| |

"Ireland was up in arms: you can slowly crush the Irish, you can take the ground from under their feet and they won't notice they're sinking down; but if you hit them, they'll hit back." |

| |

Bernie Devlin, The Price of My Soul |

| |

"All wars are fought twice: the first time on the battlefield, the second time in living memory." |

| |

Viet Thanh Nguyen, Nothing Ever Dies |

Irish film-making couple Christine Malloy and Joe Lawlor, aka Desperate Optimists, have travelled far since they met and fell in love as students at progressive Dartington College, Devon in the early 1990s. From their early avant-garde work in theatre, through a series of essay films and gallery video projects, to their 2008 debut feature Helen and latest film Baltimore, they appear to have moved closer to the mainstream by the year. A lazy hack might call Baltimore 'their most accessible film yet.'

Appearances can be deceptive though. Desperate Optimists have eschewed the dead end of elliptical asepsis and insular aestheticism and pursued their search for wider audiences while resolutely resisting the honey trap of commerce. Ever questing, always questioning, they have charted a steady course though those respective perils by balancing the competing merits of 'a poetics of documentary' or 'the creative treatment of actuality' and the crowd-pleasing attractions of narrative cinema. In so doing, they have carved out a unique space in our film culture.

Deperate Optimists Christine Malloy and Joe Lawlor

The essay film is, in Laura Rascaroli's phrase, cinema in the first person. It is a hybrid form characterised by archival appropriation, by the subjective, contingent, playful and private. In their essay film The Future Tense, the Dublin-born, London-based Desperate Optimists interrogated the ways their own individual identities relate to notions of English and Irish nationalisms. With impish wit and forensic acuity, they unpack their own feelings about Irishness and the ludicrous nature of borders (be that lines randomly drawn down roads or across seas).

They do so while scouting locations for a potential new home and a then nascent film on Rose Dugdale – the English heiress who gradually liberated herself from the biting shackles of patriarchy and privilege, reinvented herself as a revolutionary committed principally to the armed struggle in Ireland, and died peacefully in her sleep last month – just a week before Baltimore was released and the day before she was due to see Imogen Poots play her on screen.

In The Future Tense, Desperate Optimists consider a return to their native land, and wonder what their daughter, Molly Rose Lawlor, would feel and think if they did. Moving restlessly to and fro between the kind of experimental essay film associated with Véréne Paravel & Lucien Castaing-Taylor and the kind of taut psychological thriller typified by Cathy Brady's Wildfire, Malloy and Lawlor have consistently circled the point where the personal meets the political. RTÉ called their 2019 breakout feature Rose Plays Julie 'A study of identity, its construction, demolition and reconstruction'. Apt, that, because Desperate Optimists tend to focus on what they call 'identity under duress'.

In Baltimore (released as Rose's War in the USA), Poots plays Rose with poise and passion. This is her finest hour and it feels like she was made for this starring role. She began her film career in James McTeigue's V for Vendetta, in which a masked freedom fighter takes on a cruel authoritarian state, and more recently starred in Lorcan Finnegan's Vivarium, as a woman trapped in a tidy dystopian hell. Perhaps that background helped her tap into her inner revolutionary? Perhaps it helped her better understand her subject? Be that as it may, whatever anger she draws on in Baltimore feels real.

Imogen Poots as Rose Dugdale in Baltimore

If Poot's French accent, by contrast, feels faux that's because Dugdale's was when, in 1974, she and a PIRA service unit pulled off the biggest art heist in history and made off with 19 priceless paintings – including works by Gainsborough, Goya, Rubens, Velázquez and Vermeer. They did so in an attempt to secure the return of IRA volunteers Dolours and Marian Price to Ireland from Brixton prison, where they'd been incarcerated for the 1973 Old Bailey bombing.

Poots is adroitly abetted by a uniformly superb ensemble cast featuring a walk-on part for Molly Rose Lawlor. Tom Vaughan-Lawlor is pitch perfect as astute, alert and softly-spoken IRA volunteer Dominic; Andrea Irvine plays steely Lady Clementine Beit, victim of the heist, with impeccable precision; but Dermot Crowley steals the show with his heartrending portrayal of an old man, Donal, who had a farm near the country house Dugdale and her comrades robbed. Gradually losing his eyesight, embroiled in events beyond his ken, Donal senses something is afoot, turns tout, and informs on the group.

The real-life farmer threw himself off a cliff soon after Dugdale was arrested, so we're left replaying Anatomy of a Fall in our heads. Did he leap to his death because stricken by a guilty conscience or was he driven to that desperate act by fear of reprisals. Did he fall or was he pushed? The malodorous fog that swirled around the Troubles and Frank Kitson's dirty war in Ireland obliterated all light, so we may never know.

