| |

"I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish." |

| |

President John F. Kennedy, 1961 |

Few things inspire the universal awe we feel toward space travel. Journeying to space has fascinated us for centuries, first explored within the pages of novels by H.G. Wells and Jules Verne, followed by further fantastic voyages on celluloid. By its very nature, depicting travel to some strange distant planet seems made for the medium of film, it allows for a filmmaker to conjure the greatest of tricks, to be grand and expressive like the vaudeville showmen of days gone by. You could show a tiny rocket ship disappearing into the eye of the moon not only because it looked amazing, new and exciting, but because no one could possibly argue with you. The possibilities are endless. It's no coincidence that one of the founding films of early cinema, Georges Méliès' La Voyage Dans la Lune/A Trip to the Moon (based on Wells' The First Men in the Moon and Jules Verne's From the Earth to the Moon) remains as beguiling to a modern audience as it does to his contemporary one, wowed by the idea of embarking on a grand tour far away from the ordinary. In Méliès' day at least, stepping foot on the moon was very much in the realm of science fiction, rather than science fact.

The powerful allure of searching for something more and the desire to find it hasn't waned, even if the frenetic days of the Space Race, which gave military men and scientists the column inches usually afforded to rockstars and celebrities have done. Even now, in our technology obsessed culture, few would balk at the chance of donning a suit and launching off into the unknown if given the opportunity. Indeed, if affluent enough, you can sign up as 'space tourist.' However, for most people, unless wealthy or one of those gifted, trained few as one of the 24 men handpicked by NASA who have the extraordinary distinction of walking on the moon, actually visiting space as if it were another country remains a fantasy, a longheld, far off wish, as distant as the moon itself, even if the logistics of exploration are now considered fact rather than fiction.

AL Reinert's For All Mankind makes that fantasy a reality, and fulfils that wish. To commemorate the twentieth anniversary of its premiere at the Sundance Film Festival in 1989, Eureka bring the film to UK DVD (and Blu-ray) for the very first time, as part of its Masters of Cinema series. Given the cultural, social and historical importance of the Apollo 11 moon landing, that propelled Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, Michael Collins and all the astronauts make contact afterward forever into the history books, it's surprising to realise that outside of the famed television footage and further excerpts released by NASA to the press or HBO's award-winning series, From the Earth to the Moon, For All Mankind stands as the only real memento to the entire Apollo Program, but it's also much more than that, and fully deserving of a place in film history on its own, considerable merit.

Though it's ostensibly a documentary, Reinert's film is no dry, tedious educative talk, this is a documentary with an intensely human perspective, since it's filmed and narrated by the men who took those legendary space walks, collecting samples, photographing and filming for the purposes of record rather than art and entertainment, preserved in the vaults of the NASA film archive, until Al Reinert came along. Then working as a journalist, Reinert lamented the fact that compared to the amount of footage the various teams of astronauts filmed the percentage seen by the public – either in newscasts or educative talks was relatively small. Rightly, he considered this something of a missed opportunity, having seen reel after reel which showcased the moon as the largest untapped natural film set, with more than enough material to make something which could show the sights previously seen by a chosen few, to a multitude.

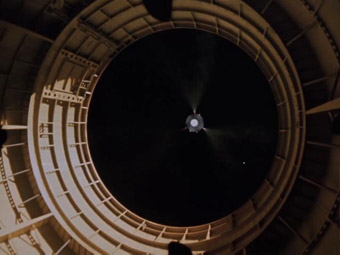

Collaborating with NASA archivists, Reinert took on the monumental task of reviewing the canisters brought back to earth, and pieced together the Apollo missions into one continuous flight. Though it might bend the rules a little in regard to the documentary form and uses a little artistic license – the striking shot of the moon in daytime, viewed from the shuttle cockpit is the only fake in the entire film – it presents the footage in a way that's entirely unique, immediately accessible to everyone, whether they have a passing or fanatical interest in the subject. One moment, we're with Alan Bean as his space suit is fitted and tested, and minutes later were with Eugene Cernan, making what would ultimately become the final footprints on the planet's surface. While that approach could be seen as dehumanising these men, by treating them as interchangeable – somewhat feeds Kubrick's theory one man in a spacesuit is much the same as another – the voiceover narration, where the men reflect on aspects of the mission, the part they played, and their feelings about the experience balances this out beautifully, changing what could have felt like a dusty, albeit beautiful artefact into something human, concrete and incredibly powerful.

