| |

"In this part of the world, unfortunately, the normal is the exception. It is the irrationality and the abnormality, the racism and the extremism that is prevailing today

in the Holy land which has been taken by the Devil." |

| |

A

videophone message from Gaza |

The

Israeli-Palestinian conflict is one that can provoke strong,

one might even say extreme reactions. I myself have had

to step in to stop a shouting match on the subject from

developing into a punch-up, and have listened to otherwise

perfectly rational people make outrageously sweeping statements

about one side or the other. One of the most frequently

repeated comments casts every Palestinian as a potential terrorist,

a view given undue weight by the might of the Israeli state and

its influence in the West. It is this belief that was

at the heart of the decision by the Israeli government to

erect a 681 kilometre barrier along the West Bank to divide

the Israeli and Palestinian population of the region. The

project is a long term one that will take many years to

complete and is being constructed from a mixture of interlocking concrete sections,

vehicle trenches and densely packed barbed wire. By January

2006, three years after the project commenced, approximately

31% was completed and a further 31% was under construction.

Supporters of the barrier refer to it as The Fence. Its

opponents call it The Wall.

Documentary

film-maker Simone Britton uses her Jewish-Arab background to examine the nature of the barrier and its effect on

the population living around it from both sides of the divide.

In the process, she encounters some unsurprising attitudes,

from those on the Palestinian side who equate it to a prison

wall, to the claim made by director general of the Israeli

Ministry of Defence General Amos Yaron that it is a necessary weapon against

Palestinian criminal and terrorist activity. But Britton also

uncovers some intriguing examples that kick against the

expected, most memorably the Arab construction workers who

are helping to build the barrier, grateful for the work

in an area with few job opportunities and no social security.

The

film kicks off in captivating fashion with a close to three

minute track along a lengthy section of the wall that has

been fabulously decorated in a variety of artistic styles,

while the off-camera voices of Israeli children explain

to the enquiring Britton the purpose of the wall. "They

shoot Arabs from here," says one, only to have his

friend say, "No. Arabs shoot at us." "Who

shoots at who?" Britton pertinently asks, but gets

no reply. It is just such casually delivered comments that

provide some of the film's most insightful moments, as pedestrians approach the film-makers and pass comment on the barrier

and its impact on their lives.

Often

arrestingly shot, the editing pace seems almost too leisurely

at times, with shots held for far longer than would normally

be expected and not always with obvious purpose, creating

the sense of an hour-long film that has been stretched out

to 90 minutes. Actions and places are observed, and lingering

on them sometimes creates the sense of a point being laboured. But more often than not the message is conveyed

precisely by letting the shot roll on uninterrupted, as

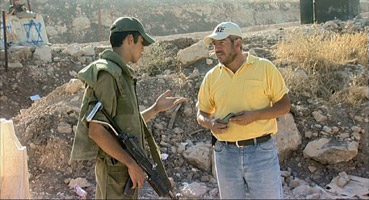

with the Israeli patrol guard who checks

the identity of Palestinians attempting to pass through

the barrier but who ends up stopping a succession of Israeli

citizens leaving an area in which they should not have been in the first place and

admonishing them with steadily increasing severity.

Britton

and her crew never appear on camera but intermittently become

part of the story they are telling, as they are questioned

by passers-by, challenged by a soldier only after they have

spent some time filming him, and asked if they feel unsafe

working in the area by an Israeli who believes that the barrier

is an ultimately ineffective waste of money. It is he who

brings the reality of suicide bombings down to a personal

level. "Have you ever found yourself standing next

to a bus?" he asks Britton. "When you stand next

to a bus, pray for the light to be green. That's what I

do." Anyone with even a passing knowledge of the area's

troubles will understand the implications of that statement.

The politics of the situation are never really engaged or

even introduced, and a degree of knowledge of the conflict,

the locale, and even the wall itself is assumed. The film

focusses not on the wider issues, but on the barrier and those living within its metaphorical shadow. Although

largely even-handed in its range of interviews, the wall

is never really seen in a positive light, making large profits

for an Israeli concrete manufacturing firm but robbing land

from Palestinian farmers, on whose side of the divide the

barrier has been constructed. Neighbourhoods find themselves

cut in half, frustrating even those on the Israeli side

who would like to get to know those who live just a few

metres away, while others find their route to work now blocked.

