce their profits. Possibly also to remind Greta Gerwig that signing up to work for the man does damage to low-and-middle budget filmmaking, to those intent on making the kind of films she used to make, before she sold her soul to mammon. How Gerwig and the big studios needed those reminders and how cinema needed that shot in the arm. The COVID pandemic combined with the advent of streaming services to precipitate a collapse in cinema admissions comparable to the low-point of the mid-1980s. It also lead to an increased fragmentation of audiences and a further erosion of already fractured social cohesion. In this context, the Barbenheimer event appears not only as a glorious rebirth of cinema but also as a revival of the increasingly unfashionable act of ‘going out’ rather than ‘staying in’, of being as one with one’s fellow citizens – a victory too, then, we might say, for that embattled sense of communal togetherness that underpins human solidarity. As has been said, there’s a lot going on here.

The release and reception of Barbie, in particular, already feels like one of those seismic cultural events that embed themselves in collective memory. Such rare events can change behaviour patterns and shift the terms of public discourse. It feels as though everyone’s talking about Barbie and will for years to come. In our age of inane Twitter soundbites and narcissistic Facebook posts, it is unsurprising that the debate hasn’t always been temperate. Gerwig has clearly touched a raw nerve. Hot opinions have been and are being expressed. People have taken and are taking sides. It has been fascinating, if often horrifying to track the wide palette of thought and feeling generated by the film’s many mixed messages. The commentariat may have divided us into ‘Team Barbie’ or ‘Team Oppenheimer’, but the polarisation brought about by Barbie is of a different magnitude. It is big. It’s bigger than cinema. This might be or become a generation-defining schism. Then again, it might not. Crazes fizzle out. Long after the current fashion for pink and all things Barbie has evaporated, though, the debate on the issues raised by Barbie will continue. All of which is as good a reason to review the film as any. As Christopher Hitchens once said, ‘If you care about the points of agreement and civility . . . you had better be well equipped with the points of argument and combativity, because if you are not then the ‘centre’ will be occupied and defined without your having helped to decide it, or determine what and where it is’.

Before any ‘points of agreement and civility’ can be reached, a detoxification and of debate must take place. Without it all sides will simply dig into their respective foxholes or trenches and open fire across ‘no man’s land’. The minute Fox News or the BBC denounce Barbie as woke or ‘anti-male’, the massed ranks of the conservative echo chamber are mobilised and on the march. The minute The Guardian or The Nation declare a right-backlash to Barbie, the massed ranks of the liberal echo chamber are mobilised too. It feels as though everybody’s talking but nobody’s listening. Maybe the time for talking is over? Maybe we should let the battle of ideas take its course? The Liberal politician Isaac Foot captured something of the continuing divisions caused by the English Civil Wars when he said, ‘I judge a person by one thing: which side would he have liked his ancestors to have fought on at Marston Moor’. Might generations to come ask, ‘Which side were you on in the battle of Barbie?’ It might appear idiotic even to suggest as much, but you take my point. In discussing Barbie we are, in a way, refighting the battles of Second Wave Feminism. The way people position themselves in relation to the film bears comparison with the way a generation divided on, say, the Vietnam War. There’s a lot at stake so tempers will flare.

In a world gone mad on money, news items on box office takings and records broken inevitably dominated early coverage of the film. Since then, untold human hours have been expended in online tittle-tattle about it and on a demented collective research project intent on presenting the insatiable public with every imaginable detail relating to Barbie, the doll, and Barbie, the film. No stone was left unturned. Entire offices were set to work answering every anodyne question imaginable on the subject of the moment. What colour socks does Greta Gerwig prefer? What colour was the first Barbie’s après-ski sweater? Some questions, though, didn’t make the cut. What’s your poison? Capitalism. What’s cooking at the Barbie-queue? Isn’t Barbie one big shiny, cynical advertising campaign packed full of product placement? Can’t Mattel’s sale of Barbie dolls at the rate of over 100 per minute, and rising, be viewed an environmental catastrophe, even setting aside Barbie’s carbon footprint?