More concretely, Baltimore asks 'Who was Dr. Brigit Rose Dugdale?' and 'What made her tick?' The film attempts to answer those questions with the help of dream sequences, flashbacks, and several metaphorical foxes. Early in the film, Rose is 'blooded' after a fox hunt on her family estate in Devon. Later, she is surprised by her parents while robbing their house for PIRA fighting funds and slams a fox's tail down hard on their dining table. The implication seems to be that she learnt cruelty and violence from her class and returned it with interest. While lying low after the heist, Rose sees or senses suspicious movement, cocks her revolver to investigate, only to find not a British sniper but a beautiful vixen quivering beneath a tree. The hunted turned huntress? As the film approaches its climax, she inadvertently runs over a fox, shoots it in a mercy killing, and later buries it. Does this represent the death of innocence for both the fox and Rose herself?

The symbolism may be overwrought but, like the dream sequences deployed to imagine Dugdale's thought processes, it is defly done. We can see clearly enough what drew them to her compelling story (aren't revolutionaries, after all, desperate optimists too), just as we can see what might've drawn Rose Dugdale to Constance Markievicz but, here's the rub: the focus on the personal that seeps from the essay form into their fiction comes at the expense of the political. That process of seepage and elision needn't matter. Indeed, it actively enhanced their earlier work and does so again in Baltimore with their passing allusion to the sacrosanct importance of art and beauty. More generally, though, because Rose Dugdale was nothing if not a political animal, damage is done to the whole. We're left feeling slightly robbed, as though we're not in possession of the full picture.

John Corner spoke of a 'post-documentary' audiovisual culture. Neil Postman spoke of the seepage of entertainment values into political discourse in Amusing Ourselves to Death. By brilliantly second-guessing what might have made Dugdale what she was and electing to pursue their enquiries in fictional form, Desperate Optimists elide the importance of class struggle and the incandescent energy of her times in her formation. They narrow Dugdale's life down to the heist and turn up the volume on the soundtrack for dramatic effect. In so doing, they largely ignore the facts. They can be forgiven for doing so given that the audience for documentaries and engaged cinema is shamefully small in comparison to that for glossy fabulations – be they as artful as Baltimore is or as crass as most Monoform entertainments are.

It is not their fault, of course, that interest in politics is at an all-time low and that the deck is stacked against documentary. How could it be otherwise when what passes for politics today has been so thoroughly besmirched and debased, not least by self-serving machine politicians - and to such an extent that Georg Konrad defined the medium of politics as 'power over people – power back up by weapons' and that Jean-Luc Godard felt politics was now 'the voice of horror'? Such is the stench emanating from the corridors of power, such is the often baffling, always cacophonous din surrounding myopic identity politics that millions have turned aside from civic and political engagement, shaking their heads, blocking their ears, and holding their noses. And when what passes for parliamentary democracy is conducted without popular participation and self-management, when the state need no longer fear the passions of the crowd, the political class alone occupies the stage. In such a dispiriting context, facts find it hard to gain a foothold and hearing, so let's balance things out by considering a few facts of Dugdale's life.

One of the many riveting mysteries probed in Baltimore is how 'traitors' are formed and what leads them to switch sides. That question has fascinated folk down the centuries and has most recently been embodied by the likes of John Emery, Stoker Rose and William Joyce on one hand; Klaus Fuchs, Harry Gold, John Herbert King, George Montague Nathan, Julius Rosenberg, Constance Markievicz and Roger Casement, among others, on the other. In Heiress, Rebel, Vigilante, Bomber: The Extraordinary Life of Rose Dugdale, Sean O'Driscoll says that his subject's transformation and politicisation happened 'incrementally.'

Born into the Devon aristocracy in 1941, she curtsied to the Queen at a 1958 Buckingham Palace debs' ball, in 1959 she challenged the fetid misogyny of the all-male Oxford Union debating society while gaining a Philosophy degree. By the early 1970s she had sloughed off the dead weight of her inheritance, embraced socialism and divested herself of wealth by contributing considerable sums to, for example, the Tottenham Claimants Office which she co-founded.

By 1972, disgusted by Bloody Sunday, she had joined the Provisional IRA. She ran guns for the Provos ('God made the Catholics, but the Armalite made them equal'), attended training camps in Cuba, trained Farc rebels in Columbia, gave birth to a son, Ruairí, in Limerick gaol while serving six years for the heist, became a Republican explosives expert upon her release while working to sweep drugs from the streets of Dublin, and was buried in Glasnevin Cemetery with full honours. An extraordinary life indeed. Identity under duress in extremis.

