|

It's a little scary how those in positions of power are able to employ numbers and statistics to distance themselves from the human consequences of their actions. Just last week, the homeless charity Shelter produced a damning and frankly horrifying report about the conditions of the private rented accommodation in which many of those at the bottom of the social ladder are being housed. If you've somehow not heard about it then hunt it out, read it, and hang your head in sorrow that this could be allowed to take place in what we like to call a civilised society. Yet the official government response was not to pledge immediate action to right this terrible wrong, but to issue a statement claiming that over 83 per cent of those in such accommodation are satisfied with their living conditions.* By doing so they avoided putting a human face on the suffering and reduced it to a statistic, one that could be effectively dismissed because it was a minority, in the process absolving the ruling authority of affirmative action against the slum landlords they seem so keen to protect. And by quoting a percentage they can also transform a sizeable number into a seemingly insignificant one.

This reduction of people to numbers is as old as history itself and has found particular favour in institutions where individuality and free thinking is actively discouraged, hence its use in years past in everything from prisons and borstals to the armed forces. It's a process that depersonalises and strips an individual of an important aspect of their identity, replacing it with label that could have been banged out by a machine and renders them part of a faceless collective. There's a damned good reason that in Patrick McGoohan's masterful allegory on individuality verses the state, The Prisoner, the residents of The Village are referred to only by their assigned number.

Numbers and statistics play a key role in Transport from Paradise [Transport z ráje], a gripping, intelligent but little seen 1963 film directed by Czech director Zbynĕk Brynych and co-written by occupation survivor Asnost Lustig, based on his own stories. Set in the Terezin (renamed Theresienstadt) ghetto during the German occupation of Czechoslovakia in WW2, the film is bookended by the arrival and later departure of visiting SS official, General Knecht (Jindřich Narenta), who has come to inspect the work of the incumbent Nazi officers. Ostensibly overseers of a self-governing Jewish community, these men are effectively monstrous clerks, keeping strict records of the inmates and the daily death rate, and processing names and assigned numbers of those who will be hoarded onto the next train to Auschwitz. This obsession with records and order extends to the inmates' luggage, which is taken from them before transportation, then carefully numbered and labelled and stacked in a manner that transforms the storage facility into a bewildering maze.

The process of preparing the ghetto inhabitants for transportation is one the Nazis oversee but technically absolve responsibility for, passing the job of selecting who is to board each train to Town Council Chairman David Loewenbach (Zdeněk Stěpánek). We're at a stage in the war when the terrible truth of what this journey will mean is only just starting to filter through to the ghetto inhabitants, and when the defiant Loewenbach refuses to put his signature on the latest list of names, he is thrown in a cell (where he will receive 'special treatment') and the more compliant Marmulstaub (Čestmír Řanda) is appointed in his place. This refusal to transport people to a camp at which they will be gassed without the signature of their own elected representative is both the height of bureaucratic absurdity and an insidiously cynical ploy that to an untrained observer would appear to make the Jews complicit in their own destruction. And at this point the Nazis seem keen to combat rumours that they have blood on their hands in their handling of the so-called 'Jewish question' – even as they are sending others to their deaths, they are shooting a propaganda film in which Jews of several nations speak of their contentment and the fine treatment they have received at the hands of their oppressors.

Waging a small propaganda war of their own are a small number of inmates who – a tad ironically – print leaflets and posters urging non-cooperation from within the maze of confiscated suitcases. These are characters we rarely encounter in Holocaust themed films, a young and almost Bohemian group who seem determined to make the best of an appalling situation and whose spirit is captured by the jaunty song on the soundtrack that counterpoints the dark deeds that are unfolding around them. Although seemingly buried for much of the film, their apprehension over what lies ahead is brought home in one of the film's most touchingly affecting scenes when, on the night before they are to be transported, they each avail themselves of the sexual favours of willing local girl Lizinka. It's a gentle and subtly handled scene in which the sexual encounters are signalled by nothing more than the sound of curtain being drawn, while the camera remains with those who await their turn for both this last taste of female affection and their uncertain fate.