One Palestinian man even tells of a social divide within

his own family, separating those who have Jerusalem ID cards

from those who do not. It is perhaps a little ironic that

the most passionate and reasoned case made against the social

injustice of the barrier is made not by a penniless West

Bank inhabitant, but a comfortably-off Israeli.

Although Wall tends to nibble where I wish it would

bite, these nibbles are numerous and cumulatively effective.

Even Amos Yaron presents the case for the barrier in increasingly

unconvincing terms, becoming gradually agitated with the

questioning and detailing an overkill of security measures

that are shown to be completely ineffective when locals

are filmed moving freely and easily across the divide. But it's the small moments, the lingering

shots that at first seem a little too lingering,

that really hit home – the landscape slowly blocked out

of the picture by concrete wall segments, the village dominated

by an armed watch tower that sits on the hill above, the

segment of wall that has been lovingly painted to resemble

the more tranquil scene that lies beyond it.

Britton

ends her film on a repeat of the opening shot, but on a

section of the wall where there are no paintings to beautify

this concrete and wire exercise in social division and control,

only scrawled graffiti. Here the wall is already in disrepair,

patched up by concrete blocks and topped by ragged barbed

wire. It is here that the dour reality and ugliness of the

project is most poetically expressed, and as we watch one

girl effortlessly scale it and an old woman holding her

hand against the concrete as if attempting to reach beyond

its confines, the cruelty and pointlessness of the multi-million

dollar construct is quietly but very effectively made clear.

Shot

on what looks life DigiBeta or High-Def, the transfer has

been taken straight from the digital master and is frankly

pristine, with excellent colour, contrast and detail and

solid black levels throughout. This really does justice

to Jacques Bouquin's eye-catching and tellingly framed compositions.

Yes, digital video can be beautiful too.

There

is no call for a flashy 5.1 soundtrack here and the Dolby

2.0 stereo track serves the film well, reproducing the dialogue,

location sound and music with impressive clarity and dynamic

range.

The

are two conversations with Simone Britton, the first between

her and Palestinian filmmaker Elia Suleiman (30:31) in which the two discuss in English the film, its

structure and its purpose, and Britton talks in detail about

her views on the Israeli-Palestinian situation, as well

as passionately explaining just why she cannot imagine ever

making a fictional feature. In the second Britton talks

with another Palestinian filmmaker, Michel Khlefi (29:11), about the film and the underlying social politics

of the wall and the conflict. A key revelation occurs at

the start when Britton, who shot the film in 2003, states

that if she was making the film now it would be far more

serious due to how far she believes things have deteriorated

in the region. He views on the conflict are again made plain,

especially when she suggests that the wall was built because

of "the Israeli disease." She also explains how

she came to make the film, and the two discuss the experience

of growing up in different cultures in the same country.

Pleasingly, there is almost no overlap between the two interviews,

both of which are useful companions to the film, although

I would suggest that both Britton and Suleiman smoke too

much for their own good. The Khlefi-Britton discussion is

in French with English subtitles.

A

stern whisper of protest rather than a cry of righteous anger and a bit too

leisurely paced at times, Wall nonetheless

succeeds in humanising an issue usually discussed in purely

political terms. That it takes sides will no doubt prompt

those who do not agree wholeheartedly with Britton's viewpoint

to dismiss the film as propagandist, but the points made

are all valid and these voices have as much right to be

heard as any other. Whether the film will find an audience

on DVD is another matter – there are few surprises here

for those already familiar with the politics and the situation,

while the lack of background information does not make it

the ideal introduction to the complexities of the Israeli-Palestinian

conflict. But it is a worthwhile and involving documentary,

and could well prove a useful tool for those looking to

clarify to others a situation in which the human issues

are too often lost under the weight of sweeping statements

and simplistic judgement. And with the situation in the

Middle East as volatile as ever and the American government

considering a similar barrier between its southern border

and Mexico, this release could not be better timed.

|