Like many in her generation, Rose Dugdale was swept up in the rising tide of young energy and joy, the escalating mood of hope and radical revolt that marked the sixties or, at least, the New Left then. She reached her majority during a time for taking sides, when battle lines were clearly drawn. We know that she saw Dr. King speak around the time she earned a Masters at Mount Hollyoak, Massachusetts with a thesis on Wittgenstein, and just before she secured her Doctorate in Economics at the University of London, where she also taught.

So much for the facts, let’s speculate, as the film does. She may have heard King's famous New York speech against the Vietnam War (delivered a year to the day before his assassination), in which he said: 'True compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar; it is not haphazard and superficial. It comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring. A true revolution of values will soon look uneasily on the glaring contrast of poverty and wealth.' If Dugdale wasn't present in person when King said those words, she would have been aware of them. They would have resonated with her, as would Dr. King's call for that irreversible 'shift from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society' which alone could defeat 'the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism and militarism.' She would have thrilled at his thunderous declaration that, 'There comes a time when silence is betrayal.'

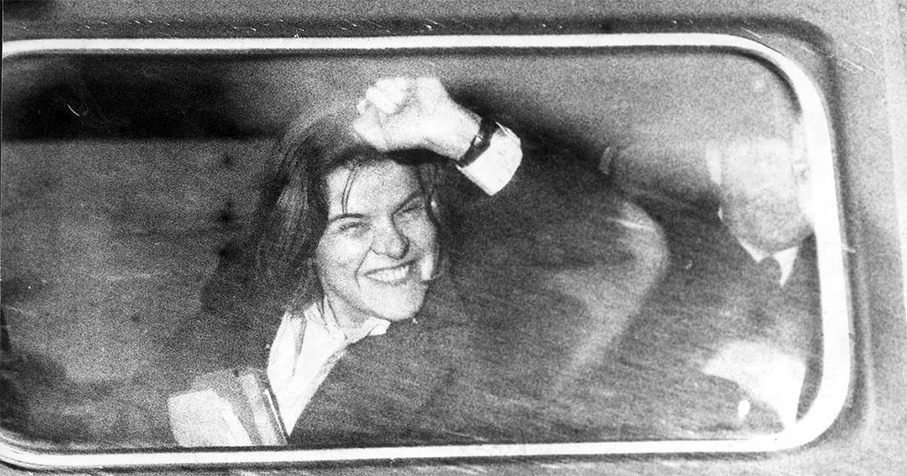

Dr. Dugdale may have rejected Dr. King's call for non-violence in part because she felt his assassination intensely and deeply. Of course, lynchings, police brutality and assassinations (Fred Hampton, Dr. King, Malcolm X, et cetera) loom large in the the African-American experience, but they must also have weighed heavy on Rose Dugdale's mind and may help explain why she refused to be silenced. At her trial for the heist, she declared herself 'proudly and incorruptibly guilty.'

Rose Dugdale defiant on her way to trial

She applied her formidable mind to the problems of a world in flames, and concluded that the only way forward was to fight fire with fire and to challenge the state's monopoly of violence. I say that not to make mock of those who placed flowers in guns or chanted for peace, certainly not to denigrate those brave souls who marched and fell at Burntollet Bridge on the road between Belfast and Derry or on the road between Selma and Montgomery. I say so, simply because it's important to note that Dugdale's rebellion wasn't a generational one against her parents, or not that alone, but part of a generational 'lurch to the left' common to sentient rebels appalled by state terrorism in places as various as Argentina, Brazil, Chile, the Congo, Guinea-Bissau, Iran, Ireland, South Africa and Vietnam.

Amid all our rightly respectful modern talk of strong women, it's easy to forget that strong women like Elaine Brown, Kathleen Cleaver, Angela Davis, Bernadette Devlin, Bernadine Dohrn, Rose Dugdale, Delours and Marian Price and Ulrika Meinhoff were matching the Che Guevaras of the world stride for stride long before babble about 'dual-income relationships' and 'awesome dual-career entrepanoouers' bubbled up from the swamp of neo-liberal fantasy and before people accepted the ludicrous inculcated proposition that 'terrorists' are or were all cowardly crazed killers while the armies they oppose or opposed were all benign bravehearts acting for the common good.

'When the rich rob the poor it's called business. When the poor fight back it's called violence,' said Mark Twain. 'Our enemies call us terrorists... And yet we are not terrorists... The historical and linguistic origins of the political term 'terror' prove that it cannot be applied to a revolutionary war of liberation... Fighters for freedom must arm; otherwise they would be crushed overnight', said Manachem Begin when Haganah was fight British forces in Palestine.