Our present knowledge of the details and sheer scale of the horrors that did unfold allows director Zbynĕk Brynych to sidestep exposition and leave it to us to interpret the true meaning of seemingly inconsequential words and actions. Sometimes the smallest of details can hit home – that all Jews were required by the Nazis to wear a yellow star on their clothing is now well known, but the image of a similarly adorned dress suit in a tailor's shop window for some reason really got under my skin, the suggestion being that even clothing should be segregated because of its intended market. Perhaps most discomforting of all is the Nazi-enforced ruling that when addressed by an officer, all residents must respond by loudly identifying themselves as "Jewish pig" before stating their name, a bullying tactic that massages the Nazis' ridiculous conviction of their racial superiority.

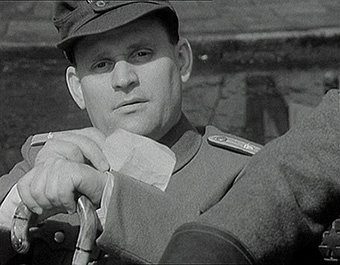

That the German officers are presented as amoral monsters is perhaps unsurprising, but here their real crime is not physical brutality, of which there is surprisingly little, but their shocking indifference to the humanity of those they see only as statistics to be correlated and checked and ultimately disposed of. The only one shown dishing out violence is the sadistic Obersturmfüher Hertz (Ilja Prachař), an incumbent officer who clearly relishes the power his position gives him over people he would be loathed to call his fellow men. His driver Binde is a very different story, a fluent Czech speaker whose history we can only guess at (was he a local who joined or was pressured to join the Nazis, or an educated German drafted into the army?) and whose unhappiness with his assigned duties and contempt for his superior officer is subtly written all over his face (actor Jiří Vrštála is excellent in this regard). His sympathies clearly lie with the people he is reluctantly helping to oppress, and this twice sees him disregard orders, first when he lets a pleading prisoner go free, and a short while later when shoots a fleeing woman who begs that she be killed rather than face the torture Binde has been ordered by Hertz to inflict upon her.

All of the elements come together in the downbeat but compellingly handled final act, as the two thousand selected for this latest transportation – including almost everyone we have come to know and like – are lined up in a field in preparation for their departure. Here the Nazi obsession with order and numbers sees them called out individually and forced to run to the front irrespective of their age or infirm health, and at one point an interruption sees the process restarted from scratch. As cinematographer Jan Čuřík's camera seeks out expressions of fear, longing and sadness and the hands of couples clasping each other in desperation, the emotional effect is quietly devastating.

As both the train and Knecht depart and the remaining Nazi officers cheerfully send an adjunct out for champagne, the simple two-tone whistle that signalled the train's early film arrival becomes a mournful call to death, which is then underscored by the rhythmic squeak of the adjunct's bicycle. This simple but haunting twin aural motif, speaking as it does of transport and mechanisation and the terrible use to which both have been put, is left to play out on the soundtrack even after the credits have rolled. It's an appropriately haunting ending to a genuinely remarkable and uniquely toned film, one whose message about the potential consequences of reducing the human experience to numbers and statistics is as sadly pertinent as ever.

A solid enough transfer from an imperfect source, the 1.33:1 image here is sometimes peppered with dust spots, the occasional scratch and the odd spot of slightly more serious damage. The digital master has also been subjected to some visible edge enhancement, but still displays a good level of detail and boasts a very reasonable contrast range and solid black levels, with daylight exteriors coming off best.

The Dolby 2.0 mono soundtrack does sometimes show its age in the narrow dynamic range of the dialogue and that early song, but inmate Dany's guitar strumming during Lizinka's visit is surprisingly clear and full sounding. As with the picture, some minor damage remains and there are a couple of spectacular pops, but otherwise this is a serviceable job.

No on-disc features, but there is a Booklet featuring a fascinating essay by prize-winning playwright and author Roy Kift detailing the history of the Theresienstadt – he has written two plays about it – and the ways in which the film differs from historical fact and the reasons for the changes.

Another superb rediscovery by Second Run, one whose picture imperfections fail to detract from what is a gripping and important example of Czech New Wave cinema that also happens to be one of the best Holocaust themed film dramas I've seen. Highly recommended.

* http://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/feb/26/homeless-shocking-rat-infested-conditions

|