|

Anyone

familiar with the theories of Structuralism will have encountered

the concept of binary oppositions, the notion that human thought

and even culture is organised as a series of diametric

opposites. This is most evident in religion, where notions

of good and bad, heaven and hell, God and the Devil offer

no middle ground, just a straight choice between paths to

damnation or salvation. Once upon, a time folk tales used

to be built on similarly unfussy foundations – witches were

ugly and evil, princes were handsome and brave, princesses

were beautiful and pure, and dragons were monstrous and

had to be slain for their sins.

Such

oppositional notions made their way into early cinema, notoriously

in the black hat/white hat villains and goodies of early

westerns. Times change, and long ago the notion of defining characters in such extreme and uncomplicated terms seemed

archaic and almost childishly simplistic. That doesn't stop

people doing it, of course – tabloid newspapers make daily

headline news out of casting people as cartoonishly evil

or tear-jerkingly saintly, and let's not forget the ease

with which certain politicians can cast an entire nation

as monsters with few carefully chosen words of rhetoric.

Astonishingly, people still respond to it like programmed

lemmings, waving their flags and calling for the destruction

of entire peoples or religions without really knowing why. Hell, maybe those Structuralists

have a point after all.

This

societal attitude is still sometimes reflected in Hollywood

movies, which too often like their bad guys to be impossibly

evil and preferably foreign, and their good guys to be young,

handsome, clean shaven and all-American. Which is all well

and fine for the tabloid crowd, but a bit much for those

of us that expect our movie characters to have, well, some

depth. I like to include myself in that particular clan,

but for some reason all of this flies out of

the window the moment I sit down in front of a martial arts

film. It remains to this day the one genre whose rules

demand that the good guys will almost always be sweetly

innocent and the bad guys can be as evil and one-dimensional

as you care to make them.

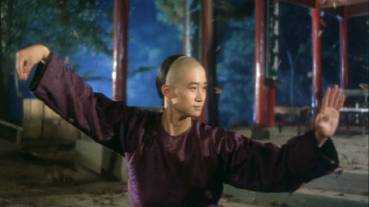

Tai

Chi Boxer is a perfect case in point. Now this

is not a work from the 1970s, where such simplistic plotting

was an expedient short-cut to the punch-ups the punters

had handed money over to see, but from 1996, a mere four years before the altogether more sophisticated

characterisations and plotting of Crouching Tiger

et al. And yet our hero Jackie is the very

personification of smiling and innocent goodness – he studies

hard, treats people with politeness and respect, falls for

the beautiful girl, learns to dance, and is even magnanimous

towards his rival in love. The bad guy, however... well

let me list the things that mark Mr. Smith as a kung fu

movie baddie:

- He

deals in drugs;

- He's

foreign (English, in fact);

- He

dresses in western clothing (a tuxedo, no less);

- He

has a beard;

- He

scowls at everyone;

- He

threatens nice people;

- He

kills one of the good guys;

- He's

a dangerous fighter;

- He

uses a gun when others are restricted to fists and feet.

Simplistic

though this may seem, some of it is at least rooted in cultural

history. Tai Chi Boxer is set in the 1830s,

shortly before the notorious Opium Wars between England

and China. Opium was widely used in China at the time and was not a home-grown vice but one imported into the country by

the English, and part of a trade disagreement that in 1840

led to England sending in their warships and pounding the

hell out of the technologically inferior Chinese. In 1842,

China was forced to sign the Treaty of Nanking, which was

weighted heavily in England's favour and gave them almost

ludicrously advantageous trading powers. It remains an inglorious

moment in English history (we've got quite a few of these) and a

painful memory for the Chinese. And thus our bad guy, with

his English nationality, western clothing and ruthless drug

trafficking, taps into a moment in cultural history where

he really can be seen as a bastard. Even the gun is representative of English military

superiority against the more honourable and more elegant

fighting methods of the Chinese townspeople. That doesn't

make him a sophisticated character, not by a long

shot, but does at least provide some context for his inclusion.

Other

historical elements are also woven into the plot, some of

which reflect more recent attitudes and events. Jackie

determines to free his future father-in-law and most of

the police force from their drug addiction through a combination

of cold turkey, exercise and spiritual purity, while the

western educated students who dress in blazers and boaters

and have cut of their queues (long pigtails whose adoption

was enforced by the Manchu rulers as a sign of dynastic

loyalty), distribute leaflets promoting democracy, itself

reflecting events in modern China that led to the Tianenman

Square massacre in 1989.

All

of which provides some interesting layering for a film that

is nevertheless, like all genre works, still primarily about

the fights and the triumph of good over evil. And if it's

the fights you came for then you'll have few complaints.

The Tai Chi fighting style featured here has a grace and

elegance that the camera loves, especially when delivered

by the young Jacky Wu, co-director and fight choreographer

Yuen Woo-ping's new young hopeful who has yet to find the

widespread success of predecessors Jackie Chan and Donny

Yen. Which is a shame, because despite his ever-present

wide-eyed smile and almost infuriating optimism, he leaps

and moves and kicks with the best of them, and brings an

energy and almost balletic grace to the fights that could

well prove as distinctive a calling card as Tony Jaa's Muay

Thai. And he's not alone – 20-year genre veteran Yu Hai,

kick boxing champion Billy Chow and self-taught British

film fighter Darren Shahlavi all get to show their stuff

in a series of breathlessly inventive fight sequences, which

build to a terrific final warehouse battle in which East

and West go head-to-head in a dizzying display of flying

fists, feet, bodies and wood.