Let's not be sucked down the plug hole, here, by the centrifugal force of arguments for or against the use of violence against violence but, rather, accept that Dr. King and Malcolm X pulled in the same direction, albeit it from different points. Whether or not you believe that, say, the ANC, the IRA or the Vietcong forced the forces of reaction to the negotiating table, the point is that those revolutionaries, at that time, were convinced by historic example and contemporary events that no social system or power structure commits suicide and that the world could only be amended by force of arms. A fully functioning historical imagination is required if we are to put ourselves in their combat boots and to understand Rose Dugdale and her times.

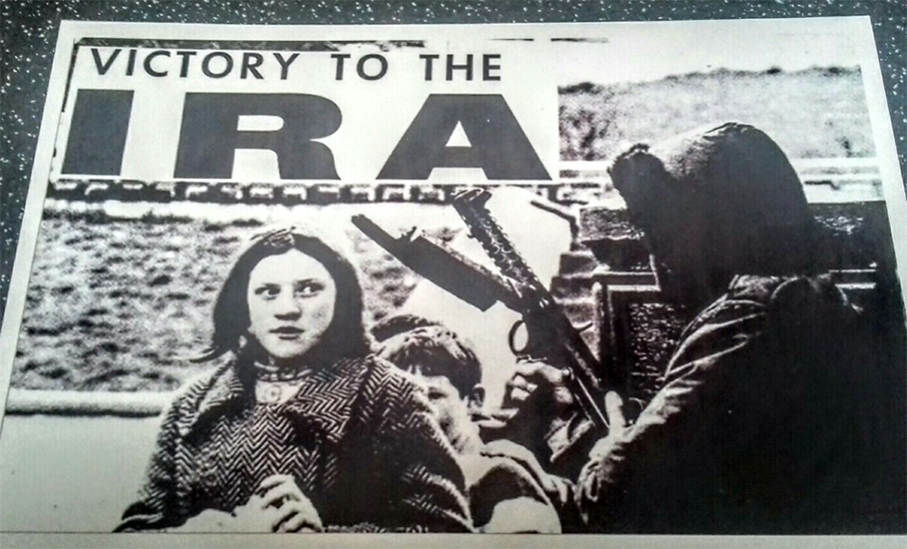

Delours and Marian Price

Despite its occasional missteps, Baltimore helps us in those efforts, if not to the extent that Arthur MacCaig's extraordinary The Patriot Game or Maurice Sweeney's brilliant I Dolours do. Its was through the latter, that I first heard the most indelibly horrifying story of the Price sisters' Aunt Bridie. In 1938, while just turned 27, she volunteered to collect a cache of IRA munitions from a safe house in Belfast. The explosive devices detonated as she tremulously lifted them from beneath the floor boards were they were secreted, shredding both her hands, taking out her eyes, and obliterating much of her face. The Price family tended to her wounds and cared for her, without public support in a house with an outside toilet, until her death. As young girls, the Price sisters regularly spoon-fed their chain-smoking auntie and placed cigarettes in her mouth. It's not hard to imagine how intensely that harrowing experience must have marked young Delours and Marian Price and stiffened their resolve to fight on for Auntie Bridie's cause.

As Patrick Radden Keefe says in his magisterial Orwell-Prize-winning investigation into the Troubles, Say Nothing, the Price sisters were active in an elite ultra-clandestine republican unit known as the 'Unknowns' that often did the movement's dirty work. Like the infamous 'Nutting Squad' formed to execute informers, it operated at one remove even from the cellular structure the Provos adopted to combat widespread British infiltration and penetration. It is likely that Rose Dugdale fought in a similar unit. She was certainly an unknown quantity with republican ranks and may have been allowed a free hand.

The shocking tale of Aunt Bridie alone serves as a stark reminder of the risks she took while expertly developing effective arsenals for the embattled Provos. Which begs the inevitable question, 'Ah, so how many people did she kill, directly or indirectly?' We might ask, in return, 'How many wars have you fought, for what and for whom?' Which, in turn, recalls Gore Vidal's response to a sensationalist hack who asked him if his first sexual encounter was with a man or a woman. To which Vidal replied, 'I don't know. I was too polite to ask.'

If Rose Dugdale was fortunate to evade Bridie Price's fate, she must have feared for her life at times and found the comparative peace of later life, when she taught working class Dublin kids science and English, hard to bear. Was she bored? Did she always yearn for former times? As Boa Night says, in The Sorrow of War, 'My past seems to enfold me and move with me wherever I go... My memories of war are always close by, easily provoked at random moments in these days which are little but a succession of boring, predictable, stultifying weeks.' We are indebted to Desperate Optimists for raising the questions touched on above and for refusing glib answers. Baltimore may raise more questions than it answers, but it is consistently riveting, expertly executed, and provides a fitting memorial to an enigmatic, extraordinary woman.

Irish Film Institute interview with Rose Dugdale conducted as part of the Mna an IRA series.

|