|

Possibly

the most striking and unexpected image in Nuru Bilge Ceylan's

quietly mesmerising 2002 film Uzak was the

sight of Istanbul buried under a carpet of snow. It's not

that it never snows in Istanbul, but that we so rarely see it

shown that way on film. Istanbul is almost always portayed as a scorching hot location, and to see if covered in the

white stuff was, for me at least, an eye-bulging moment.

With It's Winter [Zemestan],

Iranian director Raffi Pitts provides us with a similarly

wintry view of Tehran, another city that has largely escaped

such cinematic presentation in the past. At least

you're a little more prepared here by the title and the

poster, which features a heavily coated figure running through a bright white and only sparesely featured snowscape.

There

are those who go into depression during the winter

months, who whither when deprived of the summer sunshine

and heat. I am not one of them. Quite the opposite. For

me, summer is too bright and too damned hot.* I like the

winter, but snow is something I now see on TV or in

films or read about rather than experience. I miss it. But I appreciate

the potential of bleak, snowy winters as a metaphor

for isolation and unhappiness (memorably realised in Dagur

Kári's 2003 Nói albinoi),

the landscape reduced to a single colour, its inhabitants

cocooned against the cold in heavy clothing that strips

them of their individuality. Insufferably upbeat Christmas

stories aside, snow is rarely one of cinema's good omens.

This

is certainly the case in the evocative opening scene of

It's Winter, where a man's dejected face

and posture, the closing of a workshop, a close-up of a

padlock being secured and a slow, unhappy walk through a

snowstorm are all that is needed to tell us that the character

we are following, the unfortunate Mokhtar, has lost his

job and has little prospect of finding another. By the time he reaches

his isolated house he has come to a decision, to leave his

young daughter, his mother and his wife Khatoun, and go of in search

of work abroad, promising to return with money as soon

as he can.

As

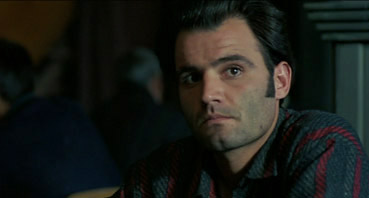

Mohktar leaves the district, enigmatic drifter Marhab arrives, landing at the local hostel too late for a meal but

still with enough energy to ingratiate himself with fellow

occupant Ali Reza, whom he persistently pesters into friendship.

Marhab is also looking for work and is initially undeterred

by the lack of opportunities here, harassing potential employers

like an Iranian Yosser Hughes and eventually landing engineering

work alongside his new friend. But the boss doesn't seem

to like him, his pay is not forthcoming, and Marhab would frankly

rather be off having fun. By this point he's caught sight

of Khatoun going about her daily business and has become

entranced by her, to the point where he will sit across the

railway tracks from her house just to watch where she lives.

When she is unable to afford a red sweater for her daughter

at a market, Marhab buys it and delivers it to her house,

offering it to the daughter but chased away by Khatoun's

morally protective mother. One day, with nothing heard from

Mohktar since his departure, the police arrive at Khatoun's

door with bad news, which Marhab observes from his watching

place across the tracks. Is now the time to approach Khatoun

and declare his interest?

But

what exactly is his interest in her? If the above gift-giving makes Marhab

sound like a sensitive gentleman, then I've perhaps been

sugar coating him just a little. He's interesting, sure,

but not instantly likeable, coming across as pushy, boastful

and a little shifty, and for a while it's uncertain

that his intentions towards Khatoun are in any way honourable.

But increasingly, there's the sense that the man really is

captivated by this woman's quiet elegance and beauty (and

as played by one of Iran's top female stars Mitra Hajjar,

she certainly displays both), and that there is more than

just lust involved here. This is heightened in their first

awkward meeting, when Khatoun confronts Marhab and demands

to know why he has been following her, prompting the sort

of fumbled, embarrassed response you'd expect more from a shy

teenager than a seemingly self-assured man in his thirties.

