|

Imagine a society that employs human sacrifice for what it believes is the common good. Go back far enough and you'll find quite a few. Bronze Age Incas ceremonially disposed of its citizens at banquets and royal funerals, the Aztecs killed people in their thousands to appease their sun god Huitzilopochtli, and in ancient China, the unfortunate were ritually executed to keep the river god Hebo happy. But this is all in the distant past, a time when humanity was so in fear of deities of its own creation that it was willing to murder its own kind to appease them. It's the very idea that such barbaric ignorance could still exist in a more enlightened age that made (and continues to make) the climax of The Wicker Man so disturbing. So imagine a modern industrial society that embarks on a programme of random sacrifice for what it believes is the good of society at large. Such is the premise at the core of Takimoto Tomoyuki's gripping social drama Ikigami, adapted from Mase Motorō's best-selling manga and retitled Death Notice: Ikigami for its UK release.*

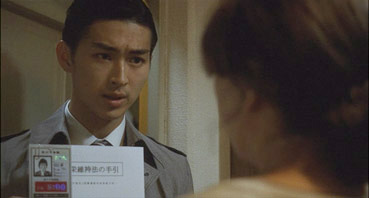

In a near-future Japan, the government has passed the Prosperity Act, a law that requires every child in the country to be inoculated against disease with a serum that will kill one in every thousand of them between the age of 18 and 24. The measure is designed to stem the country's downward spiral and, in the words of those responsible for the Act, "heighten awareness of the value of life and provoke civic mindedness, morality and the desire to be a productive citizen." The deaths are caused by nano-capsules designed to explode at a date and time known only to the officials at the so-named Ministry of Health and Welfare, who employ a small army of officers to deliver an official death notification – the Ikigami of the title – to the doomed individuals twenty-four hours before their allotted time of expiration to give them a day to put their affairs in order. Part of a new intake of young officials is Kengo Fujimoto (Matsuda Shota), who despite landing what is regarded as a prestigious position, is clearly troubled by the morality of his new profession. He's not the only one. During the induction talk given by ministry boss Morio (Emoto Akira), a fellow inductee who lost his girlfriend to the Prosperity Act angrily denounces the law, and is quickly sedated and dragged from the room. As Fujimoto is later reminded by stony-faced section head Iishi (Sasano Takashi), openly questioning the Act is illegal, and anyone who does so faces prosecution for thought crimes, for which they can be imprisoned and psychologically reprogrammed.

Far-fetched though this may sound, as presented here it feels chillingly plausible, unfolding in the manner of a dystopian social drama, one whose early scenes in the Ministry owe more to the impersonal sterility of Gattaca than the faux-futuristic décor of regular science fiction cinema. There's a cultural element at play here, of course, with the rows of dark-suited bureaucrats less a representation of autocratic suppression of individuality than an extension of the country's rigidly conformist salaryman culture. Initially there's a suspicion that the story will develop along the lines of a more low-key Logan's Run. In both films, citizens are executed for the supposed good of society, and both centre on a male operative who questions the morality of the law he is charged with enforcing. But where Logan's Run develops into a science fiction thriller, Ikigami takes a very different tack, and just fifteen minutes in it pulls off a most effective and unexpected switch of perspective.

From the moment Fujimoto opens his first assignment, you're struck by the appalling nature of his job, one that requires him to tell 23-year-old aspiring musician Tanabe (Kanai Yuta) – whose cheery file photo could be that of any young and hopeful college student – that in twenty-four hours he will die for the good of society at large. Yet although clearly ready and rehearsed for the task ahead, when Fujimoto arrives at the designated address, he encounters not Tanabe but his widowed mother, who pleads desperately with him to spare her only child, a boy on whom she dotes and relies.