In Reinert's hands, the moon is no longer a desolate, eerie place, but more a playground. The sequences which show the astronauts experimenting with the effects off weightlessness on their food, tools and bodies are a great deal of fun. Likewise, the excerpts from the various EVAs (extra-vehicular activity or space walks) are just as entertaining, especially when you recognise the famous – or perhaps infamous – banter and playfulness of the late Pete Conrad as he navigates the terrain. At the moment he falls over, we're immediately transformed into an anxious extra member of Houston's mission control.

There are few documentaries which elicit such a broad range of emotions in such a short space of time. Where this succeeds over its factually-led cousins the fact that Reinert approaches already familiar images with an artistic eye, can's once bearing the innocuous label 'Engineering Footage' – filmed, as the name suggests, for NASA engineers to see designs and equipment in situ – are breathtaking in their beauty, communicating the vastness of space and our relative miniscule stature. The clean, ethereal, serene quality that permeates common cinematic depictions of space, made famous by Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey and most recently Duncan Jones' Moon, are very much based on truth, which just makes Reinert's film even more iconic. Though somewhat of a contradiction, that ever-present iconography of a velvet black skies, brilliant, achingly white spacesuits and the pristine ashen rock of the moon itself make a place once so unfamiliar seem less so; without compromising any of its beauty.

Perhaps the most beautiful thing of all is Brian Eno's score. The phrase otherworldly is often bandied around without too much thought, but in this case, the term is, for once, correctly appropriated. In all honesty, it sounds like it's been conjured from a far off world, beamed back to us via satellite. Though the instruments which created it might be earthbound in origin, the music Eno makes with them are not. The notes have a magical, strange quality only he could have created. Outside of this haunting soundscape, further personal touches are added through the use of favourite country and pop music that the men took abroad the ship, cut with footage of them passing back and forth a tape deck, spinning through the air in zero gravity.

A vast part of the film's successfulness stems from Al Reinert and his editor Susan Korda's meticulous approach to editing the different types of source footage together in one cohesive unit. In keeping with their shaping the film as one which has more in common with a narrative rather than documentary film, sequences are often edited to reflect mood and/or pace. A particularly memorable example occurs during the countdown sequence for the rocket launch, with cuts occurring with each new number of the countdown. At the opposite end of the spectrum, the pace of the film gets dialled down several notches, when we first see the moon, and then various astronauts describe their feelings of looking back at earth from the surface of the moon. Quite rightly, it's a breathtaking moment and a future example of how well the carefully chosen excerpts of narration – culled from lengthier audio interviews conducted by Reinert – add to rather than detract from the film as a whole.

For All Mankind is a truly unique piece of cinema, combining the functions of film as record, film as entertainment and film as art, but perhaps most intriguingly of all, film as memory. The efforts of Reinert and his collaborators bring alive the true spirit of those pioneering missions, allowing us to follow in the footsteps of the brave explorers who captured those experiences on camera. Film is a medium which thrives on being a shared experience rather than a solitary pursuit and in the case of this one; the sentiment has never been truer. This is film for all citizens of the world, whether you watch this from the comfort of your armchair wishing you'd been there or sitting back and reflecting on the times when you were lucky enough to go.

