| "What you have loved remains yours." |

| Gyula Krúdy, The Adventures of Sindbad |

| "The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there." |

| Leslie Poles Hartley |

In life, there are some films you'd like to see, some you want to see, and others a category all of their own: those that you simply need to see. Zoltán Huszárik's Szindbád/Sindbad* is one of these rare breed cinematic gems; one so bright, brilliant, and unique, that it will change the way you think about cinema as an art and as a mode of expression. Hyperbole, you might think – after all, I've been quick to judge the use of such language in the past – born from writing when still in the thrall of the gem's sparkle. However, for once, such words are entirely justified.

Widely regarded as a lost masterpiece, Szindbád is based upon the collected short stories of surrealist writer, Gyula Krúdy, who co-opted the popular Sinbad tales originating in Middle Eastern literature for his own. In his hands, Sindbad (played by famed Hungarian actor Zoltán Latinovits), is transformed from a seafaring adventurer who sails uncharted waters, encountering monstrous creatures and mythic beasts along the way, into a charismatic, dapper gentleman who encounters mysterious beauties and leaves a trail of broken hearts in his wake, as he tries to interpret the hardest map of all: the human condition.

Made following the success of Huszárik's breakthrough short Elégia/Elegy (his first professional film, produced by the famed Béla Balász Studio), his debut feature-length film carries with it a weighty reputation. Following its premiere in 1971, it was well received domestically, proving to be both a critical and commercial success. Over the years, its reputation grew. Hailed as one of the three best Hungarian films of all time in a 1985 poll (the top two spots were taken by Miklós Jancsó's Szegénylegények/The Round-Up and Károly Makk's Szerelem/Love), it maintained a similar standing some 15 years later in a poll to find the 'Budapest 12.' Beyond the realm of criticism, proof of its enduring popularity with Hungarian audiences was reaffirmed in 2010, when it topped an Index magazine poll (interestingly, four of the ten films listed also starred Zoltán Latinovits; testament to the late actor's popularity in his own right as much as the film itself). Beyond Hungary, however, the film fared less well. Though many critics were quick to notice its artistic merit during its low-profile release, they were mainly concerned with how audiences would receive and interpret the film, reinforcing the long-held Hungarian opinion that Krúdy's work was untranslatable and therefore unexportable.

Such is the nature of Krúdy's work that it's difficult to try and pin down exactly what kind of film Szindbád is. His highly detailed writings are lead by emotional rather than narrative logic; where the concept of time is elastic, rendering both conventional adaptation techniques and conventional film language, entirely useless. Huszárik and his co-writer János Tóth (Huszárik's cinematographer on Elegy, Capriccio/Whim and Amerigo Tot) went through several drafts (including one that ran to over 300 pages) before Huszárik settled on the idea of creating the film around the recollections of a dying Sindbad. Their final draft echoed the reverie trope that Krúdy often employed in his writing.

Once the structure, such as it is, was set in place, the only challenge – and arguably the biggest of all – left to Huszárik was to find a cinematic language that effectively mimicked the fragmented, poetic nature of Krúdy's prose. It's here where the true beauty of Szindbád shows itself. Together, the talents of Huszárik and his cinematographer Sándor Sára (who was already garnering praise for his work with Huszárik on Grotszk/Grotesque and other directors including Ferenc Kosa and Istvan Gaál), create a film that is stunning to look at in the pictorial and painterly sense, but their images also pack a great deal of emotional punch that transcends the boundaries of traditional spoken language. Just as Krúdy's work is writing of a different kind, Huszárik's is cinema of a different kind.

It's a perfect match.

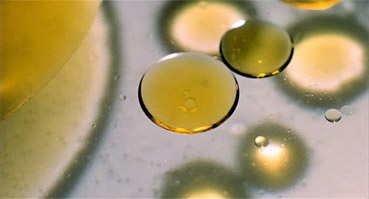

The rules of filmmaking and storytelling have been bent so far out of shape in order to film Krúdy's controversial and supposedly unfilmable work, that Huszárik casts them aside. Those expecting the sombre, austere style of his fellow countryman Béla Tarr, will be disappointed, but not for long. The opening moments of Szindbád are an assault on the senses. Colour, shape and texture collide in montage cut so rapidly that you barely have time to register something before you're seeing something else; and the use of flash-cuts throws you even further off course. I'd argue that even the most jaded of cinephiles, who believe they've seen everything and that there's nothing left to impress them, will be more than momentarily slack-jawed as they try to process it all. We see everything from blooms opening and oil on water, to vintage photographs and rain pouring off the weathered tiles of a roof – often in extreme close up using macro lenses, making them and their composition even more powerful.

The rest of what follows as an ailing Sindbad, teetering near death, journeys home, lying in the back of a horse cart without a driver to steer it, is just as sublime. The clock turns back, and we see glimpses of the young Sindbad in woodlands, transfixed by the two young ladies he's wooing as they dance together like fairies; then, follow him as he visits various different cafés and restaurants, catching the eyes of many more women. He's a restless soul, forever searching for something he can never quite find as he walks though winding streets and overgrown cemeteries. As the years pass, he grows evermore weary and reflective, musing upon his decisions, and selfish, hedonistic behaviour; always, somehow, finding his way home to his long-suffering second wife, Majmunka (Margit Dayka).