Such questions hint at something darker at play behind the clamour and glamour, and beyond the ken of Barbie. The film will certainly fuel a consumer feeding frenzy. It will certainly shift polluting truckloads of non-biodegradable trash that will then pollute our rivers and seas, but, hey, it might also save cinemas, if not animal species from extinction. Ah, but then again, I hear the argument go, there will be 'literally' no cinemas if we are buried beneath rising sea levels; ah, it's all so confusing.. Even if this single singular film cannot rescue cinema alone, it has certainly given it a huge lift. Even if it faces two ways at once, it has also stirred up a hornets’ nest and provoked heated, occasionally even productive public debate. Being a tricksy, loosely feminist film that, much like the legendary doll at its heart, simultaneously endorses and challenges patriarchy and consumer capitalism, it may also, depending on how the debate on it shakes down, lead to positive change and enhance our collective wellbeing. Equally, it may not, that it appears even to be a possibility is something. Not bad for a film focused on a range of synthetic dolls manufactured from polypropylene, PVC and vinyl compound.

Barbie is high camp burlesque with a sting its tail. It is bold and brassy, smart and sassy, riotously enjoyable and intriguingly thought-provoking. J.B. Priestley felt that humour might be described as, ‘Thinking in fun while feeling in earnest’ and that also describes the film well. A complex, cleverly crafted mash-up of daffy jokes and on-point critique, it is, by turns, preposterous and piquant, silly and serious-minded. It is consistently surprising and even – Up to a point, Lord Copper – subversive. Riddled with contradictions itself, it turns a spotlight on the contradictions of consumer capitalism. Few mainstream films of recent years have so valiantly flicked the ears of the money men. Few have nibbled away so impotently at the corporate hand that fed them. For no number of principled feminist monologues can undo the untold damage done to feminism by the Barbie myth and the beauty myth.

Early in the film, Barbie brings a girls’ night party crashing to a halt by asking out loud, ‘Do you guys ever think about dying?’ It is the key note scene of the film, the pivot on which all else turns. I propose we follow Barbie’s lead, put the Barbie pyjama party on pause, flip Barbiemania on its head, and consider the film in the round, fluffy flaws if not warts and all – for although Gerwig deserves praise for the diversity of the picture she paints, no blemish was allowed to defile it, no spot stains the unnaturally white teeth of her astonishingly talented cast, perish the thought. An anti-septic plastic dreamland where food falls from the trees, or would do if there were any trees, a fantasy pseudo-suburban playground a bit like the U.S.A.. I’ll not be moving there any time soon.

The film begins with a deft reworking of the ‘dawn of man’ sequence from 2001: A Space Odyssey that immediately highlights the conundrum, doublespeak and ideological crisis at its centre. Helen Mirren’s voiceover says, ‘Since the beginning of time, since the first little girl ever existed, there have been dolls.’ Girls ‘could only ever play at being mothers, which can be fun – for a while. Ask your mother!’ As a monumental Barbie towers above them, the girls discard their tea sets and smash their old-fashioned dolls. The mise en scene implicitly suggests that domestic drudgery has been abolished, Betty Friedan’s ‘happy heroine housewife’ is a thing of the past, and the future wears lipstick, sunglasses and swimwear. As the doll winks at us, the Dame tells us, ‘the problems of feminism and equal rights have been solved’. If only that were so. If only the restrictive depredations of the domestic hadn’t been replaced by the Iron Maiden of the beauty myth. If only the world were in better shape.

That opening scene alone attests to the impossibility of separating Barbie from the matters of import attached to it. You have to feel for Greta Gerwig, at the centre of a perfect storm as she is. She is getting both barrels from both sides. Well, from all sides really: to some she is a vindictive arch misandrist, to some she’s a champion of the feminist cause, to others a traitor to it, to others again a sell-out snake oil merchant. But there is more, much more at stake here than just the delicate matter of Gerwig’s personal integrity. We shouldn’t be stampeded into uncritical support for her because of the right-wing backlash against the film or because the alt-right, incels, and non-aligned reactionaries everywhere are playing the part of ‘humourless lefties’, squealing about TikTok feminism, calling for Barbie boycotts, and burning their Barbies. The likes of Piers Morgan and Ben Shapiro are paper tigers easily swatted in a fair fight and, and, anyway, best ignored. We can be well-disposed to Gerwig and appreciate her talent and guts without letting her off the hook. She has plenty of questions to answer.

As Jessica Defino says in her scintillating and forensic dissection of Barbie on The Unpublishable: ‘It’s clear that writer-director Greta Gerwig aims to subvert much of what the Mattel toy symbolizes in American (and, I’d add, global capitalist) culture: conformity, compliance, the objectification of women and girls . . . [but] you cannot subvert the politics of Barbie while preserving the beauty standards of Barbie. The beauty standards are the politics . . . You cannot subversively, satirically, or ironically produce and consume things. The idea that you can is solipsistic and conservative. Production and consumption have collective consequences, whether you adopt Barbie-inspired beauty behaviours with a knowing wink or not!’ We’ll come to those collective consequences in due course. I’ll focus on the film in Part One and those consequences in Part Two, but, first, a brief spoiler synopsis might be useful. You, dear reader, may not need one, but so much gibberish has been talked about Barbie and its purported politics that it seems sensible to establish, from the start, that we’re talking about the same film.

