| |

"If it wasn't for the people, it was very pretty. The people over there are very backward and primitive and they just make a mess of everything." |

| |

Lt. George Coker, asked by schoolchildren to describe Vietnam |

| |

|

| |

"The Oriental doesn't put the same high price on life as does the Westerner. Life is plentiful, life is cheap in the Orient." |

| |

General William Westmoreland. |

And these are just two extraordinary quotes from many – this is a film loaded with memorable,

sometimes prophetic and occasionally outrageous lines. The trick is, of course,

that none of them are scripted, but real opinions straight

from the mouths of willing participants. I'll bet real money

that with the release of the film and the passing of time,

a few of them were given cause to look back and wince at

their own words. Or at least I hope they would. But we live,

once again, in interesting times.

With the documentary feature, and especially the political

documentary feature, having recently enjoyed a popularity

boom of late, the timing seems perfect for a cinema re-release (last

year in the US) and DVD release of Peter Davis's extraordinary,

ground-breaking film from 1974 examining the damaging effects

of the Vietnam war on the American people. One of the only

films about the conflict that was made and released before

its conclusion, it has found renewed political relevance

in post-Iraq war America, where 1960s fear of communism has been traded in for 21st century terrorist paranoia,

prompting similarly polarised public and political attitudes

and quotes as dogmatic, ill-informed and simplistic as any

you'll find here.

But

despite Hearts & Minds' strongly political

standpoint, it never for a moment becomes a simplistic polemic.

The above quoted remark from Lt. George Coker, for instance,

delivered as a response to a question from a class of young

and attentive students from his old school, may seem damning

in isolation. But Cukor had recently returned home after

seven years as a prisoner of war and appears trapped in

a dreamily patriotic early-1960s time warp, even at one

point talking of how America won the Vietnam war, seemingly unaware

of what is happening around him. It's a similar story with the Emerson

family, who talk about the loss of their son in combat – they are at all times treated with respect, with their son's decision to go to

war never questioned or criticised, and only the father's devotion

to the policies of the soon-to-be-disgraced Richard Nixon

even hinting at a degree of patriotic naiveté on their part.

It's intriguing that Davis chose only to interview people who were or had been in favour

of the war, which means that all of those

presenting a critical viewpoint do so with the hindsight

of personal experience. The technique is a persuasive and effective

one: a native American talks of the absurdity of wanting

to "go out and kill some gooks" after being the

butt of extensive racism himself; an ex-pilot discusses

the dropping of bombs and napalm as a technical exercise

until he reflects on how he would he would feel if it were his own children being killed; a former marine talks about

his conflict-inspired bloodlust, only for us later to realise

that the war has left him paralysed from the waist down. Probably the

most instantly engaging interviewee is young William Marshall,

whose passion and street-talk delivery make him a most persuasive

voice of protest, though his gripe is less with the war

than the treatment of the returning soldiers. The real coups,

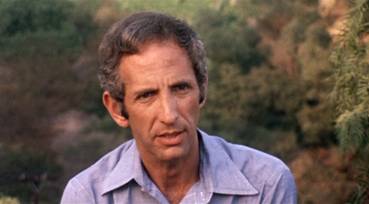

though, have to be the disillusioned representatives of

officialdom, of whom former Defence Aide Daniel Ellsberg

delivers perhaps the film's most potent and famous quote:

"We weren't on the wrong side, we are the wrong side."

There

is no voiceover and only a minimal use of informative captions,

but Davis delivers political body-blows through his sometimes

brilliant use of editing and juxtaposition, repeatedly presenting

what appears to be an even-handed view that is then subverted

by the footage or interview that follows it. Thus an attempt

to explain the inevitable thrill of carrying out a bombing

raid, where the pilots are distanced from their victims

and the air force technology is openly celebrated, cuts

to shots of Vietnamese peasant farmers working with the

most primitive of tools, very graphically emphasising the

technological gulf that lies between the natives and the

invading force. Elsewhere, a shot of a Zippo lighter in a

brothel, in which two American servicemen are availing themselves of the

local girls in a scene that is startling in its frankness, resonates

a few minutes later when what might as well be the same

Zippo is used to set fire to the house of a Vietnamese family,

who stand mournfully by as their lives and their home are

destroyed with no more effort or concern than it would take

to light a cigarette. Occasionally, it is the very absence

of editing where normally you would expect to see it –

most notably on the shot of elderly Vietnamese sisters,

one of whom has lost both her other sister and her home

to American bombing, that holds long after the interview

has finished – that proves most affecting, reflecting Davis's

desire to focus precisely on the aspects that normal news

broadcasts quickly pass over, the so-called 'dead air'.