This is all impressively showcased by some eye-catching

camera placement and sometimes kinetic hand-held cinematography

that plants you right in the middle of the action. On the

commentary track, Bey Logan remarks on the lack of insert

shots due to the low budget and hurried shooting schedule,

but I found it refreshing to see fights playing out without

being broken up into a blizzard of high-speed cut-aways,

better showcasing the awesome skills of Yeun Woo-ping and

his performers.

At

the end of the day, Tai Chi Boxer is martial arts actioner,

and on that level it really delivers. Just as well really,

as it would struggle to get by on a script that more than once barks the obvious – halfway through their first screen fight,

Jackie's good friend asks him how they can take on so many

attackers, only to be told cheerily that they should "use

the martial arts we secretly learned!" Oh, right.

1.78:1

and anamorphically enhanced, the picture at times looks

and plays like that of a film from the 1970s, the

daytime exteriors having a very slightly washed-out look,

though scenes set either inside or at night look fine, and

at its best the contrast and colour are very good. As usual

with Hong Kong legends transfers, the print is virtually

spotless.

If

the picture has an occasionally retro feel, the soundtrack

harks back even further, having a limited dynamic range

and sounding almost tinny in places. Despite being a 5.1

track, the dialogue and sound effects are confined largely

to the centre speaker, through music tends

to be spread wider. Clarity is never a problem, though. There

is also an American English dub, which is of similar quality.

The

expected and welcome Commentary

by Bey Logan is loaded to the gills with information on

the Thai Chi fighting style, the cultural and historical

background to the film, co-director and fight choreographer

Yuen Woo-ping, and the careers of the lead actors, half

one whom he seems to know personally. As ever, it's not only

a fascinating and sometimes entertaining listen, but an

essential companion to the film.

The

two Trailers are the UK Promotional (1:47), which is sound effects and dialogue free, and the

Original Theatrical (2:21), which has even tinnier sound

than the feature. Both are anamorphic widescreen and in

good visual shape.

There

are two Interviews, the first

with the film's love interest, Christy Chung (22:43), who

talks about her role in the film and her work with such

genre luminaries as Jet Li, Jackie Chan and Stephen Chow

(who she once asked to marry her and here pleads for a positive

response), as well as her admiration for Michelle Yeoh,

her roles in other martial arts films, her photo book Feel,

and getting back to her career after the birth of her daughter.

There are also a collection of interview outtakes and cheery

fooling around at the end, which is topped off with an on-camera

reprise of a joke about female orgasms first heard on the

commentary of Red Wolf. The

second is with Darren Shahlavi (40:22), who plays the film's

English bad guy, Mr. Smith. This is a welcome feature after

the extensive information supplied on him by Bey Logan,

who was instrumental in getting him involved in the Hong

Kong movie industry and whose house Darren used to visit

to dub fight scenes from his tape collection. Running for

a decent length, this is a consistently interesting interview,

not least because Shahlavi is clearly a genuinely nice guy

and a fine storyteller, outlining how he came to work in

the Hong Kong film industry and providing some background

on Yuen Woo-ping's working methods, as well as some engaging

on-set anecdotes, creating the impression that hard work

though it may be, working on Hong Kong action films is one

of the world's best jobs. The interview is interspersed

with behind-the-scenes footage shot on Shahlavi's own camcorder

by whichever crew member was free at the time, and is used

effectively to provide illustration to his storytelling.

Shahlavi also talks about the original but ultimately unused

ending, which is illustrated with production stills.

Both

interviews are shot on DV in anamorphic widescreen and look

fine, but the sound has been recorded with the levels on

automatic, resulting in a couple of moments when it drops

out and slowly recovers after a particularly loud word from

the interviewee.

The

Christy Chung Photo Gallery consists

of a series of reproductions from Christy's photo book, Feel.

I suspect Bey Logan may be keen on this extra, being of the

opinion (along with FHM magazine) that she is "the

sexiest woman in Asia."

Behind

the Scenes Montage (1:40) is comprised of

footage from Darren Shahlavi's camcorder record of the warehouse

climax shoot, set to music from the film. Interesting in

itself, it's pretty damned short given the footage that

must have been available, and in truth there's probably

more included in Darren's interview.

Behind

the Scenes Photo Gallery consists of 51 production

stills, including those of the unused ending discussed in the Darren

Shahlavi interview, all reproduced at a good size.

Timing,

it is said, is everything, and in this respect luck was

not on Tai Chi Boxer's side. Released in

Hong Kong when interest in the second wave of martial arts

actioners was on the wane, it bombed at the box office and

failed to launch Jacky Wu's career with the hoped-for bang.

But for fans of martial arts cinema it has a lot going for

it, especially in the fabulously staged, turbo-charged fight

sequences. As Bey Logan rightly states, they showcase the

remarkable Yueng Woo-ping at pretty much the top of his

game.

|