"A desperate disease requires a dangerous remedy." |

Guy Fawkes |

It's interesting the way that the underlying concerns of a society are often dependent on the perceived prevailing international threat. When I was growing up, the fear of nuclear war was one that had the power to both terrify the general populace and galvanise the concerned into active protest. The weapons are still out there, sitting in their silos awaiting the wrong button push, but now the focus is on smaller scale devices, ones that could be strapped to the extremist charged with the job of delivering it. And so nuclear weapons don't keep us awake at night any more. But give it time. With terrorist activity of late largely confined to the Middle East, we're being encouraged to regard the likes of Iran and North Korea as the next big threat to world safety precisely because they are both, we are assured, developing a nuclear capability of their own.

It's probably fair to say that nuclear paranoia peaked in the 1960s, when the space race fuelled American fears of a Soviet threat from above, the Cuban missile crisis awoke the public to the possibility of genuine nuclear confrontation, and the increasing tensions and proliferation of nuclear weapons in both East and West made the prospect pf an apocalyptic third world war seem increasingly likely. It never happened, of course, but looking back it seems as much down to good fortune as it does to the caution of world leaders. It served to keep us all a little bit scared, but maybe that was the point. As Jim McDermott memorably reminded us in Michael Moore's Fahrenheit 9/11, you can make people do anything when they're afraid.

The first thing to note about Seven Days to Noon, an impeccably executed British thriller that trades most effectively on nuclear fear, is that it was made back in 1950, just five years after the first atom bombs were dropped and a good half-decade or so before that fear had spread far enough to fuel a more coordinated Hollywood response. The film's unsensational and workmanlike approach no doubt added to its realism back in 1950, but has also guaranteed that it has stood the test of time well enough to remain chillingly effective to this day.

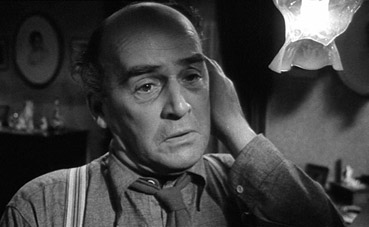

It all begins in typically low key British fashion. A letter lands on a doormat and comes to the attention of CID superintendent Folland (André Morell). We know little about its contents at this stage, but they're extreme enough to prompt Folland's colleague to dismiss it as the work of a crank. Folland is not so sure, and a phone call to the sender's workplace alarms him enough to drive straight up there and confirm what he has just heard. It quickly transpires that Professor Willingdon (a quietly superb Barry Jones), a key research scientist at a government nuclear research centre, has become disillusioned with his work and has decided to take steps to stop it. To that end, he has stolen a small nuclear device and promised that if all British nuclear development is not brought to a halt he will use it to destroy the seat of government at noon the following Sunday, taking out a large area of London in the process. Aided by Willingson's daughter Ann (Sheila Manahan) and his long-time assistant Stephen Lane (Hugh Cross), Folland has just seven days to locate Willingdon and disarm the bomb.

It's a terrific set-up that proves the perfect material for John and Roy Boulting to follow up their 1947 masterpiece Brighton Rock. Initially staying with the investigation and allowing Willingdon to remain a ghostly threat, his introduction on day two (days of the week act as an effective countdown) neatly shatters any demented scientist preconceptions. Willingdon is no leering villain, but a quietly spoken middle-aged man of ordinary appearance and polite demeanour, sympathetic and well rounded enough to allow the Boultings to play games with audience allegiance, as we find ourselves perversely rooting for both Folland's investigation and Willingdon's efforts to evade capture.

The background and setting soon prove as interesting as the activities of the main characters, as preparations are made for evacuation and public speculation about an approaching war turns to frustration, fear and dissent. The dense texturing and attention to detail is such that even the smallest speaking role is given a specific personality and distinctive dialogue – the spiv trying to sell a room near Brighton and the two soldiers complaining about their 'flipping' orders are memorable examples from many, despite being on screen for just 10 and 12 seconds apiece. Particularly impressive is the handling of the evacuation itself, the combination of stock footage and staged action creating a most convincing picture of a coordinated city-wide operation (which of course is carried out in an orderly fashion without a hint of panic – we are British, after all), the subsequent empty city streets as spookily unsettling as anything in The Day the Earth Caught Fire or 28 Days Later, which shares with this film a key bridge location for its deserted London sequence.

Tension is built through the viewpoint-switching cat-and-mouse structure and the knowledge that a happy conclusion is by no means guaranteed in a film in which lessons are being delivered alongside the entertainment. The threat is personalised when the hunted Willingdon re-visits a faded actress he has befriended and holds her prisoner in her own flat. By then, his soft-spoken conviction has taken on a more threatening air, like that of Richard Attenborough's John Christie in 10 Rillington Place, while the suggestive links made between his religious convictions and his decision to become a suicide bomber give the film an unsettling contemporary resonance.

The defiant prime ministerial speech may suggest that the film favours the nuclear deterrent argument, but a voice is also given to public dismay at the terrors that science has unleashed, and Willingdon's horror at one man's suggestion that we should adopt a first strike strategy is one that's easy to share – "You don't understand what you're saying," he tells the man, "can't you see that what you're suggesting would mean the total destruction of mankind?" That the man reacts with a dismissive "Ah, that's what they said about the last one" is made all the more troubling by the number of times I've heard that very response to a similarly made point.

Strikingly lit and shot by second time out cinematographer Gilbert Taylor (who went on to build a seriously impressive CV that includes Dr. Strangelove, A Hard Day's Night, Repulsion, Cul-de-Sac, Frenzy, The Omen and Star Wars), scored with subtlety by John Addison, and earnestly performed by the entire cast (with a few justifiable exceptions for the comic asides), Seven Days to Noon is a damned fine example of the Boulting Brothers at their cinematic storytelling peak, and a cracking, socially relevant thriller to boot.

A 1.66:1 anamorphic transfer whose comfortable framing suggests this is the correct aspect ratio, struck from a cleaned up but not quite perfect print whose dust spots are busier on the stock footage, suggesting they may actually be part of the print of the film. Sharpness is good, however, and the contrast very impressive, with rock solid black levels really contributing to the night-time street scenes,

The Dolby 2.0 mono soundtrack has an underlying hiss that is more audible in quieter scenes but which I completely forgot about as I got involved in the film. The dialogue displays the dynamic range restrictions you'd expect from a work of this vintage, but is otherwise fine.

Not a bean. A real shame actually, as some background information on how some of the grander scenes were staged (or faked) would have been welcome.

An excellent nuclear thriller that really benefits from its low key approach and deserves to find the cult audience that have already taken the aforementioned The Day the Earth Caught Fire to its heart. An extras-free disc from Optimum, but the transfer is a good one and the film still comes heartily recommended.

|