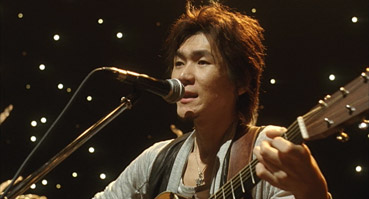

By this point the film has established Fujimoto as its central character and the expectation is thus that, after his encounter with Tanabe's mother, we will follow him home and watch him wrestle with the morality of his new occupation. But instead the focus switches to the doomed Tanabe, who arrives home late from the recording studio to be confronted by the news of his upcoming death, and Fujimoto is sidelined to allow the film to confront the very human consequences of the ikigami he has delivered. And they are, without a whisper of exaggeration, emotionally devastating. Tanabe is a musician on the brink of his big break who began his musical career busking with his best friend Hidekazu (Tsukamoto Takashi), a talented songwriter whom he abandoned when he was talent-spotted for his role in the company-manufactured musical duo T-Birds, where he has become little more than a backing musician for egocentric front man Tatsuhiko. Just how much to reveal here is a difficult call, but it's worth knowing up front that the effects of the nano-capsule cannot be reversed and that Tanabe's fate is essentially sealed. It's not about whether he lives or dies but how he deals with the limited time that remains. And herein lies the film's emotional power. While some of what follows plays out as expected, a good deal does not, and it builds to a climax so emotionally overpowering that it had even this cynical old fool wiping tears from his cheek.

At which point we're only halfway through the film.

Ministry operatives are forbidden to interfere with the lives of the victims, but his next two assignments present the increasingly troubled Fujimoto with twin dilemmas that make it impossible for him to remain on the sidelines. The first irony-riddled encounter sees him intervene to prevent depressed recluse Naoki (Sano Kazuma) from killing himself, only to then hand him the notification of his impending death (laughing in almost hysterical disbelief, Kazuko asks Fujimoto, "Have you come here to save me or kill me?"). It doesn't end there. Naoki, it turns out, is the son of Takazawa Kazuka (Fubuki Jun), a former thought criminal turned conservative politician who now vigorously campaigns for the merits of the Prosperity Act. So convinced is she of her conditioned beliefs that instead of recoiling in horror at her son's impending death, she makes it part of her campaign, presenting herself as a mother who openly supports her own son's willingness to give up his life for the good of the state.

It's with his third case that Fujimoto consciously crosses the forbidden line, when his lack of awareness jeopardises the attempts of the previously carefree Satoshi (Yamada Takayuki) to keep the news of his ikigami from his blind sister Sakura (Narumi Riko), to whom he is planning to secretly donate his corneas after his death. With Sakura refusing the operation and threatening to take her own life if what she overhead was true, it's Fujimoto who comes up with a plan to convince her otherwise, one inspired by the manner in which Naoki's story concludes and that will require the cooperation of every worker and patient in the hospital in which the operation will take place. Here the two stories run side-by-side and once again run the risk of dissolving into cliché, but are so well developed, so intelligently handled and so earnestly performed that they prove every bit as involving as their emotionally charged predecessor.

Although the three stories highlight the human cost of the enforcement of the Act, the film boldly plays devil's advocate by suggesting that the measures are actually having the desired effect, that the economy has stabilised and that crime and the previously high suicide rate have been drastically reduced. It's a similar story with the condemned individuals – with only hours to live, they confront their past mistakes, attempt to repair broken relationships and adopt a selfless and caring attitude to those they have previously taken for granted. This is memorably brought home when Fujimoto questions the role of his department following Tanabe's heartfelt final performance. "He was truly alive for the first time when he sang that song," Iishi tells him. "What made the song shine was your ikigami."

Taken literally, the Prosperity Act may seem as unlikely as the Millennium Act in Battle Royale, which attempted to combat rising teenage violence and disrespect for authority by randomly selecting a class of school-children and forcing them to fight each other to the death. But like that of its notorious cousin, the morally extreme law that is central to Ikigami makes perfect sense when viewed allegorically. You don't have to look far for the reference points, as those currently being put out of work by our own men in power in the name of economic growth will doubtless testify. Here, a real-world Prosperity Act ensures that a sizeable portion of the populace are financially sacrificed for the theoretical good of the society at large, a society that, like its Ikigami equivalent, is encouraged to focus on optimistically fashioned statistics regarding the economic effects and ignore the human suffering that results.