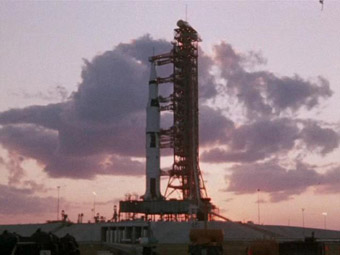

A new high definition transfer supervised and approved by producer-director Al Reinert, created from a 35mm interpositive for the US Criterion release and digitally cleaned up using MtI's DRS system and Pixel Farm's PFClean system. Digital vision's DvNR system was used for small dirt, grain, and noise reduction. Given that much of the included footage was shot on 16mm, probably high speed stock at that, the results are very impressive – the contrast is always well balanced, the detail on the best material (the rocket launch – this has to be 35mm) is excellent. The colour is a little muted in the control room sequences, but such is often the way with high speed stock, which would have been required to shoot there in available light. Grain is unsurprisingly visible here. The video material shot on the moon's surface is obviously of lower resolution, but still looks better than you're likely to have seen it previously.

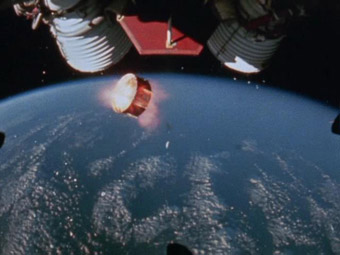

As you'd expect, the Blu-ray transfer is impressive, though not the significant leap over the DVD that you might expect. This is down in partly down to the source material, a blend of 16mm film footage and grainy monochrome video shot on the moon's surface, but also a testament to just how good the DVD transfer is – the daylight exterior tilt up on the Saturn V rocket, probably the film's most pristine image, is virtually identical on both formats. Where the different is detectable is in the command module view of the departing and approaching lunar module, which really does look gorgeous in high-def.

The Dolby 2.0 soundtrack created for the initial cinema release is clean and very clear, with the background hiss underlying radio communications very much down to how such transmissions always sounded. Frankly I'd miss it if it wasn't thyere. Brian Eno's score sounds terrific throughout, having an excellent clarity and range.

A Dolby 5.1 mix, carefully remastered and remixed from the original audio stems under the director's supervision, has been included on the Blu-ray version only and is available as either a Dolby TrueHD 5.1 or DTS HD Master Audio track. Both use the surrounds for more than just Eno's music, with the reverb from the spaceship communication as heard at Mission Control sent around the room, as is the background activity of the room itself. Both HD surround tracks have the edge over the stereo in their spread, though it's the DTS track that comes off best, having a a couple of pinches more clarity and punch than the Dolby tracks.

A port of the region one Criterion release, this is an impressive package. The care and attention take to ensure the quality of the film's transfer and audio – which is reason enough to purchase – is obvious. Beyond that, however, this release also boasts a good clutch of extra features, which will satisfy regardless of whether you're a lover of cinema, aeronautics or both.

Audio Commentary Featuring Al Reinert and Eugene A. Cernan

Recorded in 1999, with director Al Reinert and veteran astronaut Eugene Cernan, (Apollo 17 Flight Commander and the last man to set foot on the moon), this is more like an informal conversation than a classic commentary track, and highlights in very different ways, the enormity of journeying to the moon and creating a cinematic memento of it. Considering the vastly different disciplines of the two men – one a former Navy pilot and the other a film director – their conversation flows well and there's hardly any time for dead spots, thanks to the detail of their discussions. The pride, passion and respect both men feel for their work, each other and the film itself are abundantly clear. A particularly nice feature of this track is the way that Reinert and Cernan interact, and there are a few instances where Reinert turns interviewer, asking Cernan to elaborate further on his thoughts.

In all honesty, I'd feared that Cernan's comments on this track might be too technical or overanalytical given his background, but that's not the case at all. Though technical information from both sides is explored, this is tempered with some interesting notes regarding the historical context of the space program and the making of the film. Alongside this are personal anecdotes and often philosophical reflections from Cernan regarding is time as an astronaut, which gives a wonderfully human flavour to the experience as a whole. Overall, it's a great example of how tracks featuring participants with specialist knowledge can work incredibly well and be appreciated of regardless of our own understanding of the subject.

