|

I don't like children. I'm not looking to make enemies here or alienate readers with families, but that's the way it is. And don't try reminding me that I too was one once because I've heard it all before. It's not the result of some deeply buried trauma or a specific incident in my own past, they just irritate the hell out of me. If you have kids and love every minute you spend in their company then by all means enjoy, just keep them away from me. Please.

Now over the years I've worked intermittently as a lecturer, but almost always with adults or teenagers. I've taught young kids only once, a one-hour session with video cameras that I only agreed to do because I was told lies about the age of the pupils. I will happily admit that I was genuinely impressed at how quickly they picked up the basics, how good they were at framing shots and how fearless they were at getting in close to get that facial close-up that older students always seemed to be self-conscious about grabbing. But then I had three of the school's regular staff there to deal with behaviour issues and point the kids' heads in my direction when their attention wandered. This was not something I could or would ever want to do for a living.

But despite my feelings about these small creatures, I have genuine admiration for those that teach them and do it well, and there really are some extraordinary people working in this field. About three years ago, I was asked to make a short video about a class consisting of students with the most severe learning, communication and behavioural difficulties you can imagine, the sort of kids that a century ago would have been locked away and left to rot by a society that feared what they were not even remotely interested in trying to understand. What I witnessed humbled me. The commitment, hard work and patience demonstrated by the teachers and particularly the good woman in charge of this programme was genuinely awe-inspiring. Every lesson required hours of careful preparation and placed each member of the team at constant risk of injury from sudden and often violent outbursts. And yet they kept at it, never complained, and believed wholeheartedly in the good they were doing for these most challenged of children, despite having to persist for months to observe progress that might never actually come. Never mind those inspirational teachers of Hollywood cliché, the ones who go into tough inner city schools and turn gang-bangers into musical superstars or the like. These are the real heroes of the profession, the ones whose work goes tragically unseen and unappreciated by society at large. And yet despite everything I just said, I can't remember that teacher's name. I'll bet you real money that if I bumped into her tomorrow, despite the fact that I only spent six hours in her company, she'd remember mine.

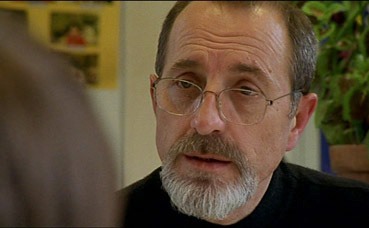

It's this very kind of teacher, the unassuming, unsung hero of the profession, that Nicholas Philibert's observational documentary Être et avoir (To Be and to Have – there has been plenty of discussion about the true meaning of that title) is constructed around. The man in question is Georges Lopez, the sole teacher at a one-room school in a remote region of rural France. At least that's what we are led to believe – a comment made by Lopez to one of the children suggests he has assistance from a woman named Tatiana, who is only seen on field trips, and even then I'm just assuming that's her.

Whatever the true staffing situation, however, we're left in no doubt that Monsieur Lopez is a teacher of considerable dedication and ability, one who is required to instruct children of various age groups and at different levels of learning. The small class sizes allow for a good deal of one-to-one interaction, a luxury for most teachers, but one that Lopez takes full advantage of with an approach whose unwavering even-handedness could at first glance be easily mistaken for dispassionate aloofness. Whether it be addressing the specific learning needs of a pupil, discussing a child's progress with a parent or moderating the aftermath of a fight, his tone rarely varies, displaying a firm but seemingly emotionless tolerance that commands respect and yet leaves him both approachable and disarmingly likeable. With little shown of Lopez's life outside the schoolroom, the only real window that is opened to the man behind this consummate and caring professional comes in the form of a brief interview, in which he outlines his feelings about his profession and how he got into it in the first place. This may temporarily disrupt the otherwise observational flow but is welcome nonetheless, and shot as it is in the peaceful solitude of the schoolhouse garden it sits surprisingly well with the scenes that surround it.

Where the film really scores, which may come as a surprise given my opening statement, is that despite the focus on Lopez, it's the kids who ultimately steal the show. While the personalities and their role in the narrative are partially the construct of editing (I would imagine there are reams of film in which the children do little to hold even the most doe-eyed adult's attention), the clips selected for inclusion are quietly priceless. These range from the girl whose construction made from pencil erasers is scuppered when one of them is nabbed from under her nose, to the antics of the irrepressible young Jojo, who has repeatedly singled out by fans of the film as its true star (it's no surprise he became the film's poster boy), with his efforts to operate a malfunctioning photocopier that is twice his height repeatedly singled out as a viewer favourite. And these kids don't have it easy on any front – as part of a remote farming community, they are also expected to put in a good few hours of work each day on the family holding, while it seems to fall to their mothers to continue their tuition outside of the schoolroom, a task that in one case amusingly expands to include just about every member of the boy's family.