Happy-go-lucky ‘Stereotypical Barbie’ (Margot Robbie) is disturbed by irrepressible thoughts of death and malfunctions. She develops creeping cellulite, her milk curdles, her shower runs cold, her unnaturally arched feet fall flat. She visits wise ‘Weird Barbie’ (Kate McKinnon) for advice, leaves the matriarchal Lalaland of Barbieland for the ‘Real World’ in search of repair and redemption. Once there, she meets Gloria (America Ferrera), the Mattel staffer responsible for her morbid turn, and Gloria’s feisty ‘twixt and ‘tween daughter, Stella (Ariana Greenblatt), who calls her a fascist. Barbie learns to cry, gains a heart, and, finally, becomes painfully, proudly human. Barbie’s doting other, let’s call him ‘Stereotypical Ken’ (Ryan Gosling) joins her on her voyage of discovery, falls under the spell of horses and The Patriarchy, returns home to lead the other Kens in a reactionary challenge to the Barbie-run social order, brainwashes the Barbies, is faced down by them after they deprogramme themselves, repents his sins, and, finally, becomes kinda human too.

Barbie gently ribs many of the more asinine and pitiable behaviours of the modern boy-man (the Kens) while foregrounding the talents of competent professional women (the Barbies). The boy toys parade and patrol Barbieland’s beaches while the bright girls make things tick. This is the just and natural order of things in the manosphere of Barbieland – where the Kens are comic-book dimwits and the Barbies count among their number a diplomat (Nicola Coughlan), a doctor (Hari Nef), a lawyer (Sharon Rooney), a physicist (Anna Mackey), a Nobel laureate (Alexandra Shipp), even a mermaid (Dua Lupa) and the President (Issa Rae). This may reflect bourgeois feminism’s traditional disdain for working class women and the lumpen secretariat, but even at this low-level Barbie operates as a valuable cultural corrective. That most of the ‘characters’ in it are based on or replicate historic Mattel dolls adds a dollop of droll, self-reflexive irony to the film and highlights the double-bind it is trapped in.

Although Barbie skewers the flimsy superficiality of go-girl and yo-bro solidarities alike, it is at its brilliant best when lampooning infantile masculine behaviours: the cockiness and competitiveness, the patronising mansplaining and car fetishism, our failure to use those flappy things on the sides of our heads effectively, the unwarranted arrogance and vanity of our sex. I was tickled particularly pink by the beach campfire scene in which the narcissistic Kens strum guitars and sing at the Barbies – who disingenuously flutter their eyelids though presumably bored senseless. Ryan Gosling’s schlocky and mawkish rendition of Matchbox Twenty’s notorious mock-macho MOR anthem ‘Push’ deserves special praise. It is a comic masterclass. For one so bright, Gosling plays dumb astonishingly well, but then he’s proved himself versatile enough to veer from violent machismo (Drive and Only God Forgives) to playfully whacky (The Nice Guys) and suavely sophisticated (La La Land) with ease.

Margot Robbie steals the show though, not least because she looks so uncannily like Barbie (witness her turn as Sharon Tate in Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood). Like Gosling, Robbie plays dumb all too well; in her case with a panache that recalls the inimitable Judy Holiday in George Cukor’s imperishable Born Yesterday. In one of the film’s many hilarious moments Barbie, speaking from deep within her existential crisis, says ‘I’m not Stereotypical Barbie pretty’. At which point Helen Mirren’s narration interjects, ‘Margot Robbie is the wrong person to cast if you want to make this point.’ Indeed, and this was not a case of perfect casting decision: Amy Shumer, Anne Hathaway, and Gal Gadot were lined up to play Barbie before Robbie secured property rights to Barbie (through her partner’s company LuckyChap Entertainment) and stepped effortlessly into the famous doll’s high heels.

When Robbie asked Greta Gerwig to write direct Barbie, having been bowled over by her work on Ladybird and Little Women, Gerwig agreed only on the condition that her partner Noam Baumbach be brought on board. That deal immediately clinched the film’s success, because the golden couple’s razor-sharp writing, storytelling acumen, and cineliterate command of diverse materials lift a film that could so easily have flopped in less dexterous hands. Every cloud has a silver (often pink) lining, and while the pandemic decimated cinemas it also afforded Baumbach and Gerwig the time and space to craft a superb script for Mattel that surpasses even their brilliant work on Frances Ha and Mistress America for anarchic energy, acerbic wit and sheer kick-ass chutzpah.

