| |

'If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is: infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro' the narrow chinks of his cavern.' |

| |

William Blake, from Songs of Innocence and Experience |

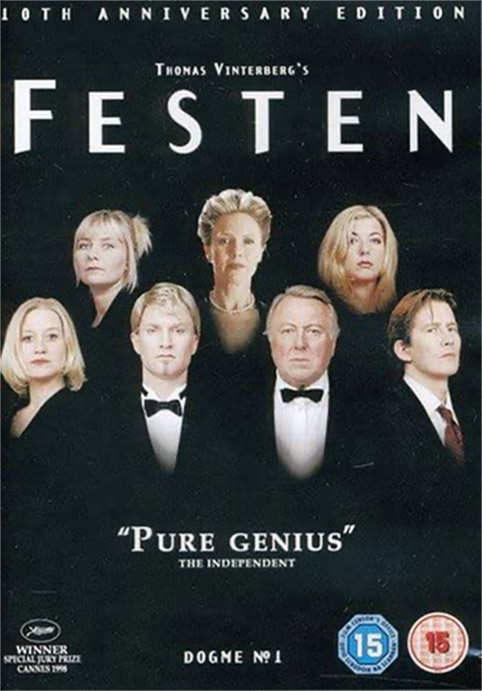

A quarter of a century ago, Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg launched their Dogma 95 manifesto, in a shower of leaflets, at an event to mark cinema’s centenary celebrations. Their stated aims were to redress a cinematic balance tilted toward big business and huge budgets, elevate innovation over standardisation, and ‘purify’ cinema – the better to appeal to audiences not ‘alienated or distracted by overproduction’. The Dogma manifesto, product of both inebriated high-spirits and high-minded seriousness, echoed earlier clarion calls for aesthetic and societal change such as Dziga Vertov’s Kino-Pravda manifesto of 1922, François Truffaut’s 1954 assault on ‘the Tradition of Quality’ in Cahiers du Cinéma, the Oberhausen Group manifesto of 1962, and, most obviously, Julio García Espinosa’s 1969 essay ‘For an Imperfect Cinema’. With its relatively modest budget of £4.5m Euros, Sturla Brandth Grøvle’s hand-held camerawork and understated cinematography, an impishly original script, its collective ethos and improvisatory modus operandi, Thomas Vinterberg’s latest film, Another Round, like his blistering 1998 debut feature Festen, reverberates with echoes of those echoes.

This year’s London Film Festival, a predominantly digital edition without precedent in the event’s illustrious history, ended on the weekend – with Another Round claiming the festival’s inaugural Audience Award for Best Film. By turns intoxicatingly exuberant and smartly astute, Vinterberg’s bittersweet gem is foregrounded in a salutary citation of Søren Kierkegaard: ‘What is youth? /A dream /What is love? /The dream’s contents’. Fittingly, the film focuses on four jaded, lovelorn schoolteachers who defy tedium, torpor and encroaching middle age by drinking increasingly prodigious quantities of alcohol. The friends rage against the dying of the light while doing damage to their livers and repeating, in unison, after B.S. Johnson, ‘I hate the partial livers. I’m an allornothinger’. Vinterberg’s film manifesto insists we live life to the full and take it in the round, perhaps with a round of drinks, certainly warts and all.

The film is ill-served by its anodyne English title; a trip to the golden triangle of Belfast-Glasgow-Liverpool suggests ‘Bevvied’, ‘Pished’ or ‘On the lash’ but this tragicomic gem deserves to travel far and wide so ‘Hammered’, ‘Four Sheets to the Wind’ or, simply ‘drunk’ (aptly close to Druk) might offered better concessions to commerce and Stateside marketeers. Actually, given the film’s emphasis on solid bonds of friendship, the breeze blowing into it from Vinterberg’s 2016 film The Commune; and the undoubted influence of Lukas Moodysson, perhaps Together might have worked well. If the title did the film no favours, Vinterberg’s cast, particularly Mads Mikkelsen, make it dance and sing. Like all the best directors, he knows how to get the very best out of very talented actors. In common with, say, Robert Guédiguian and Pablo Larraín, he is able to replicate the palpable sense of camaraderie and trust inherent in a script by repeated use of the same ensemble cast. As in The Hunt, he works intuitively with old friends and colleagues: Mads Mikkelsen, Lars Ranthe, (both of whom also appeared in The Commune), Thomas Bo Larsen (who also appeared in Festen), Annika Wedderkopp, and Susse Wold.

![The Commune [Kollektivet] poster](../../pix/a/an/anotherround_02_kollektivet_pstr.jpg)

Having been raised on a commune himself, Vinterberg no doubt received early lessons in the pitfalls and possibilities of collective endeavour and the film is imbued with a wonderful sense of an often fragile all-for-one-and-one-for-all togetherness. One particular scene, which winks at the café dance sequence in Godard’s Bande à part, sees the four exhilarated and liberated friends dance to soul-funk classic ‘Cissy Strut’ by the Meters. It speaks volumes of a happy cast and crew. Vinterberg deftly teases out shades of dark and light by again working productively with co-writer Tobias Lindholm – with whom he’d worked on the light-hearted comedy The Commune and the darker-hued The Hunt. Their script is perfectly paced, sagacious and quick-witted.