Given the subject matter and the timescale covered by the film, Philibert's decision not to shoot in traditional handheld vérité style may seem surprising, opting instead for the sort of carefully framed, tripod-mounted approach more readily associated with low key drama than observational documentary. There are some shots where the camera is positioned so close to his subject (the long sequence in which Lopez questions Julien and Olivier about their fighting has a perspective that places the camera only a few feet from the boys themselves) that a suspicious mind could easily suspect that elements have been staged for the camera and that this is why the children seem largely oblivious to its presence. But having filmed and photographed children myself on more than one occasion (yeah, I know, why me of all people?), one thing I have learned is that while kids are initially fascinated by any new such presence in their everyday environment, they soon become used to it and will eventually ignore it and return to whatever it is that usually preoccupies them. And frankly, if you spend a year intermittently filming the same group, then sooner or later any filmmaker worth their salt is going to develop an eye for when and where the interesting material will occur, and Philibert certainly has that.

What the film does share with classic vérité and direct cinema is that it lets its subject speak for itself, with no assistance from introductory or mid-film captions or explanatory voice-over. The narrative development is slight but quietly significant, as Jojo's early problem with numbers is later shown to be impressively conquered, and Julien and Oliver put their confrontational past behind them as they prepare to move up to middle school and Lopez tells the self-confident Julien that he expects him to look out for his quieter friend.

For Lopez himself, the year is a conclusive one, his last as a teacher at a school he has served for twenty years and a profession that he has worked in for thirty-five. It's this that provides the film with its low-key equivalent of emotional climax, as the students talk of going on strike to get him to stay and one is reduced to tears at the prospect of his departure. Lopez's own emotions about this significant event are held largely in check, but flicker movingly to the surface as he says goodbye to the children for the last time – the lingering look on his face and his faltering composure as he stands at the classroom door and watches them depart speaks volumes about his commitment to both his job and the children in his charge.

Watching the film again six years on from its first UK cinema and DVD release in this somewhat belated coverage of its DVD re-issue from Artificial Eye (the original release was handled by the now departed Tartan) was an experience inevitably touched by knowledge of subsequent events. As many may be aware, the film's success at festivals and the box-office led to Lopez suing the filmmakers for a larger fee than was initially agreed, a claim for compensation that was rejected by the court. The reaction to this has been interesting, with disappointment being the most commonly expressed emotion, not because Lopez did not deserve to share in the film's financial success (he did, after all, participate in a number of promotional tours and screenings in support of the film) but because the action itself seemed to sit uncomfortably with the idealistic figure the film had crafted him into, and as we all know idealists do what they do for love and not money. It is possible to appreciate both sides of the argument here. Lopez was likely never paid a great deal for his teaching work and received only a nominal fee for his participation in the film, and it must have been a little galling to enter retirement armed only with what savings he may have acrued and whatever pension has been provided for him while others ride a wave of success on the back of his years of hard work. But for the filmmakers, the acclaim and financial rewards, such as they were (this is a small French documentary, after all, not Transformers), represented their payback for a year of dedicated work and offered them a small financial cushion for the time and effort they would presumably be investing in their next project. Frankly, we'll probably never know the full details of the exchanges that ultimately led to this action, and the hope is that knowledge of the falling out does not lead to a re-reading of the film, one that in any way tarnishes the dedication and work of either Lopez or Philibert. Both are doing their jobs, after all, but with a skill and dedication that remains, I believe, beyond question.

Shot on 16mm, evident in the sometimes very visible (though never coarse) film grain, the picture is otherwise very good, with solid reproduction of prime colours and reasonable flesh tones, not easy given that much of it was shot in classrooms under a mixture of daylight and artificial light, always a troublesome combination for film. The contrast is also pleasing, with only slight loss of shadow detail in some sequences, and there's a richness to much of the imagery that I still regard as specific to film and that HD has still never quite captured. The framing is 1.66:1 and the picture is anamorphically enhanced.

The sound is Dolby 2.0 stereo only, but the clarity and range are excellent, particularly in the bass rumble of wind and vehicle motors and the was-that-in-the-room? precision of dripping water.

It's a Tartan re-issue, sure, but a perfect opportunity to add some new supplementary material and make it worth the upgrade for those who have the original, but Artificial Eye have passed. All we have here is a Nicholas Philibert Filmography, which has not been updated to include the 2007 Retour en Normandie, and the Original Theatrical Trailer (1:39).

Six years on and Être et avoir has lost none of its beguiling charm, and denied the full details of the post-release law suit it really is worth putting subsequent events aside to appreciate both the film and Monsieur Lopez on their own considerable merits. In picking up the title from Tartan's ashes, Artificial Eye have made sure the film remains available on UK DVD – it's just a shame they didn't take the opportunity to expand the supplementary material and make it feel more like a new release than a re-issue.

|