The Matchbox Twenty song Ken and the Kens band together to sing at the Barbies is darkly misogynistic (‘I wanna push you around, well I will, well I will/I wanna push you down, well I will, well I will’), but Baumbach and Gerwig deflate and leaven its impact with impeccable timed deadpan humour. They deploy a similar strategy to make mock of the lunacy of patriarchy throughout the film. Poor confused, deluded Ken, for example, laughably comes to equate horse-power with male dominance after he sees mounted police in the ‘Real World’ and reads about cowboys and horses there. Back in Barbieland, he subjugates the Barbies and seizes power, but eventually recants, saying, ‘To be honest, when I found out patriarchy wasn’t about horses, I lost interest’.

Although Barbie contains more delightful one-liners than several Netflix comedy series combined, its humour occasionally falls as flat as Barbie’s feet. This is partly because certain territorial cultural references stall in mid-Atlantic and fail to land on either side of the pond. The film was shot at the Warner Brothers studios outside Watford and Venice Beach outside Los Angeles, so it is, in that one sense at least, an Anglo-American affair. Ludicrously, little old England appears larger than Australia and Europe on Weird Barbie’s controversial map – which replaces Scotland with a crown, ignores Wales entirely, and left me wondering if Baumbach and Gerwig (or Mattel) hadn’t strained too hard for an elusive transatlantic entente or, to be blunt, towards the lucrative ‘English’ market. Be that as it may, their recurring, presumably specifically American in-joke about Ken’s ‘Mojo Dojo Casa House’ completely passed me by and their impish nods to Monty Python and the BBC’s Pride & Prejudice might not travel well in the other direction either.

Perhaps I underestimate the reach of our own pop culture in so saying. It’s a moot point, anyway, if we agree that culture is a common treasury built for everyone to share. It’s irrelevant, too, in our era of global capitalist consolidation – in which nation states that lost their historical mission long ago continue to corrode from the inside out. If the film’s humour doesn’t always hit the mark, it may equally be because the laughter comes so fast and frequently or because Baumbach and Gerwig clearly indulged themselves at times by ‘literally’ recycling their own private jokes. Also, perhaps – dare I say it, I do – because they may simply too subtle, too bright for mass audiences. Case in point, the charged scene in which Barbie meets Sasha. The tween tells the doll, ‘You set the feminist movement back 50 years, you fascist!’ Bewildered and wounded, Barbie flees, before murmuring to herself, sotto voce and through tears. ‘She thinks I’m a fascist! I don’t control the railways or the flow of commerce’. It may appear patronising to say such a seemingly outrageous thing, but I base my conjecture on the hard evidence of the reactions I witnessed. Watching the film, it felt at times as though the audience were caught between baffled incomprehension and let-rip laughter – as if there was a collective from as certain scenes unfolded.

Does the soundtrack succeed? Think of Grease and Saturday Night Fever and catchy showstoppers immediately spring to mind, unbidden; not so, for me, with Barbie. I relished the strains of ‘When Times Go By’ that accompany the immediate appearance of the Warner Bros. logo, but I felt the music went downhill from there. A passing nod to Toni Basil’s ‘Hey Mickey’ (‘Oh Barby, you’re so fine, you’re so fine you blow my mind’) pricked my ears up, if briefly, but then I’m not Mattel’s ‘target demographic’ so my opinion on the subject is irrelevant. Mercifully, Aqua’s chart-topping techno-ditty ‘Barbie Girl’ is still the subject of legal battles, so we were, at least, spared its suspect jaw-dropping misogynistic bile (‘I’m a blonde bimbo girl in a fantasy world/Dress me up, make it tight, I’m your dolly . . . Make me walk, make me talk, do whatever you please/I can act like a star, I can beg on my knees’). Do the dance sequences work any better? Despite appearances to the contrary (Guys and Dolls this ain’t), yes, I think they do, the choreography is flawless and the dancing tip-top.