An Accidental Gift: The Making of For All Mankind (31:58)

More like small-scale documentary in its own right than your standard making-of, created to coincide with the film's twentieth anniversary (which as a whole, this release commemorates), this combines archive footage with interview excerpts to provide a detailed look at how the film came together. Contributions from Al Reinert, Alan Bean and specialist personnel, including NASA film editor Don Pickard and Morris Williams, curator of the NASA Film Archive, highlight just how much hard work – and enjoyment – was involved in the process of bringing what would ultimately become For All Mankind, to a wider audience and on a much larger screen.

The 'accidental gift' of the title refers to the fact that much of the original purpose of recording the lunar footage was purely for record sake, whether to preserve the geological make up of the planet's surface or to document procedure, with the edited down clips used for news programming or educative talks actually produced some of the most beautiful and iconic imagery ever committed to film. Artistic merits aside, he most fascinating thing to learn is just how committed NASA were in the endeavour of record, inventing technology specifically for that purpose. Though Reinert's shaping of said footage means its use it somewhat changed from its original intent, everyone involved readily acknowledges the importance of, and the need for, a lasting record of those years taken from a different perspective, which extends beyond the realms of education and science – which of course, is another kind of preservation.

Paintings from the Moon (45:26)

A selection of art work created by former astronaut and engineer, now artist Alan Bean (Apollo 12, Skylab 3), which are already famous in their own right. Like everything else here, we get plenty of details, thanks to a filmed introduction by Bean – which doubles as a mini biographical portrait – and further audio commentary as each painting is presented. These are striking and deeply personal impressions of Bean's life as an astronaut, giving a unique perspective on his experiences during those years, which nicely rounds off Bean's contributions elsewhere on the disc.

3,2,1 … Blast off! (2:24)

A short but informative compilation demonstrating the different types of rocket boosters used to launch missions. Each one is accompanied by a title card, explaining the name of the rocket in question and the different missions it was used in.

NASA Sound Archive

An interesting collection of soundbites, which encompass the Apollo Program missions. Some of these are so well-known, you'll know them before you hear them, since they're so often quoted that they've become ingrained in our collective consciousness, while others are indicative of the minutia of ensuring these legendary missions were completed without a hitch.

Booklet

This is a beautifully illustrated companion, running over twenty pages, and is a nice mix of the technical and artistic backgrounds which shaped the film's production, with a deeply personal feel, much like the film itself. Featuring NASA still photographs, this collection of essays is a real treat. For the technically minded, alongside the usual production credits and transfer information there's also an important note in regard to viewing the film in the correct aspect ratio. When viewing the film for the first time, it would be wise to follow these instructions to ensure maximum enjoyment. Though film critic Terrence Rafferty's piece, 'For All Mankind: Fantastic Voyage,'* is absent from this release, it's still very much worth reading.

The main draw for fans of the film will be the writings by director Al Reinert and film's composer, Brian Eno. Of these, 'Al Reinert on For All Mankind,' is the longest in the collection and as the title suggests, Reinert reflects on our dual fascination with space travel and capturing those expeditions on film. His second and shorter contribution, 'Backyard Wonders,' is an all-too familiar tale, describing his experience of watching the Apollo 11 crew land on the moon. Eno's essay, 'Apollo: Atmosphere's and Soundtracks' is a reprint of the liner notes for the 1983 album of the same name, the majority of which appears in For All Mankind. As a fan of Eno's music, this was a particularly nice read, detailing the origins of his collaboration with Reinert and the shape the project took, which really underlines the scale of the task undertaken by all involved, whether they be astronaut, filmmaker or composer.

For the less well-versed space nut (or if your memory is a bit rusty on names and faces), there's an optional supplementary feature, which provides on screen identification of the missions, astronauts and Houston mission control personnel as the film progresses. Since the film cuts the different missions together to create a single unified journey, this is particularly useful when enabled during a first viewing.

For All Mankind is a breathtaking fusion of history, documentary and art, which celebrates the triumph of human ingenuity. In collaboration with NASA and Brian Eno, Al Reinert has created the perfect memento of one of man's true landmark achievements: taking a trip to the moon and living to tell the tale. An essential purchase.

* Timothy Rafferty's article is available to view at http://www.criterion.com/current/posts/1197

|