Marhab's

subsequent increase in confidence and more determined pursuit

of Khatoun's attention could probably have filled half-an-hour

of screen time, but is dealt with here in less than a minute's worth of

carefully chosen shots. This stylistic

economy allows Pitts to develop the story briskly without

ever hurrying the pace, his focus on character balanced

by a critical view of the employment prospects and financial

hardships in this particular quarter of Iranian society.

There's a captivating sequence towards the film's end when

Marhab bemoans his situation to the proprietor of a bar

in which he is resting, but the camera is angled in such

a way that he appears almost to be directly addressing the

audience. "What's the point?" he asks us, "To

know a trade and be unemployed. What's the point?"

It's a pertinent question and one that transcends national

boundaries – at this moment he could be sitting in the

run-down industrial quarter of just about any number of

cities.

For

both Mokhtar and Marhab, an inability to find work acts

as a form of emasculation, excluding them from one of the

very things that defines their role in both society and

their own family (that Khatoun remains in work throughout

the story no doubt adds to their feelings of dejection).

Marhab may prefer to have a good time rather than work,

but this is hardly the point – he wants to be in a position

to choose, not to have it forced on him by circumstance.

It's an issue whose cinematic lineage goes back to depression-era

America and even silent cinema, and was memorably captured

on British TV in 1982 by Alan Bleasdale's Boys From

the Blackstuff. The unchanging nature of the problem

is underlined here by the sense that history seems destined

to repeat itself, though is also reflective of the cyclic

nature of much of Iranian cinematic storytelling. But Pitts

is wise to this sense of the inevitable, and nicely upsets

expectations with a particularly poignant late-story sting.

It's Winter

has been repeatedly described as bleak, but this fails to

acknowledge its visual poetry (Mohammad Davudi's cinematography

is consistently excellent), its arresting location work

and sense of place, its dramatic and thematic depth, its

brief but memorable upbeat moments, and the hold it can exert

over the willing viewer. There's an honesty to both the

drama and the social commentary that springs in no small

part from the naturalistic performances from a primarily

non-professional cast – Marhab's speech about his poor employment

prospects doubtless comes from the heart, given that the

man who plays him, Ali Nicksaulat, is not an actor by trade

but an engineer who works in the very district in which

the film is set. It's an absorbing and haunting film that

cares about its characters and their fate, and while

specifically Iranian in identity, speaks clearly to a far

wider audience.

An

excellent 1.85:1 anamorphic transfer really does justice

to Davudi's cinematography, with contrast and detail both

of a very high order, perfect black levels but good shadow

detail and naturalistic colours – when they need to be brighter,

as in the factory that Marhab invades in search of work,

they shine.

The

soundtrack is Dolby 2.0 stereo only, but the clarity and

separation are both first rate and add to the film's strong

sense of place, particularly in the exterior locations –

you can even hear the snow as it lands. A really good job

all round.

Interview

with Director Rafi Pitts (40:19)

Even if you've done your research and know that Rafi Pitts

was born in Tehran but fled during the Iran-Iraq war and

studied film at the Polytechnic of Central London, you're

still likely to be surprised at just how English his accent

is. Right from the start, this is enthralling and informative

stuff, as Pitts discusses neo-realism, poetry, the preparations

for the film, the intention to make a work that the community

in which it is set would go to see, and a whole lot more.

The story of how he got non-actor Ali Nicksaulat to look

so embarrassed when confronted by Khatoun is particularly

enjoyable. In

the absence of a commentary, this will do very nicely.

There's

also a brief Biography of Rafi

Pitts.

A engrossing blend of personal drama and social commentary

whose downbeat tone feels appropriate for its setting and

story, and it's so well handled that although a sobering experience,

it's not a depressing one. It's well presented on Artificial

Eye's DVD, with a first class transfer and an enthralling

interview with its director. Recommended, unless your viewing

consists solely of upbeat Hollywood actioners, and then

the chance is you didn't make it to this part of the review

anyway.

|