If the Dogma manifesto was simply a provocative signal sent by rebellious cinephile youth, Another Round sends smoke signals to battle-hardened, world-weary braves. Non-Dogma-tic history teacher Martin (Mads Mikkelsen) is weary of his subject and of his life. His students fear for their academic futures and his long-suffering wife, Anika (Marie Bonnevie), fears for her sanity. When Martin asks Anika if he’s become boring, a heavy silence hangs in the air before she admits he’s not the man he once was. Later, she says, ‘Don’t you see our problem is that you’re never really present? You’re completely invisible’. At a 40th birthday party dinner, philosopher Nikolaj (Magnus Millang), the musical Peter (Lars Ranthe), and sporty Tommy (Thomas Bo Larsen), sense Martin’s listless despair and persuade him to try a nip or two of vodka. Nikolaj recounts Norwegian psychiatrist Finn Skårderud’s – since-repudiated – theory that we are all are born with a disastrously low blood alcohol content of 0.05%, which prompts the friends to hatch a plan to avert their mid-life crises. Churchill said, ‘I never drink before breakfast’ but the friends take their lead from Ernest Hemingway: they vow to drink daily but only until eight in the evening. Taking a leaf, too, from Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception, they agree to gather evidence of the ‘psychological, verbal motor, and psycho-rhetorical effects’ of alcohol, for ‘a study of increased social and professional performance’. As they test the limits of their commitment to change, their alcohol endurance levels, and their friendship, they become their experiment.

Initially at least, all goes well. Energised, invigorted and fully alive once more, Martin takes his family on a camping holiday, during which he and Anika make love in their tent, for the first time in a long, long time. His performance at school improves exponentially too. He offers his students brilliantly inventive tests. ‘There’s an election with three candidates, so who do you vote for? No 1: He’s partially paralysed from polio. He has hypertension. He’s anæmic and suffers from an array of serious illnesses. He lies if it suits his purpose and consults astrologists on his politics. He cheats on his wife, chain smokes, and drinks too many martinis. No 2: He’s overweight and he’s already lost three elections. He’s had depression and two heart attacks. He’s impossible to work with and smokes cigars non-stop. And each night as he goes to bed, he drinks incredible amounts of champagne, cognac, port, whisky – and adds two sleeping pills before dozing off. No 3: He’s a highly decorated war hero and treats women with respect. He loves animals, never smokes and only has a beer on rare occasions. Who do you vote for?’ The students vote for candidate No 3., only to discover that they have cast aside FDR and Churchill and elected Hitler!

The teaching techniques of the others improves too. Peter transforms his discordant singing class into a heavenly choir of angels and calms the nerves of a student experiencing blind pre-exam panic – by slipping him some alcohol. In an echo of Moodysson’s Together, Tommy coaches his junior football team to victory, even engineering a slick move in which a bespectacled, bullied kid is delightfully transformed into a respected, befriended hero by a winning goal. After Peter plays a recording by pianist Klaus Heerdorf, who performed best in a state of equilibrium between sobriety and inebriation (neither too much nor too little), all four agree to increase their drinking to the point of ‘ignition’ – at which point things inevitably take a turn for the worst. Martin crashes face-first into a door jamb and later scars himself in a drunken fall, his relationship disintegrates, while Tommy takes a tumble in the off-license, Peter wets his bed, and that’s just the start. No longer an effervescent ode to the joys of libation, intoxication and male friendship, the film twists and turns around the unspoken menace of addiction, skirting it slightly but implying it always.

A montage of found footage clips showing hammered world leaders drives home the point: ‘Mutti’ Merkel guzzles from a stein, Boris Yeltsin totters next to Clinton, Breshnev slurs his words during a televised address. ‘We’re not alcoholics,” says Nikolaj, ‘we decide when we want to drink. An alcoholic can’t help himself’. As the film darkens and deepens, denial heralds addiction, which seizes its victims by the throat, and which subsequently reveals itself in injury, hidden bottles, myopic dissolution and obsessional consumption. Rehab, the twelve-step programme and the Fellowship fast become the only alternatives to ‘jails, institutions or death’. Before the film ends, each of the four friends must choose between those stark options. A suicide and a funeral announce that they’ve reached their endgame, even if friendship holds firm.