From this perspective, it's only right that the film ultimately sides with the victims of the Act and makes it clear that in a supposedly civilised society, the end really cannot justify the means. Good deeds result from the victims being forced to confront their mortality – one of which proves genuinely life-transforming (a sequence whose astonishing emotional kick prompted my second flurry of tears) – but they fail to justify the cold inhumanity of a process that destroys not just those marked for death, but their families, their friends and even their work colleagues as well. And despite safeguards to ensure the cooperation of the victims, the process can, like its real-life equivalent, backfire on the society it is designed to benefit, when those with nothing to lose use their brief remaining time to settle old scores and dish out their own specifically targeted ikigamis.

Dark though its central concept may be, Ikigami is first an foremost a humanitarian work, one that focuses our attention, like those of the Prosperity Act victims, on the value of life and the importance of even its most everyday elements. The sense that those in power remain blinded to the true consequences of the Act they administer is brought chillingly home in the final few minutes, as a new batch of six-year-olds are led cheerily indoors for an inoculation that will, in a few years time, bring some of their lives to a premature end. It's all the more disturbing that their progress is encouraged by medical staff who include in their ranks a former protestor who has since been reconditioned to enforce an Act he once vehemently opposed.

But in a pair of brief and immaculately timed late scenes, we are left with a glimmer of hope that change could be on the way, in the inspiring determination of one man to fight the system from within in the name of his late son, and in whispered advice to Fujimoto from an unexpected source that suggests dissent is more widespread than he or we realised, and that it may even be organising for positive action. Like so much in this criminally unsung but compellingly made and emotionally charged film, these understated but beautifully judged moments remind us that when faced with death, the thing we sometimes learn most is the true value of life.

As with many MVM releases, the 1.85:1 anamorphic transfer here has been standards converted from NTSC to PAL. The result is a mixed bag, with a good level of detail tempered a little by sometimes visible jaggies and a slight roughness to some edges that may or may not be a side-effect of picture enhancement. The colour palette is muted and the brightness toned down, but whether the dominant earthy hue is a conversion issue or was a deliberate artistic choice is a hard one to call. The contrast range is good, though the black levels are just off in darker scenes and sometimes suck in some of the surrounding detail. Not perfect by any means, but still very watchable.

The Japanese Dolby stereo 2.0 track is bright but appropriately low key, livening up for Tanabe's musical performances and those occasional moments where the score gets to work on our emotions. The English subtitles are optional.

Trailers (2:07)

Two smartly cut Japanese trailers – the first and longest has English subtitles and misleadingly sells the film as a fast-paced thriller, while the second is subtitle-free and is considerably more ambiguous about the film's style and content, but still acts as a neat hook.

I'm well aware that I've missed the release date on Death Notice: Ikigami by a good few weeks, but decided to go ahead with the review nonetheless, largely out of concern that the film appears to be slipping under the radar of the audience who would appreciate it most. The lack of a UK cinema release and international festival attention, coupled with the similarity of its English title to the Death Note cult anime series, could well result in it being unfairly overlooked. Although it repeatedly risks tipping over into sentimentality, Tomoyuki's consistently thoughtful handling and the sincere and understated performances make its heartfelt humanism disarmingly easy to respond to. The lack of extra features on the DVD is a bit of a shame (I, for one, would love to know more about the director, his talented cast and the production in general) and the standards converted transfer is serviceable rather than exceptional. But for the film alone, which is as intelligent and emotionally affecting as anything I've seen in the past couple of years, the disc still has to come warmly recommended.

* Japanese word 'ikigami' apparently refers to someone who carries out the actions of a god, a culturally appropriate description of those charged with enforcing the Prosperity Act.

|