Perhaps

the most striking aspect of the film is how contemporary it feels,

its use of editing, music, historical and even movie footage

providing a clear lineage to the work of modern political

documentarians like Michael Moore, who regards

Hearts & Minds as possibly the finest

documentary he's seen and has more than once cited it

as the film that inspired him to become a documentary filmmaker.

This very fact will no doubt prompt the usual "If only

Michael Moore would [insert critical bollocks here]"

moans from the one-note naysayers, but Davis himself appears

thrilled that a new generation of political documentary

feature makers have taken up the torch. The parallels to

Moore extend to this film's Academy Award win for Best Documentary,

an event that went down in Academy history (as did Moore's

notorious win) following producer Bert Schneider's reading

of a telegram of friendship from the new Vietnamese government.

This so outraged hosts Frank Sinatra and Bob Hope that they

then made their own, hastily cobbled together speech of

apology and allegiance, only to have Shirley MacLaine walk

on and offer her support for Davis and his film. After the

ceremony, Francis Coppola also spoke in the film's defence

and later told Davis that he had watched Hearts

& Minds "a couple of dozen times"

in preparation for Apocalypse Now, a film

Davis himself is a huge fan of. Davis

himself is disarmingly modest about his very considerable

achievement, but 30 years on Hearts & Minds

remains a powerful, persuasive and unsettling experience,

and still casts an awesome shadow over the present wave

of political documentary works.

Well

here's a thing. Knowing that the film was already available

in the US as part of the esteemed Criterion Collection,

I couldn't help wondering how this region 2 disk from Metrodome

would shape up by comparison. Not that I have the Criterion

disk, mind you. Well I have now, as such. Place the Metrodome

disk in your drive, select 'play film' and the first thing

you are presented with are the familiar Criterion Collection

and Janus Films logos, which surprised the hell out of me

I can tell you. From this I can presume that the transfer

has been officially licensed from Criterion and is thus

of similar quality, NTSC to PAL conversion notwithstanding

(and this does create a few minor issues). As you might

expect from such a pedigree, this makes for largely pleasing

picture quality, especially given the various source materials

used, from news footage to movie extracts to archive film

and photos. The slight softness and film grain on some of

the source material is never distracting, contrast is fine,

and the picture is largely clean of dust and damage. On

the whole, a very nice job. The framing is 1.85:1, within a small black border which

enlarges over the opening and closing credits. The picture

is anamorphically enhanced.

Sound

is Dolby 2.0 stereo and is clear and free of noise, with

separation confined largely to the music score.

The

Interview with Peter Davis (21:55)

is non-anamorphic 16:9 and suffers from very fluffy sound,

but the content is useful, putting a face to the man and

providing information on his arrival to the project by way

of his earlier CBS documentary, The Selling of the

Pentagon, his first major flirt with controversy.

Davis outlines his approach to the film and its structure,

and draws direct parallels between the conflict in Vietnam

and recent US military action in Iraq. He also discusses

the recent appetite for non-fiction films and bemoans the

shallow nature of modern Hollywood dramatic cinema and the

deadening effects of CGI (hoorah!).

The

Commentary by Peter Davis is moderated

by Time Out critic Nick Bradshaw and largely screen-specific,

though some sequences do seem to have been spliced in from

elsewhere in the conversation. Despite a couple of dead

spots, this is thoroughly interesting stuff, providing longed-for

information on how some of the footage was shot (the brothel

scene in particular) and how much of the film was made up

of library and source footage (only about 10-12%). Davis

also provides a postscript on some of those interviewed,

one of whom has become an activist of some note on a variety

of issues. Particularly touching is the memory of the screening

held in Vietnam some time after the end of the war that

prompted one woman to say at the film's end "I hate

you all over again," before giving Davis an emotional

hug.

It's

interesting to read reactions to the film from a new generation

of reviewers who quite probably have never been involved

in active protest, some of whom have complained about the

film's openly political standpoint and lack of balance.

Which is, frankly, ludicrous. A word to the not so wise

– there is no such thing as a completely balanced documentary,

and it's just a matter of how clearly the film-maker expresses

his viewpoint. You are always being steered in

one direction or another. And even if complete balance were

possible, the very concept of a political documentary with

no political standpoint is oxymoronic. Hearts &

Minds makes its viewpoint clear and does so to

compelling effect.

If

you don't have the Criterion disk or a multiregion player

then this Metrodome release will do fine, especially as

it is sourced from the same transfer and has its own commentary

(Davis also provides a solo commentary on the Criterion

release). Either way, this is one of the most important

and affecting examples of political documentary in modern

cinema and is, as Michael Moore so rightly says, "required

viewing."

|