The seasons change before us, and Sindbad's past and present frequently collide, as he's reminded of people and places. There's a particularly poignant image of a red scarf being pulled from an icy lake that appears early in the film, which comes into play later when he skates with Fruzsina (played by Huszárik's wife, actress Anna Nagy), the woman he believes is his one true love. Few films have replicated memory and its workings as well as this, and it's not easy to call anything to mind that's comparable; with the exception of Alain Resnais' lament to lost love, Hiroshima mon amour/Hiroshima My Love, which it echoes in its use of flash-cuts and 'film as memory' narrative structure. Sometimes it feels as if the things we see are directly conjured from Sindbad's mind, as he occupies some half-state between living and dying; that we are seeing the "world beyond" he so often speaks of.

Therein lies both Szindbád's and Sindbad's charm. There's something intangible that draws you in about the film and the man both (Latinovits is a commanding presence, and it's easy to see why it's widely regarded as his defining performance in a distinguished career). There's always something to look at, to ponder and to consider. There are questions and ideas put forward about what everything might mean; and what you think is right one moment might not be the next. This is a film made for curious, hungry eyes, and it rewards its audience with many treats. It doesn't matter that there are some images you miss because they pass in a blink, or that others linger so we have a real chance to look at something. What matters is that we feel it and experience it. You'll quickly find that trying to piece together the narrative in terms of chronology and meaning is a futile pursuit and will distract you from immersing yourself completely in the experience of watching the film.

All of the beauty within Szindbád is tempered by sadness, and the entire film is suffused with a melancholy air. Death and the presence of it looms large from the moment we see Sindbad for the first time to the film's final moments when he leaves us behind with nothing more than a black screen, with all his memories in our own minds. Perhaps the saddest part of Szindbád's tale is that Huszárik himself is no longer with us. The passing of a director always lends their work a little more value. We mourn the person, and what they could have created, and so pay just a little more attention to all they've left behind. In the case of this director, clearly a man of great talent, thwarted by circumstance throughout his all too brief career, that sense of loss is greater still. And yet, there's something to celebrate, because thanks to DVD age, there's a second life unfolding for Huszárik and his work. Now, it can finally reach a wider audience and be appreciated in a way that eluded him during his lifetime.

It's the kind of immortality that Sindbad himself would crave.

We've come to expect the best possible transfers from Second Run DVDs, even when the source material is less than perfect, and Szindbád doesn't disappoint. There are still dust spots throughout, more so in some sequences than others, and the film grain is very visible at times, but the glorious richness of the colour, the sometimes sublimely judged contrast and the level of picture detail are al exceptional for a DVD transfer. This is a lovely looking film and the image here really does it justice. The framing is 1.85:1 and the picture is anamorphically enhanced.

The Dolby 2.0 mono track, which like the picture has been restored, may not have the range of a modern mainstream mix, but the dialogue is always clear (with a slight treble bias) and the music is bright with no trace of distortion. There is little trace of background hiss and no evidence of damage.

The clear English subtitles have been handled with care, moving to the top of screen when they would obscure important picture information in their usual position.

Though relatively easy to find in Zoltán Huszárik's native Hungary, Szindbád has been previously unavailable in the English-speaking world, until now. If that, plus the added caveat of restored picture and sound aren't quite enough for you, then read on, because there's even more to entice you into buying.

The quality of this release, like every other on Second Run's slate, is at an enviable level, right down to having one of the most beautifully designed covers I've seen. Beyond the mere fact that their work means you get to a cinematic treat such as Szindbád at all, if there's ever been a film crying out for such lavish attention, it's this one.

Szindbád: An Appreciation (12:18)

Filmed with the director of Katalin Varga, Peter Strickland, this a great watch, not least because of the knowledge and enthusiasm he brings to discussing the film, Huszárik, and the writings of Gyula Krúdy (which he's also familiar with). From the get go, it's obvious how highly Strickland regards Huszárik, his talent, his contribution to cinema history.

I'm a great fan of supplements like these, because it's always interesting to me to learn how people came across films, and how they've affected their lives. In the case of Peter Strickland, it's clear that Huszárik and Szindbád have left an indelible mark. If this doesn't want to make you watch the film, nothing will.

Booklet

Beautifully illustrated with stills from the film, this booklet is dedicated entirely to an essay on Szindbád, by Michael Brooke. Writing what, for the majority of readers, will be an introduction to the work of Huszárik and Krúdy both; Brooke's task not an easy one. Highly detailed, with references for further viewing and reading to boot, you'll come away from this not only knowing more about both these men in a factual sense, but the scope of the piece is such that you'll be making connections between them too, allowing you to appreciate and understand their work on an entirely different level. A fascinating and rewarding read, that's a fine compliment to the film itself.

Note: Second Run originally wanted to include Huszárik's famed short Elégia/Elegy, but were unable to do so due to last-minute issues with rights clearance. For those interested, you can view it here (many thanks to Michael Brooke for the information).

Szindbád is a truly breathtaking film, that's beautiful to look at, with a poetic structure, and a haunting, melancholy tone. It'll remind you why you love cinema, and show what it can achieve when its language is used by such skilled hands. An essential purchase.

* In George Szirtes' translations of Gyula Krúdy's work, Sinbad is rendered as 'Sindbad,' a convention followed in this review. |