All told, there are pleasures aplenty for one and all in Barbie. It’s unlikely, though, that it would have had such vast crossover appeal if it were just a glorious giggle, mere knockabout fare, and Good Clean Fun only. The film’s success rests partly on Gerwin’s rare gift for weighing the silly and serious and then achieving equilibrium. Beneath the pavement, the beach; beneath the glittering disco ball, the mess of mortality. Hey, ‘Do you guys ever think about dying?’ If the film is patchy and its soundtrack disappointing, if its jokes often fall flat, it sure sizzles sometimes, and we can all, let’s hope, warm to the tenderness and truth at its heart – because, after all, we are all ‘of woman born,’ we all age and cry, laugh and die. We sigh together when Barbie says to a lovely old woman seated beside her on a bench, ‘You’re beautiful,’ and she replies, ‘I know!’ And the scene becomes more poignant still when we learn that the woman in question is a close friend of Greta Gerwig: the Oscar-winning costume designer Ann Roth, whose credits include Baumbach’s Margot at the Wedding, While We're Young and White Noise.

Barbie’s journey to enlightenment and self-awareness contains clear echoes of the odyssey of Hickory, Hunk and Zeke – the Tin Man, the Scarecrow, the Cowardly Lion – in The Wizard of Oz. Barbie also travels in search of a brain, a heart and courage in her quest. Like Dororthy’s travelling companions, the stereotypical and metaphorical dolls strive to become what they want to be or feel they should be. Like the sham Wizard, Greta Gerwig asks us to lean in and says, ‘Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain’. If George Cukor and Gene Kelly are Gerwig’s guiding lights, The Wizard of Oz is the film’s touchstone. Her colour-saturated aesthetic was clearly shaped by soundstage musicals. She has said she was aiming at a look of ‘authentic artificiality’ and also acknowledges the influence of films as various as A Matter of Life and Death, Grease, Madame de..., The Matrix, Modern Times, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, Rear Window, The Red Shoes, Saturday Night Fever, Playtime, Singing in the Rain and The Truman Show.

As surely as the cast’s flawless performances and the film’s foxy quickfire script, it is Baumbach and Gerwig’s sure-footed deployment of such cinephile influences that make Barbie shine so. Above all the film owes a debt (as did Frances Ha and Mistress America) to the expertly executed one-liners and hilarious pratfalls of screwball comedy, to those very adult films Hollywood once excelled in, films that blended the silly and serious – most obviously, to Adam’s Rib, His Girl Friday, People Will Talk, The Philadelphia Story and, without doubt, Gold Diggers of 1933. All aboard with the Gold Diggers of 2023!

A less obvious influence on Barbie is the refreshingly combative work of Lina Wertmüller. In 2019, Greta Gerwig joined Jane Campion on stage to present the late, legendary Italian maverick with a well-earned Honorary Oscar for a lifetime’s achievement. Wertmüller became only the second female director, after Agnes Varda, to be so honoured. She would have deserved such recognition even if she’d only ever made Seven Beauties instead of the 30 films she created in a career of restless invention. Hell, she’d have deserved the award even if she’d only made the unforgettable first four-and-a-half minutes of that extraordinary film. Oh yeah.

Speaking at that ceremony, Jane Campion recalled seeing Lina Wertmüller address an audience at the Australian Film and Television School, where she herself was then a student. When asked for advice on the business of how to raise money for films, Wertmüller, the socialist firebrand, replied, ‘You beg. You borrow. You steal. You do whatever is necessary’. Greta Gerwig is no socialist and she long ago abandoned that guerrilla approach to filmmaking, but, like Jane Campion, she inherited from Wertmüller a non-didactic approach to politics and a certain indomitable fearlessness; in Gerwig’s case, a fearlessness fully up to the daunting challenge of making Barbie, the audacity, too, to critique the values associated with the very doll her film was designed to sell and will sell so well.

Gerwig can only have drawn strength from Wertmüller’s pioneering example, much as Barbie does from Ruth Handler, the creator of the famous doll (beautifully played by Rhea Perlman). ‘We mothers stand still,’ Handler tells Barbie, ‘so our daughters can look back to see how far they’ve come’. There follows a tender found footage homage to mothers, real and symbolic, which Gerwig assembled from home movies donated by the cast and the friends. We might think of Wertmüller as Gerwig’s cinematic mother. Wildly different though their respective films are stylistically, they demonstrate a shared commitment to collaborative working practices and the establishment of co-operative, democratic on-set environment – thereby shaming the kind of authoritarian (mainly male) directors who bark orders from on high. Before shooting began on Barbie, Gerwig gathered her cast together for an ice-breaking party in Mayfair, at Claridge’s. The camaraderie created on that one night alone pays dividends in the pyjama party scenes at Barbie’s dreamhouse. That the Kens opted out of staying overnight might have been no bad thing.

PART 2 >>

|