Vinterberg experienced a haitus and a kind of crisis of faith after the collapse of the Dogma project. We might suppose he occasionally turned to drink, perhaps he took against it. Be that as it may, he has said, he intended Another Round to be a celebration of life not alcohol, an attempt to reclaim ‘the irrational wisdom that casts off all anxious common sense’. If the film issues demure warnings about the dangers of addiction, its overriding theme is, to paraphrase Kafka, that alcohol can be the axe that shatters the frozen sea of our souls. We might paraphrase Victor Shklovsky’s aphorism on art too, and suggest that alcohol ‘exists that one may recover the sensation of life; it exists to make one feel things, to make the stone stony’. Cinema, humour, friendship, music, literature, philosophy and sex can also be such axes and can help us feel things – as can films like Another Round, containing, as they do, all those life-affirming ingredients. In one of Nikolaj’s classes, a student reads another keynote quote from Kierkegaard: ‘To dare is to lose one’s footing momentarily. Not to dare is to lose oneself’. Although there are casualties along the way, the men have sloughed off sloth, dared to live and reconnect with the joy of living, transformed their students’ lives, rebuilt fractured relationships, and reconnected with their youthful selves. It’s almost a happy ending. It feels like a happy ending, as professionally trained dancer Mads Mikkelsen leaps and pirouettes on a harbour front in the closing scenes.

The film pulls off the rare trick of effortlessly moving back and forth between captivating comedy and dark drama. It strides elegantly forward, perfectly in-step with the sure-footed poise of a director completely at home with his cast, his medium, and his environment. Something is rotten in Vinterberg’s native Denmark – one of the world’s most prosperous, well-ordered and equitable societies. It’s not always sunny there, existential angst looms large in paradise, and Another Round offers a lighter look at the darker side of even the most comfortable of lives. The Danish word 'hygge', similar to the equally untranslatable German word 'Gemutlichkeit', contains a compacted sense of the camaraderie, cosiness, comfort, humour and (often drunken) hospitality; all essential to peoples who regularly encounter dark nights and dark thoughts. That delicious Danish word also implies the need for the kind of earthy and earthed human solidarity the film’s four friends, and the actors who play them share. Therein lies the film’s precarious beauty, at once parochial and universal.

Much of the film’s more subtle moments of humour are distinctly Danish though. When Anika says, ‘I couldn’t care less if you drink with your friends. That’s not the point. This entire country drinks like maniacs anyway’, we can hear Danish giggles roll around the cinema... or lounge. A similar joke occurs after Martin shows his students images of Ulysses S. Grant, Churchill, Hemingway: ‘What’, he asks the class, ‘do you have in common with them? You drink like pigs. Every week. All year round’. Young Danes are driven hard and drive themselves hard. Their drinking culture, often alluded to in the film and carried forward into adulthood, grants a slither of space to an anarchic freeform resistance to the quotidian demands of career and commerce; a point well made in The Commune, Together and Another Round.

The quotes from Kierkegaard recall, and may allude to a great joke by that Danish master of mirth Carl Dreyer that bears repeating. In Dreyer’s sublime film Ordet, a new Parson visits the Borden family and is shocked by the behaviour of mad Johannes, who introduces himself as ‘Jesus of Nazareth’. Later, the Parson politely broaches the subject of Johannes's mental health with the latter's brother, Mikkel, who says simply, ‘Something happened’. The Parson asks, ‘Was it love?’ To which Mikkel replies, "No, no, it was Søren Kierkegaard’. It’s a dry, subtle joke at Dryer’s own expense aimed also at a dour Danish tradition of sober, solemn philosophical seriousness. Vinterberg’s allusion to Finn Skårderud may also be an ‘in-joke’ as the heavy drinking Danes have a friendly rivalry with the Finns, whom they consider a nation of lushes.

The film’s mischievous wit and comic mood sits comfortably with its darker, more meditative observations on the human condition and beleaguered masculinity. In Another Round, Martin, having reduced his students to tears of laughter with his instructive joke on the three electoral candidates, says, ‘Focus! It’s funny, but there’s a point to this, which is important and which I hope you’ll understand some day: the world is never as you expect’. Vinterberg – who lost his teenage daughter, Ida, while making Another Round – understands that. He knows that life is short. He has gifted us with a film for the ages which, by deftly melding irreverent humour and sober seriousness, reminds us that our days are few, that we have just so many hours and so much sunlight, before it all vanishes. Vinterberg’s life-affirming film yells, ‘We have nothing to fear but fear itself’. Down with the partial livers!

I’ll close on a dark aside – we’re enduring a pandemic after all – and point to a slight cloud hanging over the LFF Audience Award justly given to Another Round. Whatever one thinks of awards and award ceremonies, it was pleasing to see Cathy Brady scooping a £50,000 filmmaker bursary award for her superb psychological drama Wildfire; a pity, though, that her co-star, fellow-Irishwoman Danika ‘Nika’ McGuigan (daughter of boxing great Barry McGuigan) was not honoured. She died, aged just 33, while making the film, so her starring role in the film was her first and last. In the TV drama First and Last, another Irish actor, Ray McAnally, played a retired civil servant, Alan Holly, who’s determined to walk from Land’s End to John O’Groats to prove he’s still alive and not a dead fish. Soon after that point in the film in which Holly has a heart attack, McAnally died of a heart attack himself. The drama was filmed again, with Joss Ackland taking over McAnally’s part, but McAnally received a posthumous BAFTA award. Here’s to Ray, Ida, and Nika. Cheers!

Hillel Einhorn on happiness: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f6BALquQ_Bo

|