|

A shopper casually browsing the shelves of their local video

store who encountered the DVD of Frog Song would be forgiven for instantly classifying it as a surrealistic

oddity. The title offers precious little clues to the content,

the box blurb describes the film as "truly bizarre,"

and the cover picture shows a young woman walking hand-in-hand

down a city street with an adult-sized humanoid frog, suggesting

an amphibian love story twist on Spike Jonze's memorable

music video for Daft Punk's Da Funk. All of which

is thoroughly misleading and gives no indication of the

considerable qualities of what is actually a tender and

involving drama on the frailty of friendship.

Frog

Song is a literal translation of the Japanese re-release

title Kaeru no uta, and was originally released

as Enjo-kôsai monogatari: shitagaru onna-tachi,

which translates roughly as Friendship Support Story:

Women Who Want to Do. Not very poetic, but it does

give a clearer indication of the theme. Frog Song

is an example of modern pink cinema, and if this term is

new to you then you can find a brief summary in our review

of Mitsuru Meike's Bitter

Sweet. Like most works of this uniquely Japanese

sub-genre, Frog Song runs for just over

an hour and has the requisite number of evenly spaced sex

scenes. In common with many of the better genre works, they

are logically and effectively integrated into the surrounding

drama and allowed to run only slightly longer than the story

needs them to, while their eroticism arises from their air of realism rather than the music accompanied softcore silliness

of traditional western adult dramas.

The

links with the aforementioned Bitter Sweet extend beyond the casting of lead actress Konatsu. The narratives

of both films are fuelled by an increasing non-permanence

in Japanese relationships, with a more empowered female

population no longer willing to silently tolerate male infidelity.

This stance is graphically illustrated in the opening scene

when the young Akemi (Konatsu) angrily hits her boyfriend

over the head with a bottle and, muttering a quick apology,

walks out on him. She takes refuge in a manga café,

but when fellow customer Kyoko (Rinako Hirasawa) picks up

the book she had planned to read, she becomes disproportionately

upset, tearfully harassing the girl until the book is reluctantly

returned.

This

fraught encounter actually unites the mismatched pair with

an economy typical of modern Japanese cinema, established

in a single edit and conversational references to discussions

that we have not been witness to. Their friendship develops

in sometimes surprising ways. In another nicely executed

time-jump edit, we find an almost naked Kyoko on bed a receiving

the sexual attentions of an older salaryman while the clothed

Akemi uncertainly watches on. Only in the scene

that follows do we realise that Kyoto is working as a part-time prostitute

and that Akemi agreed to participate in an arranged threesome,

probably more out of curiosity rather than any desire to actually

be involved. The sexual experiences of the two women are

clearly very different, as are their relationships with

men – for the friendless and live-alone Kyoko, sex is just business,

while for Akemi it's part of a relationship that she can't

seem to completely break free from, despite catching her

boyfriend in bed with another woman the day after their

break-up (in a memorably oddball moment, the two women later

end up beating each other with French loaves).

A particularly intriguing aspect of Frog Song is that although it adheres to genre conventions regarding

the quantity and narrative spacing of the sex scenes,

sex itself is shown as having a largely negative effect

on the lives of both women. Its purely functional role for

Kyoko may or may not be responsible for her state of relative

isolation and later proves destructive to her health in

general, while the abuse she suffers at the hands of two

S&M aficionados is a favourite movie way of suggesting

that the time has come to get out of this business. Akemi,

meanwhile, doesn't get to sit on the sidelines for long

and is pressed by Kyoko into taking on a customer of her

own, a task she performs with enough struggling reluctance

to prompt her friend to rethink the wisdom of her decision.

Later, she attempts to follow through on a stalled dream

by agreeing to take a beating from a customer instead of

sex, a sequence that in a single punch strips this particular

form of S&M of even a hint of perverse glamour.

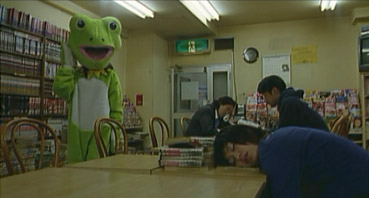

It's

the unpredictable and sometimes troubled development of

the friendship between the two women that provides the film

with its emotional heart. It hits an engaging peak when the

pair sing and dance like excited schoolgirls to the Frog

Song of the title, but increasingly finds itself on troubled

ground. Akemi is repeatedly pestered by her ex-boyfriend

to come home – something Kyoko takes a selfish step to prevent –

and finds temporary sexual fulfillment by imagining herself

in the sort of relationship she has never known. Akemi's

frog fascination, meanwhile, which presumably is the source of the above mentioned cover quote about the film being bizarre, is actually no different to that of any

young girl with a liking for a particular animal in fluffy

toy form, while the life sized frog suit she buys gives rise

to the film's most surreal but touchingly affecting sequence,

when it is worn by Kyoko as an apology to her friend. Their

eventual parting has real emotional sting – too late comes

the realisation of their depth of feeling for each other

and the relationship that might have been.

The

few-years-on coda – introduced in the best time-jump edit

in the film – initially seems unnecessary, but follows through

on the feminist leanings of earlier scenes to show us two sisters

who really are doing it for themselves (hence the original

Japanese title). It ends on an everybody-join-in musical

dance number that, despite smashing a hole in the film's

carefully constructed reality, has a stumbling, hastily

choreographed exuberance that just filled me with joy. It's

a sequence typical of a film that defies pigeonholing as erotic drama

and which very effectively demonstrates just why pink cinema demands

its status as a genre in its own right. Frog Song

is an involving, moving tale of friendship and independence

in a changing society and a fine example of why these films are so worthy of attention.

Framed

1.85:1, the picture is letterboxed rather than anamorphically

enhanced, with the English subtitles positioned outside of the picture

area. This makes zooming in on widescreen TVs a non-starter

unless your Japanese is fluent. Mine isn't, but is good

enough to spot a couple of alterations to the Japanese

original,

but for the most part they are fine. But why weren't the

lyrics to the Frog Song translated? Anyway, the picture

itself, within the confines on non-enhancement, is rather

good, with solid contrast, generally sound black levels

and a decent level of detail, although this does vary a

little in later scenes. Some compression artefacts are evident

in darker scenes, but are not seriously distracting.

The

soundtrack is Dolby 2.0 mono, but well mixed and very clear.

Silence is well used here, and is pleasingly free of even

a hint of hiss. The gentle but sparingly employed acoustic

guitar score comes across well.

Stills

7 frame grabs from the film. Nothing the pause button couldn't

give you.

Pink

Cinema Introduction

A useful textual introduction to the genre for newcomers.

Short

Film: Japanese Box (11:27)

The same short film you'll find on the Bitter

Sweet DVD with the same stills gallery.

Blood & Dishonour Book Teaser

A 5-screen gallery promo for the book in question.

Trailers

Trailers for 99 Women, Black Mass

and Venus in Furs.

Not

a disc to hunt out for its extra features, this is one that

stands on the strength of the film itself, and that's good

enough for me. Oh, and just for the the fun of it, here's

a (very) rough translation of those Frog Song lyrics:

Even

if I stick to someone's chest

I still have guts

I can't see the sky

I can't see beyond

Jump and tummy out

I'm the daughter of a frog

|